Dave Cawley: Sean Young, one of the attorneys who’d represented Doug Lovell during his 2015 capital murder trial, met with the attorney handling Doug’s appeal of his death sentence in March, 2019.

That second attorney, Colleen Coeburgh, made an audio recording of their conversation.

Sean Young (from March, 2019 recording): I don’t care what happens to Doug. I used to care. I don’t care anymore.

Colleen Coebergh (from March, 2019 recording): Ok. And I appreciate that.

Sean Young (from March, 2019 recording): He’s a manipulator and a sociopath and I’m done with him. You can tell him I said that. Hi Doug.

Dave Cawley: If you didn’t catch that, Sean called Doug “a manipulator and a sociopath.” But I’m getting ahead of myself here, so let’s a take a moment and review.

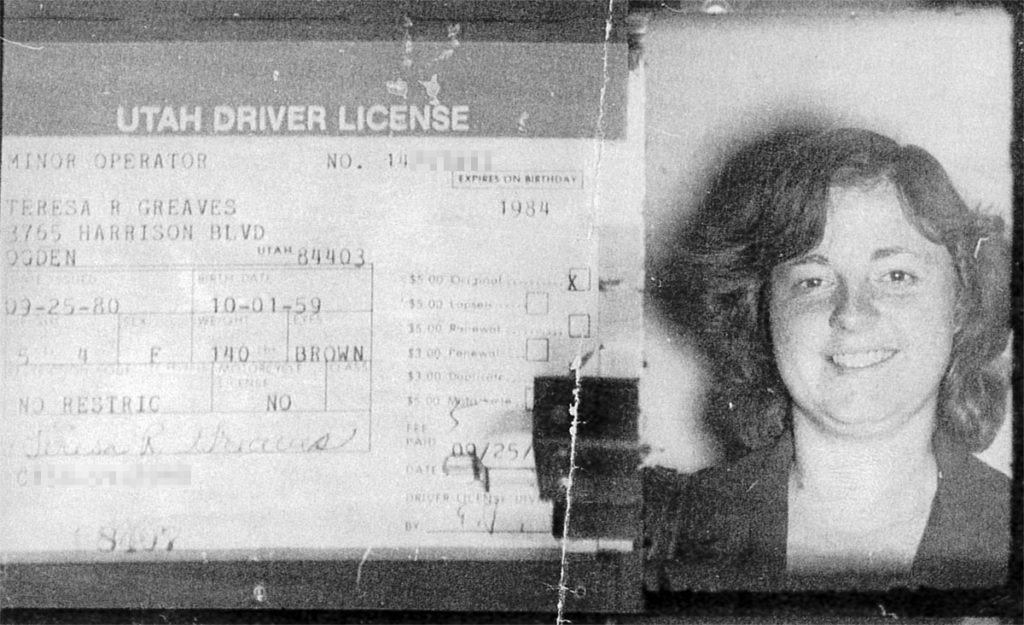

Doug Lovell’s rape and murder of Joyce Yost in 1985 had created a legal mess. His guilty plea to capital murder in ’93 — followed by his conviction for the same crime at trial in 2015 — meant he’d twice received a death sentence. But by 2017, the case had once again become bound up by an appeal. Doug’d had claimed Sean Young had torpedoed the 2015 trial by failing to call many people Doug’d identified as potential character witnesses. He’d also claimed lawyers for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had interfered with the testimonies of several people Sean had called to the witness stand.

Doug also opened a second front on Sean by filing a complaint against him with the Utah State Bar, which he mentioned in this letter to Judge Michael DiReda.

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): The Utah State Bar investigated Mr. Young and on March 2, 2017, voted to direct the Office of Professional Conduct to file a formal complaint against Mr. Young in District Court.

Dave Cawley: Doug’s wasn’t the only bar complaint pending against Sean. There were others rising out of at least 20 different cases. Sean reached an agreement during the summer of 2018 to settle all those complaints. As part of that agreement, he signed a statement admitting fault in Doug’s case.

The statement said Sean had failed to screen all but two of the 18 witnesses assigned to him during Doug’s trial; that he’d failed to question the witnesses who did testify about their beliefs Doug was a remorseful man and that he’d capitulated to the church’s lawyers. A judge suspended Sean’s law license for a period of three years. Sean told the Deseret News at the time he didn’t agree with the claims in the statement, but had signed it simply to put the matter behind him.

Meantime, Doug’s new appellate attorney, Colleen Coebergh, was dogging Sean. She’d learned he possessed hundreds of emails that could be relevant to Doug’s appeal. In a sworn affidavit, Colleen wrote Sean had repeatedly told her he would provide them, then repeatedly failed to do so. She had to ask Judge DiReda to issue a court order demanding Sean surrender his emails, which the judge did. And so that’s why Sean and Colleen met at a courthouse in Salt Lake City, to make that exchange in March of 2019.

Colleen Coebergh (from March, 2019 recording): Ok, you’ve given up every document that you have?

Sean Young (from March, 2019 recording): To Sam, yeah.

Colleen Coebergh (from March, 2019 recording): Ok.

Dave Cawley: Sean told Colleen he disagreed with any suggestion his representation of Doug had been ineffective.

Sean Young (from March, 2019 recording): I did my best to help him. I actually cared about Doug. I did my best I could. I gave him advice. I said, ‘hey, waive your jury, waive the jury and go back to Judge DiReda like you did with judge uh, the original judge on the case.’ I forgot. And he didn’t want to do that—

Colleen Coebergh (from March, 2019 recording): Taylor.

Sean Young (from March, 2019 recording): Judge Taylor. And he said ‘no, Judge Taylor already sentenced me to death one time. I’m not going to waive my jury. I want a jury.’ He said, ‘no jury’s going to convict me.’ And I told him to take the stand. Those were my two pieces of advice that we talked about the whole time. And last thing he backed out. So he, he manipulated me the whole time. And I’m done with him. I’m done.

Dave Cawley: Sean said he refused to spend any more time on Doug.

Colleen Coebergh (from March, 2019 recording): I sit and waste hours and hours on this case. I haven’t been paid a dollar. I’m out $100,000 on this case and I’m kind of done with it. I’m frustrated. You guys get paid, Sam got paid, everyone gets paid except me. I’m kind of sick of it.

Dave Cawley: Sean said he wouldn’t get his law license back, even if the court decided his work for Doug had been up to par.

Sean Young (from March, 2019 recording): You’re not going to help me. You’re not there to help me.

Mitigation expert (from March, 2019 recording): Well we’re, we’re trying to help Doug.

Sean Young (from March, 2019 recording): I don’t care about Doug. He’s a manipulative sociopath. I’m kind of done with him. He manipulated me. He manipulated Sam. He manipulated you. He’s manipulated everybody. It’s what he does. That’s all he does. He’s manipulative.

Dave Cawley: Doug Lovell hadn’t been able to convince a single juror he deserved a chance for parole, but he was about to work his way out of maximum security at the Utah State Prison and one step closer to his ultimate goal: freedom.

This is the finale of Cold, season two, episode 13: Last Chance. From KSL Podcasts, I’m Dave Cawley. Back after this break.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: Doug Lovell happened to be listening to the radio on April 3, 2019 when he heard a woman named Candice Madsen on the airwaves of KSL NewsRadio.

Candice Madsen (from April 3, 2019 KSL NewsRadio archive): With your kids, you want to be the hero, right? You want to be in charge of everything. I think it’s okay for your kids to see you be vulnerable and to let your kids know that you struggle but that you got help.

