Dave Cawley: Doug Lovell’s relationship with his ex-wife Rhonda Buttars had soured, so much so that on Sunday, May 10, 1992 he’d told her off in an angry letter.

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): I have done everything I can to be a friend to you Rhonda. I have never bad-mouthed you behind your back & I have treated you as kind as possible on the phone.

Dave Cawley: You’ve heard most of his this already, at the end of the last episode.

Richie Steadman (as Doug Lovell): As I said earlier Rhonda, you win! You don’t need to hide behind the answering machine, or ask the kids to lie, or even make up lies yourself, I won’t call, write or send anything anymore.

Dave Cawley: What you didn’t hear was the aftermath. Days later, on Wednesday of that same week, Weber County Attorney Reed Richards signed a formal immunity agreement for Rhonda. This was something South Ogden police sergeant Terry Carpenter had promised Rhonda more than a year earlier.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): There was an agreement made between you and I that immunity would be sought for you, and that there would be no charges filed against your, per se your involvement with Joyce Yost. Is that correct?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Yes.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Okay. And there was a condition I put on that. Do you remember what it was? That provided you didn’t pull the trigger, we wouldn’t have any problem with that.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Right.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): And the reaction was, to that, was that she hadn’t been shot. Is that right?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Right.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Ok.

Dave Cawley: But that original verbal agreement had not carried the force of law. Rhonda had incriminated herself without a signed and sealed immunity agreement.

Terry Carpenter: That’s really the first solid lead that we had, that she knew and that Doug had done it. We knew he’d done it, but we could never prove it.

Dave Cawley: Terry’s entire case depended on Rhonda. She’d spent months assisting his investigation with no lawyer, no safety net.

Terry Carpenter: We got so much information from her that we would never have gotten without her.

Dave Cawley: She had twice worn a wire into the Utah State Prison, placing immense trust in Terry.

Rhonda Buttars (from January 18, 1992 wire recording): I don’t do court. You’re not listening.

Doug Lovell (from January 18, 1992 wire recording): You do well in court.

Rhonda Buttars (from January 18, 1992 wire recording): No I don’t.

Doug Lovell (from January 18, 1992 wire recording): Yes you do. If you look at your track record, they’ve never been able to keep you.

Dave Cawley: The time had come for Terry to reward that trust. The formal agreement signed on that day in May of ’92 promised Rhonda would receive “transactional immunity” from charges, like the capital murder case prosecutors were about to at long last file against her ex-husband.

This is Cold. Season 2, episode 8: Help Me, Rhonda. From KSL Podcasts, I’m Dave Cawley. We’ll be right back.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: The ink had barely dried on Rhonda Buttars’ formal immunity agreement when, on Thursday…

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): The date today is the 14th of May, 1992. It’s approximately 1602 hours.

Dave Cawley: …Doug Lovell received word he had a visitor.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): This is Terry Carpenter. I’m currently at the Utah State Prison awaiting Doug Lovell to come and talk with me.

Dave Cawley: Terry had brought a summons, ordering Doug to appear in court to answer for charges related to the disappearance of Joyce Yost. The counts included capital murder, aggravated kidnapping and aggravated burglary.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I want to give him a chance to talk to me. I hope he will talk to me.

Corrections officer (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I hope so, too.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I’ll be surprised, but I, I want to at least give him the opportunity to.

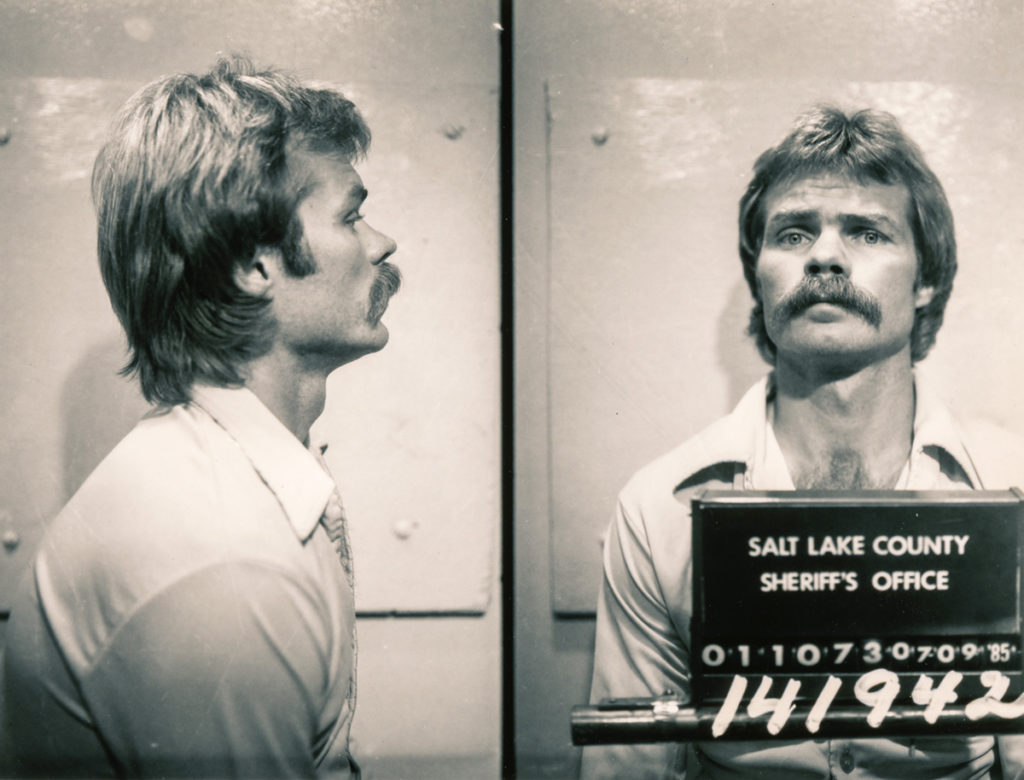

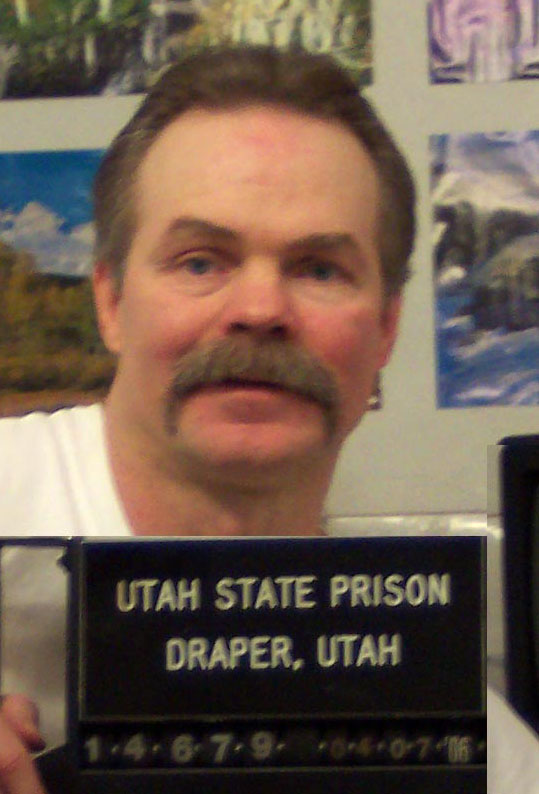

Dave Cawley: It’d been more than seven years since Doug had first followed Joyce home and raped her, a crime that had landed him in prison. Doug was living in SSD, the prison’s special services dormitory. Colleen Bartell, a social worker at the prison, had made space for him in a group substance abuse therapy program there earlier that year. Doug was in the middle of one of those group sessions when a corrections officer came to get him. Doug headed over to the prison offices where Terry was waiting.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): How you doing?

