Kim Salazar: His decision that night in April of ’85 altered my life forever.

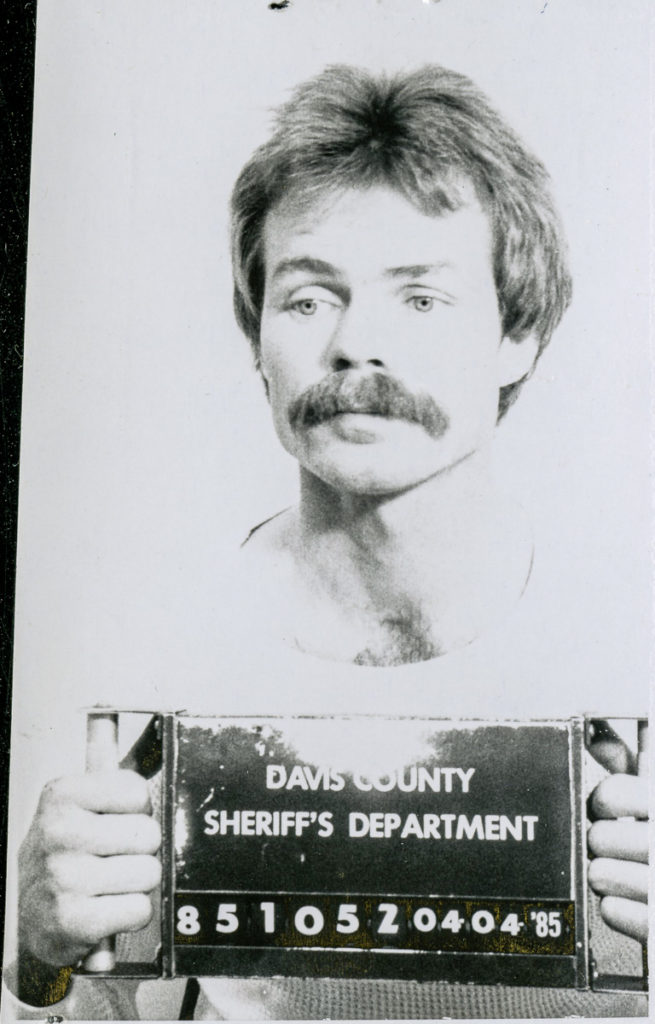

Dave Cawley: Joyce Yost’s daughter, Kim Salazar, was not satisfied. Doug Lovell, the man convicted of kidnapping and sexually assaulting her mother, was headed for sentencing. But not for Joyce’s murder.

Randy Salazar: She told the detectives, I remember her telling them, ‘I know that son of a bitch has something to do with it. I know he has something to do with it.’ And they told Kim, ‘We’re sure he is too but we just can’t, I mean, we can’t just go over there and tell him he has something to do with it. We have to figure something out here.’

Dave Cawley: Two years earlier, the Utah Legislature had established a system of minimum mandatory sentences.

Brian Namba: The reason we call it mandatory is the judge, if you got the conviction, the judge could not give him probation.

Dave Cawley: That’s retired Davis County prosecutor Brian Namba. Under the law, Judge Rodney Page had to send Doug to prison for at least 10 years. Unless there were mitigating circumstances, in which case Doug would get no less than five. Or, if there were aggravating circumstances, he’d get no less than 15. Brian had filed a motion arguing in favor of the longer, 15-year term.

Brian Namba: So there’s a list of potential aggravating circumstances.

Dave Cawley: They included Doug’s pattern of stalking women, the extreme cruelty and depravity of his attack on Joyce, his history of violent offenses, his pending charges for car theft and his hostility toward Joyce’s family.

Brian also pointed out it was only because of Joyce’s hesitancy to testify about specific sexual acts during the preliminary hearing that the sodomy charge had been dropped.

Doug’s attorney, John Hutchison, didn’t file a motion of his own full of mitigating circumstances. Instead, he simply asked Judge Page to treat Doug’s convictions as misdemeanors, which would spare him prison time altogether. Hutchison argued it would be “unduly harsh” to send Doug away for so long, because of “the nature and circumstances of the offense and the defendant’s history and character.”

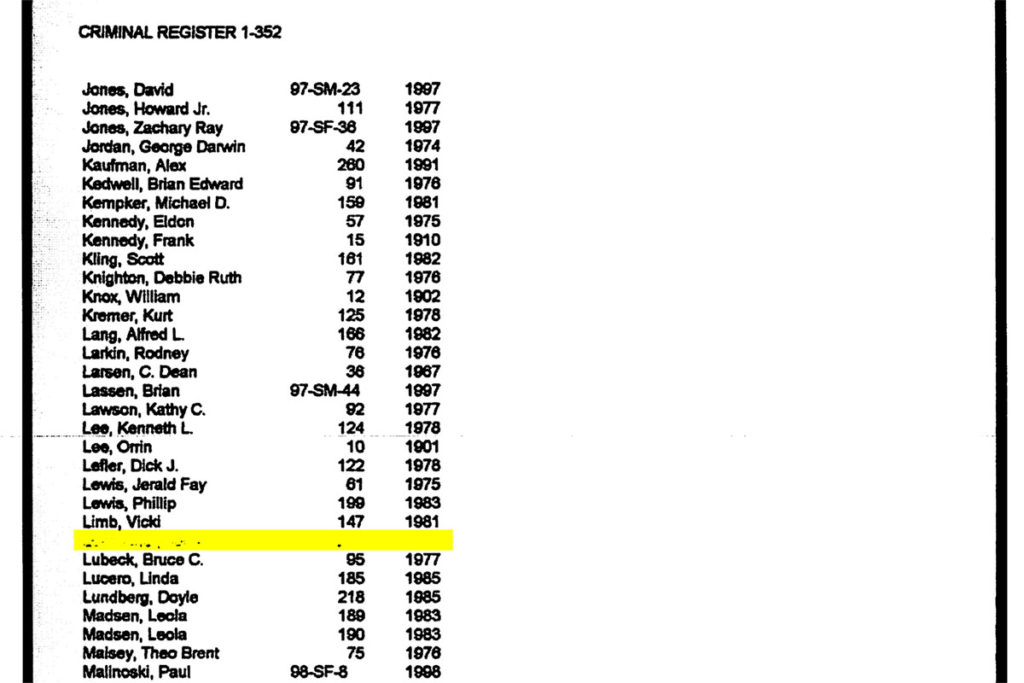

Judge Page reviewed a confidential pre-sentence report prepared by an agency called Adult Probation and Parole — or AP&P. It included background information on Doug, his family relationships, his criminal history, as well as the impact of his crime on Joyce and her loved ones.

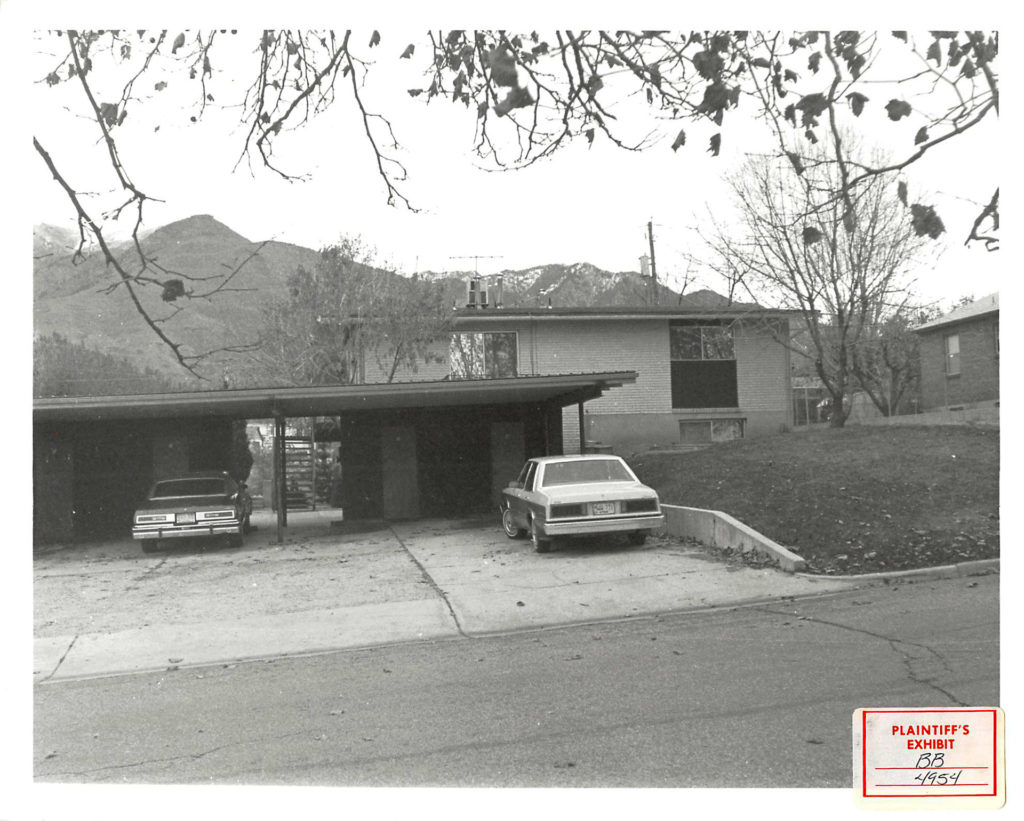

Kim and her husband Randy had sat through Doug’s trial in December of ’85, a trial at which Kim’s own mother — the victim — was absent.

