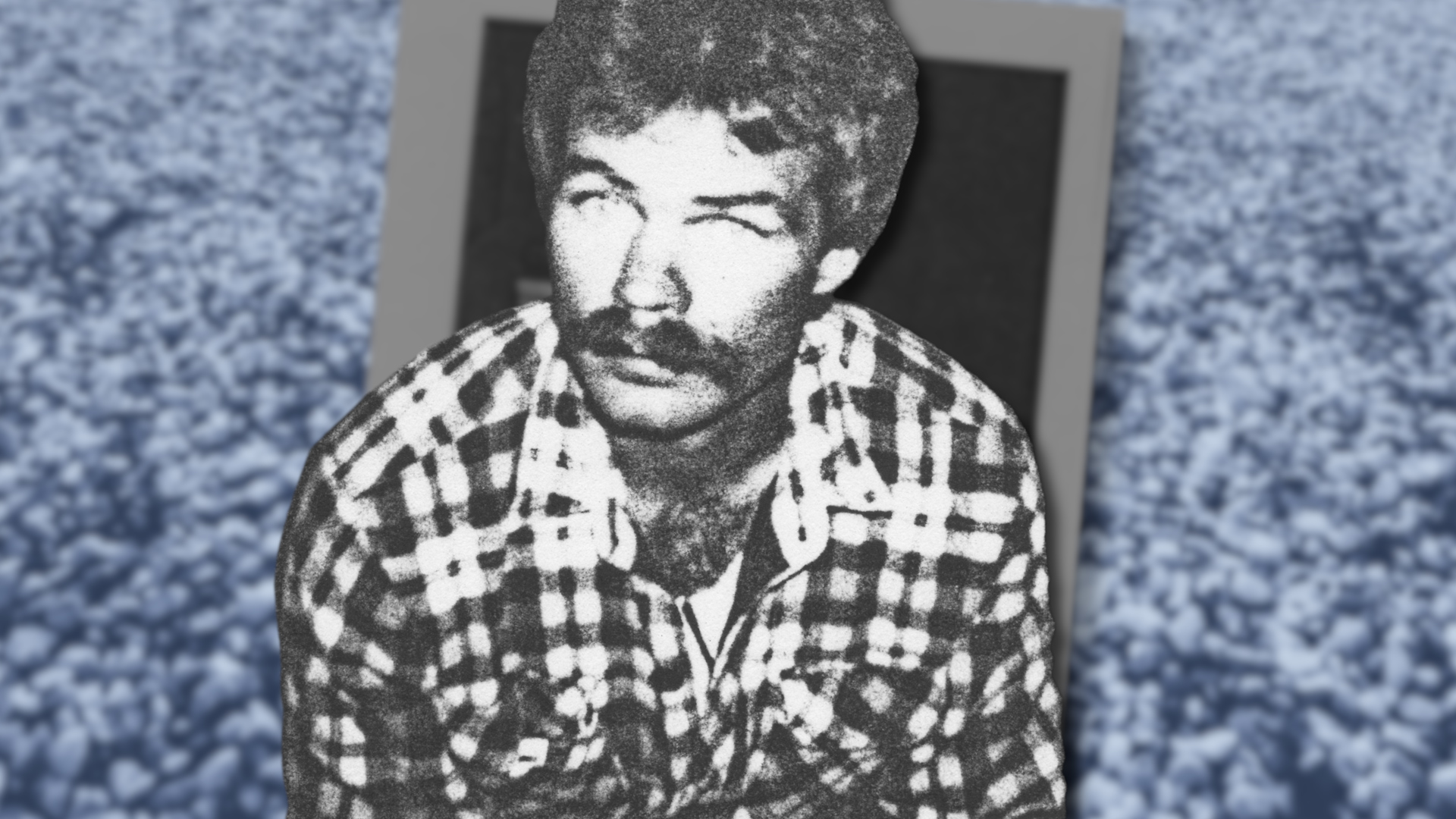

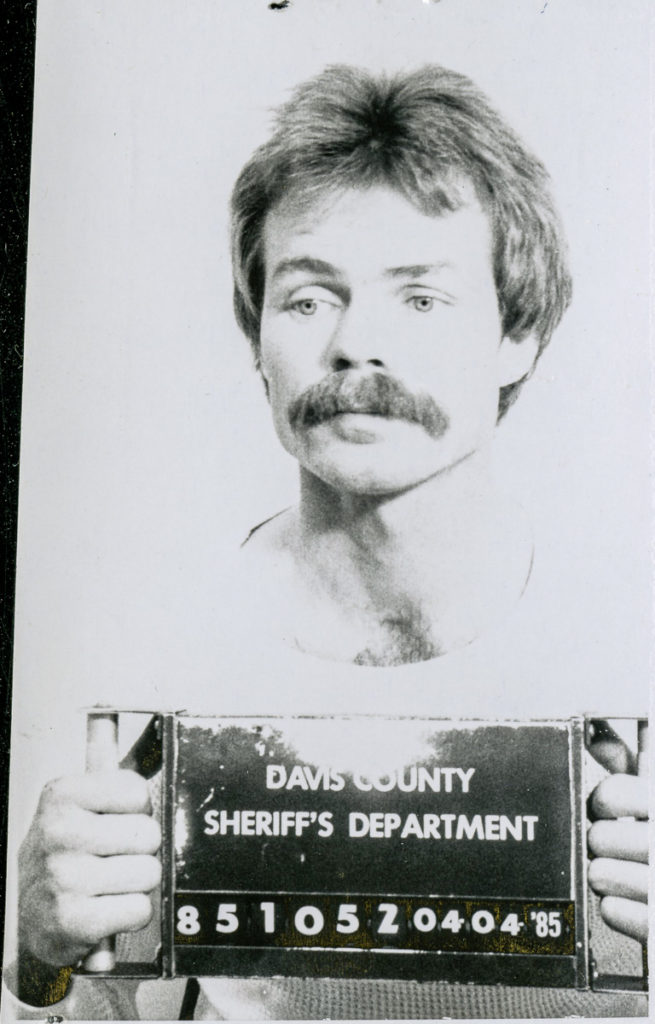

Douglas Lovell returned to the Utah State Prison in January of 1986, following four short years of freedom spent with his wife, Rhonda Lovell.

His earlier stay there, from 1979 to 1982 on an aggravated robbery conviction, had ended early thanks to a show of leniency from the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole. The board had released Doug after he’d served just two-and-a-half years on a sentence of five years-to-life. The board had also seen fit to terminate his parole in August of 1983, effectively ending his post-release supervision.

