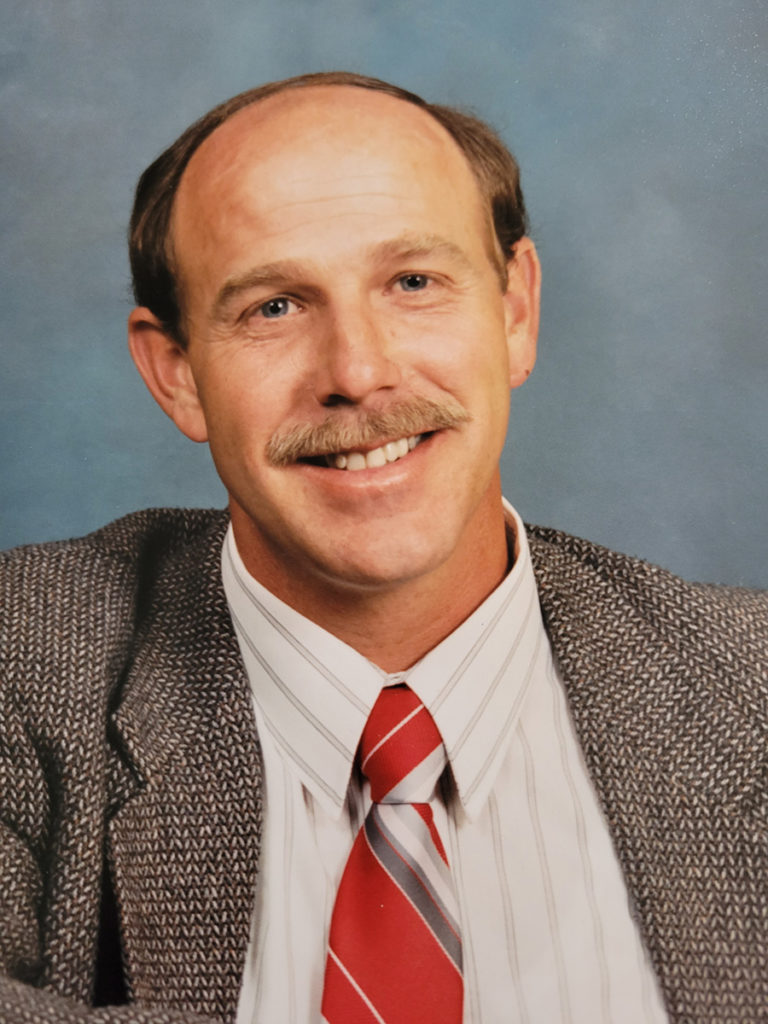

Dave Cawley: South Ogden police sergeant Terry Carpenter drove into downtown Ogden on the afternoon of April 10, 1991. He headed to a building on Washington Boulevard, which housed the offices of the Utah Department of Social Services. The offices where Doug Lovell’s ex-wife Rhonda worked.

Terry Carpenter: Kind of out of the clear blue went into work one day … and said ‘Rhonda, y’know, let’s level with each other.’

Dave Cawley: Terry saying this came out of the “clear blue” was perhaps an oversimplification. So let’s back up just a step. Terry was at that time in the spring of ’91 pursuing a longshot lead in the Joyce Yost case. It centered on a claim Joyce had died at the hands of a satanic coven. This tip had come from a woman named Barbara, as I described in the last episode. In this next clip, you’ll hear Barbara say she knew a contract had been put out on Joyce by a guy named “Love.”

Barbara (from April 1991 police recording): I was told that she, that there had been a contract and that her name was Joyce Yost and that I shouldn’t tell anyone or it would be pretty serious trouble.

Dave Cawley: Terry had spent weeks trying to verify this. He’d scoured a gravel pit, searching for bones. He’d told Barbara her information was the most valuable and pressing available in the case. There were no other leads.

Terry Carpenter (from March, 1991 police recording): If I had other leads that were more valuable and more pressing, those would be the areas I’d be concentrating on. Do you think I would have set on this group that you’re involved with for the last several weeks if I had something better that I had to work on? I don’t. This is the most prominent thing that is here right now and it’s very realistic and it’s very feasible.

Dave Cawley: But in truth, the coven lead was fast turning into a dead-end. Which is part of what prompted Terry’s impromptu visit to Rhonda’s work.

Terry Carpenter: You talk to both of them hoping at some point they may cross or that there might be some ties there or that there might be some indication that yes, Barbara’s telling you the absolute truth.

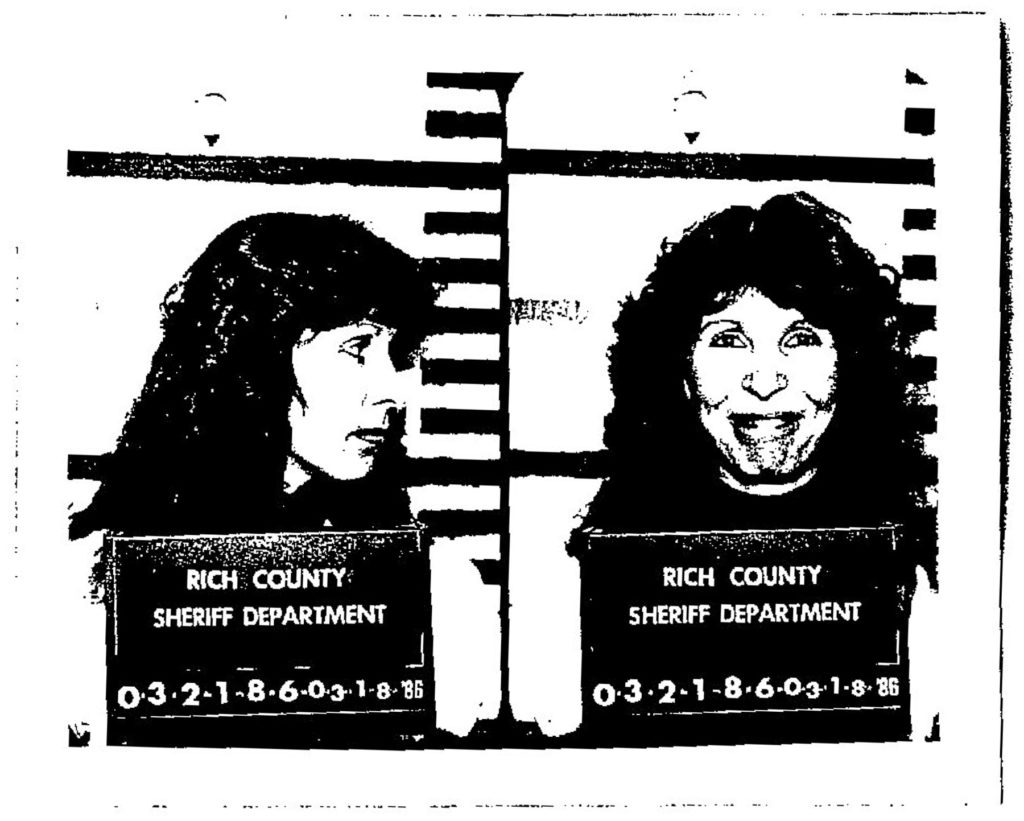

Dave Cawley: Rhonda and Terry sat down in the office break room. She told Terry about her divorce. They reminisced about the time — five years earlier — when Terry had taken Rhonda to jail on the poaching warrant. Her story of that poaching situation had evolved somewhat in the time since. She now told Terry Doug had gone up to Monte Cristo the night before their encounter with the wildlife officer and shot two deer. He’d wanted to retrieve the antlers, so he’d dragged her up there the next day for that purpose.

Rhonda insisted again, as she had before, she had no knowledge of what’d happened to Joyce Yost. Terry fixed her with a stare. Then, he said…

Terry Carpenter: ‘We know that Doug killed Joyce. We know that you’re involved. We know that you helped him, to some extent. And provided that you didn’t pull the trigger, we can get you immunity.’ And she says ‘oh, he didn’t shoot her. He just stomped on her throat.’ And then she went ‘oh,’ like ‘I really blew it.’

Dave Cawley: This was not at all the break Terry might’ve expected. He had sudden clarity. The story Barbara had told about the coven was in no way true.

Terry Carpenter: She thinks Joyce Yost was killed by her dad and the coven and just didn’t happen.

Dave Cawley: It didn’t happen because Doug had killed Joyce himself. Rhonda had kept that secret for years. It’d gnawed at her. Ever since her divorce, she’d considered coming forward. But how could she do that without ending up in prison herself?

Terry Carpenter: And she almost immediately started to cry. And I says, ‘Rhonda, we can help you.’

Dave Cawley: Terry repeated his promise. He would do everything he could to secure immunity.

Terry Carpenter: And so we talked, and we talked and we talked and she got 2,000 pounds off of her chest.

Dave Cawley: Terry’s breakthrough with Rhonda had not come by way of intimidation, technology or clever tactics. It’d simply resulted from his offer of empathy and her willingness to trust.

