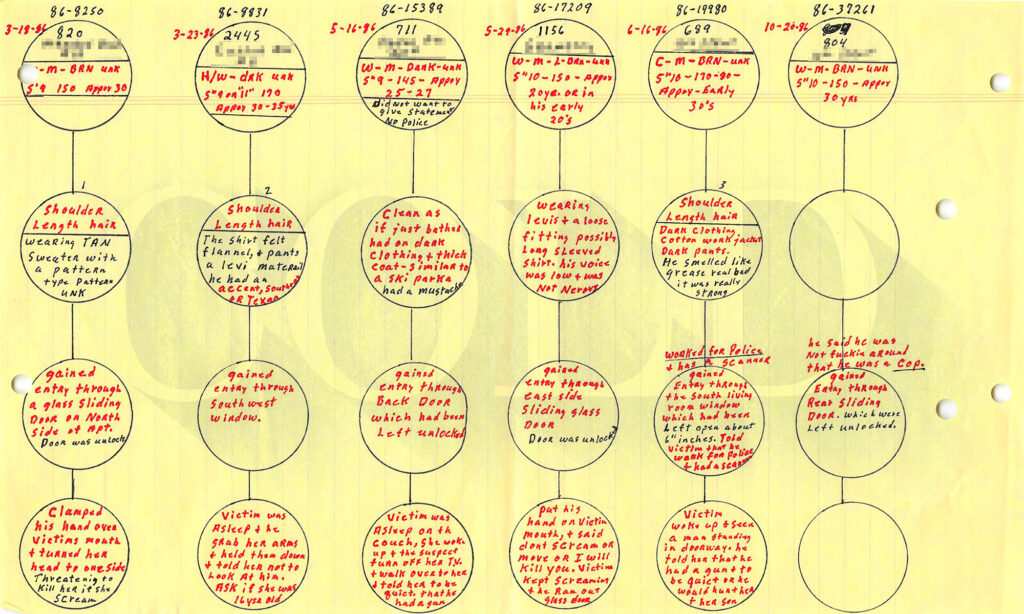

Police in Ogden, Utah spent the mid-1980s searching for a man detectives dubbed the Ogden City Rapist. They identified more than 12 cases from 1984, 1985 and 1986 in which a man sexually assaulted or attempted to assault women in their own homes.

The cases bore commonalities that led investigators to believe one man might be responsible for most or all of the crimes: he targeted divorced or single women with children, he entered through unlocked windows or doors, threatened the lives of the women’s children and sometimes mentioned police department connections.

Tips eventually led police to a suspect toward the end of 1986. He was a former member of their own department’s volunteer reserve corps, a man named Cary Hartmann.

