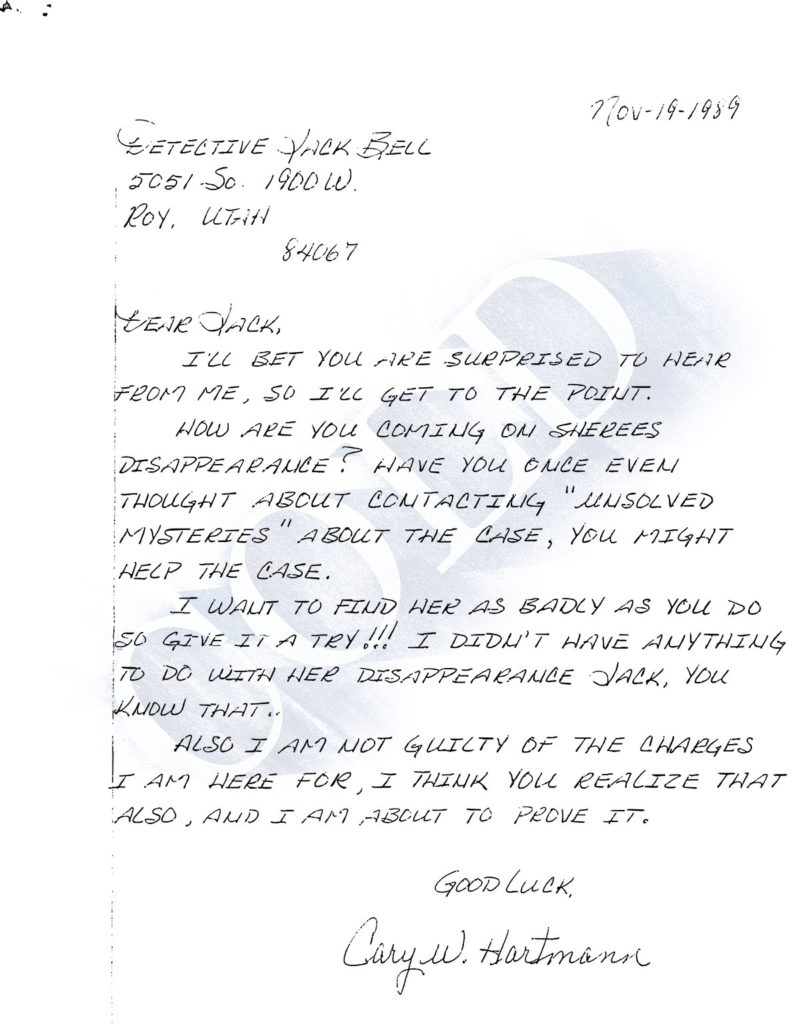

Sheree Warren had been missing just over four years when her former boyfriend, Cary Hartmann, reached out to an old acquaintance. Cary wrote a letter to Jack Bell, the Roy City police detective who led the initial investigation into Sheree’s disappearance.

“Dear Jack, I’ll bet you are surprised to hear from me,” Cary wrote. “How are you coming on Sheree’s disappearance?”

Cary was at the time housed at the Iron County Correctional Facility in Cedar City, Utah. He was serving a pair of 15-year-to-life sentences for his convictions on two aggravated sexual assault charges unrelated to Sheree Warren’s case.

“I didn’t have anything to do with her disappearance Jack, you know that,” Cary wrote.

The letter, dated November 19, 1989, arrived in Jack Bell’s inbox just days after the popular TV series Unsolved Mysteries aired an episode about a different Utah cold case.

“Have you once even thought about contacting ‘Unsolved Mysteries’ about the case,” Cary wrote. “I want to find her as badly as you do so give it a try!”

Unsolved Mysteries

NBC aired an episode of Unsolved Mysteries on November 1, 1989, that described a rape and murder in Arlington County, Virginia. In that segment, investigators described gathering blood samples from potential suspects to compare against forensic evidence gathered from the victim’s body.

A week later, Unsolved Mysteries featured a Utah cold case: the unsolved murder of Rachael Runyan. Three-year-old Runyan had been abducted from a playground adjacent to her family’s home in August of 1982. Her body was discovered weeks later, along a creek in rural Morgan County, Utah.

Cary Hartmann had been serving in the Ogden Police Department’s reserve corps at the time of Runyan’s abduction and would likely have been aware of the high-profile case.