Terry Carpenter: She’s (sighs) I mean, she’s, y’know I’ve interviewed hundreds of people and know she’s cleaning her soul. She’s telling me what the truth is.

Dave Cawley: That was no small step on Rhonda’s part. She knew what Doug’d done to the last woman who’d crossed him. Terry promised not to let that happen again.

This is Cold, season 2, episode 6: Here We Are. From KSL Podcasts, I’ve Dave Cawley. We’ll be right back.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: Terry Carpenter had knocked the frost off the cold case of Joyce Yost’s disappearance. He took his breakthrough to the Weber County Attorney the day after his meeting with Rhonda Buttars.

Terry Carpenter: They’re excited. They’re finally willing to say we’ve got enough evidence now to go forward. But they still have to prove it.

Dave Cawley: That was complicated by the fact Rhonda and Doug had been husband and wife at the time of the Joyce’s murder. Utah law provided Rhonda spousal privilege, which meant…

Terry Carpenter: We can’t compel her to testify. She has to do that of her own free will.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda I should mention, did not respond to an interview request for this podcast. Neither did her children. But Rhonda showed her free will by meeting with Terry again on the evening of May 1, 1991, for an on-the-record interview.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Has anyone pressured you into doing this, Rhonda?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): No.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Have I made any threats against you?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): No.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Or promises to you, except the immunity?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): No promises except immunity.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Okay.

Dave Cawley: They went step-by-step through the events of the night Joyce Yost died. Rhonda described driving Doug over to Joyce’s apartment in her blue Pontiac 1000 hatchback sometime between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m. Her daughter Alisha, then four years old, had been in the back seat, asleep.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Can you tell me why you dropped him off?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): ‘Cause his intentions were he was going to break in Joyce’s apartment to kill her.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): ‘Kay. Did he tell you that?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Yes.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): You knew that that’s what he had planned to do.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Yes.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda said she and Doug had been there before. She’d taken her husband by Joyce’s apartment at least twice during the summer of ’85. He’d discovered the broken lock on window during one of those visits. On the night of the murder, Rhonda said she’d driven east on 40th Street to the intersection with Evelyn Road. She’d flipped around and come to a stop about 350 feet up the street from Joyce’s apartment. Doug had popped open the passenger door and stepped out into the dark, telling Rhonda he would call her later. So, Rhonda went home. She put Alisha to bed, then went to sleep herself. Her phone rang hours later. Rhonda said it was probably sometime between 4 and 5 a.m. She answered. It was Doug. He told her he was “in the canyon.”

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): ‘Kay. Is that what he told you? ‘I’m in the canyon.’

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Mmmhmm.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): You remember that?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Yes. Because he said, ‘I’m in the canyon and by the time you get to the Wilshire,’ you know, ‘I’ll be there. We’ll probably meet there at the same time.’ And he said ‘I want you to follow me so I can ditch the car.’

Dave Cawley: The Wilshire Theater was a three-screen movie house, a kind of old community landmark in South Ogden, right on the main drag of Harrison Boulevard. The Wilshire was only two miles away from Doug and Rhonda’s apartment.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): But, okay, and then like I got dressed. Got my little girl, put her in the car and went to the Wilshire and he was already at the Wilshire, in the parking lot waitin’ for me. And so I pulled up to him—

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): What was he driving?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Joyce’s car.

Dave Cawley: Doug had a nylon stocking pulled over his hair and was wearing gloves.

“What took you so long,” he asked. “I beat you here and I came clear from the canyon.”

Doug ordered Rhonda to follow him. He started east, through a quiet neighborhood at the foot of the Wasatch Mountains, headed up the hill. Rhonda followed the red glow of taillights up Combe Road to Melanie Lane. The street climbed until it could go up no more. They were at the edge of the city. Nothing above it but mountain: 4,000 vertical feet of scrub oak and scree.

Rhonda parked her car and waited while Doug steered Joyce’s car off of the asphalt onto a dirt track that disappeared into the brush. The track, out of sight of the road, climbed up to a squat water tank.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): He drove up by the water tower and I stayed on the road and waited for him to come down.

Dave Cawley: A car went past, leaving Rhonda to wonder what she’d say if anyone stopped to ask her what she was doing there. But that car didn’t stop. When Doug returned, he was on foot and carrying a large blue suitcase. He stuffed that into the back of the Pontiac before settling into the passenger seat. He instructed Rhonda to head back down to Highway 89 and go south. Rhonda noted her husband seemed a little nervous, but not much, considering what he’d just done. And yes, he told her the story as she drove.