The Ogden City Rapist investigation

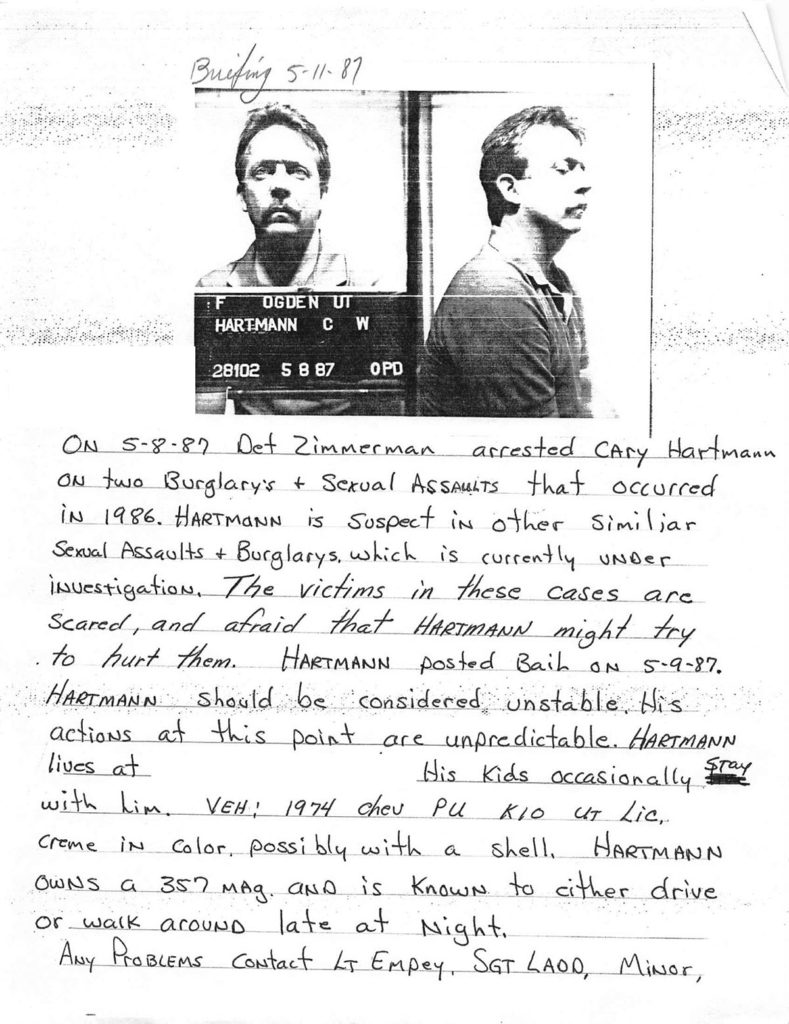

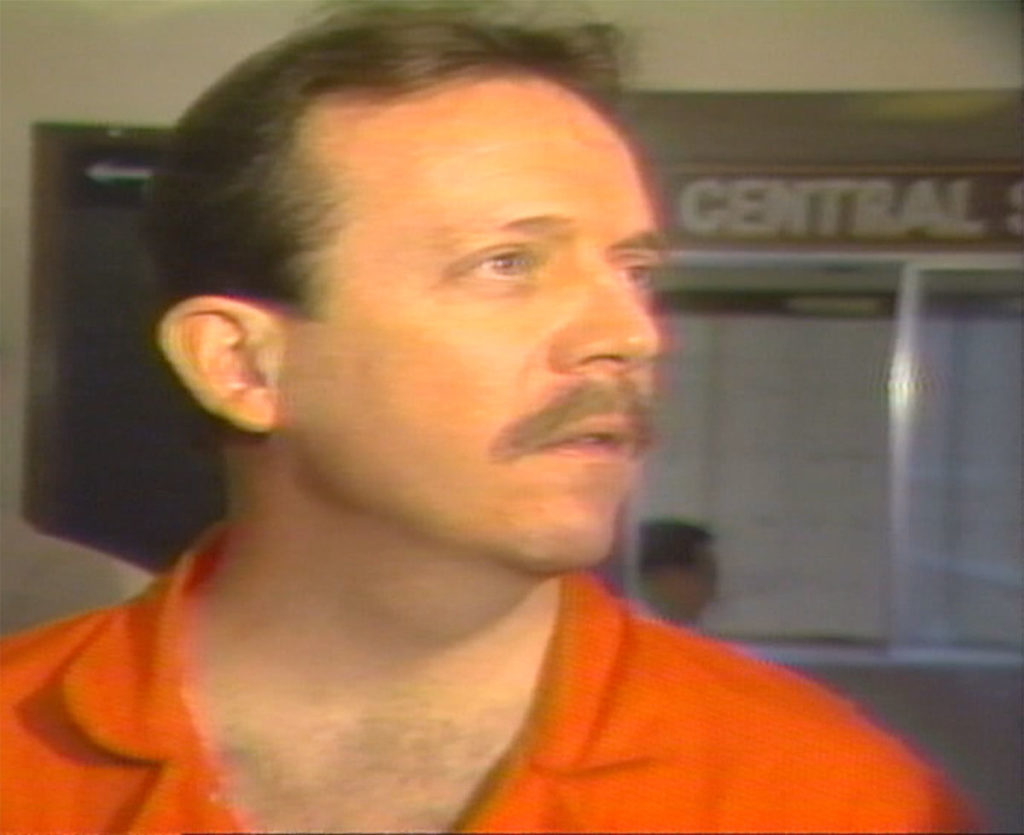

Ogden police arrested Cary Hartmann on suspicion of rape on May 8, 1987. Cary’s mugshot from the Weber County Jail showed at the time of his arrest he had dark brown hair and a thick mustache.

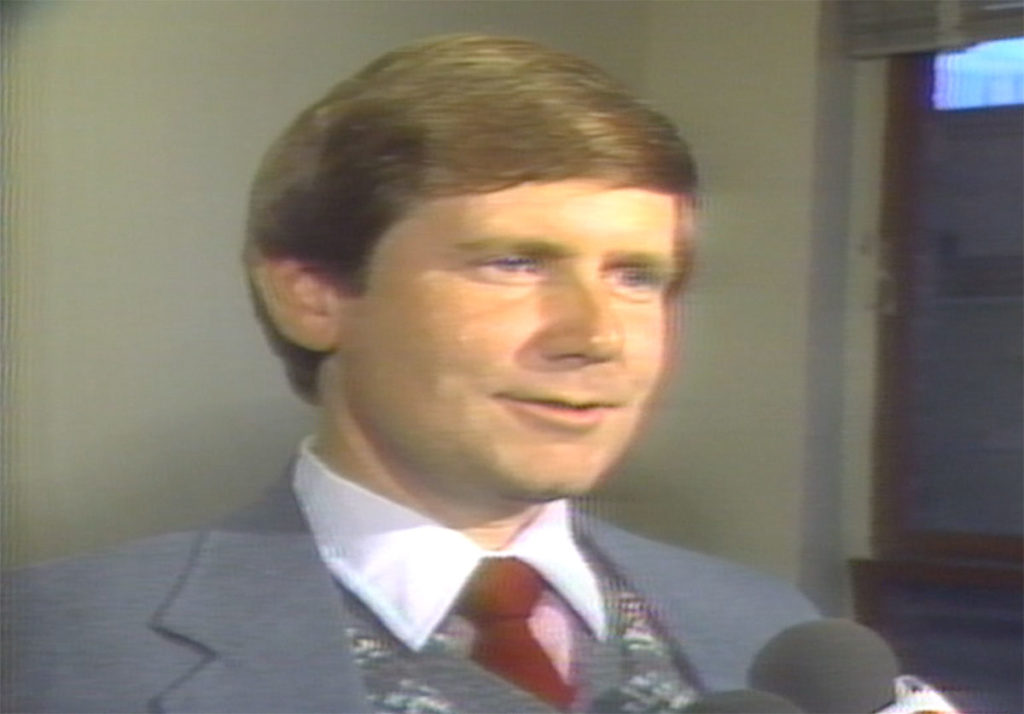

News coverage of Cary’s arrest generated a flood of new leads for the investigators. One of them, former Ogden police detective Shane Minor, spoke to COLD about his role in the case.

“I took a couple of date rape-type of phone calls, where people called in, said they’d gone out with [Cary] and it’d gone a little too far but they were too embarrassed to come forward or call it in [at the time],” Shane said.

Weber County prosecutors subsequently filed criminal charges against Cary in connection with four separate sexual assaults dating from March, May, June and October of 1986. In each case, investigators believed they could link Cary to the victims through statements he’d made following his arrest, as well as physical evidence.