Kim Salazar: They had a woman on the stand and they had a picture of her, of my mom on the stand and they just had that woman read word-for-word what my mom had said during the preliminary hearing.

Dave Cawley: And they’d seen for the first time Doug’s wife, Rhonda.

Kim Salazar: I just remember being disgusted by all of their shenanigans. Y’know, in between. They just came off as this loving couple and it just wasn’t the case.

Dave Cawley: Doug’s convictions were about to put that loving relationship to the test.

This is Cold, season 2, episode 5: Garden Variety. From KSL Podcasts, I’m Dave Cawley.

We’ll be right back.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: Doug Lovell returned to court for sentencing on the afternoon of January 16, 1986. Judge Rodney Page asked defense attorney John Hutchison if there was anything he wanted to say. John said he’d read the pre-sentence report and believed its recommendations were “disproportionately large to the nature of the evidence.”

Judge Page then turned to Doug and asked if he had anything to say.

“Just the fact that I’m innocent,” Doug said.

Judge Page told Doug he believed the case had been proved beyond a reasonable doubt. The jury had got it right. He then handed down the maximum for each of the two counts: no less than 15 years and possibly up to life. The sentences would run concurrently — at the same time — meaning the soonest Doug could hope to be released from prison would be 2001. This was a victory not only for the prosecution, but also personally for detective Bill Holthaus, who told me he remembered John Hutchison’s reaction.

Bill Holthaus: This was not on the record, this was afterwards. He said, ‘My client wants to appeal and I quit.’

Dave Cawley: I asked Bill what he made of that statement.

Bill Holthaus: That he knew he was guilty as sin and did his job and now he was done, is what I made out of it ‘cause I knew, I knew John pretty well. He’d go to bat for his client but he knew he was guilty.

Dave Cawley: But guilty of what? Sexual assault, or something worse? Randy Salazar kept hearing Doug’s words in his head: “she’s gone, buddy.”

Randy Salazar: I mean, that’s pretty much telling you that, y’know what, I had something to do with this.

Dave Cawley: Just days after Doug’s sentencing in the rape case, the city attorney in Washington Terrace dropped all charges stemming from Doug’s June 20, 1985 DUI arrest, the one where he was caught driving drunk toward Joyce’s apartment with a loaded handgun. The prosecutor said abandoning the case would be “in interest of justice” because Doug already faced a long prison sentence. He noted there were other serious charges pending too, presumably a reference to the car theft cases out of Salt Lake City. But Doug resolved those easily. He cut a plea deal and received no additional prison time — no penalty for stealing the car he’d used to kidnap Joyce Yost.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: The Utah State Prison complex occupied a spot at the southern end of the Salt Lake Valley known as “Point of the Mountain.” It comprised several different buildings spread across a square mile of land. The oldest and in many ways most gloomy of them was the Wasatch facility. That’s where Doug began serving his time, on Wasatch’s A-block. Inmates on A-block were housed in cells with Alcatraz-style metal grill doors. This was a big change for Doug who, on his first stint at the prison from ’79 to ’82, had lived in SSD, the Special Services Dormitory.

Doug found himself housed next door to someone he’d met during those earlier years in SSD: a man named Roy “DJ” Droddy.

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): Doug and I lived next door to each other on A Block and we become friends, reacquainted our friendship.

Dave Cawley: I’ll come back to Roy in just a moment. First, I need to acknowledge something significant Joyce’s daughter Kim Salazar had noticed during the rape trial.

Kim Salazar: Rhonda was pregnant with Doug’s baby by then. So she was starting to, y’know, look pregnant.

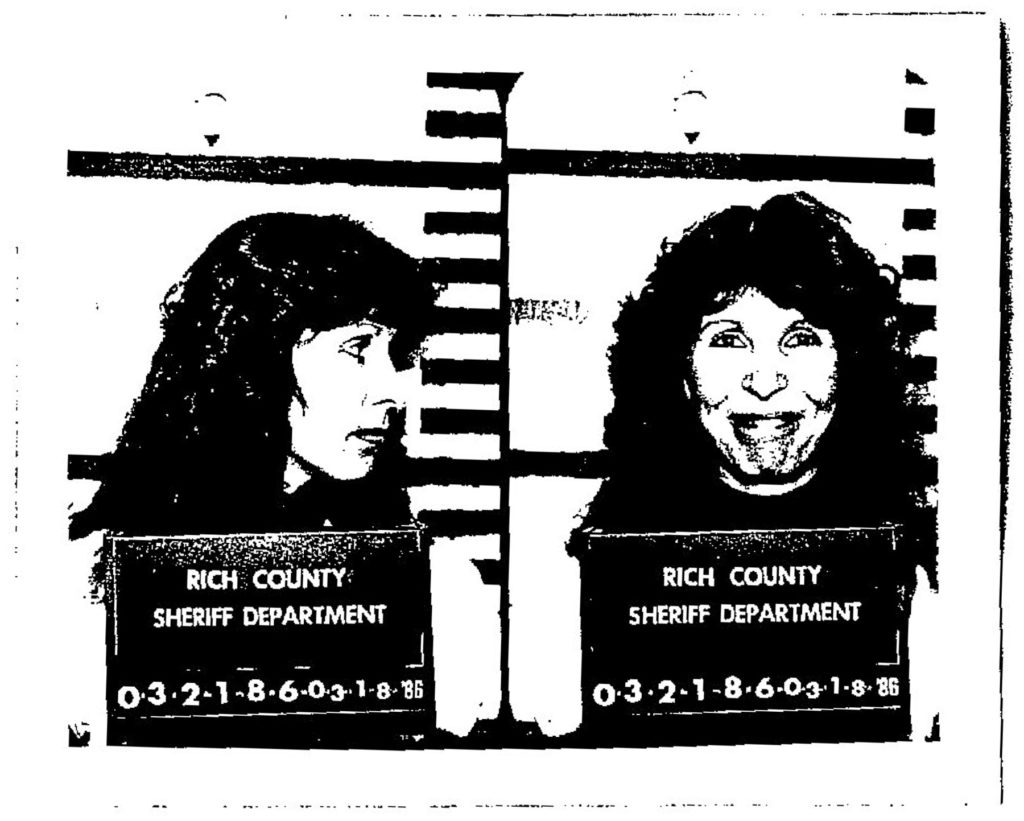

Dave Cawley: Rhonda Lovell worked for the state at an office in the Eccles Building in downtown Ogden. That’s where, on the morning of Wednesday, March 19, 1986, South Ogden police sergeant Brad Birch showed up to serve her with an arrest warrant. Kim had known this was coming.

Kim Salazar: I was in communication with them every day at that point.

Dave Cawley: Brad had learned about Doug and Rhonda having been questioned by a Utah Division of Wildlife Resources officer during a drive through the Monte Cristo mountains. The Rich County prosecutor had decided, on what evidence I can’t tell you, that Rhonda had been involved in poaching.

Kim Salazar: I know that they were trying to get information.

Dave Cawley: Brad told Rhonda they were going over to police headquarters to have a little chat.

Kim Salazar: Y’know, so they used this poaching as a way … to put some pressure.

Dave Cawley: Brad read Rhonda her her Miranda rights. Then, he began to pepper her with questions. This conversation was not recorded. My account of it is based on the written reports of Brad Birch and another detective, Terry Carpenter. Here’s what they said.

Rhonda said she didn’t know anything about any poaching. Doug had not shot any deer on the day of their drive and she hadn’t seen any dead animals. Doug did own a deer hunting rifle, she said — a Weatherby 300 — but she declined to mention the other guns he’d stolen with Billy Jack the prior May.

So, if Doug wasn’t up there to shoot deer, why had they gone to the mountains? Rhonda said they’d tried to go to Doug’s father’s cabin but they weren’t able to make it because they didn’t have a key for the gate. And anyway, the real purpose of their trip was to meet some friends on the far side of the mountain, in a town called Woodruff, to go snowmobiling. Who were these friends, the detectives asked. Rhonda wouldn’t — or couldn’t — provide their names.

Terry Carpenter: Y’know, we wondered about that a lot, how that happened and what went on.

Dave Cawley: Terry Carpenter’s memories of these events were a bit hazy when we spoke…

Terry Carpenter: I don’t remember all the details of that.

Dave Cawley: …which isn’t surprising considering just how long ago this took place. But that’s made it difficult to pinpoint just when the poaching stop occurred. The KSL TV archives show the winter season of ’85 had started strong in Utah.

Reporter (from November 14, 1985 KSL TV archive): It was 24 degrees at Brighton today with a 10-minute line at the Majestic ski lift.

Skier 1 (from November 14, 1985 KSL TV archive): We love it, it’s great.

Skier 2 (from November 14, 1985 KSL TV archive): It is glorious, absolutely glorious.

Reporter (from November 14, 1985 KSL TV archive): Is this the earliest you’ve ever skied?