Dave Cawley: Candice worked as a producer for KSL TV and was promoting a documentary called “Hope in Your Darkest Hour.” The 22-minute program profiled several people affected by suicide, including some who described their first-hand struggles coping with thoughts of self-harm.

Candice Madsen (from April 3, 2019 KSL NewsRadio archive): Life is hard. We can’t do it alone. We just need to reach out and support each other and validate without judgement. I think people are so afraid of being judged.

Dave Cawley: Doug wrote Candice a letter that same day.

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): Dear Ms. Candice Madsen, I just got done listening to you talk about suicide on KSL radio. I thought your comments were spot on.

Dave Cawley: The letter wasn’t the only item Doug put in the envelope.

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): Enclosed is a pamphlet which has a story about a little mouse I crossed paths with here at the prison many, many years ago. I decided last year to write about my experience with the mouse in the hope that it could be used to help prevent suicide here in Utah and elsewhere.

Dave Cawley: The front of the pamphlet included an illustration of a rather plump gray mouse holding a small cube of yellow cheese. Above the mouse were printed the words: Unforeseen Angel. Candice opened the pamphlet and started to read.

Candice Madsen: It was pretty basic. It didn’t give very much information about him other than that he was an inmate.

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): When I was a little boy, our family of five moved out to the country to live on a small farm. I found that I had a love for animals and a special way of connecting with them.

Dave Cawley: Let’s fast-forward through the bits where Doug described his parents’ divorce, his brother’s death and his descent into drug and alcohol abuse.

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): Eventually, I did the unthinkable, for which I was sent to prison — taking the life of an innocent person.

Dave Cawley: He did not bother to say who this person was, or why he’d killed her, but said his arrival at the prison had sent him into a well of depression and “spiritual darkness.”

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): One day, a little, furry-faced mouse came wandering into my cell clearly looking for trouble or an easy snack. This was the happiest moment on A-block. I was happy to give the little guy anything he wanted.

Dave Cawley: Doug spent the next four paragraphs detailing his interactions with this mouse, describing how he’d lured the critter by rubbing peanut oil between his fingertips. He said he’d talked to the mouse, finding it an attentive listener.

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): May sound strange to most people, but that little creature that God put on this earth distracted me just long enough to help get me through the darkest, loneliest, most unstable time in my life.

Dave Cawley: He concluded with a proclamation that all people are children of God with value and purpose. He offered suicide prevention resources.

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): If you find yourself in a very dark place struggling to find hope or purpose in life, please take the first step toward a brighter, happier, more fulfilling life.

Dave Cawley: Doug used the word “I” 30 times in this narrative. The name Joyce Yost did not appear once.

Candice Madsen: This pamphlet was so well produced. Y’know, it was professionally done. So I was kind of, was he able to do that in prison? And so, I just thought that was interesting.

Dave Cawley: Candice turned the pamphlet over and saw a logo on the back. It read “Rising Star Outreach.” Candice showed the pamphlet to a friend, who asked if she knew who Doug was or what he’d done. A quick search through the KSL archives refreshed her memory. She discovered the evidentiary hearing tied to Doug’s appeal had not yet happened, but was just around the corner.

Candice Madsen: And I started thinking, ‘I wonder if he’s just trying to kind of get character witnesses.’”

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Utah 2nd District Court Judge Michael DiReda spent most of the month of August, 2019 on that evidentiary hearing.

Michael DiReda (from August 5, 2019 court recording): Alright, let’s turn to the matter of State of Utah versus Douglas Lovell. This is case 92-1900407. Counsel, will you state your appearances for the record, please?

Dave Cawley: Doug’s appeal of his 2015 death sentence revolved around the idea his defense team hadn’t done a good job. This is a typical step in many death penalty appeals. But the Utah Supreme Court had wanted more information before making a ruling on Doug’s claims of ineffective counsel, so it’d sent the appeal back to Judge DiReda on what’s known as a Rule 23B remand.

Russell DiReda (from August 5, 2019 court recording): This is the time scheduled for evidentiary hearing … On an order from the Supreme Court to this court under Rule 23B.

Dave Cawley: I’ve reviewed hours of this testimony but rather than plow through it all chronologically, I’m going to jump around a bit to better focus on a few particular points. I’ll start with Doug’s mouse. During the hearing, former prison guard Carl Jacobson recalled Doug having once befriended a rodent, but it wasn’t a mouse.

Carl Jacobson (from August 13, 2019 court recording): He had a pet squirrel once — Clusters — trained it and had it in his room for the whole summer. And one day I confronted him and said, ‘y’know Doug, this, this is disgusting. You and your roommate Chewy have done things wrong and you’re in jail for a reason. This squirrel has done nothing. It needs to be out chasing girl squirrels and it needs to be gathering nuts.’ And I says, ‘you keep it in a prison as your little pet. You are disgusting.’ And I left. Next day I come back. Doug Lovell, I go, ‘where’s the squirrel?’ He’d let it go.

Dave Cawley: Kent Tucker, who was married to one of Doug’s cousins, also brought up Doug’s treatment of animals.

Kent Tucker (from August 16, 2019 court recording): So, I’ve always, y’know, you hear about bad, bad guys and usually they don’t want nothing to do with animals. They’ll kill animals and stuff like that. Doug is never, that’s never been his nature. He’s, he just got a kind heart.

Dave Cawley: Kent said he’d seen that kindness all the way back in Doug’s earliest years, when he was just a boy on the farm.

Kent Tucker (from August 16, 2019 court recording): I mean he’s had skunks and squirrels and down at the prison they even had a mink come in that they brought to him and asked Doug if he was interested in this mink which, it was a wild animal, and Doug actually got it to where he could put it in his pocket and he was working at the print shop at the time and he was taking this mink with him to work.

Dave Cawley: So was the mouse mentioned in the pamphlet a real thing? Or was it an amalgam: part squirrel, part mink, part story borrowed from the movie The Green Mile? Doug’s character witnesses painted him not just as a protector of animals, but also as a shepherd of men. Leon Denney, who’d served time in the Utah State Prison in ’88, described how Doug had helped him overcome his anger.

Leon Denney (from August 5, 2019 court recording): I think I stopped hating so much. I was really filled with, with hate. Because … it made me start looking at myself and realizing that, y’know, I had to, I had to step up to the plate.

Dave Cawley: Leon had not testified at the trial, but said he would have gladly done so had Doug’s defense team bothered to ask. Other witnesses told of how Doug had cared for fellow inmates when they were ill or despondent.

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): He encouraged them and he’d say ‘you can still go back to God, you can still get your life right.’ And how do I know that? Because he would say to them ‘if you don’t believe me, write Becky Douglas.’ Well I have had more than 40 prisoners writing to me because Doug Lovell said to them ‘there is a way spiritually for you to come back to the Lord.’ I have been writing to these people.

Dave Cawley: Becky Douglas had discovered in Doug an enthusiastic booster for her non-profit, Rising Star Outreach.

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): The more I got to know Doug, the more I was very impressed with how remorseful he was, how much he wanted to do good, how much he cared about the children at Rising Star.

Dave Cawley: Doug had spent the last decade talking up Rising Star to anyone who would listen. In fact, several of his witnesses — including his bishops — confessed he’d talked them into contributing. Becky said Doug had spent years taking correspondence classes on religion. He’d watched a TV series about the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and another about the New Testament, then sent her letters explaining how each had strengthened his faith.