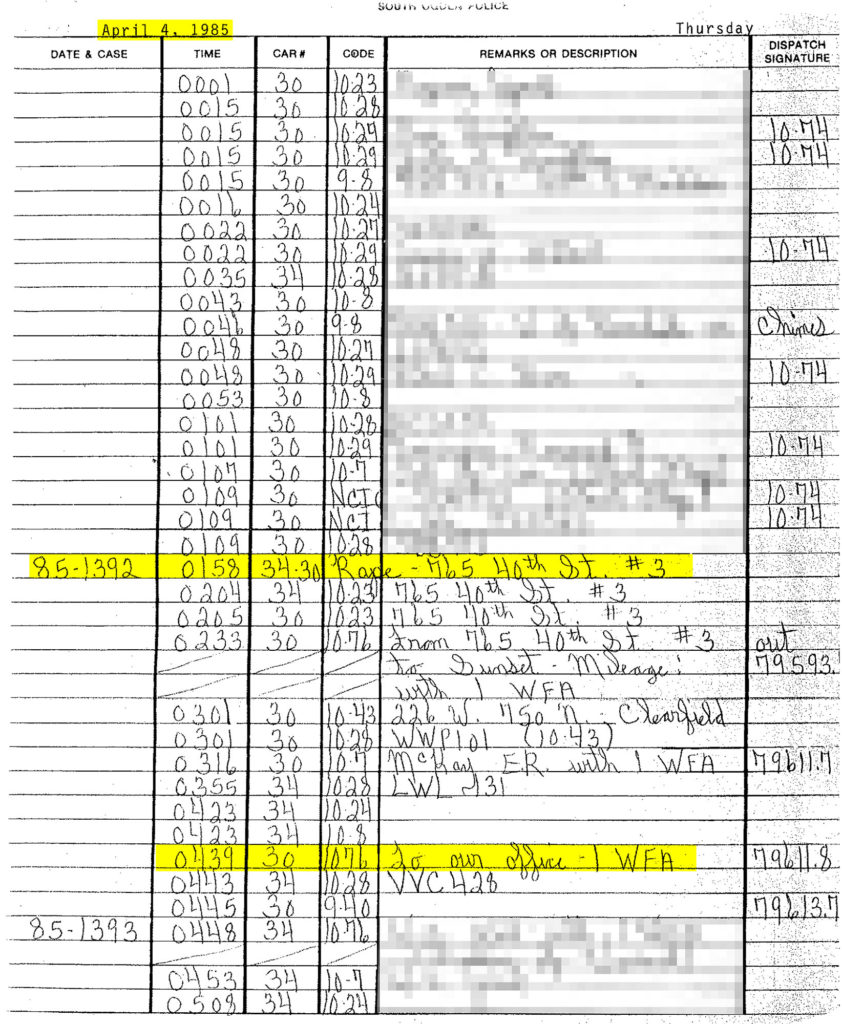

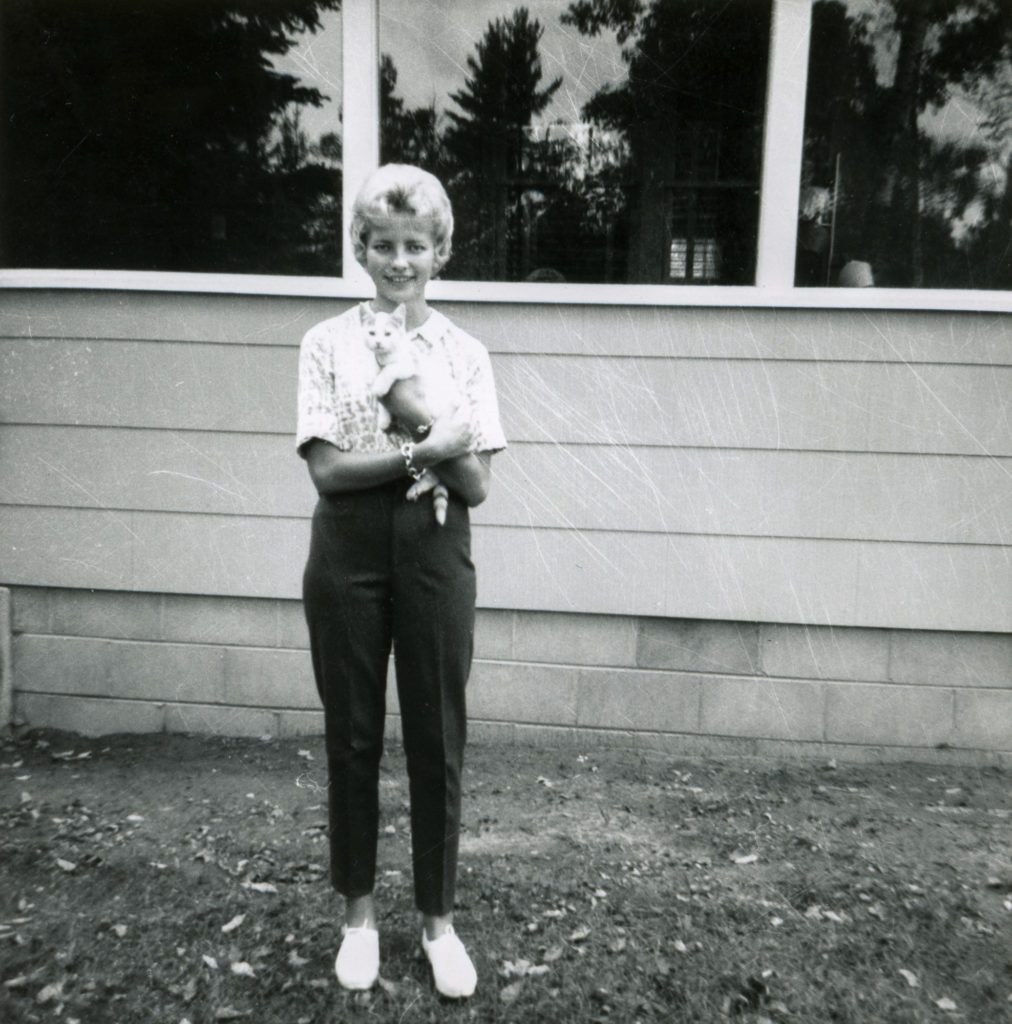

Less than two years later, Doug had followed Joyce Yost home from a club, kidnapped and sexually assaulted her.

The sexual assault of Joyce Yost was a different category of crime. The sex offense carried a similar sentence of five-to-life, but with the added wrinkle of a 15-year minimum mandatory. This meant no amount of mercy from the parole board would end Doug’s time in prison early. His only hope for an early release would be to win an appeal of his conviction, something his attorney hoped to secure by characterizing the attack on Joyce as a “garden variety rape.”