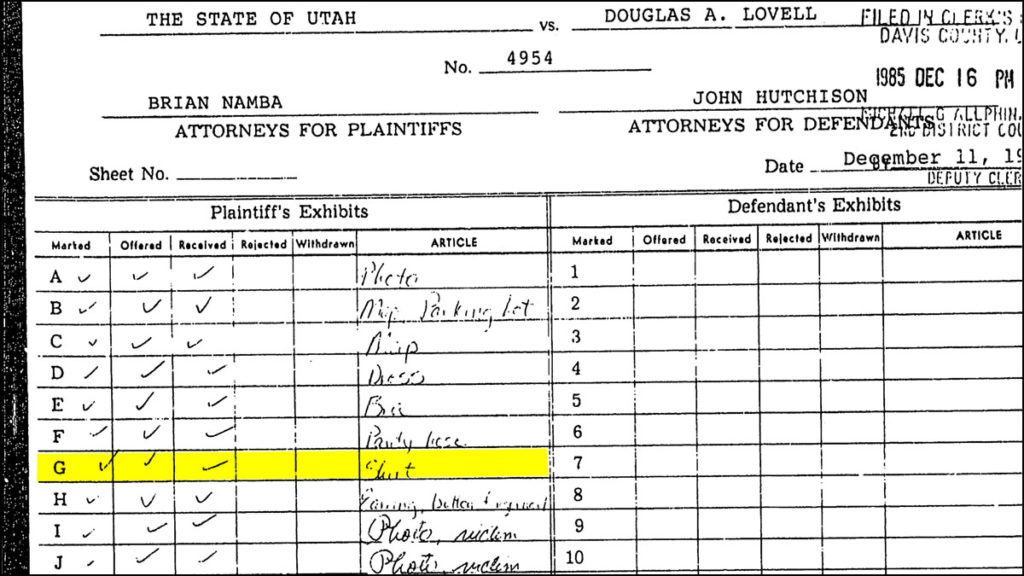

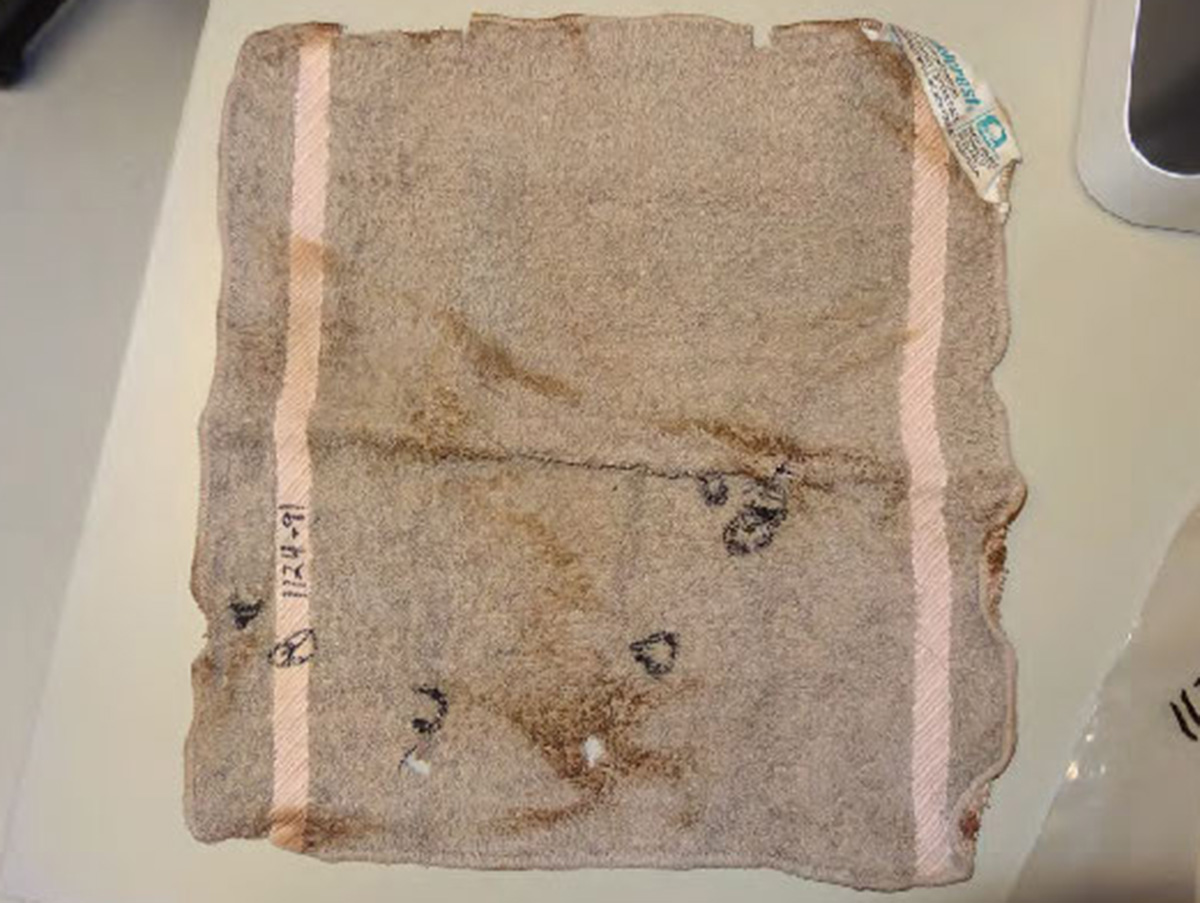

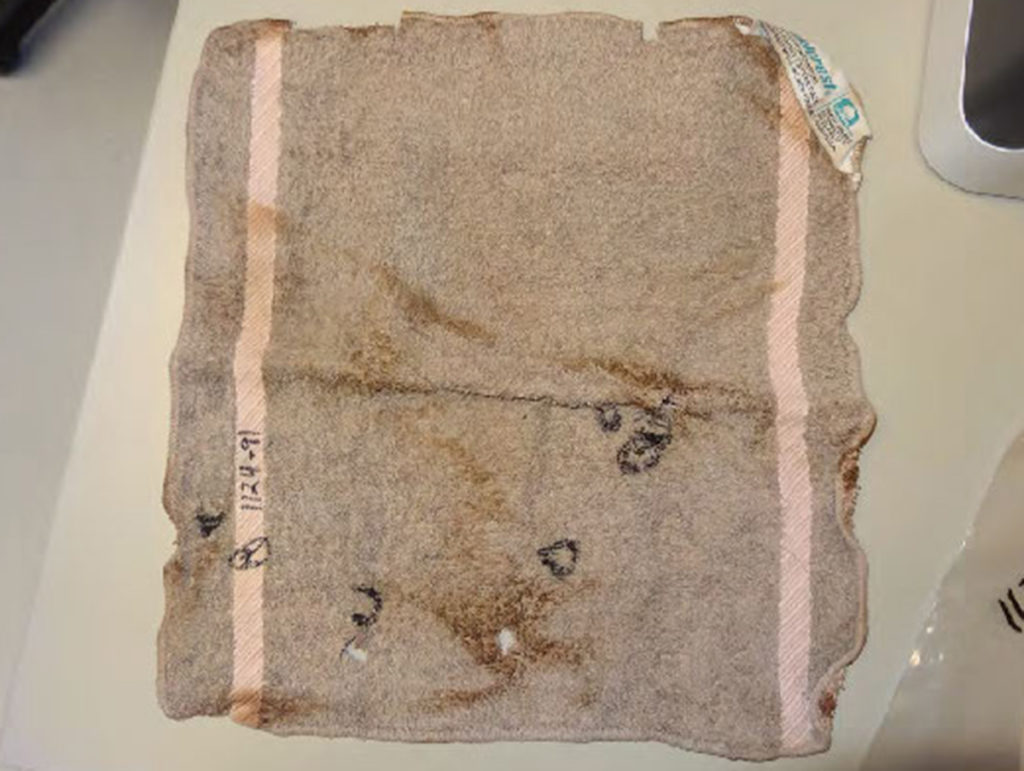

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): He said he broke in the apartment and she was laying on her bed and she was asleep. And it was, I think he said the TV was on and a light was on. It was like she fell asleep watching TV and he said he had a knife with him and when he and went to reach over to grab her by the mouth, so she wouldn’t scream that he cut her hand. And so, umm, he said he got her up and he was, umm, washing her hand and trying to get all the evidence and the blood and everything, so no one would know that she had been bleeding.

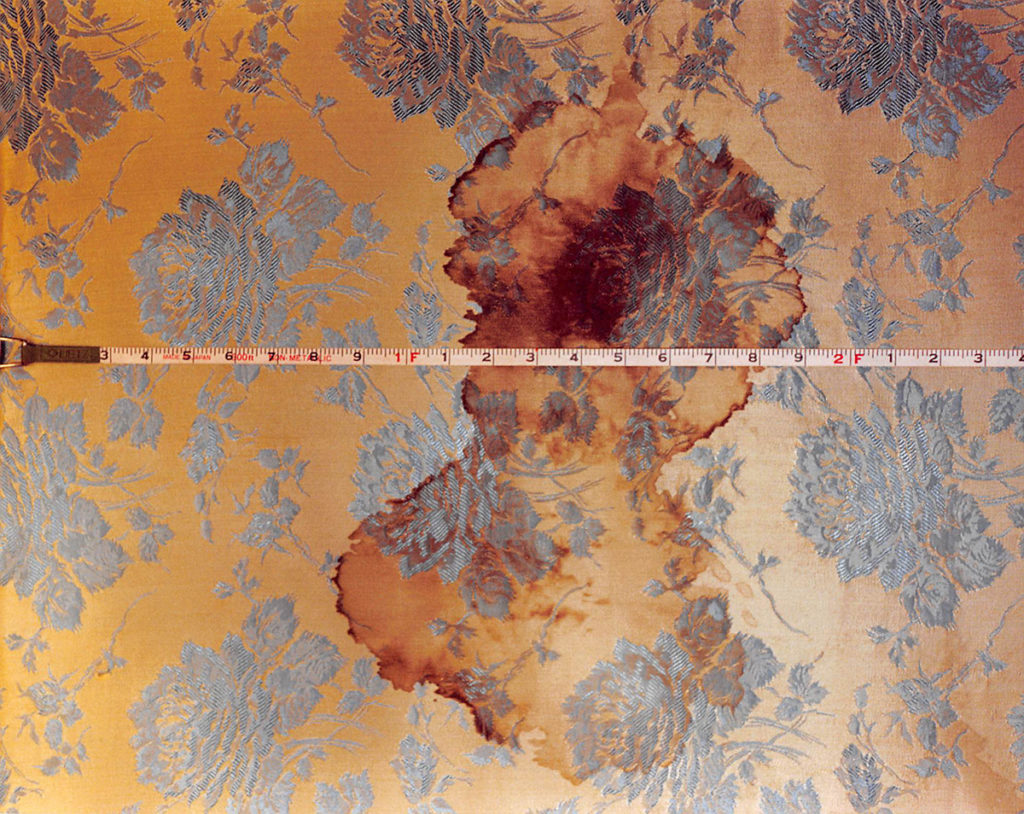

Dave Cawley: Rhonda said Doug had made Joyce strip the sheets after wrapping her hand. When he’d tried to mop up the blood on the mattress with the washcloth, he found it simply made the stain even larger. So, he’d flipped the blood-stained mattress and remade the bed with a fresh set of sheets.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): And she was, you know, begging him, y’know, ‘Let’s just call Birch and I’ll tell him whatever you want me to say, that you really didn’t rape me’ or whatever. But Doug was afraid that she would call Birch and then say that he was trying to rape me again. So Doug was just telling her, ‘It’s okay, I’m just gonna take you to some people and hide you out for awhile,’ ‘cause there was a court date coming up and he didn’t want her to be there, I guess.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda said Doug had made Joyce pack some clothes and makeup into a suitcase as if she were just going on a trip.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Doug kept telling her that, you know, ‘I’m not gonna hurt you, I’m just gonna take you to these people.’ So then, umm, I guess after he got her hand wrapped, umm, he got in her car and he said he made her drive up the canyon and they went up by Causey and he said, umm, he didn’t go far off the road. He just stopped the car and got out of the car and walked up this hill and it wasn’t very far off the road. And, umm, grabbed her neck and was choking her and then I think he stepped on her neck and stomped on it and smashed it.

Dave Cawley: By Rhonda’s account, Doug had killed Joyce with his own bare hands.

Terry Carpenter: How much of that’s true? I don’t know.

Dave Cawley: Terry told me he believed Rhonda was being honest with him.

Terry Carpenter: Rhonda’s a, a meek, mellow person and there’s no way that she was making any of that up.

Dave Cawley: But he doubted Doug had been completely honest with her.

Terry Carpenter: We know that’s not how he killed her because of all the blood that was between the mattress. He killed her in the apartment. He didn’t take her up on the mountain to kill her.

Dave Cawley: But which mountain? Where was Joyce? Rhonda didn’t seem to know, aside from it being somewhere near Causey Reservoir.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): And said he, umm, buried her as best he could and he didn’t have any, anything to really bury her, y’know, like a shovel to dig a hole that I recall. And he said he didn’t bury her very deep. He just, you know, like put leaves or shrubbery or dirt over her. And she had her purse at the time, he said, and he dumped all of her stuff out by her, her purse and then just left it. And he was saying, ‘You know, that was a mistake.’ He shouldn’t have left her purse and her ID, everything that was in her purse was right there by her body.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda said Doug acknowledged he would have to go back and fix that mistake.