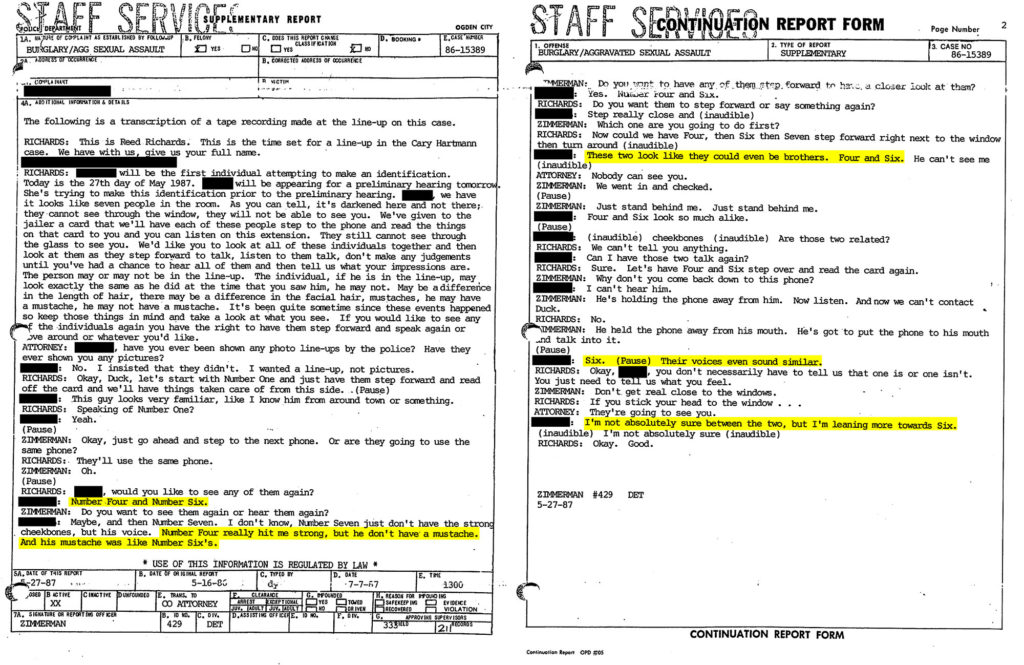

One of the four women told prosecutors she wanted to try and identify her attacker from a line-up. Police records from the Ogden City Rapist investigation obtained by COLD show the line-up took place on May 27, 1987.

Cary, through his defense attorney, arranged to have his brother, Jack Hartmann, and cousin, David Hartmann, standing in the line-up with him. He’d also shaved his mustache and lightened his hair prior to the line-up. A transcript of the line-up showed the woman wavered between identifying Cary or David Hartmann as her attacker. David Hartmann bore a strong resemblance to his cousin Cary.

In personal notes Cary made regarding the line-up later that same day, Cary wrote David Hartmann “saved our buns.”