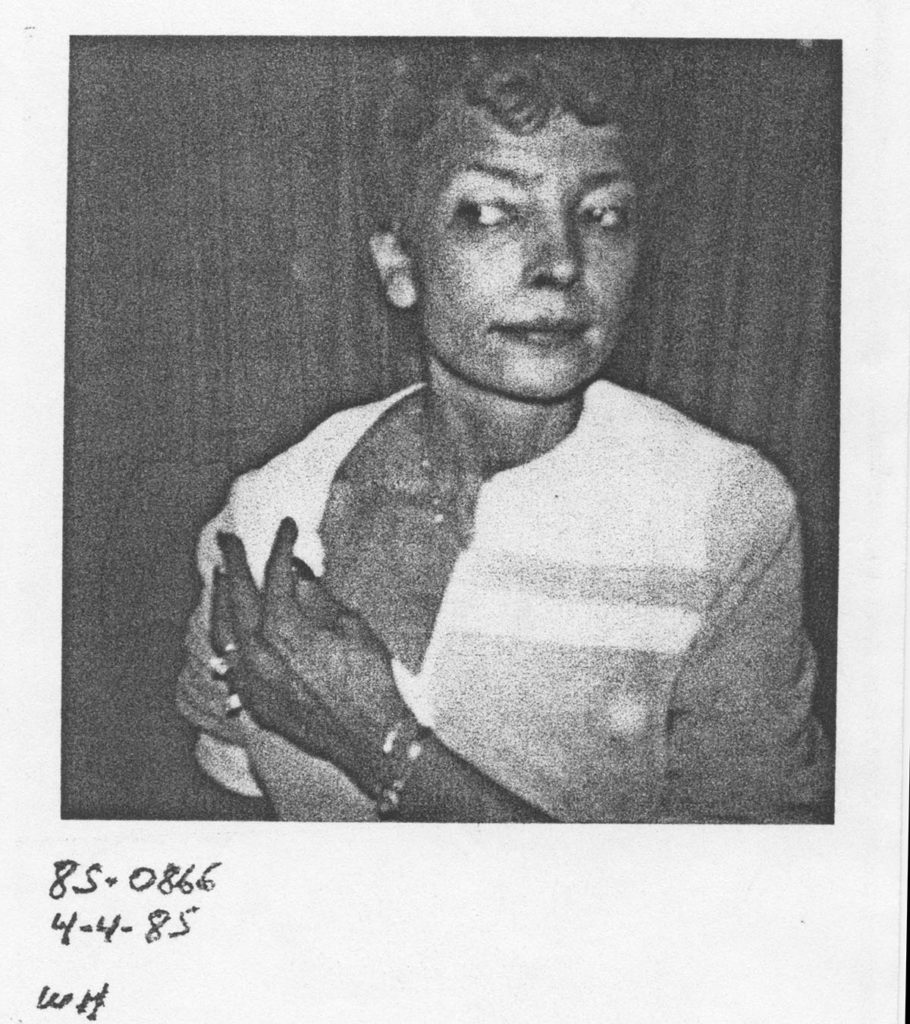

Rhonda Lovell

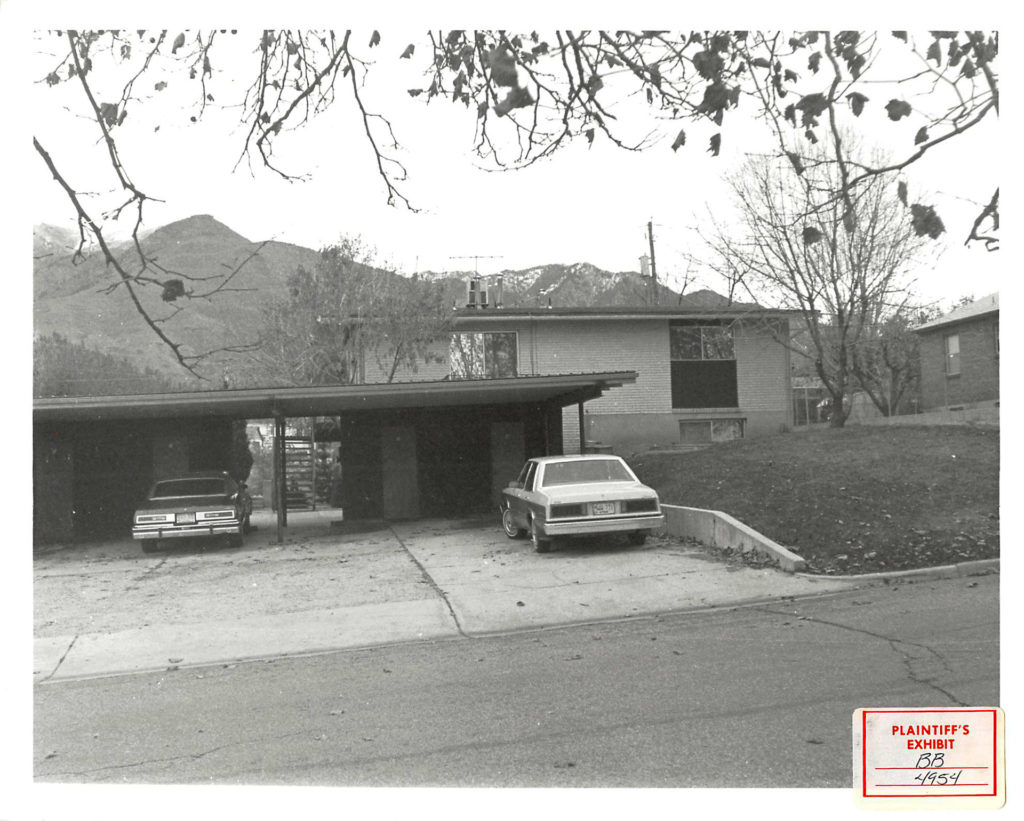

South Ogden police believed Doug had taken Joyce’s life to prevent her from testifying at the rape trial, but they’d been unable to prove it by that point in 1986. However, with Doug at the outset of a lengthy prison stay, the detectives were able to turn their eyes to his wife, Rhonda Lovell.