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): These aren’t the actions of a person who’s pretending to be suddenly come-to-Jesus or religious in order to get a light sentence.

Dave Cawley: And yet, one of the bishops who’d ministered to Doug — a man named Brent Scharman — admitted deep discussion of spiritual matters had been the exception rather than the rule during their Sunday visits…

Brent Scharman (from August 28, 2019 court recording): It was more typically about everyday issues and what was going on in his life and my life and in the world at large.

Dave Cawley: …which led the state’s attorney to ask if Doug’s turn to religion might’ve been an act.

Brent Scharman (from August 28, 2019 court recording): If it’s an act, it’s a very good act.

Dave Cawley: Doug had once told his ex-wife Rhonda you “can’t be in control unless you manipulate. Russell Minas, the attorney who’d helped Doug arrange visitation with his son in the late ‘90s, said he didn’t see their friendship that way.

Mark Field (from August 5, 2019 court recording): You don’t think he’s manipulating you.

Russell Minas (from August 5, 2019 court recording): No.

Mark Field (from August 5, 2019 court recording): And that’s on the basis of telephone calls.

Russell Minas (from August 5, 2019 court recording): Right.

Mark Field (from August 5, 2019 court recording): That he controls.

Dave Cawley: One of those phone calls had come shortly after Doug had received the death verdict in 2015. Doug had called Russell, upset, wanting to know why he’d turned his back on him.

Russell Minas (from August 5, 2019 court recording): He thought that I had changed my mind about appearing to testify. He had no idea why I hadn’t, why I wasn’t there. He felt that I’d betrayed him. I did everything that I could to reassure him that I wasn’t there because nobody ever called me to testify.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: I noticed a pattern as I listened to all this testimony. Day after day, witness after witness, the questioning almost seemed to follow a script. Appellate attorney Colleen Coeburgh would start, eliciting answers that suggested trial defense attorney Sean Young had dropped the ball.

Colleen Coebergh (from August 16, 2019 court recording): Had you had any communications with Mr. Young before he called you to the witness stand such that he would understand and know what you were even going to say when he asked you questions?

John “Jack” Newton (from August 16, 2019 court recording): No.

Dave Cawley: She asked the witnesses who’d dealt with the attorneys for The Church of Jesus Christ to explain what the church’s lawyers had said and done.

Colleen Coebergh (from August 16, 2019 court recording): And what do you think their focus was?

John “Jack” Newton (from August 16, 2019 court recording): Well, I think they were interested in protecting the good name of The Church.

Dave Cawley: Assistant Utah Attorney General Mark Field would then take over. He’d use cross-examination to reveal how little any of these people knew about what Doug had done to end up on death row. That was true even for Leon Denney, who’d met Doug in prison when Doug was still denying having raped Joyce.

Aaron Murphy (from August 5, 2019 court recording): Is it possible that Mr. Lovell really was falsely accused of rape?

Leon Denney (from August 5, 2019 court recording): I, he never told me that. I, I’ve never sat down with him and discussed what he was in for. Ever. … Y’know, it isn’t something you go around asking people what they’re in prison for it can cause just some problems, okay?

Dave Cawley: Mark Field would also point out how none of the witnesses who’d met Doug since he’d received the original death verdict in ’93 had ever interacted with him outside of maximum security.

Mark Field (from August 28, 2019 court recording): Have you ever seen how Doug Lovell reacts when a woman refuses his advances?

Brent Scharman (from August 28, 2019 court recording): No.

Mark Field (from August 28, 2019 court recording): Wouldn’t you think that someone who is capable of murdering another person in order to not go back to prison would be at least as capable of feigning remorse in order to get out of prison?

Brent Scharman (from August 28, 2019 court recording): Sure.

Mark Field (from August 28, 2019 court recording): Ok.

Dave Cawley: The point Mark was making here was that the trial defense team might’ve had good reason not to deeply probe all of Doug’s supporters in front of the jury.

Mark Field (from August 5, 2019 court recording): Because you don’t want to call people who are going to testify that Lovell should have life without parole. Right? You can’t call those people. You can only call people who will say unequivocally ‘Doug Lovell should be out.’ Because if they say anything different, then they’re say— then, the way Doug Lovell’s set it up, it’s got to be death.

Dave Cawley: Remember, Doug had refused to allow the jury the option of life without parole. Mark suggested Doug had for years intentionally kept his supporters in the dark with the singular goal of someday getting out of prison.

Mark Field (from August 16, 2019 court recording): You know, you said that Mr. Lovell is honest. And I want to kind of get to the bottom of that because you’ve also said that you never talked about the crime. Is that right?

Kent Tucker (from August 16, 2019 court recording): That’s right. I think he would have told me if I’d have asked him.

Mark Field (from August 16, 2019 court recording): Well, did he ever volunteer it?

Kent Tucker (from August 16, 2019 court recording): No.

Dave Cawley: This meant each witness was vulnerable to facing those facts for the first time on cross-examination.

Mark Field (from August 5, 2019 court recording): You would let him out of prison because you think—

Russell Minas (from August 5, 2019 court recording): Well, I certainly have heard things here today that I haven’t heard before. So, as you indicated and I acknowledged, it gives me some reason for pause.

Dave Cawley: Mark exposed other vulnerabilities, like how Gary Webster, the former bishop and parole board member, had actually signed the papers that let Doug out of prison early in the armed robbery case.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): That was when you were there at the Board of Pardons and Parole, is that right?

Gary Webster (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Yeah, yes.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): So, I mean, I guess what I’m saying is, how are, how do you know that Doug Lovell won’t do the same thing when he gets out this time?

Gary Webster (from August 12, 2019 court recording): I don’t.

Dave Cawley: What would the jury have made of that statement in 2015, when weighing the choice of giving Doug a chance at parole? I’m going to focus for a moment on the testimony of Becky Douglas, to provide a better sense of how the state’s line of attack worked. Mark asked Becky if she knew about Doug’s conviction for armed robbery in ’78. She said no.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): So, you didn’t know that he’d been released in three years. Right?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Right.

Dave Cawley: This queued up a string of follow-up questions.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Do you know what he did two years later, three years later?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): No, I’m sure you’re going to tell me.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): He raped Joyce Yost.

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): ‘Kay.

Dave Cawley: He drew out each detail of the crime, starting from when Doug had first seen Joyce at the Pier 3.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): He watched her come out of that restaurant. And when he saw her get in her car, he followed her home. Did you know that?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Umm, I knew that. Could I say that what he did was unbelievably heinous and atrocious and horrible. And as a woman, I think as women we all live in fear of this exact kind of thing happening. And I feel for what happened to Joyce Yost. And I feel, and I don’t think I need to know the details of what happened to Joyce Yost. What I need to know is what happened to Doug Lovell after that happened.

Dave Cawley: But Becky was not in control of this narrative. Mark continued, describing what’d happened when Joyce had arrived home.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Did you know that he then looked at her and said ‘you’re attractive, do you want to go have a drink with me?’ Did you know that?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): No. I think I’ve made it very clear that I didn’t know what happened at that time.