It’s not clear whether Cary watched either of these specific Unsolved Mysteries segments. His letter to Jack Bell did not mention Rachael Runyan by name or discuss the emerging science of DNA forensics. But Cary’s mention of Unsolved Mysteries was followed by a cryptic pledge.

“I am not guilty of the charges I am here for,” Cary wrote. “I think you realize that also, and I am about to prove it.”

The Sheree Warren case changes hands

Jack Bell had come to believe Cary Hartmann manipulated him during the early stages of the Sheree Warren investigation. They’d been acquainted in high school. Jack suspected Cary had leaned on that familiarity to steer Jack toward a suspect: Sheree Warren’s estranged husband, Charles Warren.

“I missed quite a bit to start with because Cary wanted me to miss that and go after [Charles],” Jack said.

But Jack’s focus had shifted away from Charles Warren in 1987, following Cary Hartmann’s arrest in the Ogden City Rapist investigation. Jack at that time gathered information from two witnesses who’d been living above Cary in a house on Ogden’s 7th Street at the time of Sheree Warren’s disappearance. They’d described overhearing a loud argument between Cary and Sheree at the house on or around the night Sheree disappeared.

If the accounts of the two witnesses were accurate, it would mean jurisdiction over Sheree’s case should fall to the Ogden Police Department.

As a result, Jack had handed the Sheree Warren case to Ogden police in 1987. Jack was no longer in charge of Sheree’s case by the time he received Cary’s letter at the end of 1989. He paid the letter little mind.

“That’s what the letter meant to me: more manipulation,” Jack said.

Cary Hartmann DNA evidence

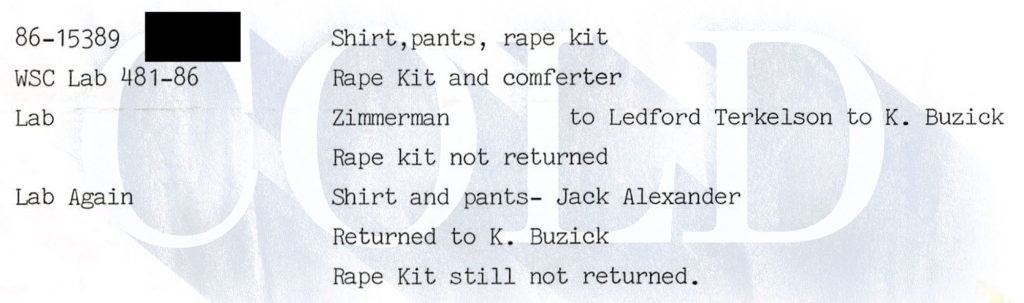

Days after sending the letter to Jack Bell, Cary Hartmann filed a civil lawsuit. It targeted James Gaskill, the director of the crime lab at Weber State College.

The prosecution in Cary’s trial had relied on serology, the study of bodily fluids, to make the argument Cary was the person responsible. DNA forensics were not at that time established as a reliable form of evidence in Utah’s criminal courts. Serology allowed investigators to narrow down a pool of suspects based on their blood types.

Weber State College’s crime lab had analyzed vaginal swabs from the victim. They indicated the presence of bodily fluids from a person with type-O blood, as well as a second person with type-B blood. The victim in the case had type-O blood.

“We didn’t have DNA back then,” former Weber County Attorney Reed Richards told COLD. “Now we might’ve approached it a little differently.”

Cary had provided the crime lab with blood and semen samples. Testing revealed Cary had B-type blood. His semen sample did not contain any sperm cells. Cary had undergone a vasectomy in 1979, years before the rape of which he stood accused.

Microscopic examination at the crime lab had revealed the presence of “a few” sperm cells in vaginal smears gathered from the body of the victim. At trial, Cary’s defense argued those sperm cells ruled him out as a suspect.

Court battle over blood types

The prosecution disagreed. The state presented testimony that the victim had been sexually active with another man in the days prior to her assault. The sperm cells, prosecutors said, had likely come from that other man.

The prosecutor, Reed Richards, also told the jury serology wasn’t the only evidence pointing to Cary as the person responsible. Cary had made comments to Ogden police detective Chris Zimmerman prior to his arrest about entering the woman’s home.

The victim also identified Cary as the man who’d attacked her from the witness stand.