Terry Carpenter: And then he went back a week or so later because it was bowhunting season and was afraid somebody’d find her laying on the ground and that’s when he buried her.

Dave Cawley: But let’s not get too far ahead. As the eastern sky started to take on the soft hue of impending sunrise on the morning after the murder, Rhonda had chauffeured Doug to a vacant lot at the intersection of Highway 89 and Oak Hills Drive in the city of Layton.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): And then he got out and umm, there was a camp area and where there’s a fire he started the suitcase on fire. I don’t know if he did the suitcase. I can’t remember because the suitcase seemed like it would take forever to burn. I just remember the clothes, for sure. He burned the clothes.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda waited in her car as Doug tended the fire, the growing light of dawn gaining in intensity with each passing minute. Rhonda said she then drove him to a spot along the Weber River, where he tossed the suitcase into the water. Then, they went home. At some point that morning, Doug’d discovered his pants and shoes were stained with Joyce’s blood. So he and Rhonda had left the apartment and drove to a place where Riverdale Road crosses the Union Pacific Railroad’s Riverdale Yard. Doug ducked under the viaduct, where he found a large drum or barrel. He put his bloodstained Levis in it, then set fire to them and walked away.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): You indicated that Doug told you he was going up to get rid of Joyce. You knew that that’s why he was going up there. Had he ever talked about doing that before to anyone else?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Yes. He talked to his friend, Billy Jack.

Dave Cawley: Further evidence of Rhonda’s forthrightness.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Rhonda starts to talk about the fact that he’s paid people to do this. And so other names come out.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda told Terry how Billy Jack had sawed the barrel off of a stolen gun, chickened out and buried the weapon in a field near Joyce’s apartment. She told Terry about meeting with Tom Peters at his girlfriend’s place in Salt Lake City, how Doug had turned an entire workman’s comp check over to Tom in the hopes he would “take care” of Joyce. How Tom had taken the money but failed to do the job.

She described how Doug ended up trying to pawn Joyce’s wristwatch, the one he’d left with her body but later retrieved. No pawnshop would offer him more than 50 bucks, so he’d tossed it out the car window while driving down State Street in Salt Lake City one day. Terry asked Rhonda if she was concerned at all about what they’d discussed.

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): I’m worried about, if Doug finds out. I’m really scared.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): What would Doug do?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): He’ll have someone come after me.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): And what do you think they’d do?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Kill me.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): ‘Kay. You believe that, Rhonda?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recording): Mmmhmm. Yep.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda took a polygraph, which showed she was being truthful. And she continued to feed information to Terry. She told him Doug had not stopped calling her, in spite of their divorce. Terry asked if she would be willing to record those phone calls. Rhonda said yes.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Shirley Lovell — Doug’s mom — died as a result of a pulmonary embolism on Friday, May 17, 1991. She was 55 years old. The family planned funeral services for the following Tuesday, May 21st, in Oak City, Utah, the tiny rural community where both she and Doug’s father had been raised and where Doug had spent his own early years.

Doug made an immediate request to the prison staff. He wanted to attend the funeral. The Utah Department of Corrections at that time classified Doug as a “level three” inmate. The medium-security ranking meant he had to remain within the prison perimeter at all times. Only level fives could leave the grounds. Still, Doug believed he had a strong case for an exception. His file, also known as his jacket, didn’t include any write-ups for serious violations. He was neat and polite. He didn’t brawl, he’d never tried to escape and he worked hard at his job in the prison sign shop. He’d become a leadman, with his own office.

Carl Jacobsen, who’d been one of his Doug’s guards when he’d first arrived at SSD back in ’86, often introduced him to visitors there. Carl had developed something of a rapport with Doug over the years. He’d since promoted to the rank of lieutenant. Managing visitation inside and outside the prison fell within Carl’s new responsibilities. Carl might’ve been the closest thing to an ally Doug had among the prison staff. But when he received the request for an off-site visit, it gave him pause. Doug, Carl believed, presented a flight risk. If given the opportunity, he might use the funeral to stage an escape.

While prison managers debated the question of whether to approve the funeral trip, Doug received a visitor at the prison. On the morning of Monday, May 20th, his boss at the sign shop told him his attorney was waiting to speak with him. Doug was at that time working to appeal his sentence in court. A new lawyer, Robert Archuleta, had signed on to help him. But that’s not who was waiting for Doug when he made his way over to the prison offices. It was Terry Carpenter.

Terry Carpenter (from May 20, 1991 police recording): Doug was advised of his rights per Miranda at which time Doug was asked if he understood each of these right and he stated that he did.

Dave Cawley: Terry didn’t make a tape recording of the conversation itself, but he did record these notes afterward.

Terry Carpenter (from May 20, 1991 police recording): I asked him with these rights in mind would you be willing to talk with me and he stated no.

Dave Cawley: Terry told Doug that was fine, he should just sit and listen. He then explained new information had come to light about the death of Joyce Yost. He now knew enough to secure a capital homicide charge.

Terry Carpenter (from May 20, 1991 police recording): Doug refused to talk about it and I told him that I knew that he was involved in this and he stated, ‘No, you’re wrong I don’t have anything to do with it, there is absolutely nothing that I know about the disappearance of Joyce Yost.’

Dave Cawley: Terry said he knew Doug had arranged to have Joyce killed and that a “payment was made.”

Terry Carpenter (from May 20, 1991 police recording): Doug shook his head, again denied any knowledge of it and stated he would gladly go to trial.

Dave Cawley: Terry had one other tactic to try. He told Doug the Department of Corrections was not going to let him attend his mother’s funeral. But he could make it happen.

Terry Carpenter (from May 20, 1991 police recording): The time that I approached him, I approached him uh knowing that his mother had just passed away and hoping that there may be some feelings there of remorse or that he may be in a frame of mind more willing to talk to me regarding the death of Joyce Yost, knowing that she was also someone’s mother.

Dave Cawley: Terry said if Doug wanted to go, he had to first give up the location of Joyce’s body.

Terry Carpenter: He just flat adamantly denies anything. He doesn’t have anything to do with it. He has no knowledge of it and just flat tells me that I’m wrong.

Dave Cawley: Doug responded by saying, “[expletive] you.”

Terry Carpenter: You sit and look at him and know without a question that he’s lying to you and you can just flat see the devil in his eyes.

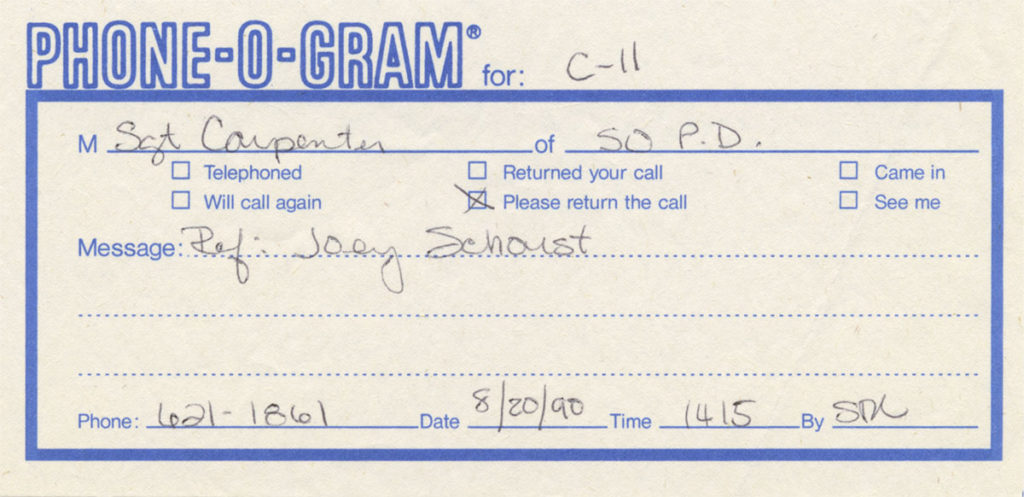

Dave Cawley: Doug told Terry he couldn’t keep him there then he stood and walked out of the room. Terry wasn’t done at the prison, though. He had the guards haul in another inmate: Tom Peters. He’d only just learned of Doug and Tom’s friendship from Rhonda.

Terry Carpenter (from May 1, 1991 police recording): How did he know Tom?

Rhonda Buttars (from May 1, 1991 police recordings): He knew Tom from last time when he was in prison.

Dave Cawley: Terry proceeded to tell Tom he was aware Doug had paid him to “take care” of Joyce Yost. Tom, in response, suggested a hypothetical. Suppose, he said, a friend came to another friend and offered to pay to have a woman taken care of. The second friend agrees to the point of taking the money, but with no intention of ever killing anyone.

Terry Carpenter (from May 20, 1991 police recording): And then Mr. Peters’ tense changes and he says, ‘I took the money. At the time I was h—, I mean,’ and he says it just that way. ‘I mean this person at that time was a heroin addict and he took the money for the purpose of getting high on heroin and that’s exactly what I did. My girlfriend and I—’ and then he realizes again that he has changed tenses. He stops and he says, ‘This person and his girlfriend then took the money and went out and got high on heroin with no intentions whatsoever of having anything to do with the murder.’