Dave Cawley: Mark forced Becky to acknowledge what she knew — or didn’t know — never flinching away from the facts.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Well did you know that after he did that he was aroused enough to then sodomize her? Did you know that?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): No, I didn’t know that.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): He didn’t tell you that, did he?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): I think I’ve been very clear about that.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Is that ‘no, he didn’t tell you’?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Seriously? You don’t think that’s a no? (Laughs) Of course it’s a no. I mean, this is almost, this is almost an insult, right? Can you just simply tell me what you want me to say no to and I’m happy to say no.

Dave Cawley: He asked about Doug’s efforts to hire a hitman who’d then failed to follow through. Becky said that, she knew.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Did you know that he hired a second person?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): I knew that also.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): And do you know that that person said no?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Yes, I read all this on the internet.

Dave Cawley: Mark described the night of Joyce’s murder, how Joyce had begged for her life as Doug force-fed her Valium and drove her into the mountains.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): And he choked her until she was unconscious. Were you aware of that?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): No, but I think if you’ll turn around you’ll see that there is remorse. The man that you’re talking about is crying.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Your honor, your honor, this is not responsive.

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): As you talk about these terrible, horrible things that he did, he’s over there weeping. And you ask me how I know he’s remorseful. I think that answers, that’s one answer to your question.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): So tears to you indicate sincerity?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Well, I think tears show sorrow.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Well, I guess that’s your opinion.

Dave Cawley: Becky came through this gauntlet, only to then face perhaps the most critical question.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Wouldn’t you agree that there’s at least some risk that if Doug Lovell gets out, he may harm another person?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): I think that risk is so low, it’s negligible.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Ok, but it’s not zero.

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): It’s not zero for me either or you either. We all have the possibility of harming another person.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Well, but we know that Doug Lovell raped and murdered another, murdered a woman, don’t we?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Yes we do.

Dave Cawley: Doug’s character witnesses were not unified in their responses to this final question. Some said their newfound knowledge of Doug’s crimes did give them pause in supporting his bid for parole. Others, like former bishop John Newton, equivocated.

Mark Field (from August 16, 2019 court recording): Wouldn’t life without parole just satisfy, be the safest alternative?

John “Jack” Newton (from August 16, 2019 court recording): Well, y’know, you’re saying ‘safest.’ Would it be a safe alternative?

Mark Field (from August 16, 2019 court recording): The safest.

John “Jack” Newton (from August 16, 2019 court recording): Well, that implies that you know how Doug’s going to act in the future. And I don’t and you don’t.

Mark Field (from August 16, 2019 court recording): Yes, but you know Mr. Newton, one of your daughters is now the age that Joyce Yost was when that man raped and took her life. Do you understand that?

John “Jack” Newton (from August 16, 2019 court recording): Y’know, give me the dignity of being a professional. Of course I do.

Dave Cawley: On one point though, the witnesses all seemed to agree: the Doug they knew was not the same man who’d killed Joyce all those many years ago.

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Doug and I have not spoken about this so I think all this is—

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Is what?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Irrelevant. I’ve already testified—

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): I’m sorry, did you just say—

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): —that we haven’t spoken about it.

Mark Field (from August 12, 2019 court recording): —did you just say it’s irrelevant?

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): Yes. Because, because I don’t know that Doug. I only know the Doug that I met in 2007.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: One final point before we move on. During the evidentiary hearing, several of Doug’s witnesses said something like this:

John “Jack” Newton (from August 16, 2019 court recording): And I know on more than one occasion he’s declined an opportunity to be interviewed because he’s concerned that somehow the publicity of this will reach his victim’s family and he feels, in my opinion, a great amount of remorse and is aware of the, at least to some degree, the suffering he’s put them through and doesn’t want to make that worse.

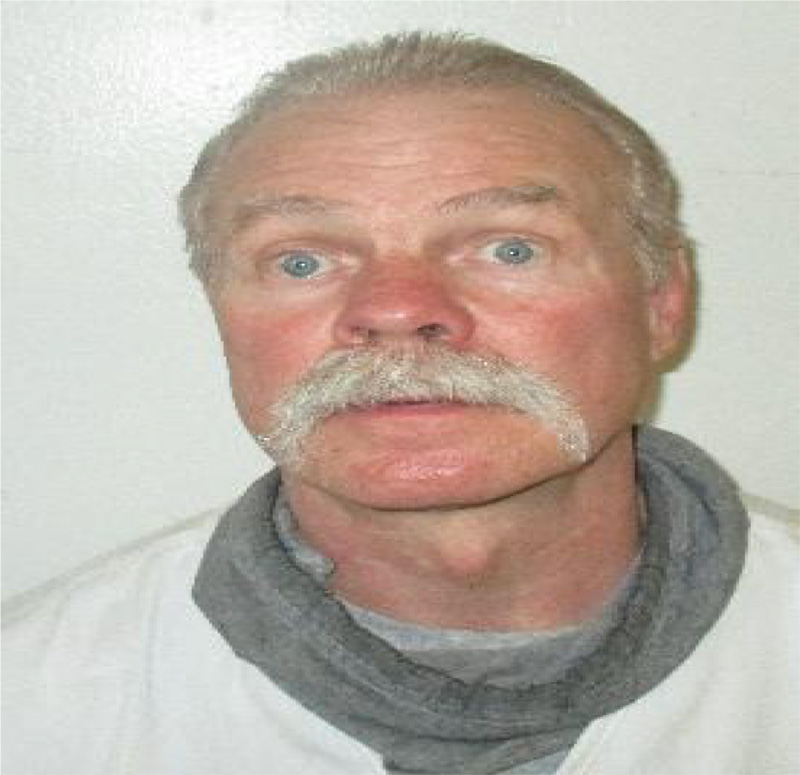

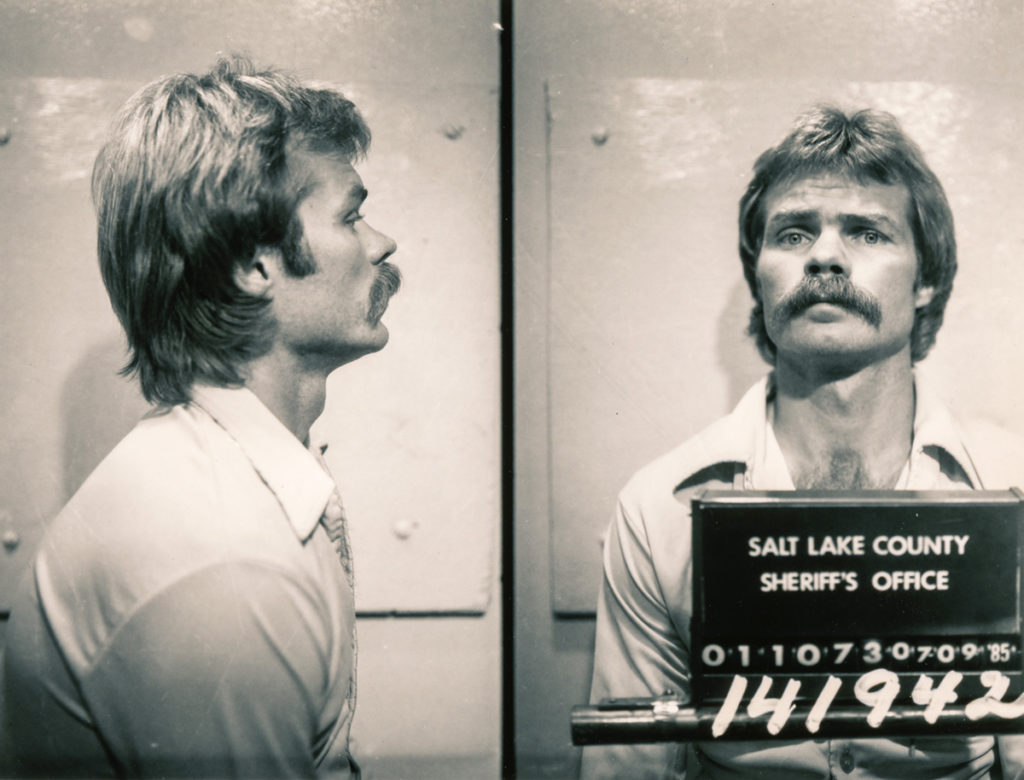

Dave Cawley: Candice Madsen, my colleague at KSL TV who’d received that pamphlet from Doug in the mail, attended parts of the evidentiary hearing. She noted how much older Doug looked compared to his appearance in ’85 or even ’93.