Cary Hartmann’s trial in the Ogden City Rapist case

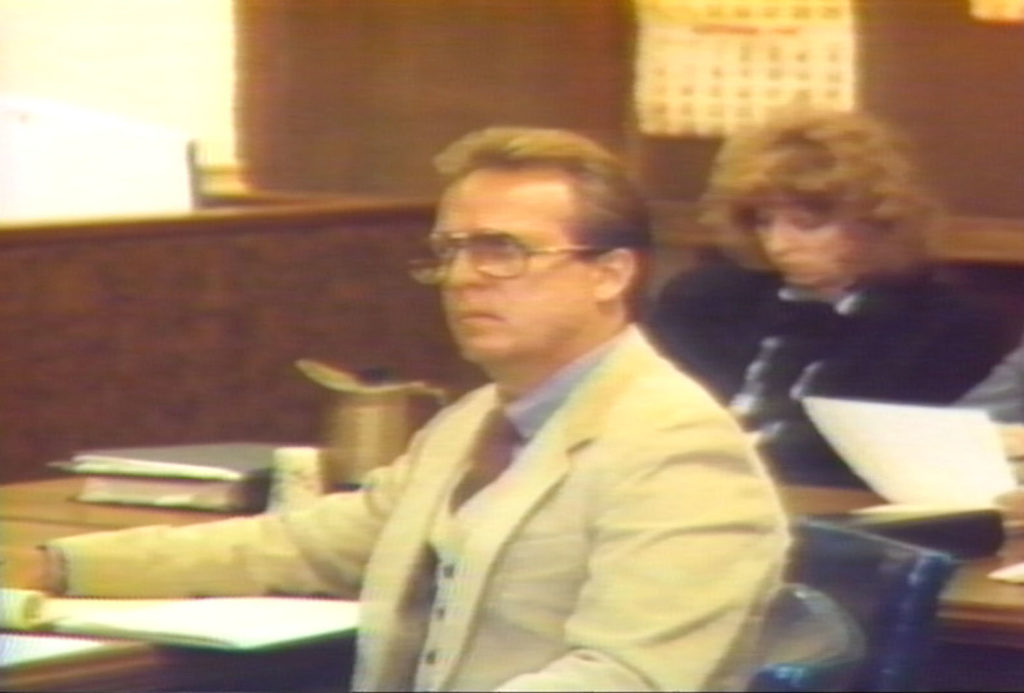

Cary stood trial on the first of the sexual assault cases in September of 1987. The woman who’d attempted to pick her attacker out from the line-up testified, expressing anger at having been “set up.”

Cary took the witness stand in his own defense days later. He denied having ever seen the woman and said he’d never raped anyone. Cary’s defense portrayed him as a man falsely accused of being a serial predator, of being the Ogden City Rapist.

A prosecutor asked Cary why he’d shaved his mustache prior to the line-up. Cary said he’d felt disgusted by conditions inside the Weber County Jail and wanted “to be clean” after posting bail, according to a Sept. 19, 1987 story in The Salt Lake Tribune.

The jury returned guilty verdicts against Cary Hartmann on counts of aggravated sexual assault and burglary on Sept. 22, 1987. The judge ordered the preparation of a pre-sentence report. An investigator with Utah Adult Probation and Parole spent three weeks compiling the report. It concluded with a recommendation that the judge impose a maximum sentence.

“The defendant is very intelligent and cunning and because of this is probably more dangerous than if he were not so astute,” investigator Kendell Phillips wrote.

Utah 2nd District Court Judge David Roth heeded that advice. On November 2, 1987, Roth sentenced Cary Hartmann to two terms of 15-years-to-life, as well as one term of 5-years-to-life, in the Utah State Prison.

Searching for Sheree Warren’s body

Weber County Attorney Reed Richards had convinced a jury beyond a reasonable doubt that Cary Hartmann committed the crime of sexual assault. But he’d declined to charge Cary with a crime related to Sheree Warren’s disappearance.

“He was a rapist,” Reed said, “he was not, as far as we knew, a killer.”

Reed didn’t believe the case was strong enough in the absence of direct physical evidence. Most critically, police had failed to locate Sheree Warren’s body, or to uncover any other proof she was dead.

“If you charge a case like that and you can get through the preliminary hearing, where you’ve got to show probable cause, then you’re ending up with a trial,” Reed said during an interview for COLD. “If you go to trial and don’t get a conviction, you’re all done. You’ve got double jeopardy that steps in and even if you get perfect proof later on, you’re dead.”

But Cary Hartmann’s sentence in the sexual assault case carried what’s known as a “minimum mandatory.” It meant Cary had to serve at least 15 years before he could possibly qualify for parole. Reed, the prosecutor, believed that gave investigators looking into Sheree Warren’s presumed death the advantage of time.

“So the decision was made ‘let’s keep investigating it’ and ‘he’s not going anywhere, let’s see if we can find some additional information, maybe we can find the body,’” Reed said.

Silence about Sheree Warren

Cary Hartmann began serving his sentence on November 3, 1987. He immediately requested a transfer out of the Utah State Prison, stating his status as a former reserve officer for the Ogden Police Department made remaining at the prison a threat to his safety. A warden agreed and moved Cary to the Sanpete County Jail in Manti, Utah.