The jury concluded proof beyond a reasonable doubt existed to show Cary Hartmann had committed the crime. It found him guilty.

Cary Hartmann DNA lawsuit

Cary’s lawsuit aimed to overturn his conviction. It demanded the release of the forensic evidence gathered from the body of the victim. Cary intended to have DNA analysis performed, in an effort to establish his innocence.

Weber County Attorney Reed Richards did not oppose the request for Cary Hartmann DNA analysis. But Richards didn’t want the state to bear responsibility for the expense.

“I had no problem with any DNA samples,” Richards said. “Problem is, I doubt that they save that stuff.”

In December of 1990, a judge ordered Weber State College crime lab director James Gaskill to turn the forensic evidence swabs over to a 3rd party lab for the purpose of DNA analysis.

Gaskill attempted to locate the items, only to discover they were not in storage. The crime lab did not have any record of the swabs being destroyed. Ogden police had no record they’d been returned to their department.

Gaskill told the Associated Press in September of 1991 the evidence had been lost. But the crime lab director also said he didn’t believe DNA analysis of the swabs would’ve benefited Cary.

“The likelihood of anything valuable coming from it is very, very low because Cary Hartmann doesn’t have any sperm cells, and that’s where you get DNA from,” Gaskill told the AP.

A letter to President Bush about the Cary Hartmann DNA

Cary had asked the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole to delay his initial hearing while the effort to obtain DNA analysis was pending. With the lawsuit resolved, the board scheduled the hearing for January 17, 1992.

As that date approached, Cary wrote another letter. He addressed this one to The White House and President George H. W. Bush.

“I am going to enclose a packet of documents that will explain to you my efforts in pursuing DNA testing to prove my innocence,” Cary wrote. “Isn’t this a coincidence, that as I am about to prove my innocence unequivocally, the crime lab lost the evidence.”

Cary’s request for DNA analysis, he argued, was itself proof of his innocence.

“Why would I go to all of the trouble of having this testing done; with great expense, with the tremendous amount of the effort involved,” Cary wrote, “just to have the results come back saying that he is guiltier!?!”

The letter concluded with a request for President Bush to personally intervene on Cary’s behalf, by contacting the parole board.

“I am an innocent man in prison, and I need help,” Cary wrote.

The Cary Hartmann DNA letter to President George H. W. Bush made no mention of Sheree Warren, or the fact Cary remained a suspect in Sheree’s disappearance. The White House did not take up Cary’s cause. No one from the Bush Administration came to Cary’s aid when he made his initial appearance before the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole.

But the issue of Cary Hartmann’s DNA did arise during that hearing on January 17, 1992. A parole board member listened as Cary complained about how the crime lab had lost the DNA evidence. She told Cary he made a “passionate” and “persuasive” argument, but the parole board didn’t hold the power to overturn his conviction.