Skier 1 (from November 14, 1985 KSL TV archive): This is the earliest I’ve ever skied, absolutely.

Dave Cawley: An intense storm had blanketed the high country with snow by mid-November.

Reporter (from November 13, 1985 KSL TV archive): Utah’s winter storm in the last two days left three feet of new snow at the Salt Lake ski resorts. It fell on top of several inches of hardpack snow already in the mountains.

Dave Cawley: So the idea Doug and Rhonda might have had a legitimate snowmobiling rendezvous planned was within the realm of possibility. But…

Reporter (from November 13, 1985 KSL TV archive): Those condition prompted a number of warnings about avalanche danger in the high country.

Unknown (from November 14, 1985 KSL TV archive): We were concerned about conditions and did ask that people stay out of the high country, that we were having problems.

Dave Cawley: …a storm this intense would have forced the Utah Department of Transportation to close the highway that crosses the Monte Cristo mountains.

The available evidence suggests Doug and Rhonda’s Monte Cristo drive happened after Joyce disappeared in mid-August but before the road was blocked with snow in mid-November. That period spanned Utah’s bow and rifle deer hunting seasons, when wildlife officers were on high alert for poachers.

I described Rhonda’s encounter with one such officer in the last episode.

Terry Carpenter: He drove past and noticed that Rhonda was in the car.

Dave Cawley: By herself. A short time later, the same officer had spotted Rhonda in the car again, but accompanied by a man. He’d stopped to talk to her again and Rhonda had claimed Doug was just a hitchhiker. But here, under the scrutiny of the South Ogden detectives, Rhonda had a different explanation for why she’d been alone when the wildlife officer had first approached her.

Terry Carpenter: Doug was out of the car for a minute going to the bathroom.

Dave Cawley: She’d been too embarrassed, she said, to explain this. Terry suspected a different reason for the discrepancy.

Terry Carpenter: It became apparent that she was afraid to say too much around Doug.

Dave Cawley: Brad warned Rhonda if she did not come clean, she was headed to jail. Not the Weber County Jail there in Ogden. They were going to take her way out to Randolph, on the other side of the mountains, an hour and a half drive away.

“Well, let’s go,” Rhonda said.

Terry Carpenter: Rhonda was seven or eight months pregnant. And so we transported her and tried in about every way to help her as much as we could.

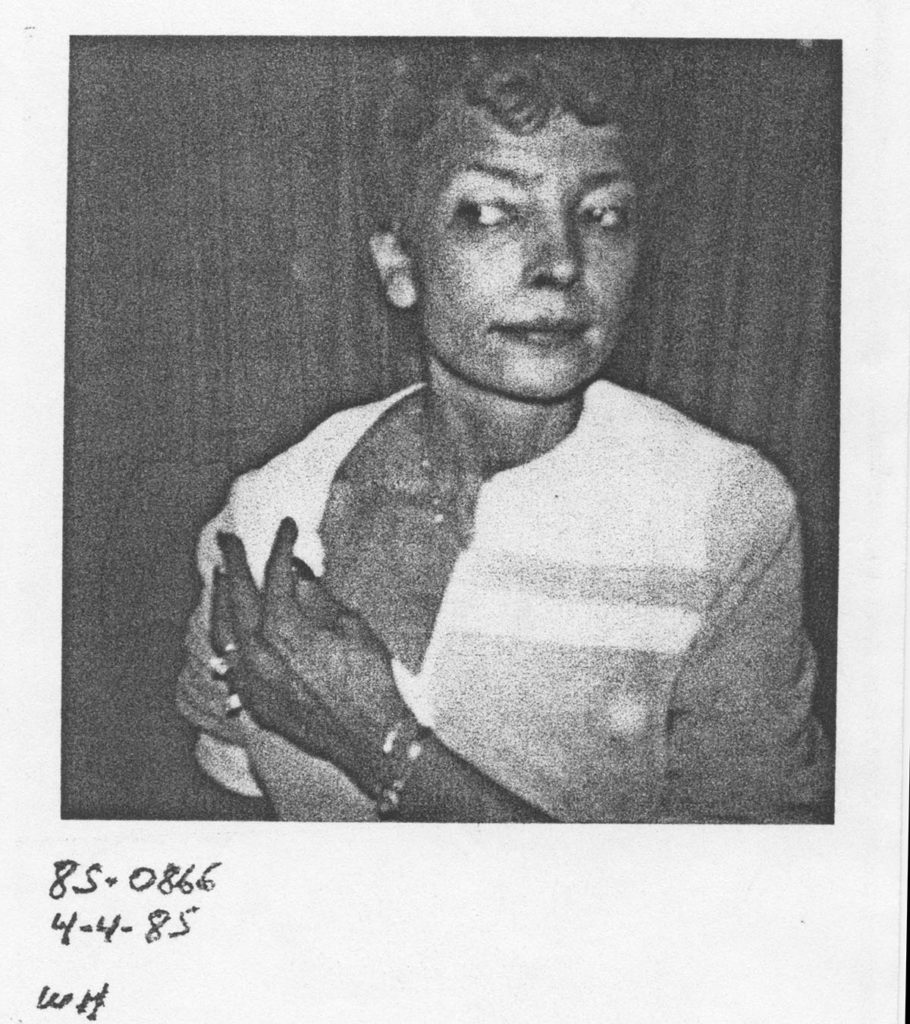

Dave Cawley: I have a copy of the jail booking records. Rhonda is smiling in her mugshot. But she would later describe being miserable that night: 27 years old, husband in prison, several months pregnant, flat on her back on the floor of the jail.

Terry Carpenter: So that was my first contact with Rhonda.

Dave Cawley: The court scheduled a hearing for May 13th on the poaching charge. Rhonda was ordered to appear, along with Brad Birch and Doug, who had to be transported up to Randolph from the state prison. Doug and Rhonda were reunited.

They went before the Rich County Circuit Court judge together. Doug told the judge he intended to act as their lawyer and he wanted to call his wife to testify. This was all a bit much for a minor poaching citation. The judge dismissed the case on the spot.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Utah’s minimum mandatory sentencing law was putting the state’s Department of Corrections in a pinch. The agency had only one prison in ’86 and it was fast running out of space. Planning was underway for a second prison, but as a stopgap the state began shipping some inmates out to county jails.

Roy “DJ” Droddy, who I mentioned a few minutes ago, was among them. He ended up in Duchesne County, home to Utah’s highest mountain peaks, hundreds of natural gas wells and a whole lot of dust and sagebrush. Roy hadn’t been there long before he reached out to South Ogden police. He claimed to have information about the disappearance of Joyce Yost.

Brad Birch drove out to the Duchesne County Jail on June 4, 1986 to talk with Roy.

Brad Birch (from June 1986 police recording): And Roy, what we talked to you about is your involvement with a Mr. Doug Lovell, is that right?

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): Correct.

Dave Cawley: Roy told Brad Doug had enlisted his help drafting legal documents for an appeal. They’d discussed Joyce Yost.

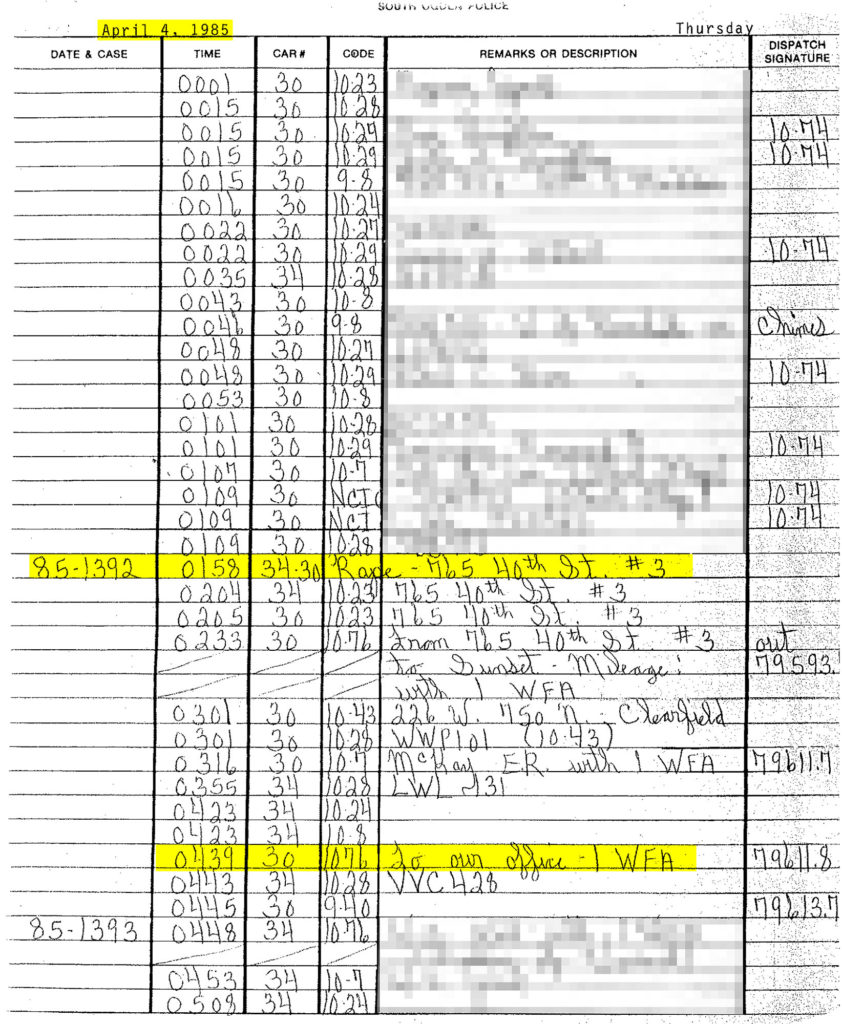

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): He told me that, ah, that that was the young lady he was accused of raping and kidnapping, back in April of ’85 and, ah, in August, ah, he killed her.