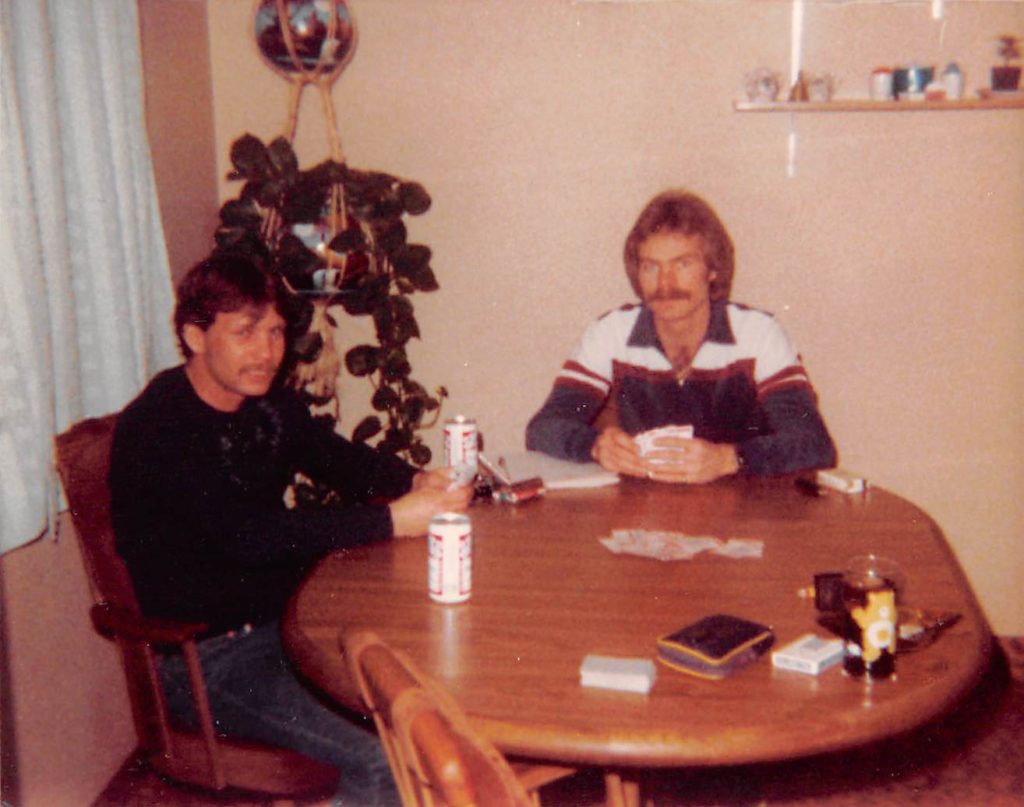

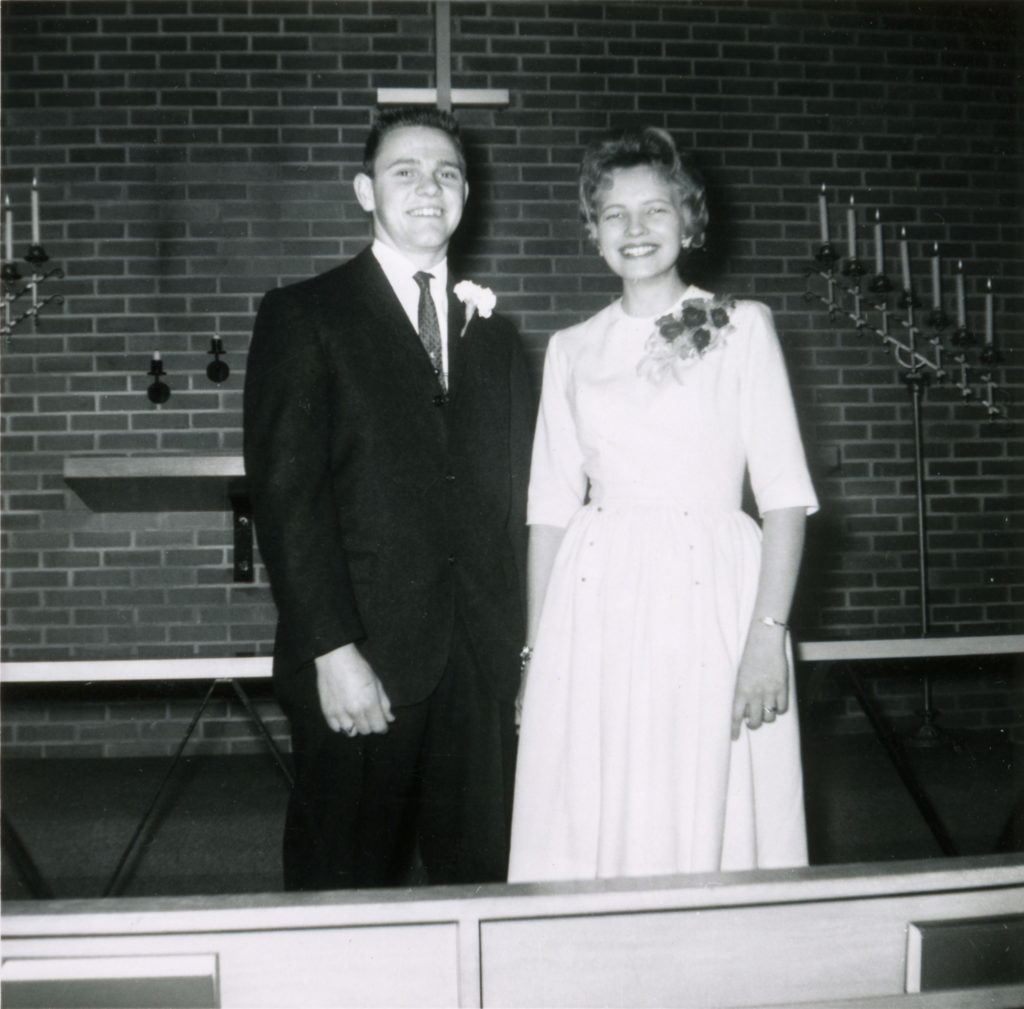

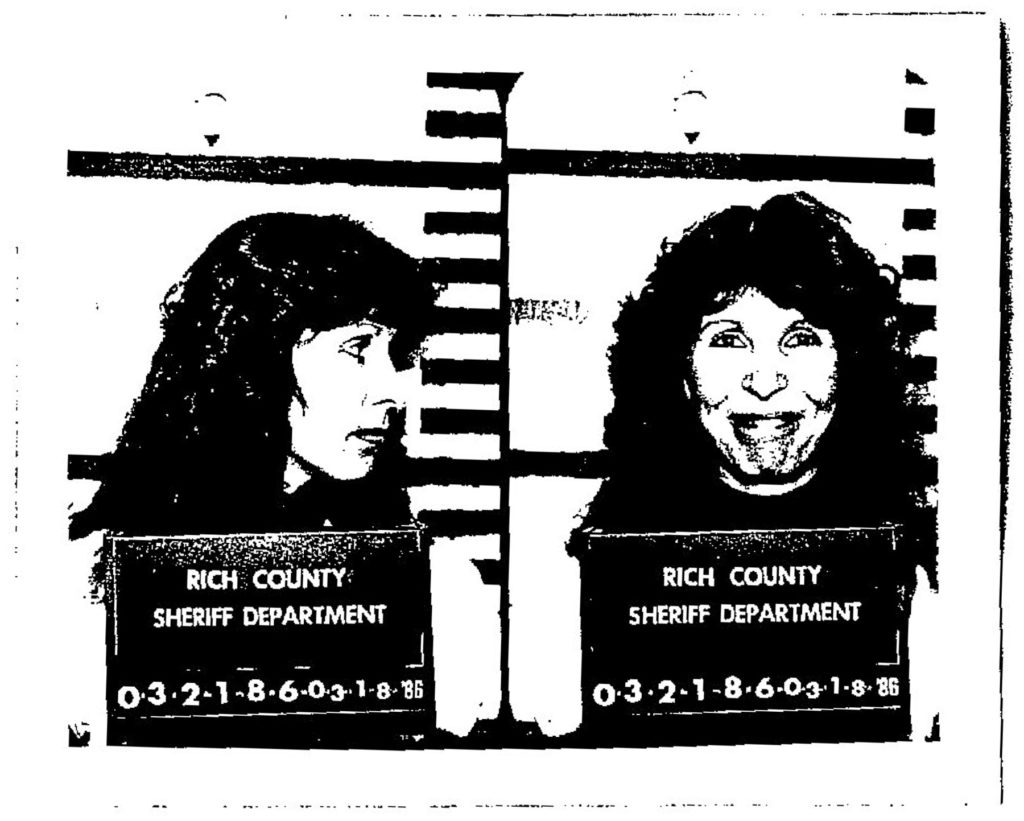

Doug Lovell and Rhonda Buttars had married two years earlier, in January of 1984. They’d conceived a son in late 1985, during the lead-up to the rape trial. Rhonda was still pregnant when, in March of 1986, South Ogden police sergeant Brad Birch arrived at her work bearing an arrest warrant.