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): How you doing?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I’m doing good. Good to see you.

Dave Cawley: It was almost a year to the day since Terry had last visited Doug at the prison and told him he intended to charge him for Joyce’s murder.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Doug, I’m keeping promises today.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Alright.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): ‘Kay. Uh, come down to talk to you. If you want to talk about it. I’m here to serve you with a summons on a capital murder.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I don’t know what to say.

Dave Cawley: Doug eyed Terry’s micro cassette recorder. Terry reassured Doug he could speak freely.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): It’s not on. Haven’t even put a tape in it. There’s the tape.

(Tape clatters on table)

Dave Cawley: Of course, he neglected to mention his second — hidden — recording device. The one capturing this copy of their conversation.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): If you want to talk about it, I’d, I’ll be glad to work what I can with it. Umm, I made you a promise before if I could get the body back, I would drop the capital aspect of it. Or we would submit it that way. But those were the only terms that I would work with.

Dave Cawley: Doug had refused that earlier offer.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I’m gonna read it to you so you understand it, Doug. It says, the undersigned complaint upon the oath states that the complainant has reason to believe that the above named defendant on or about the 11th day of August, 1985 in Weber County, state of Utah committed—

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Have they they proven she’s even dead?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): —committed a capital felony. To whit, aggravated murder, which is murder in the first degree, and then it gives the codes for it, as amended as follows, said defendant intentionally or knowingly caused the death of Joyce Yost under any of the following circumstances…

Dave Cawley: The circumstances included preventing Joyce from testifying, retaliating against her for testifying and hindering the government’s investigation into her rape.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): This information is based on the information from both myself, Gordon Kaufman and Brad Birch, who are the people that gave me the information.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Who’s Gordon Kaufman?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Gordon Kaufman is the person who she was with on Saturday night. He was one of the last people that saw Joyce alive, ok? That’s why we used his information.

Dave Cawley: And that was just count one. Terry read the other counts: kidnapping for taking Joyce with the intent of terrorizing her and preventing her testimony and burglary for breaking into her apartment with the intent of causing her bodily harm.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): So you’re saying they’ve found Joyce Yost?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I’m not saying that. What I asked was for your cooperation and you refused to give that to me, regardless.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Well I, I don’t know anything about Joyce’s disappearance.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Ok.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I didn’t then and I don’t now.

Dave Cawley: Terry whipped out his pen, signed his name on the summons and provided Doug a carbon copy.

(Sound of pen scratches)

Dave Cawley: The cogs must’ve been turning in Doug’s mind. If police didn’t possess Joyce’s body, what evidence could they have? The only person — other than himself — who knew what’d happened to Joyce was…

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): My concern is, uh, for Rhonda. Can you tell me anything that’s happened to her?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Yep. I’m going after Rhonda right now, Doug. And I can prove her involvement, too.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Involvement in what?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): In the murder and death of Joyce Yost.

Dave Cawley: The two men stared at one another.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Are you saying that I or Rhonda, I or Rhonda, or I took the life of Joyce Yost?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I’m saying you and that Rhonda assisted. That’s what I’m saying.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): That Rhonda insisted in a m—, assisted in a murder?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Assisted you in that.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): You’re saying I killed her.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I am, yes. I sure am, Doug.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): You’re wrong, Carpenter. You’re, you’re dead wrong.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Well, I think things will prove to show otherwise, Doug.

Dave Cawley: Terry said he wished Doug had cooperated when they’d met a year earlier. His refusal would likely cost him his life. Doug seemed unfazed.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I’m telling you I didn’t kill Joyce Yost and Rhonda certainly wasn’t.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): And I’m telling you I don’t believe you and I know that that is not true.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): If you think Rhonda was involved in something, I guess you’re crazy.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I could tell you a whole bunch about it. It’s not gonna do me any good to tell you what I know. I wouldn’t have a warrant for you and I wouldn’t be going to pick up Rhonda if that was not the case.

Dave Cawley: This was, of course, deception on Terry’s part, but it had the intended effect. It watered the seed of Doug’s paranoia, his fear Rhonda might crack.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I know what I know, Doug and, uh—

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Do you, do you got a warrant for Rhonda?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): The time for, the time for blowing smoke is all done. ‘Kay?

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Yeah, it is.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): And I’m not gonna play anymore. Uh, I gave you a long time to do it, so I’m—

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): And to be honest with you, I’m glad it’s here. I’m glad it’s here so we can finally get it out because I’m tired of it being held over me. I honestly I am.

Dave Cawley: The cards were on the table and Doug believed he held a hand that could beat the house.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): If you think I killed Joyce and you think Rhonda was even so much involved in a, a criminal homicide case, you’re umm, you’re wrong.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Well, I don’t think so. And I think without any question I can prove it. So, we’ll be glad to submit it and work with it from there.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Fine. Is that it?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): That’s all have. Yep.

Dave Cawley: They stood…

(Sound of them standing)

Dave Cawley: …and walked out into the hallway. Terry expected to find prison staff there, waiting to take Doug over to Uinta, the prison’s maximum security building. But they weren’t there. Doug took off down the hallway, as if headed back to SSD.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Doug, come back to me here. I don’t think they want you to go anywhere.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Huh?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I don’t think they want you to go anywhere.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Where am I gonna go?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I think they want you to wait right here.

Dave Cawley: Doug did as ordered and, while they stood and waited, lit a cigarette and wished Terry good luck. Terry replied this was a good chance for Doug to consider what he’d done.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): The last time I faced you, I stood eyeball-to-eyeball with you and told you that I’d made arrangements to get you out of jail to take you to your mom’s funeral. Do you remember that?

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Yeah.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): That was true, Doug. That was—

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): And if we would have been on the streets, you would have approached me with that, I would have took your [expletive] head right off.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Well—

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Using my mother like that.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I didn’t use your mother for anything.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Oh, the hell you didn’t.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): That was an opportunity for you, Doug, to be able to get out of here and do something on your own. Otherwise you’d have never got it. And obviously you didn’t get it. Right?

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): If you’d have brought it to me that, that way on the streets—

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Well, if you was on the street, you wouldn’t have had to have any help to get there.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): The way you used my mother like that, that was bull[expletive].

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Well, I didn’t use your mother. You knew about it, you was the one who commented on it.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): You used the death of another person, my mom had just barely died you son of a bitch. We was on the streets Carpenter, I would have took your [expletive] head right off.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Well, that would be welcome, y’know?

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): And I, and I’m not no basket mental case like I was in Joyce’s trial. You guys got a hell of a fight on your hand and I’m glad this is here.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): That’s good. I’m glad it’s here too, Doug. And obviously nothing’s got to you, there’s no conscience involved and that probably tells me basically what I needed to know.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I did not take the life of Joyce Yost. If she is in fact dead, I did not take the life of Joyce Yost. Nor was I there.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Okay.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): And Rhonda was no way, no way involved.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I uh, think that will prove otherwise, Doug.

Dave Cawley: Doug doubled down.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Well, I, y’know, it would have been nice to have gotten to the point where you’d even talk about it or give us what information you did have about it and uh, you obviously didn’t want to do that.

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): What information do you want? I don’t have none.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): That will change.

Dave Cawley: Doug turned and walked away from Terry again. He found a prison guard and asked to go back to SSD.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Okay, whatever. I don’t—

Doug Lovell (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I’ll see you.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Alright, I’ll be there.