Dave Cawley: Terry asked Tom if he would tell that story from the witness stand.

Terry Carpenter (from May 20, 1991 police recording): And Tom thought for a minute and said, ‘No, I can’t deny it, it’s true but I will invoke my right.’ And I says, ‘you mean your Fifth Amendment right to remain silent to avoid incriminating yourself?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’

Dave Cawley: Tom said he had good reason to worry. Doug Lovell was not his friend.

Terry Carpenter (from May 20, 1991 police recording): Tom indicated to me that he was afraid of problems from Doug. He says, ‘If I can see him coming I’ll be ok, but Doug’s the type that he will come up and get you from behind.’

Dave Cawley: Shirley Lovell’s funeral came and went. Doug did not attend.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: The swelter of the southern Nevada afternoon had started to recede from the Moapa Valley. Heat radiated from the scorched ground, even as twinkling stars emerged in the violet blanket of the clear desert sky. Ron and Deb Barney were at home in Logandale, a small community between I-15 and Lake Mead, about 50 miles northeast of Las Vegas. Just after 9 p.m. on May 23, 1991, they heard a knock at the door. When they answered, they found two men standing on the doorstep: sergeant Terry Carpenter and lieutenant Val Shupe of the South Ogden, Utah police department. The Barneys invited the officers inside to talk. Terry had learned Ron was one of Doug’s closest friends. He told Ron he’d soon be arresting Doug for the murder of Joyce Yost.

Terry Carpenter (from May 23, 1991 police recording): Mr. Barney indicated to me that he didn’t believe in any way, shape or form Doug Lovell was involved, that he was a good person.

Dave Cawley: Terry did not record the conversation, again, only these notes after-the-fact.

Terry Carpenter (from May 23, 1991 police recording): We talked in some detail about the fact that this good person had committed a series of armed robberies, that this good person had committed a very brutal rape upon a woman, that this good person had been poaching.

Dave Cawley: Deb scooted their kids to bed as it became clear the conversation was turning to more sensitive matters.

Terry Carpenter (from May 23, 1991 police recording): He had some question about whether he raped the woman or not. Doug had told them that they actually had just had sex together and the woman wanted the relationship to go further and Doug said no and she got mad and screamed rape.

Dave Cawley: Terry countered this, explaining in some detail how the evidence showed Doug’s assault on Joyce had not been consensual.

Terry Carpenter (from May 23, 1991 police recording): And I made the comment that, ‘Yeah, whenever Doug is on dope, that that’s what happens to him.’ And uh, Debbie immediately made the statement that, ‘Doug doesn’t do drugs.’

Dave Cawley: Terry said yes, Doug did do drugs, the prescription kind. There was the matter of Doug’s phony back injury during the summer of ’85, for which he’d obtained several prescriptions.

Terry Carpenter (from May 23, 1991 police recording): Also indicated that the night that Joyce disappeared that Doug was taking a very strong drug at that time allegedly for his back which there is much in question as to whether the back problem is a legitimate deal or just a guise for him to receive some kind of drugs while he is in prison.

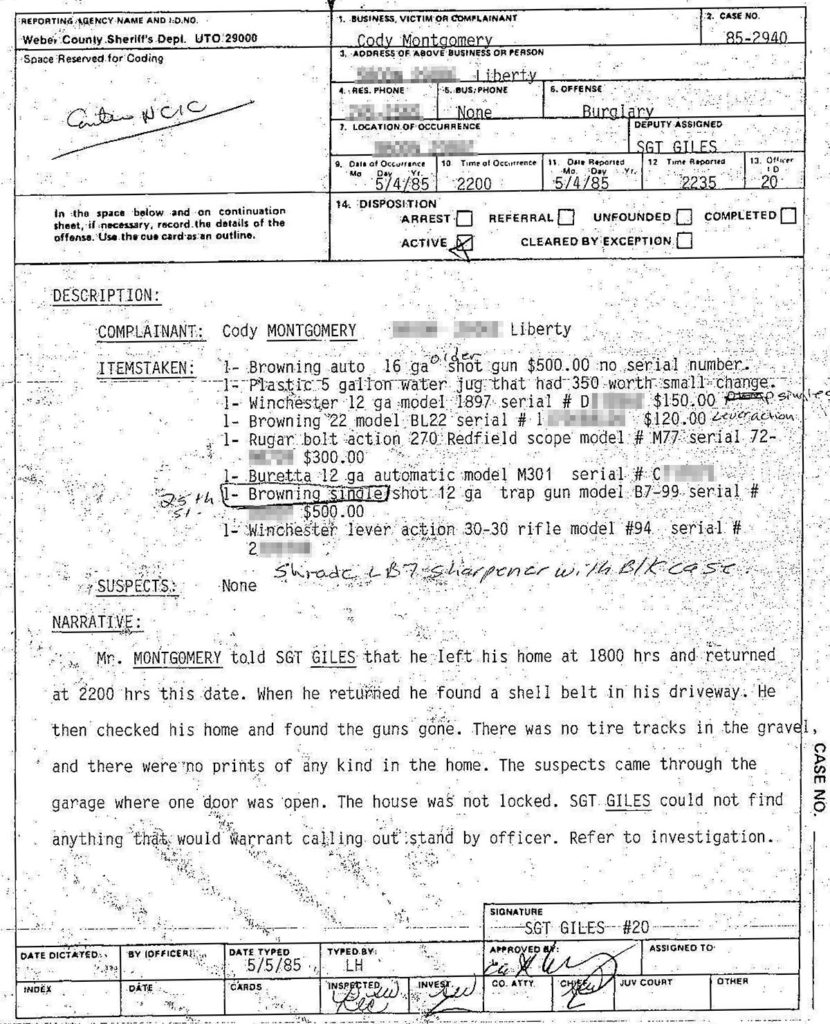

Dave Cawley: And how about the issue of the stolen guns, the ones Doug and Billy Jack had taken from the home of Cody Montgomery in May of ’85? The ones they’d buried behind the cabin near Callao.

Terry Carpenter (from May 23, 1991 police recording): I asked Mr. Barney if he had any knowledge about Doug burying some guns. Ron paused for probably 10 seconds and stared at the table and then says, ‘Well yeah, he did tell me about some stolen guns, he buried them someplace. I’m not sure where he buried them.’

Dave Cawley: Terry already knew where the guns had come from and where at least some had ended up.

Terry Carpenter: And Ron was very hesitant to talk about them.

Dave Cawley: Doug had told the Barneys he expected a judge would soon overturn his sentence. They’d discussed having him come stay at their place in Nevada once he won his freedom. Terry asked if that’s really what they wanted, considering how Doug had been convicted of armed robbery, how he’d kidnapped and sexually assaulted a woman, how he’d stolen guns and cars, how he’d poached deer.

Terry Carpenter (from May 23, 1991 police recording): With that understanding they began to think and Debbie made the comment that she was concerned about her children, that they had become fairly good friends with Doug and that they had some major concerns about Doug coming to live with them.

[Scene transition]

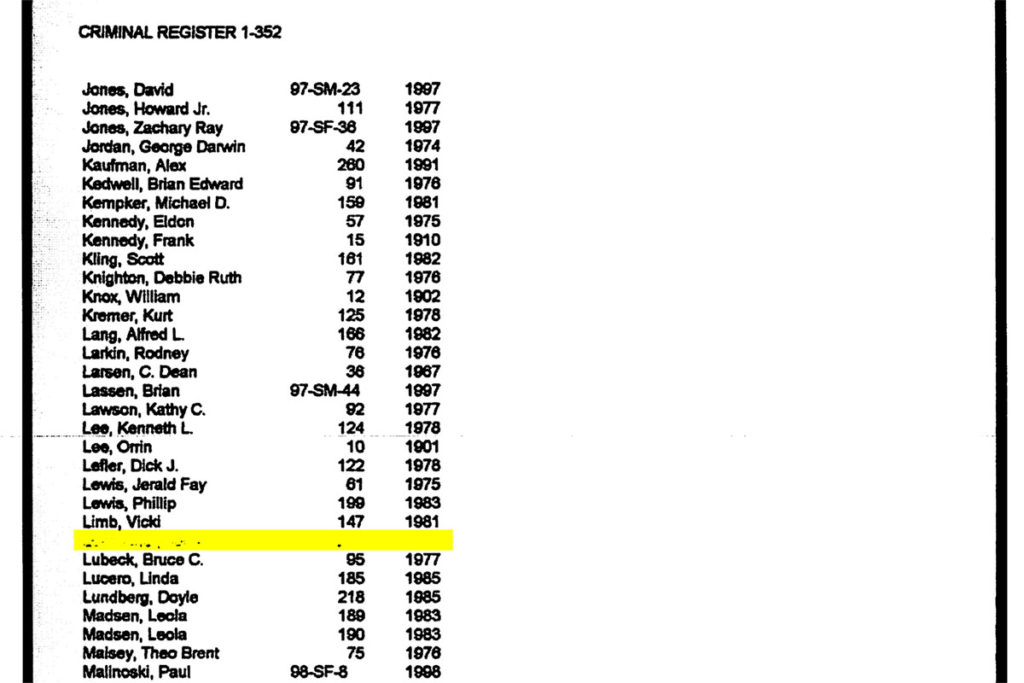

Dave Cawley: In the week following his mother’s funeral, Doug Lovell came across a newspaper story that caught his attention. It dealt with another inmate at the Utah State Prison, a man named James Carlos Foote. Foote had been charged with sexually abusing a child in ’84, when he’d touched a six-year-old girl while lifting her into his truck. Foote, who had no prior criminal history, cut a plea deal and received a sentence of one-to-15 years in prison.