Candice Madsen: And then the other thing that was kind of heartbreaking is, Joyce’s daughter was in that courtroom alone.

Dave Cawley: I asked Kim Salazar about this idea Doug not talking about Joyce was somehow meant to spare her family additional pain.

Kim Salazar: If he were trying to minimize our pain and suffering at this point, we wouldn’t still be on a 23B remand 35 years later. He’d be done. This thing would be done.

Dave Cawley: But it’s far from done.

Kim Salazar: He hasn’t even scratched the surface of the appellate process. We’re still arguing about ineffective assistance of counsel. It’s ridiculous. So he is not trying to spare us anything.

Dave Cawley: Candice wrote a letter of her own to Doug in the fall of 2019.

Candice Madsen: And umm, I just said basically that I was interested in interviewing him. I wanted to bring a producer. … And sent it. I think it was only a paragraph long.

Dave Cawley: Doug’s reply arrived soon after.

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): I appreciate your offer to come to the prison to interview me, but I must decline. When ever I am in the news, I know that it is very upsetting to the family and loved ones of Ms. Yost. Each time I am in court, I believe it is very difficult for them.

Candice Madsen: Well, I wrote back and made it clear that Joyce’s family knew that I had reached out to him and I never heard back.

Dave Cawley: Doug had included another full-color pamphlet containing a different inspirational message about his life in prison published again by Becky Douglas’ charity, Rising Star Outreach.

Candice Madsen: I mean, I believe in redemption and that people in prison should have an opportunity to do good, but I question his motives.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: I’d been working as a radio news producer at the time of Doug’s 2015 trial. I was aware of it then, but only superficially, as the story of a very old murder which had been solved but was back in court on technicality. It wasn’t until Candice came to me and talked about receiving the letter from Doug that my interest was piqued. Like Candice, I dove into the archives. The stories I found all seemed to focus on Doug. It became clear to me that Joyce’s story — like Susan Powell’s — had not been told. I couldn’t shake the feeling Joyce deserved better. So I spent more than a year tracking down sources, digging up old audio, pouring over court transcripts and searching for a secluded mountain gravesite.

Bill Holthaus: Like I say, the only thing I believe is she’s not where he took us.

Dave Cawley: Yeah.

Bill Holthaus: Got to be somewhere else. I can’t believe that he, I refuse to believe that she doesn’t know where she’s at.

Dave Cawley: Bill Holthaus doesn’t believe cougars or coyotes are to blame for Joyce not being on the mountain below Snowbasin. Neither does former South Ogden police sergeant Terry Carpenter, for that matter.

Terry Carpenter: He went back there how long after he killed her and buried her. He knows exactly where she’s at. He knows exactly where she’s at.

Dave Cawley: Joyce’s son Greg Roberts is likewise skeptical.

Greg Roberts: I mean, it’s such an intense situation I know he could take you right to the spot immediately.

Dave Cawley: But where is that “spot?” Police and prosecutors showed with the Joyce Yost case they could prove a murder without a body. But their inability to bring Joyce home has left some deep scars.

Terry Carpenter: My wife and my two little kids went up one time to Snowbasin area to, on a picnic, if you will. And we’re having lunch and I says ‘why don’t we just walk down this area.’ And my wife looked at me and says (pause) ‘you’re still looking, aren’t you?’ I says ‘yeah, I was just walking.’ So we’ve got our little kids and we’re just walking and I’m looking, y’know and all the sudden my wife yells at me and says ‘Terry, what if we find something?’ We tried. She’s not there.

Dave Cawley: Terry is a Christian. He told me he believes in a resurrection. He expects to see Joyce again.

Terry Carpenter: Someday we’ll know. I look forward to that day and wonder if it’s not something that I missed.

Dave Cawley: But the question of where to find Joyce, if not along the Old Snowbasin Road, isn’t the only one still in need of answers. You’ve heard Terry say in this podcast he believes Doug might have killed other people. There are others who call this is far-fetched. And they may be right. I don’t have firm evidence linking Doug Lovell with Sheree Warren, for instance. But Sheree’s case is, like Joyce Yost’s, long overdue for a fresh look. I’ll have more to say about that in the future.

Kim Salazar told me she believes the discovery of her mother’s remains — if it happens — will be a matter of random chance.

Kim Salazar: I don’t believe that even at the 11th hour, if we ever were to reach the 11th hour, that Doug would be the one that would give us that information and I truly in my heart believe that he won’t. So I do think we’re going to have to get there by some other means.

Dave Cawley: Perhaps, as I tend to suspect, Joyce is not far off the side of the highway that crosses the Monte Cristo Mountains, where a wildlife officer observed Doug and Rhonda together in late 1985. That’s a piece of the puzzle that hardly anyone knew about before this podcast.

Bill Holthaus: I did not know about that at all.

Dave Cawley: I’ll show you some documents and—

Bill Holthaus: That’s, that’s, no that’s interesting.

Dave Cawley: I suggested to Bill Holthaus Joyce might be in one of those aspen groves, buried under branches and leaves, out of sight of the hunters who frequent those hills, waiting for someone to step in the just the right spot. Or maybe not. I made a vague reference to this theory in a letter of my own to Doug Lovell. Doug did not respond.

Candice Madsen: And it’s a pattern with him that, y’know, he doesn’t, y’know, wanna disrespect the family or disrespect Joyce’s memory. You’re disrespecting Joyce by not saying her name. By not remembering her. She’s not, I mean we, she is a person. She was a living person. And it’s just, when you read that letter, I don’t think he got it. And I still don’t think he gets it.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: The Utah Supreme Court’s order sending Doug’s appeal back to the trial court for an evidentiary hearing had carried a 90-day deadline. The hearing had not taken place until more than two years later. Judge Michael DiReda had told both sides at the conclusion to submit their proposed findings to him by the end of January, 2020. Doug’s appellate attorney Colleen Coebergh asked for a one-month extension with just days remaining, due to a death in her family. She requested another delay in February, citing “attorney health and workload.” Then, March happened.

Announcer (from March 11, 2020 KSL TV archive): This is breaking news from KSL.

Dave McCann (from March 11, 2020 KSL TV archive): Good evening, we’re following breaking news tonight. Jazz All-Star Rudy Gobert is confirmed to have the Coronavirus, prompting the NBA to suspend the season indefinitely.

Deannie Wimmer (from March 11, 2020 KSL TV archive): This comes as international health officials have declared the coronavirus a pandemic…

Dave Cawley: The Utah Jazz — the state’s premier professional sports team — became a flashpoint in the global spread of Covid-19. Much of American society went into lockdown within hours of that announcement. A magnitude 5.7 earthquake rattled northern Utah a week later. It dealt damage to the building that houses the Utah State Archives.