Dave Cawley: Terry was not finished, though. He went to find the duty officer as Doug headed across the yard.

Corrections officer (from May 14, 1992 police recording): How’s you doing?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): I’m doing good. I’m doing good. Your inmate’s not doing so good though. I just served capital homicide warrants on him.

Corrections officer (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Oh, I bet he’s not a happy camper.

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): He is pissed.

Corrections officer (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Where’d you put him at?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): He went back. I stood out here in the hall for 15 minutes with him and he walked right back and says, ‘I’m going back to SSD.’

Corrections officer (from May 14, 1992 police recording): (On radio) SSD duty officer. (To Terry) What was his last name again?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Lovell.

Corrections officer (from May 14, 1992 police recording): (On radio) Hey Langley, send uh, Lovell back over here to the building. Yeah. He should be on his way back. Don’t even let him come in the building. Just send him right back over here.

Dave Cawley: Terry had taken the advice of a prison informant named William Babbel, whom you heard in the last episode. William had told Terry the prison would be able to place Doug in maximum security once the murder charge was filed. Terry had arranged to make that happen. Doug was losing his place in SSD, with all its privileges.

The officer-in-charge of the prison that evening was Carl Jacobson, the guard with whom Doug had for so many years watched the 6 o’clock news. Carl had by this point in ’92 promoted to the rank of lieutenant. Carl took the call from the duty officer and headed over to SSD to intercept Doug. Terry Carpenter, meantime, warned prison staff to be cautious.

Corrections officer (from May 14, 1992 police recording): He’s uh, not hostile, is he?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Oh, he’s pretty upset, yeah.

Corrections officer (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Oh, he is?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): He’s pissed.

Corrections officer (from May 14, 1992 police recording): He doesn’t know he’s going to three?

Terry Carpenter (from May 14, 1992 police recording): Nope. Not yet.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Doug’s brother Russ received a collect call from the prison on the evening of Friday, May 15, about 24 hours after Doug’s move out of SSD.

Operator (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): This is US West communications. You have a collect call from ‘Doug.’ Please answer the following question yes or no. Will you pay for the call?

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Yes.

Dave Cawley: But it wasn’t actually Doug on the line.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Hello. Uh, hey uh, I’m a partner of Doug’s, man. They got him in a lockdown situation right now. And uh, he’s over here in Uinta 2. It’s maximum security. Before he was in Uinta 3. And uh, he asked me to call you. … Uh, I don’t know if you’ve heard the news or not.

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Yeah, it’s in the paper. It’s supposed to be on the news in a few minutes.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Yeah, it’s already been on at 5:30 on 4. It should come on 5 at 6 o’clock.

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Uh huh.

Dave Cawley: The man told Russ Doug had an urgent request. He needed his brother to call Rhonda.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Rhonda, yeah. He wants to know how her and the kids are doing. And he says if she isn’t home, please call the Weber County Jail and see if she’s been booked yet or not. They told him they was gonna charge her.

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Oh really?

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Yeah. They told him that yesterday. He says, ‘Well I’m—‘ the detective told him, ‘I’m going up there to arrest your wife now, your ex-wife now.’

Dave Cawley: The man asked Russ if he knew whether or not Rhonda had been arrested.

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Oh, I have no idea.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Uh, could you call and then, if she is—

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Sure.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): And I’ll call back in 30 minutes and you can—

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Okay.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Okay.

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Alright.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Alright then. Thank you for accepting the call.

Dave Cawley: Doug’s friend called Russ again a short time later.

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Hello there.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): How you doing?

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): (Laughs) I talked to Rhonda. She’s, they haven’t, they didn’t pick her up or anything. She has to be to court the same time Doug does I guess Wednesday morning.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Did they go talk to her?

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Yeah.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): And uh, they’re charging her too?

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Well, they haven’t yet.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Mmmhmm. But they’re gonna charge her Wednesday?

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Probably.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Uh huh.

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Well, all she said is she had to be to court Wednesday.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Okay, well he just wanted me to find that out, and—

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Yeah so, she’ll be there, probably when, I guess probably the same time he will.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Okay.

Dave Cawley: The man told Russ his brother wasn’t in a great state of mind.

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Well, that’s the way Rhonda is. Tell him Rhonda’s not very good, either.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Uh huh. Yeah, it’s sort of a complete shock to him, y’know, but, uh, there isn’t too much I can say over the phone so—

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Yeah, okay.

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Okay, I better let you go.

Russ Lovell (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Alright

‘Partner’ (from May 15, 1992 prison phone recording): Alright. Thanks you for accepting the call.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Doug’s move to the prison’s Uinta facility had triggered TRO, or temporary restrictive order. Solitary, in other words. He’d spent hours stewing alone in a cell, wondering what pressure police were then applying to Rhonda. The very first call Doug made when he came out of TRO on Saturday morning was to Rhonda’s phone. She didn’t answer. So, he called his brother Russ.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Hey, have you heard anything?

Russ Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): About?

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Huh?

Russ Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): About what?

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): With Rhonda? How’s she doing?

Russ Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Oh, she’s okay. Well, I mean, she’s not good but, she’s got to be there, oh, to that court thing on Wednesday, too.

Dave Cawley: Doug told Russ he didn’t understand what the police were doing, since neither he nor Rhonda had had anything to do with Joyce Yost’s disappearance.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Uh, they, they still don’t, to my knowledge, have any proof that this woman’s even deceased. Y’know, everybody down here is telling me that they’re bluffing, that there probably ain’t even gonna be any charges. Yet, Doug seemed most concerned about how his ex-wife was responding.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Was Rhonda ever charged?

Russ Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): No, I guess she will be Wednesday.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): See, that’s kind of weird too, don’t you think?

Russ Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Yeah.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): I mean, usually when they have a warrant for someone, especially, what are they going to charge her with?

Russ Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): I don’t know.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Conspiracy to commit?

Russ Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Probably.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): That’s a serious charge. That’s a five-to-life. Y’know, they would have arrested her and took her right downtown. Booked her, questioned her, interrogated her, the whole bit. Doesn’t that seem odd?

Russ Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Yeah.

Dave Cawley: Doug begged Russ to call Rhonda and give her one simple direction.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Y’know, Rhonda’s got nothing to hide and I got nothing to hide but, y’know, you need to get ahold of her, Russ, if you can and tell her not to say anything to anybody at any time.

Dave Cawley: Russ told his baby brother not to worry so much. There was nothing Doug could do about any of it until his arraignment hearing the following Wednesday. Still, Doug couldn’t help but bemoan his situation.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): [Expletive], I’ve lost my job. Y’know? Now, if I win this, they’ve got to reinstate my job and everything but in the meantime they’ve took me from my job, they’ve took me from my facility. I’ve lost everything. I’m sitting here in a [expletive] orange jumpsuit. Looks like I want to go deer hunting. Bright orange jump suit with, with blue floppers. I’ve got nothing over here. They don’t let you smoke over here. God, it’s crazy.

Dave Cawley: Russ suggested maybe Doug should sue the police for harassing him. This made Doug hesitate and he again brought up Rhonda.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Well, listen. I can’t leave a message on Rhonda’s telephone machine. Would you please call, leave a message on her telephone machine and have her call you immediately? When she does call, tell her that everyone down here is telling me that this is bull[expletive]. They probably ain’t even gonna charge us. And, y’know, it, it’s a big bluff thing to see if anybody does know anything to see if they’ll crack or not. Tell her not to say nothing to the police, to nobody.

Russ Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): ‘Kay.