Parole board guidelines suggested the punishment for Foote’s crime should’ve been two years of incarceration. He’d gone before the board three times since arriving at the prison, and was each time peppered with questions about other cases of child sex abuse in which he might have been involved. Foote denied having any sexual contact with any other children. As a result, the board determined he was not being forthcoming and declined to grant him a release date.

Foote filed suit against the board, claiming his estranged wife — who worked for the Utah Department of Corrections — had added unfounded accusations about him abusing other neighborhood children to his file. He said the board was essentially punishing him for crimes he’d not been convicted of, depriving him of his constitutional right to due process. His lawsuit had made its way to the Utah Supreme Court in November of 1990. In its ruling in March of ’91, the high court justices unanimously agreed due process rules did apply to the board of pardons, same as to the courts.

In other words, Foote had a right to know what was in the file and to challenge it. So, in May of ’91, after serving more than six years, Foote filed a second lawsuit. That’s what’d landed his story in the paper and before the curious eyes of Doug Lovell. Doug saw parallels to his own situation. He believed Judge Rodney Page had sentenced him for murdering Joyce, not for kidnapping and sexually assaulting her. And Doug had not been able to review the pre-sentence report Page relied on when making his decision.

Doug had a friendly prison guard make a copy of the newspaper story. He placed it in an envelope and addressed it to Rhonda. Then, he called her… and Rhonda rolled tape, starting this recording.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Hello?

Operator (from recorded 1991 phone call): Hi, will you pay for a collect call from Doug?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Uh huh.

Operator (from recorded 1991 phone call): Thanks, go ahead.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Hi.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Hi.

Dave Cawley: …not to discuss his own mother’s funeral, which Rhonda had attended without him days earlier, but to share the good news.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Because see now when I go to the board, they can’t even ask, they can’t even, they can’t even make a mere statement, y’know, ‘What do you know about Joyce?’ They can’t even ask that anymore because of what’s been ruled.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): And a lot of things are swinging now in my favor. And I think they’ve always been hoping that umm, y’know, that when I eventually went to the board, if I lost my appeal, if I went to the board, the board could say, ‘Hey, y’know, what about this?’ Y’know, and then keep me here for X amount of years longer. And now that can’t happen.

Dave Cawley: Doug had more good news for Rhonda. He told her about his new attorney, Robert Archuleta. Robert was already trying to track down a copy of Doug’s pre-sentence report, so they could go about challenging what was in it. That wasn’t the only update he had to share.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): I guess Carpenter’s been assigned to the case.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Who?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Carpenter. Terry Carpenter.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda did not let on she was by then well acquainted with Terry Carpenter. Doug didn’t bother to ask, continuing right on describing their meeting the day before the funeral.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): I said uh, ‘I got nothing,’ y’know, ‘I got no statement.’ Y’know, I told him, ‘If you want to turn the recorder on, I’ll tell you that, y’know what I’m gonna tell you right now. I don’t know anything about it. I wasn’t involved, directly or indirectly, in it.’ And I says, ‘And I don’t know and I don’t think anybody else even knows that this woman is deceased.’ I says, ‘Now, if you want me to make that kind of a statement, I will.’ And he says, ‘Well, that’s not what I’m looking for.’ I says, ‘Well then what you want is for me to say something that’s not true. Y’know, what you want me to do is say that I was involved in something that I wasn’t. And I can’t do that.’

Dave Cawley: Rhonda mentioned a detective had dropped by her apartment on the day of the funeral, but she wasn’t at home.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): So they’re probably trying to look for me, too.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah, well and I’m, I’m surprised they haven’t got ahold of you by now. I figured you would have been the first one that they got ahold of.

Dave Cawley: At no point during any of this did Doug take a moment to express grief or sadness over the loss of his mother. The following week, after Memorial Day, he called Rhonda again. This time, he did want to talk about his mom, or at least her life insurance. Doug said it appeared he and his brother Russ were poised to split about $81,000. The money would mean he was all set for when he got out. Rhonda told Doug Carpenter had showed up at her apartment with a search warrant.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Well, I got a visit last night.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Did you?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yep. They came and, they came and, uh, searched the house and went through everything.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Did you let them?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah, they had a warrant.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Did they really?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yep.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): What’d they find, what did they take?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Uh, some pictures.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): What kind of pictures?

Dave Cawley: Hunting pictures. Polaroids of Doug, Rhonda and Billy Jack at the cabin near Callao.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): I don’t know how many they took but they took some. I’m not sure which ones. I think, well, I think of, like, well, everybody. Y’know, your friends. They wanted to know their names and stuff.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): No kidding?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yep.

Dave Cawley: Doug didn’t seem to like this one bit.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Huh. Did they try to question you?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): No, not really. They just said they’d get back with me. They just wanted to do a search. That was basically what they were doing.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Huh.

Dave Cawley: The topic of the pictures would come up again and again in the days that followed. At one point, Rhonda told Doug his life would be easier if he just told the truth. He brushed off that suggestion, saying he wanted the photos back as soon as possible.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Well, I don’t think they’ll keep them. Why you worried?

Dave Cawley: He didn’t answer the question. But he did urge Rhonda to come visit him that weekend. All of this action in the case had him wanting to talk to her, face to face. Not over the phone, where they might be monitored. So, it came as a disappointment when he called Rhonda on Sunday, June 2nd. The weather was bad in Utah and Rhonda told Doug she wasn’t going to drive down to the prison for a visit. Maybe next week. Doug couldn’t wait. He took a risk and brought up, in a round-about way, the topic of Joyce.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): But umm, y’know you shocked me by something you said the other day.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): What?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): About the truth?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Why?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): I, I just couldn’t believe you said that. It still blows me away, totally away.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Why, what do you mean?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): That you would ask me to do something like that.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Well, why?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Do you know what you’re asking?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Huh uh. I guess not.

Dave Cawley: There was a lot of static on this part of the call and it’s difficult to understand, even after aggressive noise reduction. What Doug said there was shocked by Rhonda’s suggestion that he tell truth. He asked if she knew what she was asking. Rhonda said “I guess not.”

In this next clip, Rhonda tried a different approach, telling Doug she wondered how he lived with it. You’ll hear Doug say “in all honesty Rhonda, what I’ve been living with for years is far worse than that.”

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): I don’t know, I just wonder how you live with it.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Well, in all honesty Rhonda, you know, what I’ve been living with for years is, is far worse than that.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): What does that mean?

Dave Cawley: What could Doug have possibly been referring to? Doug said he didn’t want to talk about it. It was a subject he only addressed with Kate Della-Piana, his prison therapist. Listen again and you’ll hear Doug say “on a scale of 1 to 10, this doesn’t even rate and I’ve lived with it for a long time.”

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): But I can assure you that, that this, doesn’t even, y’know on a scale of 1 to 10, doesn’t even, doesn’t even uh, doesn’t even rate. Y’know, and I’ve lived with it for a long time.

Dave Cawley: What ever this other mystery problem was, he didn’t provide specifics. He only would say it caused him a great deal of shame and guilt. At this, Rhonda again said it was perhaps time to spill his guts, to get it all out. Doug said “Get what out? I didn’t do anything.” This triggered an argument, with Doug telling Rhonda he worried about her and what she might do.

Doug Lovelll (from recorded 1991 phone call): I mean uh, you’ve never been through this, Rhonda.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Well, excuse me. So should I do it just to experience it or what?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): No, no. Hey and umm, don’t try to fight with me—

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): I’m not, man. Don’t try and fight with me.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): I’m not.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah, you are.

Dave Cawley: In frustration, Doug told Rhonda he didn’t know her anymore. She agreed, saying they just weren’t on the same wavelength. Time apart, she said, does that to people.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: Doug Lovell’s new attorney called Rhonda Buttars late in the day on Friday, June 14th, 1991.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Hello?

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): Is this Rhonda?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yes.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): Oh Rhoda, this is attorney Robert Archuleta.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Uh huh.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): How are you?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): I’m good, how are you?

Dave Cawley: Robert apologized for not having his notes in front of him, a fact made clear when he referred to Joyce Yost as Janet Riost. He explained he’d talked to Terry Carpenter about his recent visit to Doug at the prison.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): I did get some information out of this detective Carpenter. He said he’d talked with four people who’d had discussions with uh, with uh, with uh, Mr. Lovell about, I suppose, having her executed or murdered.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Hmm.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): And, y’know, this guy, I think he’s lying to me about that.