Brad Birch (from June 1986 police recording): He made that statement to you?

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): Yes.

Dave Cawley: Roy said Doug had denied raping Joyce, but admitted killing her.

Brad Birch (from June 1986 police recording): Did he say how he killed her?

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): No, he did not.

Brad Birch (from June 1986 police recording): Did he say where?

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): No, he did not.

Brad Birch (from June 1986 police recording): Did he say that anyone was with him at that time?

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): No, he did not.

Dave Cawley: The only real clue Roy was able to provide dealt with what he said were Doug’s efforts to conceal Joyce’s body.

Brad Birch (from June 1986 police recording): In talking about moving the body, when did he say that that happened?

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): Uh, in November, when he was, ah, he was stopped in November for poaching and it was during that time that he moved the body.

Dave Cawley: The poaching stop at Monte Cristo. The details of that were not public knowledge.

Brad Birch (from June 1986 police recording): And he said that he was stopped by fish and game officer?

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): Yes, ah, his wife was stopped and questioned first, and he was not in the vehicle. And the fish and game stopped him a second time, in which he was in the vehicle. He had just come from moving the body.

Dave Cawley: Roy said he hadn’t just learned this from Doug. He’d also heard it from Rhonda herself. They’d talked on the phone about it during the three weeks since the court hearing in the poaching case.

Brad Birch (from June 1986 police recording): Do you think that she knew he was moving the body when they were there originally?

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): In my conversations with her she said no, that she didn’t know, that she thought he was out going to the bathroom or having a bowel movement. She did not know that he was moving the body. I had known because Doug had told me previous to that, but Rhonda did not tell me until, ah, after she had been in jail.

Dave Cawley: Roy’s story, if true, would mean Joyce’s body was in the Monte Cristo Mountains about 30 miles northeast of Ogden. At that very time, in early June, the last bits of winter snow would’ve been melting off those mountain slopes.

I’ve not found any records showing police followed up on this lead. Terry Carpenter told me they tried, but said the information was simply too vague and the Monte Cristo region too vast.

Roy said he’d be willing to testify if the police could ensure his safety. Doug was a dangerous man who’d expressed a desire to have somebody else killed.

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): Right. An officer by the name of John Holtman.

Brad Birch (from June 1986 police recording): Something like that.

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): Right. Right, correct.

Dave Cawley: There’s no person in this story named John Holtman. But to my ear, John Holtman sounds reasonably close to Bill Holthaus, the Clearfield detective who’d arrested Doug the morning after the rape.

Brad Birch (from June 1986 police recording): Do you think he still has the ax to grind against that officer?

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): Yes.

Brad Birch (from June 1986 police recording): Do you think he still would do that if he had the opportunity?

Roy “DJ” Droddy (from June 1986 police recording): Yeah. Because, ah, Doug feels he’s lost a lot and uh, will continue to lose and he feels that the person responsible is this officer Holtman and he’s very bitter towards him.

Dave Cawley: I mentioned this to Bill.

Bill Holthaus: Disappointed he didn’t know my name, but— (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: Grateful, disappointed.

Bill Holthaus: Just maybe a little bit.

Dave Cawley: Bill remembered getting a warning from Brad about a possible threat.

Bill Holthaus: It never came to any fruition. I was apparently, y’know, for sure I was a lot more careful after that for awhile. It went away like everything else. It’s not the first time that a law enforcement officer’s been threatened.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Doug Lovell wanted off A-block. He requested a transfer from the prison’s Wasatch facility to SSD. SSD inmates lived under less restrictive security, qualified for additional recreation time, had a greater array of employment opportunities available and so forth. Space in SSD was limited though and reserved for inmates who were taking part in its programs. Those included sex offender treatment and mental health support for offenders with intellectual disabilities. Doug didn’t have an intellectual disability. He was still publicly denying having raped Joyce, so he couldn’t exactly apply for sex offender treatment. Instead, his stated reason for application to SSD was depression.

Doug Lovell (from recorded phone call): I was uh, I had a very, very low self esteem. I didn’t like myself, I still really don’t. There’s a lot of times I just, for the most part, I just hated me. I hated me and I resented people that, um, that cared a lot about me.

Dave Cawley: That’s Doug’s own voice, captured in a phone call to Rhonda. The prison at the time classified inmates as one of three personality types: Kappa, Sigma or Omega. That correlated to predator, victim or neutral. Doug was a predator-type.

Doug Lovell (from recorded phone call): I’m really a proud person in the sense that I don’t like exposing myself to people and I don’t like letting people, I don’t like telling somebody that I have a problem.

Dave Cawley: Prison staff approved his request and moved him into SSD in the summer of ’87. He began seeing a therapist there, a young woman named Kate Della-Piana.

Doug Lovell (from recorded phone call): When I first started seeing her, y’know, I says ‘y’know, Kate,’ I says, ‘y’know, I feel really bad about, y’know, the first few months that we spent together because I was blowing smoke up your butt.’ She says, ‘I know you were.’ She says ‘it was about to end, too.’

Dave Cawley: Kate did not respond to my interview request for this podcast. Doug also reconnected with an old friend in SSD: Tom Peters. This audio is tough to make out, coming off a very old analog tape, but listen close and you’ll hear Tom say SSD had a good atmosphere and he was able to help inmates with lower ability levels than his own.

Tom Peters (from September 1991 police recording): SSD is a very good atmosphere. It’s mental health. And I’m a psych, I work with the guys who are on the lower ability level than my own, you know? So I work with these guys. It’s very comfortable.

Dave Cawley: Tom had returned to prison in the spring of ’87 on a new set of theft cases. He and Doug often spent their rec time together playing tennis or lifting weights. They didn’t talk about what had happened to Joyce Yost.

Doug kept those kinds of secrets close.

Tom Peters (from September 1991 police recording): God only knows the things he’s done, you know?

Dave Cawley: So it surprised Tom when he started seeing Doug leaving those therapy sessions with Kate Della-Piana.

Tom Peters (from September 1991 police recording): When he goes to therapy with her he’s come out, you know, crying before. He says he’s talking about his brother’s death.

Dave Cawley: Royce’s death was a topic Doug rarely discussed.

Doug Lovell (from recorded phone call): I was caught in between y’know Royce and a lot of situations. Even after he died, I was still, situations that he left me with. Left on my shoulders. And uh, when Royce was around he helped me deal with things, sometimes by not even talking about it. But he was there.

Dave Cawley: Doug had never even been candid about his brother’s death with Rhonda.

Doug Lovell (from recorded phone call): Sometimes when you have secrets, you spend so much time and energy in trying to hide them.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda visited Doug at the prison regularly, bringing the kids Cody and Alisha with her. Only then, in their separation, had Doug started to see Rhonda as his best friend.

Doug Lovell (from recorded phone call): I never thought I’d see that in a woman. And I never realized, y’know, up until now, until lately through my therapy just what the hell, what the hell I had out there.

Dave Cawley: There is another person Doug came to know around this same time, but you couldn’t call him a friend. His name was Carl Jacobson. Carl had taken a job as a corrections officer at the prison in ’83, just as he was turning 22 years old. His first assignment was on A-block, but he transferred to SSD midway through ’86, placing him there shortly before Doug arrived.

Carl’s duties in SSD included sitting in on group therapy sessions for inmates in the Merit Two program, which is what Doug joined when he arrived at SSD in ’87. Carl found Doug easy to manage. He would stop by Doug’s bunk when making his rounds each evening and they’d watch the 6 o’clock news together. Doug, in turn, learned Carl was someone he could safely feed information to when the situation warranted. A symbiotic relationship.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Roy City police dispatcher Betty Nicholas was at work on Friday, April 3, 1987, when, just after noon, she took a phone call. The caller, a man, told Betty he had found a body. He was an avid hiker, he said, and had been back in an area where few people go.

Betty asked the man’s name. He refused to give it, saying he didn’t want to get wrapped up in anything. She reassured him he wasn’t in any trouble, she just needed more information, like an address. All he would say was the body was decayed.

Betty urged the man to call the Weber County Sheriff’s Office, the agency responsible for cases outside of city limits. She told him there were several missing women from the area whom police were eager to find. A little later that same afternoon, Weber County Sheriff’s dispatcher Sheli Tracy received a call from the same man.

Anonymous caller (from April 3, 1987 police recording): I called about Crimestoppers, the number.

Dave Cawley: He wanted information on how to get in touch with Crimestoppers, an organization that allows people to submit anonymous tips.