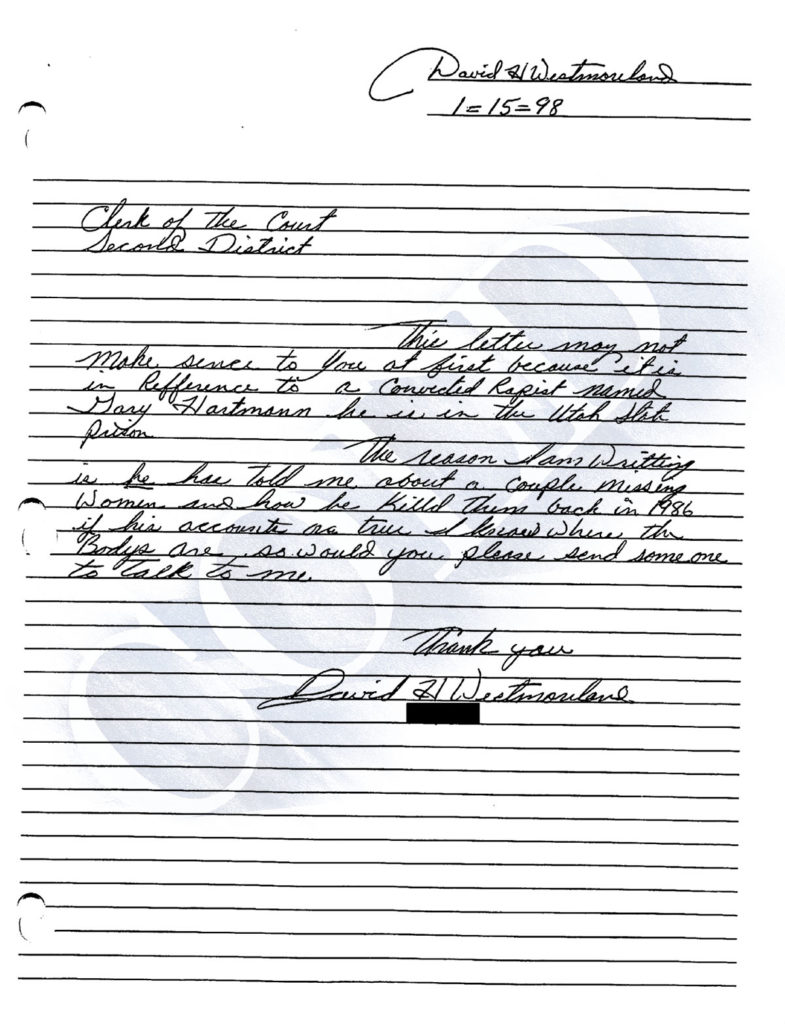

An informant shares a location for Sheree Warren

Years would pass before Jack Bell, who’d first investigated Sheree Warren’s disappearance, received another letter. This one didn’t deal with Cary Hartmann DNA, or Cary’s protests of innocence. It instead involved a claim of Cary’s guilt of another suspected crime: the death of Sheree Warren.

The letter came from a convicted murderer named David Westmoreland, who’d lived in a cell next to Cary’s at the Iron County Correctional Facility.

Westmoreland had a violent past. He’d beaten and stabbed his own cousin, Maxine Westmoreland, to death in May of 1981 after discovering she was an informant in a drug investigation. Westmoreland fled to Texas after the killing but was arrested and extradited to Utah. He then pleaded guilty to a murder charge and received a sentence of five years to life in prison.

In 1986, David Westmoreland said he was the legendary hijacker D.B. Cooper, a claim investigated and ultimately discounted by the FBI.

So Westmoreland’s credibility was already suspect when he wrote a letter in 1998 stating he had evidence about not one but two murders allegedly carried out by Cary Hartmann.

Jack Bell was by that time a captain with the Roy City Police Department. He traveled to Cedar City to interview Westmoreland on April 16, 1998. Bell’s notes, obtained by COLD, said Westmoreland claimed Cary had confided he’d killed someone. Cary allegedly told Westmoreland “he had not been charged with the murder because the dumb cops could not find the body.”

The Echo Canyon rest area

Westmoreland told Jack the body was buried near a rest area alongside I-80 in Echo Canyon. The gravesite was supposedly “next to a flower garden behind the rest area.” Westmoreland said he’d been there himself once. He described “restrooms with a paved walkway to an overlook that looked down to a small meadow of wildflowers about 200 yards away.”

Bell went to the rest area following his interview with David Westmoreland. From the paved walkway, Bell looked across the interstate and saw orange cliffs on the far side of the canyon.

The view reminded Bell of a conversation he’d had with Cary Hartmann back in October of 1985, shortly after Sheree Warren disappeared. Cary had described a coworker having a dream about Sheree’s death. The dream involved a truck stop in the mountain and red rock cliffs. Bell believed the view from the rest area matched the description of the truck stop in the mountains Cary had provided.

“So boom,” Jack said. “That’s what I got out of what Cary supposedly told Westmoreland: where she was at was up there.”

Hear what happened when police searched for Sheree at the Echo Canyon rest area in Cold season 3, episode 6: Lying Liars

Episode credits

Research, writing and hosting: Dave Cawley

Audio production: Adam Mason

Audio mixing: Ben Kuebrich

Cold main score composition: Michael Bahnmiller

Additional scoring: Allison Leyton-Brown

KSL executive producer: Sheryl Worsley

Workhouse Media executive producers: Paul Anderson, Nick Panella, Andrew Greenwood

Amazon Music and Wondery team: Morgan Jones, Candace Manriquez Wrenn, Clare Chambers, Lizzie Bassett, Kale Bittner, Alison Ver Meulen

Episode transcript: https://thecoldpodcast.com/season-3-transcript/lying-liars-full-transcript/