At the beginning of February, 1988, Cary accepted a deal that resolved three additional sexual assault cases. He pleaded guilty to an amended charge of rape in one of those four cases. In exchange, prosecutors dismissed charges from the remaining two cases.

Weeks later, Ogden police detectives Chris Zimmerman and Shane Minor made an unannounced trip to the Sanpete County Jail with the intent of interviewing Cary about Sheree Warren’s disappearance.

“We thought we’d give it a try,” Shane said. “He wouldn’t talk to us. Walked in the room, seen we were sitting there, turned around and walked out.”

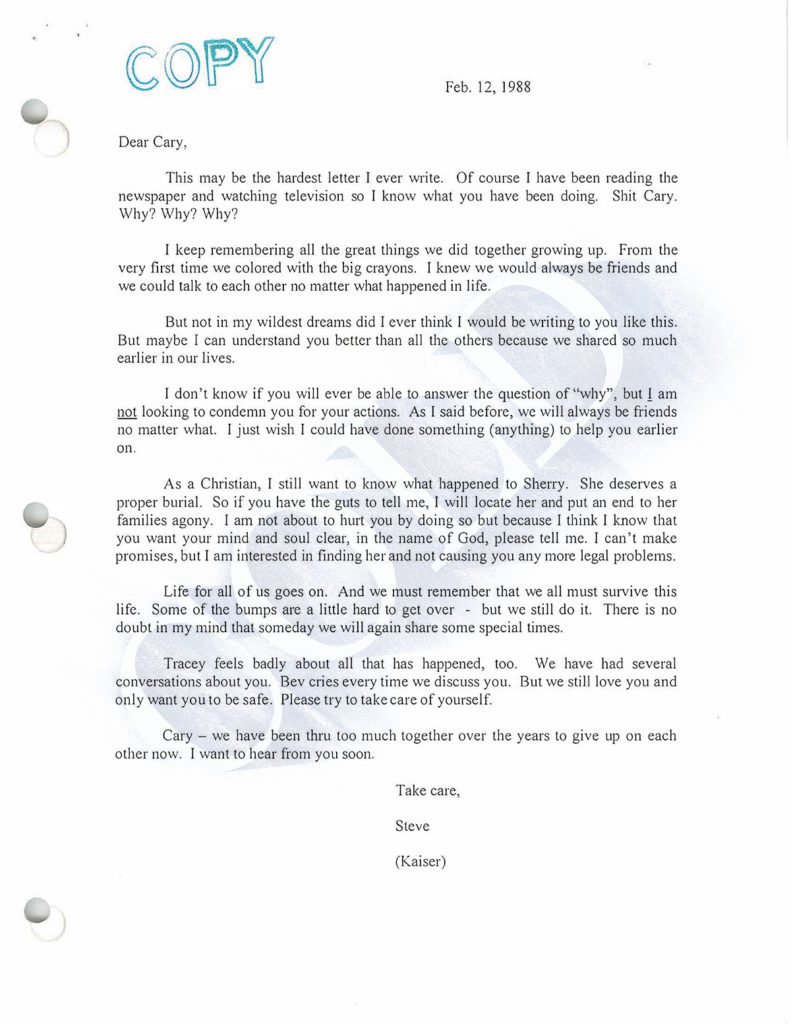

A letter from an old friend

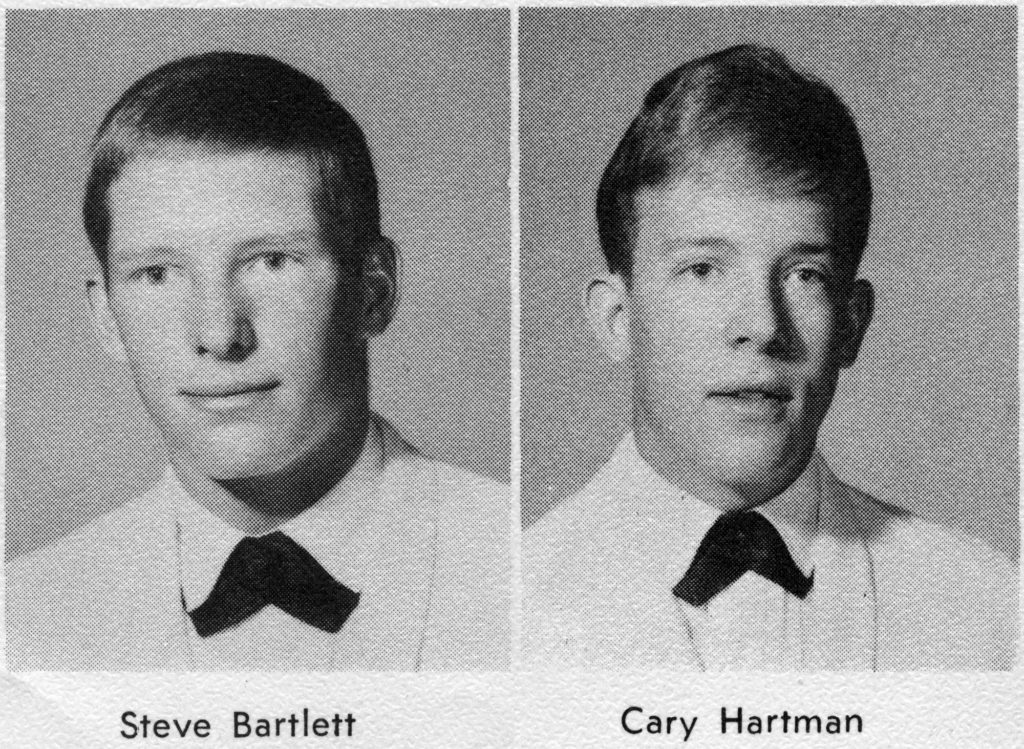

One of Cary’s close friends wrote him a letter during this same period. Steven “Kaiser” Bartlett had grown up with Cary in Uintah, Utah. They’d attended Bonneville High School together and remained close into adulthood.

“From the very first time we colored with the big crayons, I knew we would always be friends and we could talk to each other no matter what happened in life,” Bartlett wrote in a letter to Cary dated February 12, 1988.

Steve Bartlett had pursued a career in law enforcement, as both a deputy for the Salt Lake County Sheriff’s Office and an investigator for the Salt Lake County District Attorney’s Office. He wrote that he struggled to understand why Cary had committed the crimes.

Cary had enlisted Bartlett’s help in trying to find Sheree Warren in the first days and weeks following her disappearance. But in this letter a little over two years later, Bartlett suggested he’d come to believe Cary was responsible for Sheree’s presumed death. He asked Cary to confess.

“I can’t make promises, but I am interested in finding her and not causing you any more legal problems,” Bartlett wrote.

In a reply letter dated March 23, 1987, Cary denied responsibility for the sexual assaults. He said he had not been picked out of a line-up, failing to acknowledge how he’d altered his appearance and stacked the line-up with two relatives. Cary also told Bartlett he did not know what’d happened to Sheree.

“I did not do any of these things,” Cary wrote. “I forgive you, your insecurities toward me.”

Steve Bartlett’s emotional appeal

Steve Bartlett sent Cary a second letter on April 17, 1988. In it, Bartlett brushed aside his old friend Cary’s denials.

“As the jury deliberated, I felt sorry about the whole situation,” Bartlett wrote, in reference to Cary’s sexual assault trial six months prior. “My heart was on your side but my mind said otherwise. My head could not overcome the evidence.”

Bartlett also said he still believed Cary was withholding information about Sheree Warren.