Anonymous caller (from April 3, 1987 police recording): Well what it, what it, what it was, I’m reporting a body that I found.

Sheli Tracy (from April 3, 1987 police recording): Mmmhmm.

Anonymous caller (from April 3, 1987 police recording): Huh?

Sheli Tracy (from April 3, 1987 police recording): A body?

Anonymous caller (from April 3, 1987 police recording): Yeah, a body that I, that I just just happened across. Way up, you know, it’s way out, y’know it’s not in the communities or anything. It’s way out in the hills.

Dave Cawley: The man said he’d parked his car near Causey Dam, an impoundment on the South Fork of the Ogden River about 20 miles east of Ogden, and hiked two or three miles back into the mountains behind the reservoir. That’s where he’d found the body.

Anonymous caller (from April 3, 1987 police recording): There was a purse there.

Sheli Tracy (from April 3, 1987 police recording): There was, was it a lady?

Anonymous caller (from April 3, 1987 police recording): Well I assume the body was a lady’s but I didn’t open the purse or anything.

Sheli Tracy (from April 3, 1987 police recording): Can I get your name?

Anonymous caller (from April 3, 1987 police recording): No, I’m not interested in leading search parties.

Dave Cawley: Sheli told the man she just needed his name and number so she could have an officer call him, to gather more specific information. He refused.

Sheli Tracy (from April 3, 1987 police recording): Can you explain to me where it’s at?

Anonymous caller (from April 3, 1987 police recording): Well, if you had half an hour.

Dave Cawley: The man said he’d been in the area searching for “sediments” and would have to use a specialized geologic map to pinpoint the spot.

Sheli Tracy (from April 3, 1987 police recording): You won’t give me your name?

Anonymous caller (from April 3, 1987 police recording): I, I, I’m just reporting it. Of, of course not. I didn’t have anything to do with it, you know?

Dave Cawley: Sheli asked if he would wait on hold just long enough for her to grab an investigator. He agreed, but hung up before she returned to the call moments later.

Let tell you a bit about Causey Reservoir. Causey is surrounded by mountain ridges that rise 1,000, 2,000, almost 3,000 feet above the water’s surface. Beyond the reservoir and between the ridges are several canyons, the bottoms of which are thick with vegetation.

These canyons are cut in a 180-degree arc — from 12 to 6 on the face of a clock. Wheatgrass Canyon is at the top and Skull Crack Canyon is at the bottom. Wheatgrass ascends all the way to the base of Monte Cristo — the mountain near where Doug and Rhonda were suspected of poaching.

Skull Crack is home to a private cabin community called Causey Estates. The summer homes there are scattered among stands of quaking aspen and are only accessible through a locked gate. Between Wheatgrass and Skull Crack, to the east, are a series of canyons and ridges rarely visited except by hunters and ranchers. The anonymous caller had not indicated which of these canyons held the remains.

That didn’t stop sheriffs deputies from searching. They went out five days after the anonymous call and combed the area around Causey Dam with no results.

A month later, police in Ogden arrested a man named Cary Hartmann in connection with a series of four rapes committed in 1986 and early ’87.

Larry Lewis (from KSL TV archive): Prosecutors say their key evidence in the case against Hartmann are statements he made to police at the time of his arrest, information from police lab tests and a victim’s testimony.

Dave Cawley: Cary had previously worked as a reserve officer for the Ogden Police Department. Investigators had also discovered he’d been dating Sheree Warren at the time of her disappearance in October of ’85.

Larry Lewis (from KSL TV archive): She was last seen leaving her job at a credit union in Salt Lake to meet her estranged husband at a downtown auto dealership.

Dave Cawley: I mentioned Sheree in the last episode. Police at the time considered both Cary Hartmann and Sheree’s estranged husband, Charles, persons of interest. After Cary’s arrest on the rape charge, Ogden police Captain Marlin Balls phoned Weber County Sheriff’s Lieutenant Archie Smith with a tantalizing lead. A witness claimed to have seen Cary at Causey Estates the weekend after Sheree vanished.

Ball suggested the body the anonymous caller had found could be Sheree. So investigators visited Causey again on June 20, 1987. This time, they focused on the canyon adjacent to Causey Estates but again didn’t find anything. A few months later, a jury convicted Cary Hartmann in the first of the rape cases.

Larry Lewis (from KSL TV archive): The guilty verdict brought tears to family members and even some jurors in the courtroom. The victim agreed to shed her cloak of anonymity and talk with reporters about her feelings, she said as a way to help other rape victims.

Victim (from KSL TV archive): I think if I have the strength to finally be on camera that maybe it will give other people strength through me.

Dave Cawley: Cary Hartmann headed to the Utah State Prison on a sentence of 15-to-life, just like Doug Lovell. And, like Doug, he landed in SSD.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Doug kept his appellate attorney, David Grindstaff, busy during that summer of ’87. Doug still owed on the loan he’d taken out against his stolen Mazda. But responsibility for making those payments had fallen on Rhonda.

Susan Yerage (from 1992 police recording): He was in prison and she couldn’t make, she was gonna have a rough time making payments on it. Especially with the kids.

Dave Cawley: That is Susan, the loan officer who Doug had showered with yellow roses at the beginning of our story. She worked with Rhonda in arranging payments.

Susan Yerage (from 1992 police recording): She got really upset and she said that they were gonna file bankruptcy, which they did.

Dave Cawley: She worked with Rhonda in arranging payments. The appellate attorney, David Grindstaff handled that bankruptcy case. At the same time, David put together a brief for the Utah Supreme Court arguing Doug had been wrongly convicted.

He raised seven points on appeal. First, David said the testimony of Sharon Gess about having been stalked by a red car car with flip-up lights had prejudiced the jury. Second, he said the trial court had given the jury bad instructions regarding venue. Third, he took issue with Judge Rodney Page’s decision to tell the jurors Joyce had been missing for two months. Fourth, he said the prosecution hadn’t established chain-of-custody regarding Joyce’s dress, pantyhose, bra and the blue men’s shirt which were all admitted as evidence. Fifth, he said the sentence was too harsh because the state hadn’t proved Doug’s attack on Joyce rose to the level of “extreme cruelty and depravity” required by the law. Sixth, he said Doug’s trial attorney — John Hutchison — had failed to object to all of the above, meaning Doug was denied effective counsel. And seventh, he said the use of Joyce’s testimony during the trial had deprived Doug of his right to confront the witnesses against him.

The Utah Attorney General’s Office disputed every point. The Utah Supreme Court scheduled oral arguments for December 14, 1987. Rhonda wrote a letter to her husband a couple of weeks before that date. Here’s what it said.

Saige Miller (as Rhonda Lovell): I sure do miss you, honey. I want you home so bad. I can’t stand it. I love you so much. Baby, you are the best. … I hope the appeal will turn out good. I’m excited to go see what it will be like. I hope they hurry with the decision so I can get you home where you belong.

Dave Cawley: On the day of the oral arguments, Brian Namba sat and listened as David Grindstaff made his presentation to the justices.

Brian Namba: He called it a ‘garden variety rape.’

Dave Cawley: A garden variety rape. The comment caught the attention of Justice Christine Durham, the first and at the time only female justice on Utah’s highest court.

Brian Namba: I thought she was going to jump over the bench and strangle him for calling it a garden variety rape.

Dave Cawley: Oh, he said that in oral argument?

Brian Namba: Yeah.

Dave Cawley: Brian told me he’d suspected Doug would try to downplay the callousness of the rape in his inevitable appeal.

Brian Namba: That’s why I filed a written statement, so that it would be in the record and always looking towards appeal and having the Supreme Court be able to have a tangible piece of paper with a list on it of things that are limited to the status of the rape and does not include anything having to do with potential murder.

Dave Cawley: Brian hadn’t wanted the Supreme Court thinking Doug was being punished for killing Joyce, even though he’d only been convicted of kidnapping and sexually assaulting her. On the flip side, the fact Doug had not yet been charged with Joyce’s murder festered like an open wound for her family.

Randy Salazar: Kim is not satisfied with the rape.

Dave Cawley: Joyce’s daughter Kim Salazar and her husband Randy had kept hounding sergeant Brad Birch.

Randy Salazar: Kim is so frustrated ‘cause every time she calls, y’know, there’s nothing they’ve got.

Dave Cawley: They weren’t the only ones in the dark. Detective Bill Holthaus often bumped into Joyce’s sister Dorothy and her kids around town.

Bill Holthaus: Y’know, I was approached a lot, let’s put it that way. ‘What’s going on, what’s going on, what’s going on?’

Dave Cawley: Bill didn’t have anything to tell them. South Ogden police were investigating the disappearance, not Clearfield, and they weren’t sharing information.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: South Ogden police Sergeant Brad Birch promoted to lieutenant at the end of 1987. The move meant he no longer led the investigation into Joyce Yost’s disappearance.

Kim Salazar: My communication with them obviously became less and less over the years.

Dave Cawley: Kim Salazar had kept in touch with Brad and the rest of the detectives, including Terry Carpenter…

Kim Salazar: They were helpful, they were honest I think.

Terry Carpenter: But we were still at a loss as to what’d happened to Joyce.