Dave Cawley: Doug had to get in touch with his ex-wife. In the back of his mind was the angry letter he’d sent her at the start of that week. How would she respond to it now? When Rhonda at last answered one of Doug’s calls, the letter was the first thing he wanted to discuss.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Did, did you get my last letter?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Yeah I did.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Well, dis, disregard it for now. I had it coming at a bad timing. I mean uh, I was going through a lot of changes over the kids, Rhonda, but I think right now we need each other. Can we at least have that?

Dave Cawley: Rhonda told Doug she might soon be joining him at the prison.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Rhonda, you didn’t do anything. You didn’t do anything and I didn’t do anything. We got nothing to worry about. Anything they got, some reliable people have told me down here they’re shooting for the stars. They didn’t even arrest you, did they?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): No, but I’m supposed to be in court Wednesday.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Right, doesn’t that seem a little odd that they didn’t arrest you?

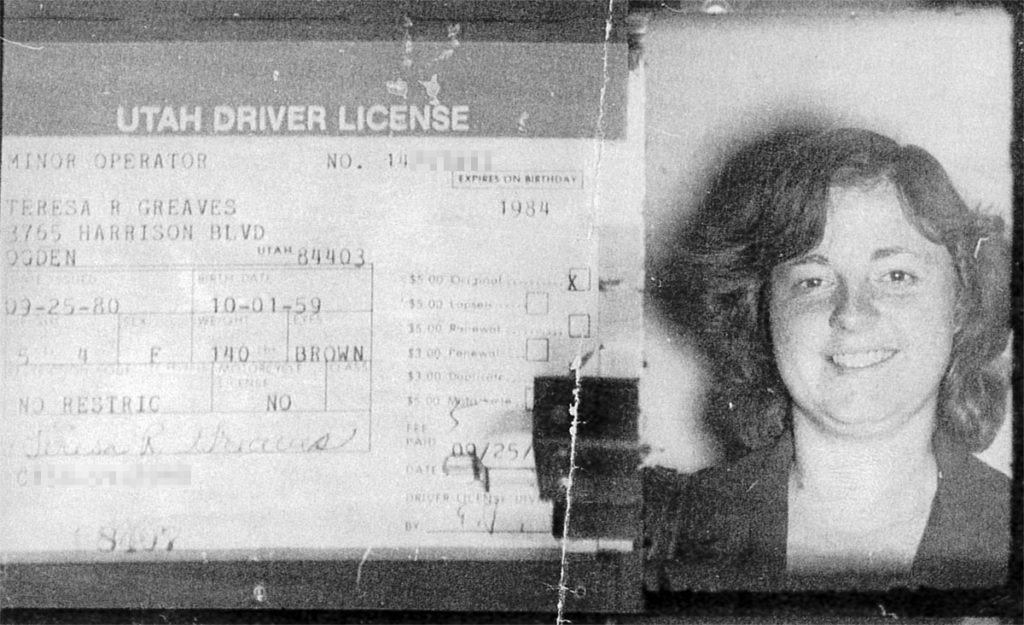

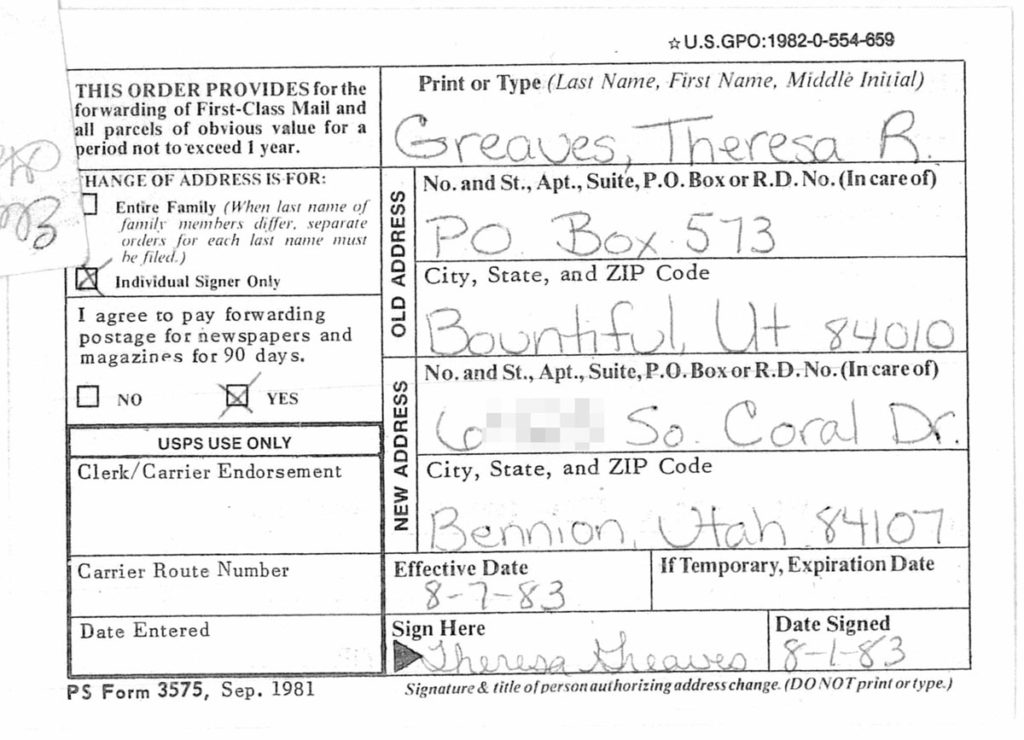

Dave Cawley: Rhonda knew full well why she hadn’t been arrested, but she conjured a different story for Doug. She said maybe detectives hadn’t wanted to haul her away in front of her two kids. Doug reminded Rhonda this was an eventuality they’d always known might come.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): I mean, as soon as we first seen it on the TV, I says, ‘Oh my God, they’re gonna believe that I did it from, from day one. They’re gonna believe that I had something to do with her disappearance.’ So we always kind of knew that there might some [expletive] over it, right?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): I don’t know what we thought, Lovell. I’m sick of this [expletive], okay? I’m sick of it. You’d better do something about it. ‘Cause I’m out here living with the kids and what the [expletive] am I supposed to say?

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): That you didn’t do anything, Rhonda. You didn’t.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): I know I didn’t but I still got to go to court, Doug.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): I know it. But Rhonda, if they don’t have anything—

Rhonda Buttars (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): They got to have something, Doug.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Really?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): They won’t just take us to court because they have nothing better to do.

Dave Cawley: Doug rattled off a list of past news stories about Joyce’s disappearance, noting how none of the supposed breaks in the case had ever amounted to anything. He said he intended to go to arraignment and have his court-appointed lawyer file a discovery motion. That way, he could learn exactly what evidence the police had. Doug told Rhonda he had it under control.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Remember like I did on that poaching thing, Rhonda? I knew what the hell I was doing. I knew exactly what I was doing and I should have done that with John but, y’know, because of my injury to my back, y’know, I was on all those Percodan and Valium and, and stuff. Y’know, I just, I laid down, Rhonda. That’s exactly what I did is I laid down.

Dave Cawley: Doug said even if police arrested Rhonda, they’d have to give her bail. If needed, his dad or brother could arrange a property bond for her, just as they’d done for him after his arrest for rape in April of ’85.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): If in fact Joyce is dead, they’re gonna have a hard time proving that she’s dead. First off, they have to prove that there’s, that there’s a death before they can say that there’s a murder. Don’t you understand that?