“Maybe she deserved whatever she got but I am certain you are not telling me everything you know about what happened to her or where she is now,” Bartlett wrote. “Friends don’t lie to friends, remember?”

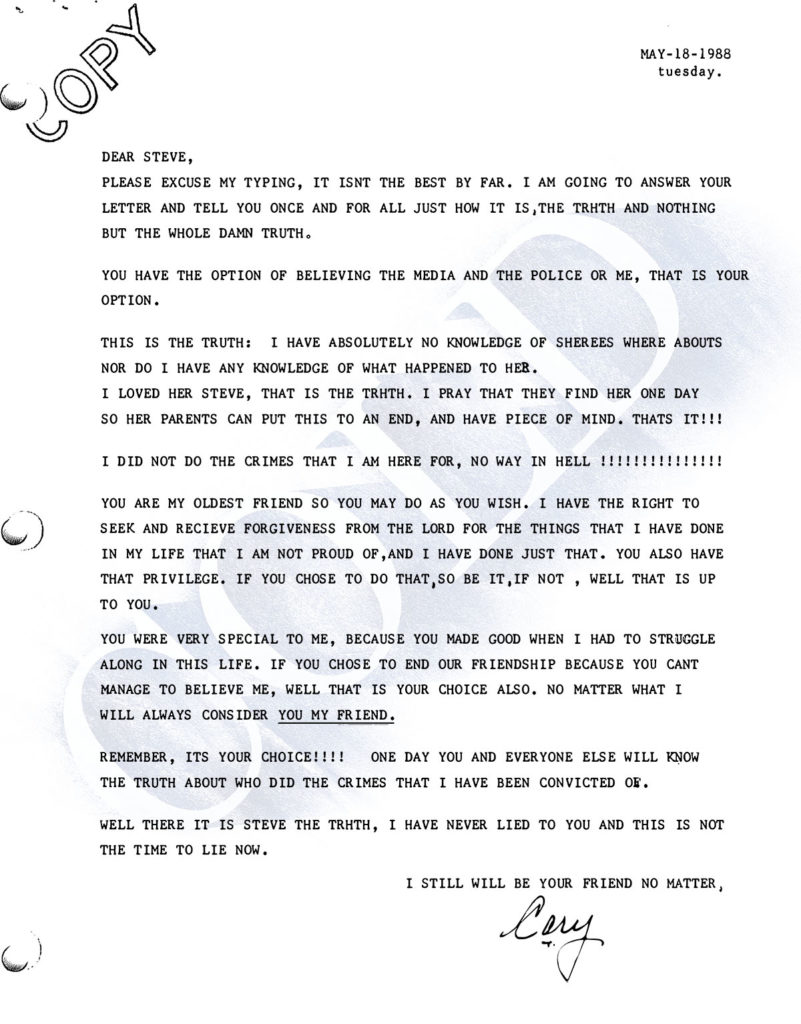

Cary, in a reply dated May 18, 1988, again insisted he had no knowledge of Sheree Warren’s fate.

“I loved her Steve, that is the truth,” Cary wrote.

Hear what happened when Sheree Warren’s family held a memorial in her memory in Cold season 3, episode 5: Nighthawk

Episode credits

Research, writing and hosting: Dave Cawley

Audio production: Aaron Mason

Audio mixing: Ben Kuebrich

Cold main score composition: Michael Bahnmiller

Additional scoring: Allison Leyton-Brown

KSL executive producer: Sheryl Worsley

Workhouse Media executive producers: Paul Anderson, Nick Panella, Andrew Greenwood

Amazon Music and Wondery team: Morgan Jones, Candace Manriquez Wrenn, Clare Chambers, Lizzie Bassett, Kale Bittner, Alison Ver Meulen

KSL companion story: https://ksltv.com/529482/cold-podcast-witness-undermines-alibi-in-sheree-warren-cold-case/

Episode transcript: https://thecoldpodcast.com/season-3-transcript/nighthawk-full-transcript/