Dave Cawley: That’s because Robert said Doug had consistently denied any involvement with Joyce’s disappearance.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): Doug seems like a pretty nice guy to me.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah, he is. He’s a good guy. Nice guy.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah, that’s what I think, too. I mean, I don’t know anything about your relationship but otherwise he seems like a pretty good guy and he insists he didn’t do this. He says, ‘No, I didn’t kill anyone.’

Dave Cawley: Robert asked Rhonda if she’d ever been questioned by the police.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Ever? Yeah. Birch, umm, did years and years ago.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): And what’d you tell him, you didn’t know anything?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): And that’s pretty much true, isn’t it?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Uh huh.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): I mean, you didn’t know any more than you’ve told me.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Right.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda didn’t tell Robert about her more recent conversations with Terry Carpenter. She only mentioned Terry had showed up at her apartment with a search warrant. She explained how Terry had seized photos of Doug and his friends.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): And who were your friends?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Umm, they took some of Tom Peters, Billy Jack, Deb and Ron—

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): Tom Peters, that’s it. That’s the one that they alleged. Uh, Billy Jack did you say?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Uh huh.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): Who else?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Deb and Ron Barney.

Dave Cawley: Robert told Rhonda if Terry came back around asking any more questions, she should refuse to answer. He said the police were simply shaking the tree to see what might fall out.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): See they made some pretty outlandish things about them. They told me they think Doug has killed two people.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Oh really?

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): Uh huh. Then somehow they, they’ve alleged in somewhere that he was part of this automobile theft ring.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Hmm.

Dave Cawley: Rhonda played ignorant, saying Doug hadn’t really been in trouble with the law that much prior to the rape case.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): ‘Kay. Otherwise, did you have a pretty good marriage?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah.

Robert Archuleta (from recorded 1991 phone call): It was alright?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): It was alright, yeah.

Dave Cawley: Later that same night, Doug called Rhonda. She told him about her conversation with Robert.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): I feel like I was on trial. God, 20 questions, man.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): From him?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): The attorney?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah, he’s, he’s, he’s good, Rhonda.

Dave Cawley: Doug said Robert wanted to represent him, if South Ogden police made good on the threat of filing a capital homicide charge. He’d given Robert marching orders, if that were to happen.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): ‘I want you to represent my ex-wife.’ I says, ‘I’m not worried about myself.’ I says, ‘I want her taken care of. I don’t want her to spend a night in jail. If, if bail, uh, if she’s arrested, I want bail, I’m going to get with Russ and dad, I want bail immediately arranged.’ And uh, and I told him, I says, ‘Don’t worry about defending me.’ I says, ‘I want her defended.’ And he says, ‘Well, y’know—’

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): So what’re you trying to say, that’s where I’m going?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): No, no, no.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): [Expletive]

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): No, Rhonda, I’m not. I am—

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): I can’t deal with this [expletive], Lovell. I told you before. I can’t deal with it again. The nightmare, the hash over all this [expletive]. If they come and do that, I swear to God, I’m gonna freak out.

Dave Cawley: Doug promised Rhonda if she were arrested, she would be out of jail within hours.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): I don’t care. It’s, it better not happen. I’ll be so friggin’ mad, you won’t even, oh God. See sparks coming out of my face. ‘Cause he’s scaring me. My voice started shaking, man. He says, ‘Hey, y’know, they sound like, y’know, they got something.’ And they told, that cop told him, ‘Hey, I’m arresting his ex-wife and three other friends.’ And I just went, ‘Oh that’s, that’s good to know.’

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Well—

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): And goes, ‘Well, what’d they say to you?’ And I go, ‘Nothing.’

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Rhonda, you had nothing to do with it. I had nothing to do with it. None of my friends had anything to do with it. You have nothing to worry about. All they’re trying to do is shake something. They’re trying to shake a tree and seein’ if an apple falls.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Oh God, you sound like him.

Dave Cawley: Doug couldn’t reassure his ex-wife, try as he might.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): And I’m making all the arrangements for, for him to be there for you and for, y’know, to be bailed out.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Oh, well that’s comforting, Doug.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Well, Rhonda, it may happen. It may happen.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): I know, and that’s real comforting to know. I want to go there again, [expletive].

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Rhonda, I, y’know I was hoping you’d be, at least be comforted to know that I’m trying to do everything I can for you.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): No you’re not.

Dave Cawley: Doug told Rhonda they could talk about it more in person on Sunday, when she came to visit him. Their conversation was cut off anyhow. But he dialed Rhonda again first thing the next morning.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): What’re you wearing?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Huh?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): What’re you wearing?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): When?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Now.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): My jammas.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Really?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Mmmhmm.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Hmm.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Why?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): I just always like knowing what you’re wearing when I talk to you. I like to picture you.

Dave Cawley: This time around, he didn’t mention the attorney, his appeal, or Joyce Yost. He simply reminded Rhonda of her plan to come down and visit that weekend. And, he told her to tune into his favorite TV show later that night to see country music videos. Doug’s favorites were Lorrie Morgan and Patty Loveless. But he’d also just heard the Alabama song “Here We Are” from their 1990 album “Pass It on Down.”

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): I listened to the words to it really close yesterday and it’s you and I to a T except for one line.

Dave Cawley: The chorus of that song goes: “We had to break it all down to build it back up, lean on each other when the times got rough, how we survive going through so much, baby you and I could write a book about love.” As for that one line that Doug said didn’t fit? “We’re still together after all this time.”

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Rhonda followed through on her promise to visit Doug that Sunday, June 16, 1991. Doug was almost up to 200 pounds, the extra weight in the form of muscle. Rhonda complimented him saying, “You look good.” He said, so do you. Then, he asked if she’d watched the country music videos. Rhonda said she had. He said Patty Loveless was beautiful and Rhonda resembled her.

Terry Carpenter: It’s kind of interesting ‘cause Rhonda’s pretty nervous.

Dave Cawley: Doug didn’t know it, but Terry Carpenter was also hearing his sweet talk. Rhonda had agreed to wear a recording device into the prison.

Terry Carpenter: I have one that we have hidden up in a bra strap on Rhonda.

Dave Cawley: It transmitted in real-time to a receiver, which Terry had with him in an observation room just above the prison’s outdoor visiting area.

Terry Carpenter: The location that I’m in, I’m able to be up above them and looking down into the room that they’re in.

Dave Cawley: Terry had also wired Rhonda with a backup, standalone recorder that was strapped to one of her thighs.

Terry Carpenter: There’s a couple of times that Doug would try to put his arm around her and she’d slap his arm away and he’d try to reach over and put his arm on her leg and she’d slap it away and wouldn’t. He’d look at her like ‘What’s the matter with you?’

Dave Cawley: Rhonda went on chatting. This was mostly performative, a show of normalcy, of boring routine for the other people scattered around in the visiting area. Doug dropped the pretense, once it seemed no one was paying them any attention. He leaned in and asked Rhonda, if he were charged with Joyce’s murder, would she testify?

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): In all honesty Rhonda, you know, it, I mean, it crossed my mind, but I didn’t believe it, you know? I mean, I just couldn’t picture you sitting on the stand testifying against me. Uh, and I couldn’t see Tom doing it either.

Dave Cawley: I know that’s pretty garbled, but Doug said “I just couldn’t picture you sitting on the stand testifying against me. And I couldn’t see Tom doing it either.” Much of this audio from this wire recording will be difficult to understand. I’ll interpret as necessary.

Doug reassured Rhonda he had never and would never tell anybody the truth of what he’d done to Joyce. In fact, he said he’d lied to his therapist, Kate Della-Piana, to throw her off the scent. And he said if the police tried to arrest Rhonda, he’d take care of it, just as he had with the poaching charge. Rhonda said she didn’t want to go through it, to have everyone at work talking about her.

Rhonda Buttars (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): I don’t want to go through it. Do you hear me? I don’t want to go, I don’t want them coming to work again, or even if it’s home. Everybody’s going to find out again and I’m going to be the talk at work. I can’t deal with this, Lovell.

Dave Cawley: An exasperated Doug asked Rhonda just what she wanted him to do about it. How could he reassure her? Her answer was simple: tell the truth. Doug said that was not an option. If he came clean and admitted what he’d done to Joyce — both the rape and the murder — it would mean his life.

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): I committed a first-degree felony to cover another felony. It’s the death penalty. At the very least, they’re going to give me life without parole. If I cooperate with them, and go to them, they’re going to give me life without parole.

Dave Cawley: “I committed a first-degree felony to cover another felony. It’s the death penalty.” Rhonda said she didn’t understand. After all, murderers cut deals all the time. He’d probably just do an extra five years or something. No, Doug said. There’s a big difference between something like manslaughter, say when two guys are in a brawl and it goes too far, and what he’d done to Joyce.

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): I premeditated, premeditated. I planned to kill Joyce. I planned to end Joyce’s life. That’s premeditated capital homicide.