Dave Cawley: Doug, it seemed, understood well the concept of corpus delicti. He begged her to trust in him and to trust in the system. Underlying this though was Doug’s actual fear. He toed up to the brink of it, like a person easing over ever-thinning ice on a frozen lake.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Y’know, this has all kind of come about since you and I split up. And, y’know, it kind of makes me wonder. … Not, y’know, not about you but umm, it just, I don’t know. It makes me wonder about a few things. … I hope you’ll fight this with me, Rhonda. And I, I just ask that you please trust my judgement. I, I won’t let anything happen to you.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda told Doug she didn’t want to hear it. He wasn’t in control. He couldn’t protect her.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): I need you Rhonda. I think we need each other.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): I’m gonna go, okay?

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Honey?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Don’t give me that, okay? I can see right through it, Doug. I’m going. I’m going now.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Please don’t hang up on me.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): I’m gonna go. I’m not hanging up. I’m saying goodbye.

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Rhonda—

Rhonda Buttars (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): What?

Doug Lovell (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): Please, please don’t leave me like this.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 16, 1992 prison phone recording): I don’t want to talk anymore, Doug.

Dave Cawley: If Doug’d had doubts about Rhonda’s loyalty before that call, they could have only grown more ominous afterward.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: Doug called Rhonda again the following day, on Sunday, one week after writing her the angry letter. Rhonda told him she wasn’t feeling well.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Well I feel a little better today than I did yesterday. I had a lot of time to think. That’s all you got to do over here is think. Right now nothing to do. Think or fight. Take your pick. Rhonda, I don’t know how things are going to turn out but I want you to know and, uh, and have faith that I will do the right thing. Y’know, when the time comes. Y’know? Let’s see what happens and y’know see what kind of cards are dealt to us.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda didn’t say much, even as Doug peppered her with more questions. What time was she supposed to be to court? Had the police given her a list of charges? Did they leave her any papers?

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): And it’s extremely odd how they did it to you. I mean, if they want to charge us, they would come up and say, ‘Mrs. Buttars—’

Rhonda Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): I ain’t no Mrs.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Well, ‘Ms. Buttars, we’re South Ogden police department. You know who we are. We have a warrant for your arrest. Uh, would you please, uh, turn around put your hands behind your, put your hands behind your back.’ You’d do that. They’d probably have a lady officer with them. They would take you down to court. They would book you, fingerprint you, take your mugshot and then they’d question you, ask you if you want an attorney. They’d read you your rights. They never did none of that. That’s why I, I question the whole thing. And I’m not saying they won’t charge us.

Dave Cawley: But, Doug said, the odds of a conviction were very low.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): I mean, there’s probably 10 people in all of America that’ve ever been convicted on a, on a homicide charge without first proving that there’s been a murder. Y’know, a body. I mean, it’s extremely rare. It’s never been done in Utah, not on a capital homicide. It’s never been done in Utah.

Dave Cawley: That number’s not quite right. There have obviously been more than 10 no-body homicide convictions in the United States. But Doug was correct that no-body capital homicide convictions — which qualify for the death penalty — were and are rare. Rhonda was not much interested in this bit of trivia. So Doug pivoted, making an emotional appeal.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): I miss you, Rhonda. I miss everything we had. And I’m sorry I blew it. I really am. I mean, I can’t believe what direction I have sent my life in. I just can’t believe it.

Dave Cawley: He apologized for acting selfish, for spending their money, for causing her unhappiness. Rhonda bit her tongue.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Is there anything you want to say to me?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): No.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Nothing at all?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Hmmnmm.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): I wish we hadn’t grown apart. Do you ever regret that?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): What?

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Uh, growing apart the way we have.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): No. You’re the one that did it, not me.

Dave Cawley: Standing on sentiment was not a strong play for Doug.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Do you just want to go?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Yeah.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): You’re sure not too talkative with me, honey.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): I don’t feel good. Did you forget that part?

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): No.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Oh.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): I feel extra bad when you don’t feel good ‘cause I know what you like. And I can be that. I can very easily be that. Do you believe that?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): No.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): You ain’t gonna give me a glimpse of hope, are you?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Mmmnmm.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): You’re not gonna let even a little bit of light in, huh?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): You had your chance.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): And that’s, that’s it, for life, forever, for eternity?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Hah.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Huh?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Hmm.

Doug Lovell (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Sounded like a perfume for a minute, didn’t it?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 17, 1992 phone recording): Yep.

Dave Cawley: Doug concluded this call by telling Rhonda no matter what, he would do the right thing in the future. The next morning, he came out of his cell for breakfast just in time to witness a brawl. He told his brother Russ about it on the phone.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): Boy, they got one of these sections down here, [expletive], right at breakfast, man, a big old fist fight. [Expletive]. Y’know, like I gotta get up and go through this [expletive]. It’s crazy, man, it’s crazy. [Expletive], there’s been probably a half-dozen fist fights just, just since I’ve been over here. Since Thursday.

Russ Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): Really?

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): It’s bizarre.

Dave Cawley: Doug vented to his brother about how much worse life was in the Uinta facility compared to SSD. He figured it wouldn’t be long before he could force the prison to send him back.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): ‘Cause technically I’ve done nothing wrong, to be moved. I’ve done nothing in the institution to be moved. And technically right now they have to keep my job for me and they have to keep my spot at SSD. So, you know, I’m not too worried about all that. Because as long as I’m moved for court reasons or health reasons or something, something that has nothing to do with something that I’ve done since I’ve been in here, you know, they can’t uh, they can’t do anything. So all that’s still good, but y’know, how long that’ll be good, I don’t know. I mean, I hope this ain’t even gonna go to a preliminary hearing.

Russ Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): Oh yeah.

Dave Cawley: Of course, the real motive for Doug’s call was to make sure his brother would be at the arraignment hearing the next day, to support Rhonda.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): To be honest with you, I’m not worried about it because I know I wasn’t involved in anything like that. And I know Rhonda wasn’t. But, you know, if they’re going to try to attack Rhonda, y’know, I don’t want my children’s lives disrupted. That’s what it boils down to. Y’know, and Rhonda doesn’t deserve to go through this. You know what I mean?

Russ Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): Yeah, oh yeah.

Dave Cawley: Doug suggested if Rhonda were arrested at the arraignment, Russ and their dad, Monan, should put up a property bond to cover her bail.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): Like, you know, when dad put that $25,000 for me. He didn’t lose a thing. I mean, there’s no way I’d skip out on you or dad and I know she wouldn’t. [Expletive], she’s got nowhere to go. She ain’t even got a relative that lives out of the state. And Rhonda wouldn’t do that anyway.

Dave Cawley: Russ said he wasn’t sure why they should be on the hook for Rhonda’s bail instead of her own family. And he said he didn’t understand why police would arrest her anyhow, considering she wasn’t involved in any crime. Doug told Russ it was all a ruse. The police couldn’t have anything on him, because of course, he hadn’t done anything. Neither had Rhonda. And, he said, it’d been seven years.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): I can’t believe that after all this time, Russ, they’re, they’re trying to pull something.

Russ Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): Well, see we’ve got this kid out at work that we’d always thought he’d killed his wife a long time ago. And uh, they just charged him with it. His name’s Wetzel.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): Never heard of him.

Russ Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): And that, goll. That was back in, oh man, that was back in, oh man, that was long before you was locked up and they just charged him with that this year.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): No [expletive]?

Russ Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): Yeah. Jon Wetzel’s the name.

Dave Cawley: Jon T. Wetzel. Let me pause here and tell you a bit about the Jon Wetzel case. Like Doug, Jon Wetzel hailed from the Ogden area of Utah. His estranged wife, Sharol Wetzel, had served him with divorce papers on November 13, 1985. A week later, Sharol turned up dead, having been shot once in the head and left in her car parked near the Ogden River.