Randy Salazar: Y’know, Kim’s on this all the time. Kim was constantly calling these guys. Seeing if they found anything out, seeing if they found anything out.

Dave Cawley: Kim and her husband Randy believed they knew right where Joyce’s killer was — the Utah State Prison — even if police couldn’t prove it.

Randy Salazar: But he is cocky down there. He’s very cocky.

Dave Cawley: Terry Carpenter soon moved in to the position Brad Birch had held before him.

Terry Carpenter: I was actually promoted to the detective sergeant and inherited the case.

Dave Cawley: Terry was an Ogden native. He’d attended Weber State College and had been inspired to pursue a career as a police officer by an older brother. He was 15 years into that career by the time he took over the Joyce Yost case.

Kim Salazar: Things had gotten very stagnant until he took over.

Terry Carpenter: Not that anybody had done anything wrong. They’d exhausted about everything that they could.

Dave Cawley: Terry didn’t have much of a direction to follow, at least at first. That changed a few months later, in March of ’88, when Terry received an unexpected phone call from a woman who wanted to remain anonymous.

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): Why don’t you, uh, why don’t you give me the name George.

Terry Carpenter (from March 1988 police recording): George. Ok. I don’t have a problem with that at all.

Dave Cawley: “George” wanted a few details about the Joyce Yost case…

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): She had blonde hair and that she was raped.

Terry Carpenter (from March 1988 police recording): That’s correct.

Dave Cawley: …and asked if it remained an open investigation.

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): Ok, why is the case open?

Terry Carpenter (from March 1988 police recording): Why is it open?

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): Uh huh.

Terry Carpenter (from March 1988 police recording): ‘Cause we’ve never been able to conclude any kind of a location or a whereabouts.

Dave Cawley: “George” said she was speaking with another woman who’d possibly witnessed Joyce’s murder. She wanted an assurance of anonymity.

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): Now I’m getting a little paranoid ok, so—

Terry Carpenter (from March 1988 police recording): I’m under—

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): Why am I paranoid? You won’t put a tracer on this call, will you?

Terry Carpenter (from March 1988 police recording): I understand that completely. That’s—

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): Are you comfortable with that?

Terry Carpenter (from March 1988 police recording): Yes.

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): Ok.

Dave Cawley: Terry told “George” any information she might have could prove valuable.

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): She was murdered by some, a friend of the guy that raped her, who paid someone to kill her. And she was, she was tortured, and umm, killed in a satanic ritual.

Dave Cawley: She said Joyce’s body had then been burned and scattered.

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): Right now I can’t give you any more information. Although, umm, this person said they, they’d be willing to talk to you some time in the future.

Dave Cawley: Terry said he’d do whatever it took to protect this witness, if she would just come forward. George said that couldn’t happen, yet.

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): And I appreciate your kindness.

Terry Carpenter (from March 1988 police recording): Well, thank you. I appreciate your calling.

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): Ok, bye.

Terry Carpenter (from March 1988 police recording): Alright, bye now.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: On July 14, 1988, the Utah Supreme Court issued its decision on Doug’s appeal. The five justices were unanimous. They dismissed every single one of his claims. Chief Justice Gordon Hall authored the opinion, in which he made direct reference to the statement from Doug’s attorney that the rape of Joyce Yost had been of the “garden variety.”

Brian Namba: That was a big mistake on his part. (Laughs). Justice Durham, I thought, boy if looks could kill. I’ve never seen her so mad. (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: That again is Brian Namba, the prosecutor from the rape case. The chief justice wrote there was ample evidence in the record of Doug’s pattern of criminal behavior, as well as his extreme cruelty toward Joyce, to justify the two sentences of 15-to-life. Vindication for Brian, who’d made sure to include those details in his motions. It’d proven tricky, since he’d also had to avoid implying Doug was responsible for Joyce’s disappearance.

Brian Namba: But that’s sort of my strategy is to try to take some of that incendiary stuff out of it, y’know, because you’ve got to keep the record clean. … And so they can look at it and say, ‘Well maybe he did, but here’s all this other stuff that justifies what happened.’

Dave Cawley: The specter of Doug winning release came off the table, much to the relief of Joyce’s family and South Ogden police.

Kim Salazar: We knew he wasn’t going anywhere, so they had time.

Dave Cawley: Did they though? Doug still had two paths to freedom open to him. One went through the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole, where he’d once before won an early release. The other went through the federal courts.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Weber County Sheriff’s Lieutenant Archie Smith had an idea. In September of ’88, he wrote a letter to a man named Murry Miron. Here’s what the letter said.

Ethan Millard (as Lt. Archie Smith): Dear Mr. Miron, I recently attended a psychological profiling course in Salt Lake City, Utah. The instructor … suggested that you are an expert in language analysis and may be able to assist us in a criminal homicide case.

Dave Cawley: Miron held a Ph.D in psycholinguistics, the intersection of how we speak or write and how we think. In the letter, Smith told the story of the caller who’d reported finding human remains near Causey in April of ’87.

Ethan Millard (as Lt. Archie Smith): The caller would not identify himself and we attempted through the news media to try to get the caller to call again with negative results. We searched the area three times with a large force and were still unable to locate a body.

Dave Cawley: Miron is deceased now, but had worked as a professor at Syracuse University and had advised the FBI on several high-profile cases, including the Patty Hearst kidnapping and the Son of Sam serial killings. He claimed an ability to psychoanalyze a person based on little more than their diction and dialect.

Ethan Millard (as Lt. Archie Smith): I am sending to you a copy of the conversation of the caller with our dispatcher, maybe you can tell us a little about the person and how we can go about locating him.

Dave Cawley: Miron’s response came about six weeks later. Here’s what he wrote:

Alex Kirry (as Murray Miron): It is my evaluation that the caller is a high-school educated, white male approximately between the ages of 45 and 60. The dialect markers are consistent with those of a native of the Northwestern United States.

Dave Cawley: Miron said the caller’s claims had the “texture of truthfulness,” with the exception of the statements about his identity.

Alex Kirry (as Murray Miron): In my judgement, the caller did discover a body in an advanced state of decomposition sufficient to have masked the sex of the victim, but is misrepresenting his purposes for being in the area in which he found the body. It is not likely that he was searching for ‘sediments.’

Dave Cawley: Maybe, Miron said, the caller lived nearby or was working on some sort of geological survey. But he said a government employee wouldn’t show so much hesitation in assisting the authorities. It didn’t seem he had any reason for avoiding interaction with the police, beyond the disruption to his daily routine. Miron said appeals to the caller’s conscience would likely fail.

Alex Kirry (as Murray Miron): The caller evidences little moral outrage or indication regarding the fate of the victim or interest in seeing her killer brought to justice. Instead, he appears to be motivated by the pragmatic concern of making the most minimal effort which will discharge what he perceives to be his only nominal civic responsibilities.

Dave Cawley: Miron suggested police play clips of the tape on the news…

Larry Lewis (from KSL TV archive): Investigators believe the body could be that of either Sheree Warren or Joyce Yost, two Weber County women who mysteriously disappeared in 1985 and are presumed murdered.

Dave Cawley: …along with reassurances they did not believe the caller was guilty of any crime.

Lt. Archie Smith (from KSL TV archive): We believe that he did in fact find a body and we desperately need him to lead us to that body.

Larry Lewis (from KSL TV archive): But that may be difficult.

Dave Cawley: Archie Smith enlisted the help of Utah Crime Solvers in putting together this public service announcement which also aired on television that winter.

Terry Pepper (from Crime Solvers segment): The caller stated that he had parked in the Causey Dam area up Ogden Canyon and had hiked two to three miles back into the mountains. While there he discovered the decomposed remains of a body. Because of a purse he found near the body the victim is believed to be a female.

Dave Cawley: The Crime Solvers segment involved a re-enactment of the body’s discovery, along with another plea for help.

Terry Shaw (from Crime Solvers segment): The caller’s description of the area where the body was located was very vague. Several searches of the area have proven unsuccessful. We need to hear from that caller or anyone who can identify the voice of the caller, if only for the sake of the victim’s family.

Dave Cawley: Utah Crime Solvers offered a reward for information about the location of the body or the identity of the anonymous caller. It did not help. The caller never came forward. To this day, he’s not been identified and the remains near Causey have not been located or recovered.

It’s worth noting though the call came in on April 3rd, two years to the day after Doug’s initial attack on Joyce outside her apartment. And more importantly, Doug — who often watched the 6 o’clock news with prison guard Carl Jacobson — saw the Crime Solvers segment.

Terry Pepper (from Crime Solvers segment): Call Crime Solvers about this or any criminal activity. You will remain anonymous.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Rhonda Lovell continued writing her husband letters through the spring of ’89.

Saige Miller (as Rhonda Lovell): It’s just not the same with you not with us. Doug, I love you with all my heart and soul and I never want us to be apart from each other. I would die without you Doug. Us and the kids are one and we can never break that.

Dave Cawley: Doug had a job working in the prison sign shop. He didn’t earn much, but he sent her something every month.

Saige Miller (as Rhonda Lovell): I really appreciate the money you send to us. It helps out so much, honey. I don’t know how I’d survive if you didn’t send money.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda talked about how quickly the kids were growing.