Garna Mejia (from March 18, 2020 KSL TV archive): Luckily no one was injured. Officials say damages are primarily cosmetic and the building is closed as authorities continue monitoring the aftershocks.

Dave Cawley: Colleen requested another extension, citing these unforeseeable circumstances. Month by month, delay by delay, the goalposts moved farther into the future. Doug lost touch with his lawyer, as he revealed in a letter to the court that July.

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): I have had no contact with my attorney for some time. I have no idea as to what is going on? Please send me a copy of my court docket for the last 90 days.

Dave Cawley: The Utah Attorney General’s Office submitted its proposed findings that fall. Colleen again asked for more time, prompting another letter from Doug in November.

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): I ask this court to not grant Ms. Coebergh any more extensions. Enough is enough. I am very frustrated.

Dave Cawley: Judge DiReda allowed one final delay, but warned if Colleen didn’t submit her proposed findings by the end of January, 2021 — a full year after the original deadline — he would go ahead and issue his ruling without her input. Doug’s attorney did get her proposed findings in, after the deadline. A few weeks later, at the end of February, Judge DiReda released his conclusions.

The nearly 170-page document went against Doug on every point. In short: trial attorney Sean Young had not acted deficiently. A full point-by-point analysis would take more time than I have, so just a few observations.

First, Judge DiReda said he’d found many of Doug’s witnesses lacked credibility and exhibited bias, brought on by their disappointment at the outcome of the 2015 trial. He said many of them had become “hesitant or outright evasive” when confronted with the facts of Doug’s crimes at the evidentiary hearing.

Second, Judge DiReda found no evidence that Church lawyers had threatened any witnesses or interfered with their testimonies.

Third, the judge said the settlement agreement Sean had signed over Doug’s complaint to the state bar after the trial was “unreliable” and contained “numerous factual inaccuracies.” He placed little, if any, weight on what it’d said.

And fourth, Judge DiReda noted it was Doug’s own insistence on refusing to allow the jury the option of life without parole that caused most of his defense team’s problems. Michael Bouwhuis and Sean Young had repeatedly pressed Doug to reconsider. They’d known the best chance of saving his life was to push for life without parole. By denying them that strategy, Doug had effectively limited the value of his own witnesses.

So where does all this leave us now? Doug’s appeal is now back in the hands of the Utah Supreme Court. If the justices allow the latest death verdict to stand, it won’t mean a quick end to the case. Years, if not decades, of additional appeals will likely follow. These could potentially drag the case into the federal courts. And, if Doug loses every step of the way there, he will still have a chance to beg for commutation from the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole. If, on the other hand, the Utah Supreme Court overturns the death verdict, it will pave the way for yet another trial.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: The tragedy is, this all could’ve been prevented right from the start, in the summer of 1985. Doug repeatedly slipped through the fingers of police, the courts and jail staff. But it was Joyce who paid the price for those failures. Utah created a state office for victims of crime two years after Joyce’s rape and murder, in part because it recognized people like her had too often been left to fend for themselves.

Gary Scheller: There would have been much more care and safety wrapped around Ms. Yost to prevent this.

Dave Cawley: That’s Gary Scheller, the head of the Utah Office for Victims of Crime.

Gary Scheller: She didn’t have any knowledge. She didn’t have the opportunity to protect herself.

Dave Cawley: In ’94, the year after Doug’s first death sentence, Utah voters ratified a crime victims bill of rights.

Craig Wall (from October 12, 1994 KSL TV archive): Supporters of proposition number one say it’s an important first step in making the court process more victim friendly.

Paul Cassell (from October 12, 1994 KSL TV archive): What we’ve seen with crime victims in the state of Utah is that they’re treated like pieces of evidence. They’re not really given any dignity at all.

Craig Wall (from October 12, 1994 KSL TV archive): The amendment says victims have the right to be treated with fairness, dignity and respect. They also have the right to be notified of important court hearings. But supporters say most importantly, the amendment says victims don’t have to testify at preliminary hearings. Someone else such as a police officer could do that for them.

Dave Cawley: This point strikes me as significant. It’s a bit of a balancing act, because Bill Holthaus told me the entire rape case might have fallen apart in 1985 had Joyce not testified.

Bill Holthaus: I don’t think if she hadn’t been to the prelim and they hadn’t allowed … the Davis County Attorney secretary to read that, he, he might not have been convicted on the rape.

Craig Wall (from October 12, 1994 KSL TV archive): The argument is, if victims don’t have to take the stand it eases some of the trauma. There is some opposition to the amendment from criminal defense attorneys. But the only aspect they’re really against is the one that would eliminate the need for victims to testify at preliminary hearings.

Richard Mauro (from October 12, 1994 KSL TV archive): A police officer testifying from what a third person told him that’s written in a report doesn’t always accurately tell us what happened in the case. And live witness testimony is the best mechanism available for discovering the truth.

Dave Cawley: The amendment passed in spite of that opposition. But Gary Scheller told me these rights, which are now enshrined in Utah’s Constitution, are largely symbolic.

Gary Scheller: They’re important and they’re critical but at the same time they’re just kind of warm and fuzzy and feel good and have no teeth.

Dave Cawley: What did have teeth was a massive federal crime bill passed into law by the U.S. Congress that same year, spearheaded by a senator who is now serving as President of the United States: Joe Biden. Much can — and has — been written about the more controversial provisions of this crime bill in the years since.

Charles Sherrill (from September 13, 1994 KSL TV archive): The legislation provides $8 billion for new prisons, $7 billion for crime prevention and outlaws 19 types of assault weapons.

Bill Clinton (from September 13, 1994 KSL TV archive): We will finally ban these assault weapons from our street that have no purpose other than to kill.

Dave Cawley: That ban on the possession, manufacture and sale of some semi-automatic firearms has since expired.

Charles Sherrill (from September 13, 1994 KSL TV archive): Lots of new cops can soon be hired with funds from the bill but Salt Lake’s mayor admits it might be hard to meet the payroll when federal funding expires.

Deedee Corradini (from September 13, 1994 KSL TV archive): I’m always concerned about that but I’m willing to take that risk. I think we can do it, I’m quite confident we can do it and we will be applying. We need those officers right now.

Dave Cawley: That bulking up of police ranks has come under increasing scrutiny since the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. The crime bill expanded the death penalty, making many more federal offenses eligible for capital punishment.

Charles Sherrill (from September 13, 1994 KSL TV archive): Fulfilling the President’s promise to get tough on crime will make lots of new work for Utah’s U.S. Attorney.

Scott Matheson (from September 13, 1994 KSL TV archive): We’ve got to get on top of the provisions in this bill very quickly and there are many that could potentially affect our work.

Dave Cawley: But most relevant for the purpose of our story is a portion of that crime bill known as the Violence Against Women Act.

Joe Biden (from August 25, 1994 U.S. Senate recording): We have significant penalties in here to deal with, uh, providing women with some genuine, uh, protection, particularly women who are battered and abused by their spouses, their loved ones quote-unquote, uh, those with whom they’re familiar.

Dave Cawley: Joe Biden, then a Democratic senator from Delaware, had personally authored that part of the package.