A month later, around the same time Doug was standing trial for the rape of Joyce Yost, Jon Wetzel’s girlfriend Kittie Eakes was pleading guilty to murder. She admitted to the crime but said she’d acted alone. She refused to implicate her lover in his estranged wife’s execution.

Kittie headed to prison in January of ’86, just like Doug. And like Doug, she entered therapy once there. It took a few years, but Kittie ended up telling the full story of Sharol’s murder to an attorney she met through Alcoholics Anonymous.

With that, let’s go back to Doug’s phone call with his brother Russ.

Russ Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): Well, this one lady, they found his wife dead in a car somewhere and this one lady that Jon knew I guess took the rap for it. Now all the sudden she’s sitting crying the blues and ratting on him. So I don’t know.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): Hmm.

Russ Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): The papers just didn’t have a lot on it.

Dave Cawley: Weber County prosecutors — the same ones who were charging Doug with capital homicide — had also filed a capital homicide charge against Jon Wetzel just a few months prior. Kittie would eventually testify against Jon, saying he’d hounded her for weeks to kill Sharon, to prevent her from taking his assets in the divorce. Jon had told Kittie when and how to do it. He’d given her drugs, as well as the money she’d need to buy a gun. Kittie had gone along and even taken the fall for it, she said, because she was in love with Jon.

The parallels to Doug’s situation were striking. The timelines of the two cases were almost identical. Both involved a sort of murder-for-hire plot, an abandoned car and a female victim who’d held a position of power over a man.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 prison phone recording): God, and I know I was going to win my appeal, Russ, too. I mean, it would have took probably 18 months to two years but I know I was gonna win that. As soon as that hit the feds, they were gonna throw that thing up in the air and say, ‘Bull[expletive.’ Y’know? ‘You can’t [expletive] do this.’ Because there was so many points, man, we was gonna get them on. That I would have won on. I know it. And I don’t know if this has triggered something or what but it seems like every time my case gets in court they pull some [expletive].

Dave Cawley: Doug finished the conversation by once again imploring Russ to protect Rhonda. To post her bail, if necessary. Later that afternoon, Doug made one final call to his ex-wife ahead of the arraignment. He struck a different tone this time, as if nothing were wrong.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): How’s my kids?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): My kids are fine.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Huh?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): My kids are fine. Two can play that game.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): It’s a joke. Please take it as a joke.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda was not laughing.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): I’ll uh, well hopefully I’ll see you tomorrow.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): I’m sure you will.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): I’ll probably be, like, handcuffed. Uh, can I get a hug?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): From me?

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Yeah.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): You’re pretty brave asking that.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Is that a possibility?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): I doubt it.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Really?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Put me through more changes Lovell than anybody I know.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): What if it’ll bring us together someday.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): I doubt it. It brought us apart.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Yeah, I know but all, through it all I wonder if it will maybe bond our relationship.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Well, don’t count on it.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Well, you never know.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Yeah, I do.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Miracles do happen.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Yeah, they do.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): I think, I think maybe if I work my butt off, what do you think?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Nope.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): You think no way for us?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): No way.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Why, hon?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): ‘Cause you put me through a lot of [expletive], Doug.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Rhonda, people can change. People can honestly, sincerely change.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Well, you haven’t to me. If you’d changed, you’d be doing something right now and you ain’t doing [expletive]. It’s pissing me off. So, you haven’t changed a bit in my eyes, Lovell.

Dave Cawley: Doug complained Rhonda she wasn’t making his life any easier. She scoffed.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): My life’s hell, Lovell. Hell.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Mine is too.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Then do something.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Oh, that’ll make it easier?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Yep.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): For me?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Yep.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Really?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Yep.

Dave Cawley: A long pause. Rhonda lit a cigarette. Its smoke hung in the air, along with all the unspoken context behind her words.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Whether you believe me or not, Rhonda, I do love you. I have always loved you. And I, and I do care more than any person’s ever cared about you. I’ve just had an odd way of showing it.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Yeah. (Laughs) I’d say.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Please don’t laugh at me. I’m serious.

Dave Cawley: Doug promised one day, he’d have an opportunity to “completely blow” her away.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): I know that I, I can give you the life that you deserve and the children the happiness that they need and deserve.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Doug, give up.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): I’m serious, Rhonda.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): I know you are. So am I.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Well, you, hey. You can fight it all you want.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): (Laughs) I’m not fighting.

Dave Cawley: Doug had to go. It was time for count and he had to go back to his cell. He told Rhonda he would see her in the morning.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Well uh, remember I’ll be thinking about you.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): ‘Kay.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Just remember, be strong, Rhonda. You got nothing to worry about. You didn’t do anything. Ok?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): ‘Kay.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Give my love to the kids.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): I will.

Doug Lovell (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Bye bye.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 18, 1992 phone recording): Bye.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Doug arrived at the Weber County courthouse on the morning of May 20, 1992 for his circuit court arraignment. He was assigned a court-appointed defense attorney, a guy named John Caine. John’s name might sound familiar. That’s because John was the same lawyer who’d represented Doug 14 years earlier, during his 1978 trial for armed robbery.

The prosecutors assigned to the case were the county attorney Reed Richards, who coincidentally happened to be John Caine’s old law partner and whose father Maurice Richards also represented Doug in the ’78 robbery case, as well as a man named Bill Daines.

I know that’s a lot to keep track of, so let’s just focus for the moment on Bill Daines. Joyce’s son-in-law, Randy Salazar, told me he remembered first meeting Bill sometime around Pioneer Day. That’s a state holiday in Utah, celebrated each July 24th with parades and rodeos. Bill had entered the room dressed not in a suit, but instead in denim pants and a cowboy hat.

Randy Salazar: And I seen how he put his hands on the desk and just kind of talked to us and I just thought ‘Geez, I hope this guy…’ But I tell you what, that dude knew his… In fact, he was giving us dates and times and I was thinking ‘damn, you guys are going to do your job. You guys are going to do well with your job.’”

Dave Cawley: The first real courtroom clash between these two sides came not at the circuit court arraignment, but instead at a preliminary hearing on July 28. That’s when the prosecution put Rhonda on the stand. At that moment, Doug knew for certain who had betrayed him.

Terry Carpenter: She told me about the night that she’d taken Doug up there…

Dave Cawley: It was the same account she’d given to Terry Carpenter.

Terry Carpenter: And that he’d laid in the bushes across the street from Joyce’s house and waited for her to come home.

Randy Salazar: Can you believe she drove him up there? And then picked him up? What kind of person is that?

Dave Cawley: Joyce’s son-in-law Randy Salazar sat, stunned at what he was hearing.

Randy Salazar: Y’know, you think to yourself, ‘How the hell do you think this didn’t happen? How is this lady telling this story,’ y’know? ‘How are you still with this man? Why are you sticking up for him? What kind of lady are you?

Dave Cawley: At one point, Doug bolted upright.

“That’s a lie, Rhonda,” he shouted. “You know that’s a lie.”

The judge, Parley Baldwin, told Doug to take his seat.

“Your honor, she is lying,” Doug said.

Baldwin again instructed Doug to be quiet, or else the bailiffs would remove him from the courtroom. Doug flung a curse word or two at Rhonda as the bailiffs approached.

“Sit down, [expletive] [expletive],” Doug said to them.

Terry Carpenter: He could let you believe that he was telling you the truth and emotional about it and the next second he was angry and mad and no remorse whatsoever.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda had told Terry she feared Doug. His courtroom outburst only emphasized that. Joyce’s son Greg Roberts told me over time, he’s come to feel sympathy for Rhonda.