Saige Miller (as Rhonda Lovell): I’ve been thinking about you extra today. We cooked hamburgers and hotdogs outside and it brought back a lot of memories. … It seems like yesterday when you were out on the deck cooking hamburgers for us. What I’d give to have it like that again. We were so happy, so carefree and alive.

Dave Cawley: All of this wistful talk over the idea of Doug winning his freedom. But with every passing month, it became more clear that wasn’t going to happen quickly, if at all. Doug’s therapist, Kate Della-Piana, had reached what seemed a breakthrough during summer of ’89. She’d managed to get Doug talking about the death of his brother, Royce.

Doug Lovell (from recorded phone call): Royce was a very cold person and uh, he was very brutal with certain situations and I never could be like that but yet I tried to be.

Dave Cawley: But Kate was moving on from that position at the prison. Rhonda noticed that with Kate’s departure, her husband’s tone changed.

Saige Miller (as Rhonda Lovell): Why don’t you ever talk about Royce anymore? Just because you don’t see Kate anymore doesn’t mean you don’t talk about it anymore. Please don’t shut me out again, okay? Please talk to me, baby.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda had by then waited four years for Doug to come home. It proved too much. She wrote Doug another letter at the end of that year, telling him she intended to move on with her life. Doug shared Rhonda’s “Dear John” letter with Kate as she was arranging his hand-off to a different therapist.

Doug Lovell (from recorded phone call): She says I, I got a feeling that, y’know, maybe you and Rhonda will get back together. And she looks at me, kinda hoping, y’know that kind of innocent look on her face. And I says, ‘I don’t know.’ I says, ‘Y’know, I kind of think, y’know, that it’s possible that maybe too much has happened between us.’

Dave Cawley: Rhonda had hired an attorney. It turned out to be Steve Kaufman, the man whose band Joyce Yost had gone to see on the last night of her life. Rhonda filed for divorce in late December. In an affidavit, she cited “irreconcilable differences” rising from her husband’s incarceration. She wrote until the divorce was granted, Doug would have “a tendency to feel that he has a strong hold.”

Doug did not contest the divorce. He agreed to pay child support and gave up any claim on their shared property. He only asked that Rhonda hand over his clothing and his bedroom furniture, including his waterbed. By March of 1990, Rhonda Lovell reverted to Rhonda Buttars.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Doug and Rhonda had been divorced for only two months when, in May of ’90, a man named Drew Dunifer dropped by a pawn shop on Ogden’s 25th Street. He brought two guns with him: one rifle and one shotgun. The shop, called 25th Street Pawn, gave Drew $300 for the shotgun.

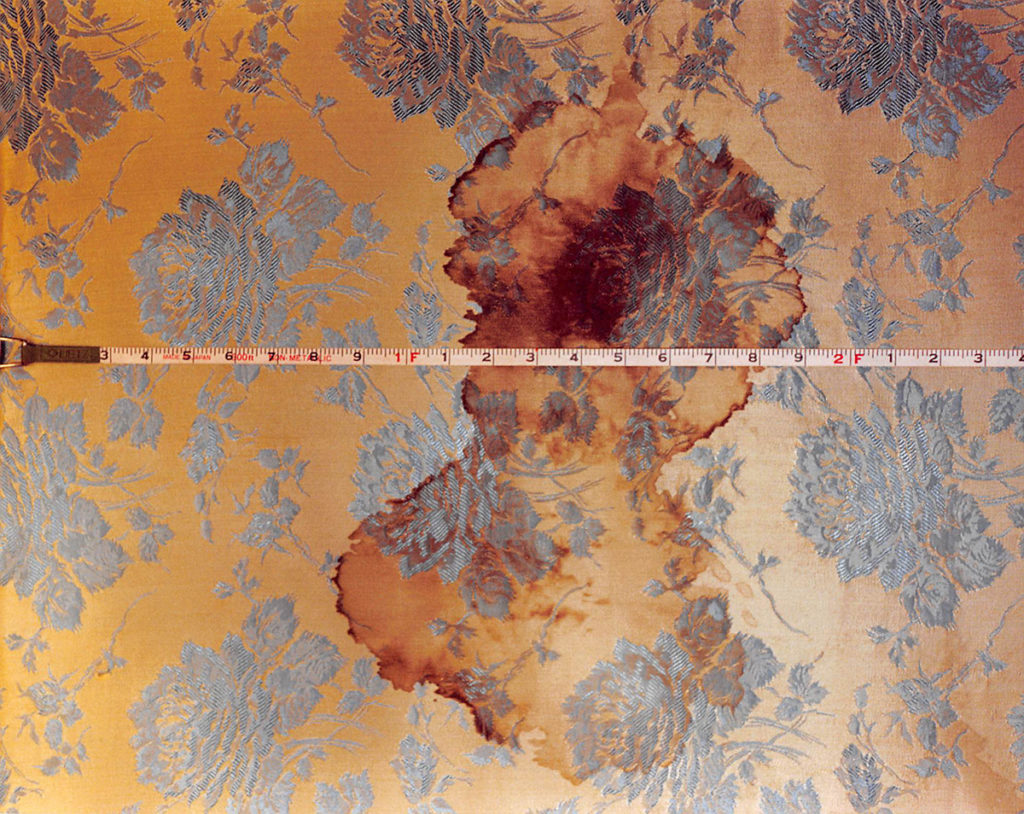

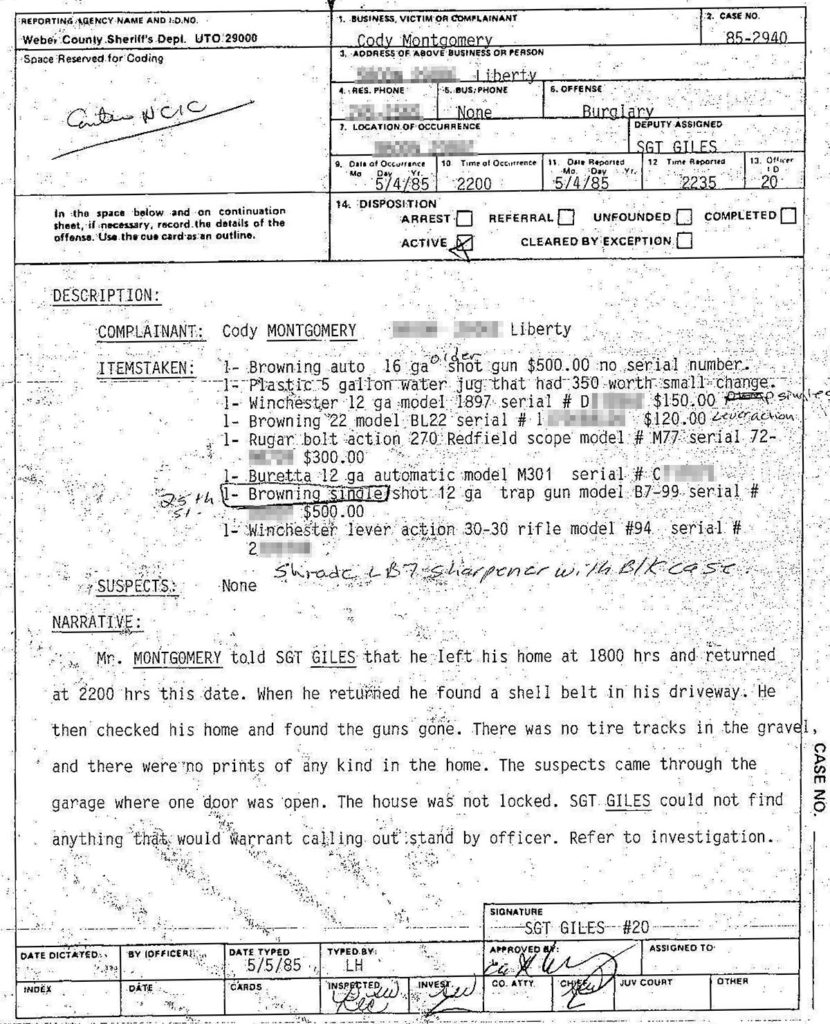

A few weeks later, an Ogden detective stopped by 25th Street Pawn. He checked the shotgun’s serial number. It came back as stolen out of the town of Liberty five years earlier. It was one of the guns taken from the house of Cody Montgomery, Sr. You might remember Cody’s wife, Karen, described that burglary a couple of episodes back.

Weber County Sheriff’s detective Jeff Malan went to 25th Street Pawn several days later and seized the shotgun. The statute of limitations had expired, meaning even if Jeff could figure out who’d stolen the shotgun, he wouldn’t be able to secure criminal charges. Still, he had a duty to return the gun to its rightful owner. And of course, he wanted to figure out how the gun had ended up at the pawn shop.

The shop’s records included Drew Dunifer’s contact information. Jeff worked backward from there. Drew did not respond when I reached out to request an interview, so I can only tell you what the detective’s report and handwritten notes show.

They say Drew told Jeff the gun had belonged to the son of the woman he was then dating. Her ex-husband had bought the shotgun from another pawn shop — The Gift House — in early ’86. When this girlfriend and her ex divorced later that year, the ex had given the shotgun to her son. The woman and her son had subsequently moved in with Drew. That’s how he came to possess the shotgun.