Dave Cawley: “I planned to kill Joyce, I planned to end Joyce’s life. That’s premeditated capital homicide.” Doug had just confessed to murdering Joyce Yost on tape. Rhonda asked if Doug believed in an afterlife. He said he did.

Terry Carpenter: And Rhonda says to him ‘Doug, you realize that your mom now knows that you killed Joyce.’ And his comment is ‘my mom knows now a lot worse about me than just Joyce.’

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): Mom knows. Mom now knows far worse about me things than that, Rhonda. And I, and I, I know I at least have the satisfaction of knowing that when mom passed on, that I was correcting my life. I was doing everything I could, Rhonda, to correct my life, you know? And mom knew that I was pretty happy, you know? And I believe that she believed that.

Dave Cawley: “Mom now knows far worse about me things than that.” For the second time in just a matter of weeks, Doug seemed to imply his raping and murdering Joyce was not the worst thing he’d ever done.

Terry Carpenter: You tell me what can be worse than killing somebody, if he hasn’t killed multiple people.

Dave Cawley: What about Joyce’s body? Rhonda asked if someone might have found it. No chance, Doug said. He alone knew where it was. He said he hoped to someday share that location with his therapist, Kate, so Joyce’s family could have closure. But only if he could do it on his terms, in a way where he’d be protected. Otherwise, it would be the death penalty. Which brought Doug back around to the question of who could possibly testify against him. So, what about it, Rhonda?

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): I want to. I want to know straight up. If, you know, [unintelligible] hits the fan, I mean, and it could get heavy, Rhonda, are you gonna ever testify against me?

Dave Cawley: “Are you gonna ever testify against me?” Rhonda said no, unless she had to. If she ended up in jail, he had better start talking. At this, Doug laughed. Police were fools, he said. He’d embarrassed them after the poaching arrest and he would do it again. But this was good. He felt reassured. He’d looked Rhonda in the eyes and heard her say she was not going to talk.

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): But I, I just wanted to hear from you, y’know? Look at you, to hear it, you won’t testify.

Dave Cawley: Soon, he promised, everything would be back to the way it was before. He wanted to be out with her. He was sorry for their hard times, but he was correcting himself and would be back to the nymphomaniac he was at 17 years old.

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): I want to be out there with you, Rhonda.

Rhonda Buttars (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): I want you out there too, D.L.

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): I mean, I want us out there. I want to be husband and wife again. And ah, I’ll be honest with you. It would break my heart if you ever got married again, because I know that no two people were more right for each other than you and I. And I know I’ve had some hard times out there and I know that I took some bad things out on you. And I’m sorry. All I can tell you is that I’m correcting all that now, and ah, will be back to myself where I was when I was 16, 17 years old. Yeah, I was a nymphomaniac back then.

Rhonda Buttars (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): I remember Lovell.

Dave Cawley: Doug vowed to shower her with sweet, sweet romance. He told his ex-wife, the woman who alone could undo him with her testimony, she was his future. Rhonda responded by saying “then tell.” Doug said if he told the truth, they wouldn’t have a future together. Telling the truth was his “final straw.”

Rhonda Buttars (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): Then tell.

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): Tell the truth? Rhonda, then we would never have a future.

Rhonda Buttars (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): Yes we would. Aren’t you willing to find out what would happen if you say, what if by chance something comes out? I mean, make it vague, you know, ‘What if, what if I did do it? What would happen?’

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): Okay. That’s, that’s a final straw. That isn’t something I have to deal with now.

Dave Cawley: If it came down to that, if Doug were cornered and forced to admit he’d killed Joyce, he promised Rhonda he would not reveal her role.

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): Now, if I came forward and tell the truth, then I’m gonna be on the news. I don’t want that. If I ever did tell the truth, Rhonda, I would never say that you knew anything about it. Ever. Okay?

Dave Cawley: What’s more, when he got out, Doug said he would be a reformed man. No more sleeping around, no more girlfriends, only Rhonda.

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): Y’know, I feel more loving and I feel more romantic.

Rhonda Buttars (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): I’ll believe it when I see it.

Doug Lovell (from June 16, 1991 wire recording): Well I, well I’m coming to you, Rhonda. Like I said, like a freight train.

Dave Cawley: “I’m coming to you … like a freight train.” When they stood to leave, Doug planted Rhonda with a kiss.

[Scene transition]

Dave Cawley: Later that night, after Rhonda had returned home from the prison, she received a phone call.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): I want to treat you like a lady and make you feel like a woman, 24 hours day and night.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Hmm, scary.

Dave Cawley: It was Doug.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Well listen, thanks for coming down today. I, uh, did it help you any?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): It helped me tremendous, ‘cause there’s a couple things I needed to hear from you and uh, and I, I believe it. And it helped me a lot. And uh, I meant everything I said to you, Rhonda.

Dave Cawley: That included, Doug said, a promise to be together with Rhonda, Alisha and Cody as complete family.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Get ready for a train, okay?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Hah. Yeah, your kiss blew me away.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): You’re gonna have a loose one on your hands.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Huh?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): ‘Cause you’re gonna have a loose one on your hands.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Your kiss blew me away.

Dave Cawley: The kiss.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): And the kiss was nice. And uh, I got goosebumps.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): (Laughs)

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): I did, I honestly did.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah, it made me sweat.

Dave Cawley: The following weekend, on Saturday, June 22nd, he phoned Rhonda again.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): When you gonna come down and see me again?

Cody (from recorded 1991 phone call): Umm, maybe tomorrow.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Maybe tomorrow?

Cody (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Alright, that’d be neat, huh?

Cody (from recorded 1991 phone call): Uh huh.

Dave Cawley: The recordings Rhonda made of these phone calls captured many conversations like this between Doug and the kids. I’ve chosen not to share almost any of that, out of consideration for their young ages and personal privacy. The clips I’m using here are only included because they provide important context regarding Doug, his methods of persuading Rhonda to visit him and his knowledge of the backcountry. To that last point: Doug asked Alisha if she’d enjoyed her time with her biological father the prior weekend. She said, “Not really.”

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Did you go up Ogden Canyon to camp?

Alisha (from recorded 1991 phone call): Huh uh, we went, I don’t know. But we went up there and umm, couldn’t find a place to camp so we just went back to his house.

Dave Cawley: Doug presumed it must have been too crowded for Alisha’s father. Doug said it would’ve gone differently had he been there. He knew how to get off the beaten path, away from other people.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Can you remember ever camping with me when you was little?

Alisha (from recorded 1991 phone call): No.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Can’t you really, honey?

Alisha (from recorded 1991 phone call): Mmmnmm.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): That’s too bad. Gosh, we use to, me and you and mom used to go up to some doozy places, honey. We used to four-wheel drive all the way up the mountain.

Alisha (from recorded 1991 phone call): I remember some of them. Like going up there and getting stuck.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): (Laughs) Yeah, we did that too. Do you remember spending the night in the creek?

Alisha (from recorded 1991 phone call): Nuh uh.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Remember, the truck got stuck in the middle of the creek, this, this little river and we had to spend the night in the truck and we was right in the middle of the creek?

Alisha (from recorded 1991 phone call): Mmmhmm and we had to sleep on the, in the truck. Mmmhmm.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): That was, that was a time I’ll never forget, honey. Believe it or not, I had a lot of fun. That was uh, that’s camping to me. I hate being around other people when I leave the, when I get up in the mountains I don’t like being around other people. That’s not, that’s not like camping.

Dave Cawley: Doug told Alisha he would try to arrange for her to go visit his dad’s cabin, just as soon as the rest of the family could get together. When Rhonda came back on the phone, Doug asked if she’d read the articles he’d sent to her.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yep.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): What’d you think?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Sounds good.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): It does, huh?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yep.

Dave Cawley: As I explained earlier, they dealt with a Utah Supreme Court decision and a lawsuit filed by a state prison inmate. Taken together, Doug believed they meant the state’s board of pardons would not be able to ask him about or even consider Joyce’s disappearance when he came up for a parole hearing.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): They don’t have, they don’t have the power anymore. The Supreme Court took it away from them. It’s like they held it, it’s like, ‘Na na na.’ And they went, ‘Whoa!’

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah. They had too much, I think.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah, they got way too much. Man, what they been doing with people here is [expletive].

Dave Cawley: Getting the articles to Rhonda, and getting her to read them, had taken no small effort on Doug’s part. Now, he wanted the newspaper clippings back for his own files.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Can you send me those articles back though?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Yeah.

Dave Cawley: And in parting, he reminded Rhonda of his favorite Saturday night event.

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): Hey, you know what comes on at 10?

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): Oh God, what?

Doug Lovell (from recorded 1991 phone call): My country videos, Rhonda.

Rhonda Buttars (from recorded 1991 phone call): I know, what? Who?

Dave Cawley: Doug said Restless Heart would be on, but they probably wouldn’t play his favorite song. Roseanne Cash would sing her latest. Her hit single at the time was a song titled “What We Really Want.” Rhonda would like it, Doug said. The opening verse went like this:

“We tried to make ourselves pay for something we’ve never done. We threw the best parts of life away on street talk, strangers and drugs. What we really want is love what we really need is love.”