Greg Roberts: Somewhere along the way I’ve forgiven her. I think Kim would rather see her pay a penalty for what happened, but I think that she was under the huge influence of this psychopath and she, she was in some sort of a fog that she, those options weren’t real for her.

Kim Salazar: My whole thing with her is that she is in my mind the one person that could have stopped it that night. She held all the cards. And I get fear. I understand fear. But my mom literally lived across the street from the police station. She could have dropped him off. She could have gone straight to the police station. And before he had a chance to do anything, they could have been there. And he’d have been locked up for a long time. She didn’t have anything to be scared of.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda’s testimony was more than enough to allow the judge to determine probable cause existed to proceed. He concluded the hearing by sending the case to the district court where, a month later, Doug pleaded not guilty to the charges. The district court judge, Stanton Taylor, scheduled a jury trial to begin on February 2, 1993.

[Scene transition]

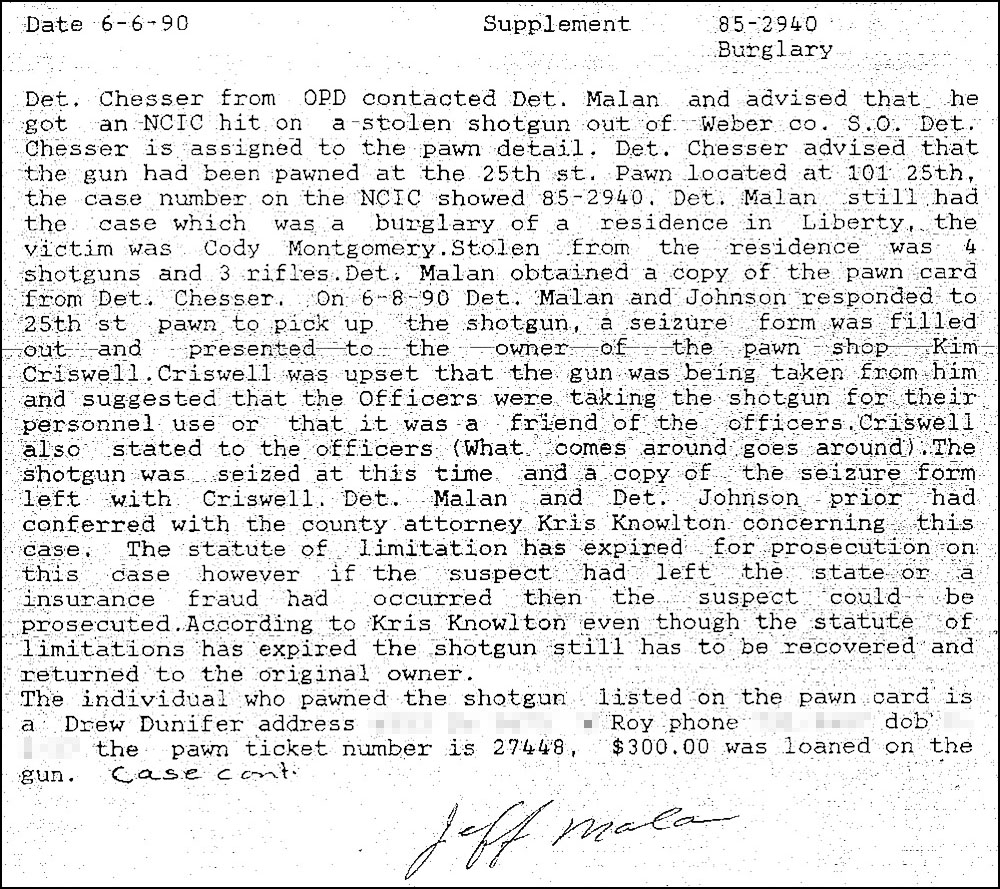

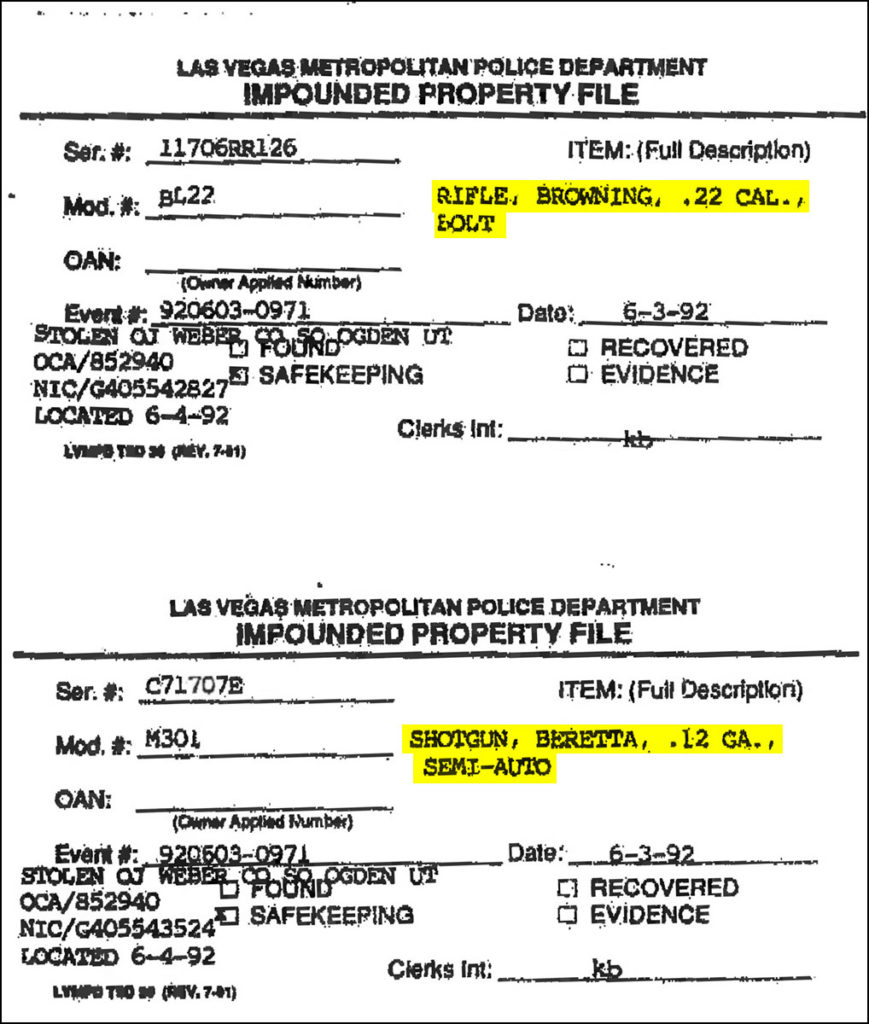

Dave Cawley: Several weeks before the preliminary hearing I just described, Doug’s friend Ron Barney met with a Las Vegas Metro Police detective in Nevada. Ron had something to turn over to the police. Two somethings, actually: a Browning model BL22 bolt-action rifle and a Beretta M301 12-gauge shotgun. The serial numbers for both guns were listed in NCIC, the FBI’s national crime information database, as having been stolen out of Weber County, Utah on May 5, 1985. They were two of the guns taken from the home of Cody Montgomery, Sr. by Doug Lovell and Billy Jack.