I need to be clear: there’s no suggestion Drew did anything wrong here.

Who had pawned the shotgun the first time, at The Gift House? No one could say.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: The fifth anniversary of Joyce’s disappearance came in August of 1990 with no break in the investigation. But the anniversary brought with it fresh news coverage which breathed new life into an old lead. A bit earlier, I talked about how Sergeant Terry Carpenter had received an anonymous call in March of ’88. The caller had said Joyce’d died in a satanic ritual.

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): And then her body was burned.

Terry Carpenter (from March 1988 police recording): Her body was burned. Hmm. Do you know where this occurred at all?

“George” (from March 1988 police recording): Actually, I don’t.

Dave Cawley: Nothing much had come of that tip, until those news reports around the fifth anniversary. A different woman saw them and reached out to Terry.

Terry Carpenter (from August 1990 police recording): She wishes to explain some of the circumstances that she is aware of involving Joyce Yost. Is that correct?

“Kay” (from August 1990 police recording): Yes.

Terry Carpenter (from August 1990 police recording): Okay.

Dave Cawley: Terry agreed to give this woman anonymity.

Terry Carpenter (from August 1990 police recording): Ah, the other promise that I’ll make you is that when it comes times that we may want your testimony in court, I’ll clarify that with you before we reveal who you are.

Dave Cawley: I’m aware of this woman’s identity but have not had a chance to speak with her myself. As a result, I’m going to honor Terry’s promise of anonymity. I will simply call her “Kay.” Kay told Terry a convoluted story about a friend of hers, a woman named Barbara, who was part of a satanic coven.

“Kay” (from August 1990 police recording): She never went into detail. I know that she still had a goblet and candles and things that they used to use. They used to meet there at this house all the time.

Terry Carpenter (from August 1990 police recording): At the same house?

“Kay” (from August 1990 police recording): Yes.

Dave Cawley: The leader of the coven was supposedly a friend of Doug Lovell’s. Kay said Bee told her this friend had agreed to kill Joyce on Doug’s behalf.

Terry Carpenter (from August 1990 police recording): Did she say how they killed her?

“Kay” (from August 1990 police recording): She said beat, tortured, raped and stabbed.

Dave Cawley: Then, Kay said, the coven had driven Joyce’s body up Weber Canyon and disposed of it along an old dirt road.

“Kay” (from August 1990 police recording): Barbara said that she took her necklace off that she had been wearing and put it on the body. That it was the Italian, you know, the horn style, that style of necklace that was really big in the disco era. That she had put that on the body and that Joyce’s purse had been left with the body.

Dave Cawley: Kay’s account fell right in line with what that caller who’d asked to be identified as “George” had said in ’88, giving the bizarre story an air of credibility. But this claim of a ritualistic killing was also right in line with the popular media of the day.

Jane Clayson (from KSL TV archive): In the last four years, the Utah Attorney General’s Office says it has received dozens of reports of ritualistic abuse. Investigators say it exists, but it’s hard to prove.

Dave Cawley: A full discussion of the so-called “satanic panic” craze of the ‘80s and ‘90s is beyond the scope of this podcast, but prominent figures in media — including Oprah Winfrey and Geraldo Rivera — were around this time broadcasting specials about the perceived dangers posed by satanic cults.

Jane Clayson (from KSL TV archive): But some experts say incidents of ritualistic worship and abuse in Utah are not widespread.

Unknown (from KSL TV archive): It happens, not to the degree people generally claim that it does and I think it often happens in response to publicity.

Dave Cawley: Terry did not dismiss the account, whatever his personal skepticism.

Terry Carpenter (from August 1990 police recording): This, ah, cult or this coven he was involved with, were there other people that participated the night that the killing took place? Except these that you’ve named?

“Kay” (from August 1990 police recording): Only, I don’t know.

Dave Cawley: Kay offered to take Terry out to the house where the coven met. It sat next to a large gravel pit near the mouth of Weber Canyon, about five miles south of Joyce’s apartment. Terry was intrigued. He told news reporters he’d received information from an informant who said Joyce Yost had “met with violence.” The Deseret News published a story with the headline “Clues may aid in Ogden case.”

Terry Carpenter: You want to either prove or disprove every possible lead that you can come on.

Dave Cawley: Terry soon identified and located the woman at the center of the coven claim, Barbara. Terry began meeting with Barbara, attempting to get more information.

Barbara (from April 1990 police recording): I didn’t do anything, I was just there. I didn’t do anything.

Terry Carpenter (from April 1990 police recording): Okay.

Barbara (from April 1990 police recording): And I don’t even know what was done.

Terry Carpenter (from April 1990 police recording): Listen to me. If that’s accurate and that’s the case, then I have no doubt in my mind that the county attorney will grant you immunity.

Dave Cawley: Terry discovered the call from “George” in ’88 had come from Barbara’s psychologist. While in therapy, she’d recovered a memory of a ritualistic murder. She claimed to have once seen a petite blonde-haired woman dismembered by men in black robes.

Terry Carpenter: She believed for all the world that Joyce was one of the sacrifices that her father was involved with and that Joyce was sacrificed and disposed of.

Dave Cawley: But the story seemed to shift with each telling.

Barbara (from April 1990 police recording): How’s it going to look when I’m on the witness stand and say ‘Gee judge, I can’t remember if I was there or not. Gee judge, I have multiple personalities.’

Dave Cawley: You heard that right. Barbara said “I have multiple personalities.”

Terry Carpenter: You could talk to her and you could look to her physically, eye to eye, and she would change mannerisms, she would change voices, she would change from being a total absolute prude to being a sloven, whatever you want to call her.

Dave Cawley: Barbara had been diagnosed with what’s now known as dissociative identity disorder. Which meant Terry needed to speak with whichever personality had witnessed the supposed coven killing. He met with Barbara and her psychologist, intent on drawing out this particular persona.

Barbara (from April 1990 police recording): Got your handcuffs ready? Pull out your gun. And that would hurt me, so don’t.” (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: Barbara bounced between personalities in this audio recording of that meeting.

Terry Carpenter (from April 1990 police recording): Why did they bring her there?

Barbara (from April 1990 police recording): To bring the antichrist.

Dave Cawley: She offered graphic descriptions of a ritual murder.

Barbara (from April 1990 police recording): They buried her in different places.

Dave Cawley: She at times mocked or threatened Terry.

Barbara (from April 1990 police recording): Am I hurting your feelings?

Terry Carpenter (from April 1990 police recording): No, you can’t hurt my feelings. How much hair does this guy have and what does it look like?

Barbara (from April 1990 police recording): Well he certainly has more than you. I have to pick on you. You’re making me hurt.

Terry Carpenter (from April 1990 police recording): You’re right. So that’s fair.

Barbara (from April 1990 police recording): Making me hurt bad.

Dave Cawley: At other times, she pleaded for Terry’s help.

Barbara (from April 1990 police recording): Carpenter, this hurts. Make it stop.

Dave Cawley: I’m being very selective about what I share from this recording, considering the circumstances. But it’s important to know the tape revealed Terry to be a cop who showed compassion. Part of that might be because his relationship to Barbara wasn’t just one of officer and informant.

Terry Carpenter: She was in my ward.

Dave Cawley: A ward is a local congregation of The Latter-day Saint church. Terry was at the time serving as bishop over his ward. That position of leadership in the church’s lay clergy had provided him ample opportunity to get to know Barbara’s various personalities.

Terry Carpenter: She would call as a little boy. She would call as a little girl.

Dave Cawley: But in his role as detective, Terry needed Barbara to give him names of the coven members. And so he had to press her.

Barbara (from April 1990 police recording): Don’t tell. I won’t tell.

Dave Cawley: Terry and a CSI team had already scoured the area around the coven house.

Terry Carpenter: I took canines in, I took cadaver dogs in there.

Dave Cawley: They’d found traces of blood. But forensic testing had revealed that blood didn’t even appear to be human. Near as the crime lab could tell, the blood had come from a chicken.

During a later search of a nearby gravel pit, the crime scene unit located a chip of bone. They likewise sent that off for forensic testing, which proved inconclusive. If the coven existed, and if they’d had something to do with the death of Joyce Yost, they’d covered their tracks.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Four days after Terry Carpenter’s meeting with “Kay,” Clearfield detective Bill Holthaus went into his office and found a slip of paper waiting on his desk. It was a “Phone-O-Gram,” a little form the secretaries used to scribble down messages. This Phone-O-Gram said Sergeant Carpenter from South Ogden had called for Bill regarding a person named “Joey.” Last name: S-C-H-O-S-T. Joey Schost. Bill called Terry back and Terry explained he was making a new push on the Joyce Yost investigation. He had a lot of people he needed to talk to about a new lead saying Joyce had died in a contract killing. Bill had been in the dark about South Ogden’s investigation for five years.

Bill Holthaus: I had no official involvement other than to occasionally ask South Ogden what was going on up until they put the task force together.

Dave Cawley: That was about to change. Bill said he wanted in.

Bill Holthaus: And there were little odds and ends that we did for South Ogden. Interviewing this person, interviewing that kind of person.

Dave Cawley: The biggest interview of the entire investigation was about to come, bringing with it a surprise break.