Joe Biden (from August 25, 1994 U.S. Senate recording): The only thing in this bill that I wrote from scratch was the Violence Against Women Act. That is a small part of this, maybe that’s why I was so emotionally attached to it.

Dave Cawley: Utah Republican Senator Orrin Hatch had railed against the crime bill, calling it stuffed with pork.

Orrin Hatch (from August 25, 1994 U.S. Senate recording): There are a lot of us who are just plain sick of trying to stop this gravy-sucking hog called the federal government and its liberal friends from eating us alive.

Dave Cawley: But Hatch had supported one small piece — the Violence Against Women Act — even crossing the aisle to co-sponsor that bit with Biden. The Act aimed to close gaps that existed between police, prosecutors, courts and non-profit service providers in their support of victims of domestic abuse, stalking and sexual violence. Its method of doing so came largely in the form of grants: federal money handed off to the states.

Over the past two-and-a-half decades, Violence Against Women Act grants have helped fund domestic violence hotlines and rape crisis centers. They’ve allowed colleges and universities to crack down on stalking and sexual assaults. They’ve provided legal support to survivors. States have come to depend on these funds to provide critical services to women. But those grants are not eternal. They only continue if Congress votes to keep funding them every five years or so. At the time I’m recording this, Violence Against Woman Act funding has lapsed and lawmakers have so far failed to reauthorize it.

Joyce’s experience proves one of the most critical needs for any survivor is information. Think back to that question she asked only hours after her rape: how safe am I?

Joyce Yost (from April 4, 1985 police recording): He, he kept threatening me that if I didn’t cooperate and if I didn’t go with him, it was going to be the end of it for me.

Rob Carpenter (from April 4, 1985 police recording): That’s exactly how he put it, it was just going to be the end of it for you?

Joyce Yost (from April 4, 1985 police recording): Yeah, he was going to rip my vocal cords out here.

Dave Cawley: Joyce’d had no way of tracking Doug Lovell in the weeks and months after his arrest. Was he in jail, out of jail? She didn’t know.

Gary Scheller: For a long time, that was really kind of treated as none of the victim’s business, what we’re doing with this person.

Dave Cawley: Again, that’s Gary Scheller from the Utah Office for Victims of Crime. He told me most states now use a system called VINE to keep people like Joyce informed about their attacker’s status.

Gary Scheller: They can receive a notification if they’re going to be released, if they have a hearing coming up with the Board of Probation and Parole, if they’re moved from one facility, correctional facility to another they get a notification. So they can have some, some piece of mind knowing that they’re at the moment safe.

Dave Cawley: Technology also now allows cops, courts, probation officers and the like to more easily share information across jurisdictional lines. But lapses can and do still happen because people make mistakes, exhibit bias, are overworked or undertrained or just burn out and stop caring.

Joyce had trusted that the system would protect her. But her son Greg Roberts told me she’d also just wanted to move on with her life.

Greg Roberts: She didn’t tell me that she had been raped until a couple months after it happened. And then she really played it down.

Dave Cawley: Joyce’d feared the humiliation of being labeled a victim and having her private life dissected in court, as she’d seen happen on TV. That’s less likely to happen now than it was in ’85, because of state and federal rape shield laws. These laws say defendants cannot use information about an accuser’s past sexual behavior or sexual predisposition as evidence, with only a few narrow exceptions. But while shield laws have strengthened protections in the court of law, one look at social media will show they hold no sway in the court of public opinion.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Retired Clearfield police detective Bill Holthaus told me he thinks the chances of Doug ever getting out of prison are low. But maybe that’s not the point.

Bill Holthaus: I think that is the glimmer that he’ll someday get out. I personally believe that he could con people then and he can con people now.

Dave Cawley: Back in episode 8, I described how prison staff moved Doug into maximum security in ’92, after Terry Carpenter served him with the murder charge. Doug had gone from living in a dormitory setting, where he was free to work and interact with others, to spending all but three hours each day locked alone in his cell.

Doug Lovell (from May, 1992 prison phone recording): I’m hoping we can get this straightened out, y’know, pretty quick with the attorney and whatnot. ‘Cause I’d like to go back to work at the sign shop. I hear they’re keeping my job for me, but, y’know, they can’t keep it forever.

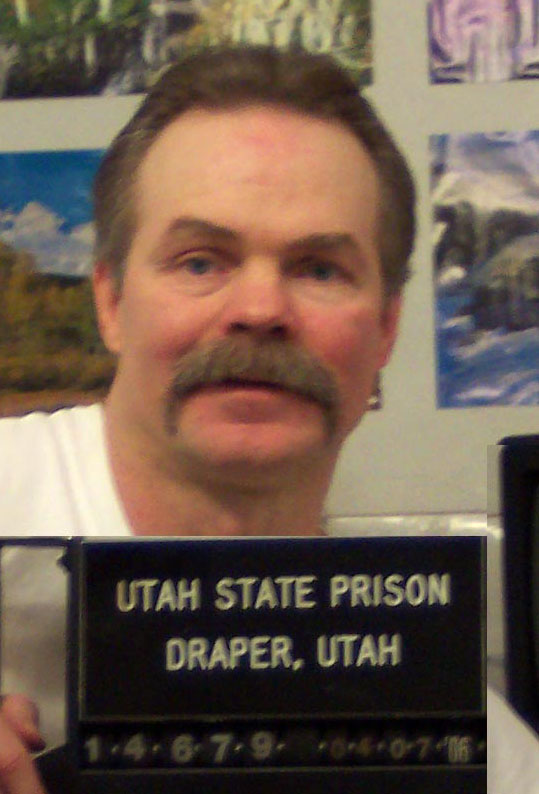

Dave Cawley: When Doug wrote to my colleague Candice Madsen in 2019, the envelope showed he’d sent the letter from Uinta 1: the maximum-security cell block at the Utah State Prison that for decades has housed the state’s death row inmates. But something interesting has happened in the time since. The Utah Department of Corrections moved Doug out of max. He’s now living in medium security. I’ve been told he has a job again, working in the prison’s welding shop. Fewer fences now separate him from the outside world.

I was curious why this change, so I asked Corrections Director Brian Nielson to explain it.

Brian Nielson: Those that have a death sentence, they’ve been in very restrictive housing traditionally for a very long time, without the option to do anything else.

Dave Cawley: Brian wouldn’t talk specifically about Doug’s case, but said the department implemented a policy in 2005 called “Last Chance.” He says it allows inmates to earn their way out of max.

Brian Nielson: So they’ve really had to demonstrate that they can function in that setting ahead of time and then we test the waters in small incremental ways to help them get there.

Dave Cawley: But something doesn’t add up, because at the time I’m recording this, the department’s own website says the policy doesn’t apply to death row inmates. The website says the only way off of max for them is to have their convictions overturned or sentences commuted. Which contradicts what Brian told me.

Brian Nielson: We’ve had a couple make it that far but it’s taken, y’know, 13, 14 years to get there.

Dave Cawley: More than a couple. Prison records show of the seven inmates under sentence of death in Utah in June of 2021, only two of them are still in maximum security at the Uinta facility.

Brian Nielson: That risk is going to be inherent in that process and we keep our guard up all the time while looking for opportunities to help people advance.

Dave Cawley: There is logic in allowing inmates a path forward. The vast majority are only in prison temporarily. It’s the goal of the department to help offenders change their ways and avoid coming back once released. Even people serving life without parole sentences might be easier to manage if given an opportunity to better their own situations in some small way. But Utah’s courts have twice said Doug should die for what he did. Which means the state now finds itself in the awkward position of simultaneously arguing in court Doug is a manipulator who’s conned people into supporting his bid for parole, while at the same time granting him additional freedoms based on his ability to convince prison staff and social workers he’s not a threat.