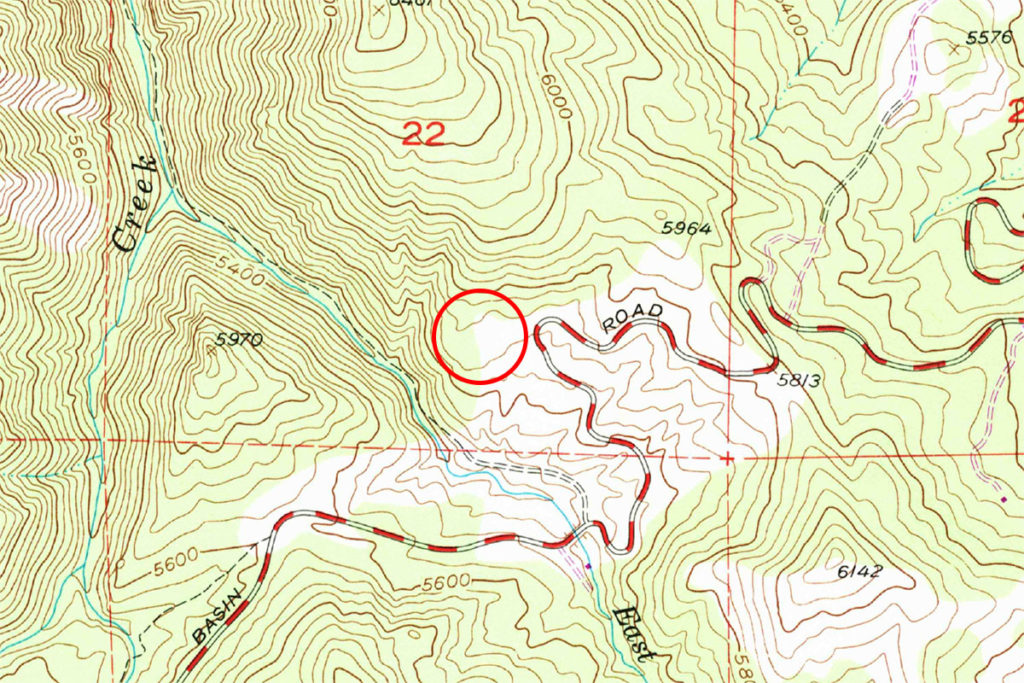

Terry Carpenter: The guns went to Callao, where they were buried.

Dave Cawley: Terry Carpenter had at long last linked the stolen guns to Doug Lovell. He’d also tracked down Billy Jack in Colorado, interviewed him and in the process discovered evidence corroborating Rhonda’s account of the Mother’s Day weekend outing when they’d buried the guns.

Terry Carpenter: Coming back home, they pull off to the side of the road and have to take a leak, to be blunt. And a trooper stops and catches them at the side of the road and we’re able to verify that that happens and who they are.

Dave Cawley: But how then had the guns ended up in the hands of Doug’s old hunting buddy Ron Barney?

(Phone ringing sound)

Dave Cawley: I called him to ask that question.

Ron Barney (from May 12, 2020 phone recording): Hello, this is Ron.

Dave Cawley (from May 12, 2020 phone recording): Hey Ron, my name is uh, Dave Cawley. I’m with uh KSL, uh radio up here in Salt Lake City, Utah. Do have a sec?

Ron Barney (from May 12, 2020 phone recording): Yep.

Dave Cawley: At the time of this phone call in May of 2020, I knew quite a bit about the history of these guns.

Dave Cawley (from May 12, 2020 phone recording): I’m trying to figure out how they ended up down there with you. Can you help illuminate that for me?

Ron Barney (from May 12, 2020 phone recording): Uh no, I really can’t. I can’t remember exactly how that went by.

Dave Cawley: I knew they’d surfaced in October of ’85 when somebody had inquired about pawning them at place in Ogden called the Gift House. I described that back in episode 4. Ron Barney at that time resided in Utah’s Salt Lake Valley. He didn’t move to Logandale, Nevada until sometime after 1988. I knew Terry Carpenter had paid Ron a visit in Logandale in May of ’91. I described that in episode 6.

Ron Barney (from May 12, 2020 phone recording): Was that, Carpenter. Was that the detective’s name that came down to Las Vegas?

Dave Cawley (from May 12, 2020 phone recording): Yep, that’s the guy.

Ron Barney (from May 12, 2020 phone recording): Yeah.

Dave Cawley: Terry had asked Ron what he knew about the stolen guns. Ron had declined to disclose at that time he possessed two of them. He hadn’t conceded that fact until Terry had made a second trip to Nevada to apply additional pressure.

Terry Carpenter: And he denied up and down and we finally says ‘well, we’ll give you so long and then if we have to charge you, we’ll charge you with possession.’ And then he cooperated.

Dave Cawley: And so that’s why Ron had surrendered the guns to Las Vegas Metro police in 1992.

Terry Carpenter: No charges were ever filed against him and the guns surfaced, anyway.

Dave Cawley: My conversation with Ron didn’t last long. He told me he didn’t want to discuss his friendship with Doug, saying he’d only known him through having gone hunting together. He considered that relationship part of his past, a past he did not want to relive.

Ron Barney (from May 12, 2020 phone recording): Okay.

Dave Cawley (from May 12, 2020 phone recording): Alright.

Ron Barney (from May 12, 2020 phone recording): Good luck with your uh, your uh, research.

Ron Barney (from May 12, 2020 phone recording): Thank you Ron, appreciate your time.

Dave Cawley: Terry’s recovery of these two guns provided further evidence of Rhonda’s honesty. And they would be a compelling piece of evidence to show a jury, hinting at Doug’s intent to kill.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Defense attorney John Caine had a lot of work to do and not much time to do it. With just months to go before the scheduled trial, John attacked the prosecution’s case first by challenging the kidnapping and burglary counts, arguing the statute of limitations on them had expired. He also filed a motion to suppress the evidence gathered from the two wire recordings of Rhonda at the prison…

Doug Lovell (from January 18, 1992 wire recording): If I would have been mentally together, physically together, I wouldn’t be here. They’ll never convict me if I go back to court. There’s no way.

Dave Cawley: …as well as Rhonda’s damaging testimony from the preliminary hearing.

Autumn turned to winter. Subpoenas went out, ordering the investigators, Joyce’s family, Rhonda and the other potential witnesses to all appear at the February trial. With just a week and a half to go, Judge Taylor issued an order rejecting the motion to suppress. Rhonda’s testimony and the wire recordings, he said, were fair game.

John Caine immediately asked that the trial be delayed while he appealed that decision. He would ask the Utah Supreme Court to block the use of Rhonda’s testimony and the wire tapes. Judge Taylor agreed to the delay. The trial was placed on hold.

John told Doug if they won this appeal, he stood a very good chance of also winning the entire case. If the appeal failed, however, John warned his client they would get “hammered.” Everything hinged on Rhonda. John also started talking to the county attorney, his old friend Reed Richards. They were frank with one another. Reed said the only leverage Doug had was that Joyce’s children Kim Salazar and Greg Roberts wanted her body returned.

Greg Roberts: We definitely were willing to compromise if he really gave us her body.

Dave Cawley: And so, Reed said he was willing to take the death penalty off the table if Doug would return Joyce’s remains. It wasn’t a formal offer, more of a testing of the water. John didn’t want to commit before discussing it with Doug, so he went to the prison for a face-to-face. He posed the question: would Doug be willing to plead guilty in exchange for a sentence of life with the possibility of parole? Doug said yes. John needed more assurance. He didn’t want to get down the road with the negotiation and have it fall apart because Doug couldn’t deliver.

He asked could Doug really locate the body, given all the time that had passed? Doug said he could find it in the dark. In fact, he was willing to go do it right that moment. John reminded him it was the middle of winter. Doug told his attorney that didn’t matter. He’d be able to find Joyce’s body even in a blinding snowstorm.