Bill Holthaus: And I know these are professional counselors that he’s with. Y’know, I understand that and they got a lot of training and so do I, but he’s a con artist.

Dave Cawley: I requested a copy of the Last Chance policy under Utah’s public records law. The department refused to provide it, claiming it was “protected” because release could interfere with investigations or audits. Doug Lovell murdered Joyce Yost to keep her from testifying. He tampered with Tom Peters to try and intimidate him into not testifying. He used his last stint on the outside, after convincing the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole he’d changed, to rape and to kill. How does all that balance now against Doug’s good behavior while in prison?

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Two part question. One: does he have a realistic chance of ever getting out of prison? Two: does he have a realistic chance of ever being put to death?

Bill Holthaus: One: no. Two: also no.

Dave Cawley: Bill Holthaus told me he believes it’s unlikely prosecutors will win a death verdict a third time, if Doug gets yet another trial.

Bill Holthaus: If there’s another jury here, it’s going to be a jury of people who weren’t even born when this happened and they’re not going to be able to relate. … But I think he’ll be convicted again, if we go back to trial. The evidence was good, it’s still good and I have no doubt. But I would be surprised if they once again pursued the death penalty.

Dave Cawley: Utah has not executed a death row inmate since 2010. It hasn’t added someone to death row — excepting Doug’s 2015 return — since 2008. Utah’s Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice released a report a few years back that noted public support for the death penalty in the U.S. has waned to its lowest point since 1972. The report cited a Gallup poll which showed death penalty support in the 1990s — when Doug was first sentenced to death — was near 80-percent. As of a few years ago, that had fallen to about 55-percent.

As of 2020, half of the states in the U.S. had abolished the death penalty or placed capital punishment on indefinite hold. Joyce’s family, meantime, remains steadfast in their push to see Doug Lovell die…

Greg Roberts: I don’t see it ever happening.

Dave Cawley: …even though Greg Roberts acknowledges they are swimming against the currents of culture and criminal process.

Greg Roberts: That’s why I just don’t know if they’ll ever carry it out in this case because it’s still got so many years to go.

Randy Salazar: Do I think in my lifetime that I’ll ever see Doug get the, the death penalty. Will it, will it ever go through? No.

Dave Cawley: Kim and Randy Salazar have each been ground down by the decades of never-ending court hearings.

Randy Salazar: And Doug, if you were any kind of man, you’d be dead right now because you’d ask for the death penalty just to be over with.

Dave Cawley: Neither believes Joyce’s killer will ever win parole.

Kim Salazar: Somewhere in his mind he believes he’s going to. I mean, I think he really believes that some day he could walk out of there.

Randy Salazar: The taxpayers have paid so much money for him to be down there and to get lawyers and tell his side of the story … Well, the son of a bitch is guilty. And you sentenced him to death. Get it over with.

Dave Cawley: Meaning Doug Lovell might just remain in limbo until the day he dies of natural causes, as has happened to two other Utah death row inmates in recent years.

Kim Salazar: I think that we have a better chance of him dying of old age in there than we do of him dying by the hand of the state.

Randy Salazar: Do I think that’s fair? Absolutely not. Absolutely not. But do I hope one day that he has to see Joyce again? Hell yeah. And do I hope that Rhonda has to see Joyce again? Hell yeah.

Dave Cawley: I’m not here to advocate for Doug’s life or death. It’s not my intent to take a position on capital punishment. But it’s worth considering the collateral damage of a case like Doug’s. The justice system finds itself struggling to balance the cries for vengeance from people like Joyce’s ex-husband Mel Roberts…

Mel Roberts: I’m probably the one person that could’ve got on an airplane, went up there and shot that son of a bitch, got up and left and got away with it and nobody’d have known the difference. And trust me, I thought of it. I swear to God I thought of it.

Dave Cawley: …against Doug’s civil rights and the pleas for mercy from people like Becky Douglas.

Becky Douglas (from August 12, 2019 court recording): When you talk to someone and they’re crying so hard they can’t talk to you because they feel so bad about what they’ve done, that’s, you say angry, angry with himself. Yes. He was furious with himself over what he had done.

Dave Cawley: It is, perhaps, an impossible balance to strike.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: A bit earlier I talked about how I first came to know Joyce’s story. What I didn’t tell you was the sense of dread I felt at taking on the assignment of telling it. I knew from the outset I would have to contend with a very sensitive topic. I worried about all the mistakes and missteps I might make as a man in this space, trying to share Joyce’s perspective.

It was, in some ways, similar to how I felt in season one, telling the story of Susan Powell’s abusive marriage. The difference is Susan left us a better record of her thoughts, actions and feelings. Much of what I know about Joyce’s life comes only secondhand. Yet the more I’ve learned about Joyce as a person, not just as a name in a news story, the more empathy I’ve gained for what she went through.

Look, I enjoy a place of privilege in society as a white heterosexual man. Strange guys don’t follow me home when I go out to dinner with a friend. I’ve never worried that a woman might grab me by the throat and tear my clothes off outside my own house. This privilege can breed complacency. It can make me blind to what Joyce and so many other women experience every day. And that is injustice.

This season bears a subtitle — Justice for Joyce — and I have to be honest: I don’t love it. It seems trite to me. It doesn’t capture the way I felt the first time I heard Joyce’s voice in that tape recording with Bill Holthaus just hours after her rape. It can’t convey how I hurt for her when I listen to her voice cracking saying the words “I have been raped.” How I still break down and cry when she asks a police officer “how safe am I?”

“Justice for Joyce” reduces what she went through to a tagline. And I hate that. I voiced this complaint and was challenged to come up with something better. And I couldn’t do it.

Bill Holthaus: There is no justice for Joyce. Let’s preface it by saying that. When you kill somebody, you kill somebody. There’s no such thing. It’s justice for what he did to Joyce.

Dave Cawley: Joyce hadn’t wanted to go to detective Bill Holthaus after Doug Lovell followed her home, raped her, kidnapped her and raped her again. She’d simply wanted what so many other people who experience unexpected trauma want: a return to normalcy and a restoration of safety. Joyce would have been justified if she’d chosen to stay silent. But she spoke up because she felt a responsibility to help protect whomever Doug might’ve targeted next. And for a brief moment it seemed the system might work. Bill believed Joyce. Doug landed in jail. She spoke her truth in court.

Then, all the mechanisms of law and civil society that were meant to protect her failed. The people who were closest to Doug repeatedly rewarded him — the handsome white guy from a good Christian family — with the benefit of the doubt, even after he’d proved he didn’t deserve it. They chose to believe him when he said he’d been falsely accused, or at least decided to look the other way.

Some are still doing so even today, dissociating the Doug they know from the one who chose to kill Joyce Yost.

Joyce paid for her courage with her life. So what message does that send to every other woman who’s ever been groped, catcalled, stalked, assaulted or raped and feared coming forward? Imagine the tragedy of a Joyce who’d lived by keeping the rape a secret, spending her entire life plagued by undeserved guilt and self-doubt, wondering how many others that man had gone on to terrorize.

How many men have allowed — still allow — their privilege to blind them to what so many women endure in silence? I don’t want to be one of them.