Brad was at that time acting as lead investigator on the Joyce Yost disappearance. The warrant he brought with him to Rhonda’s office did not deal with Joyce’s case, though. It instead listed a charge of taking wildlife out of season, or poaching.

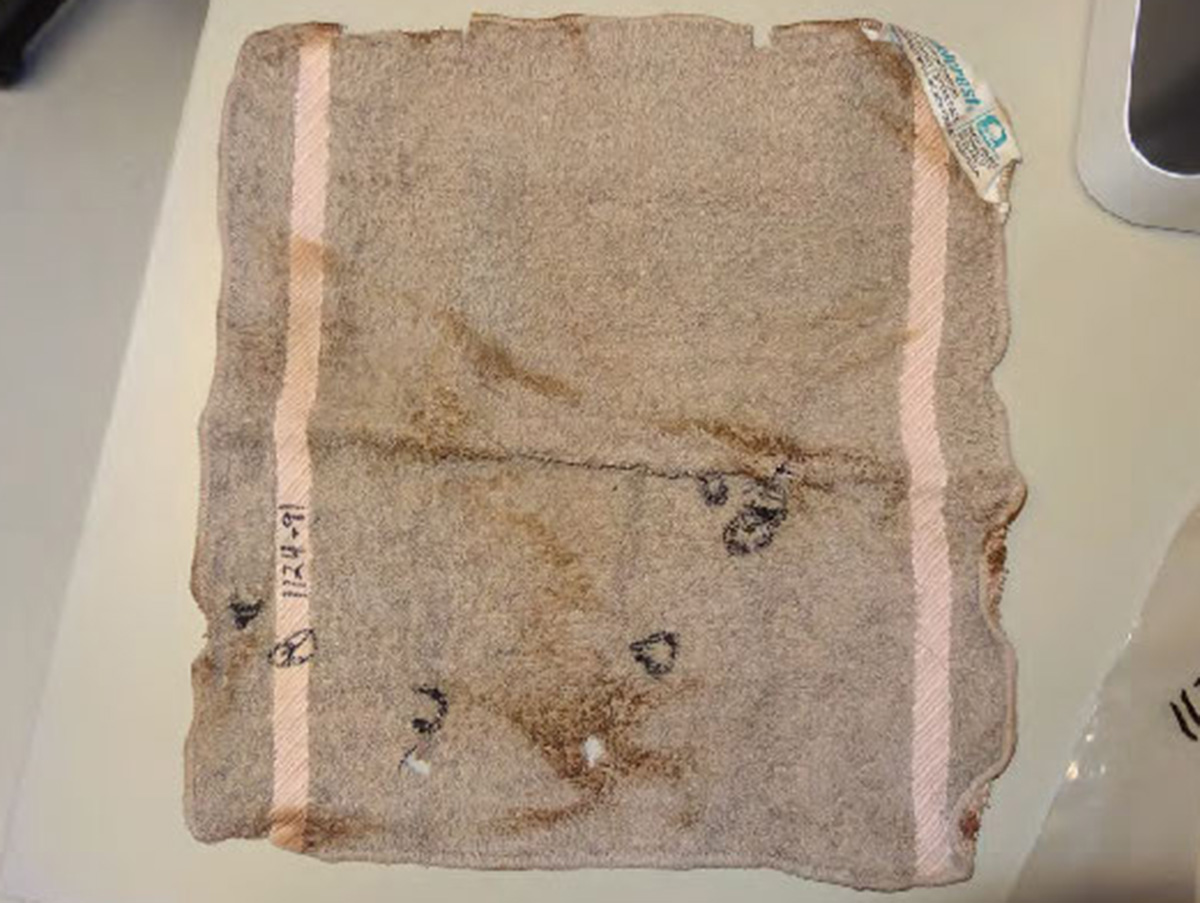

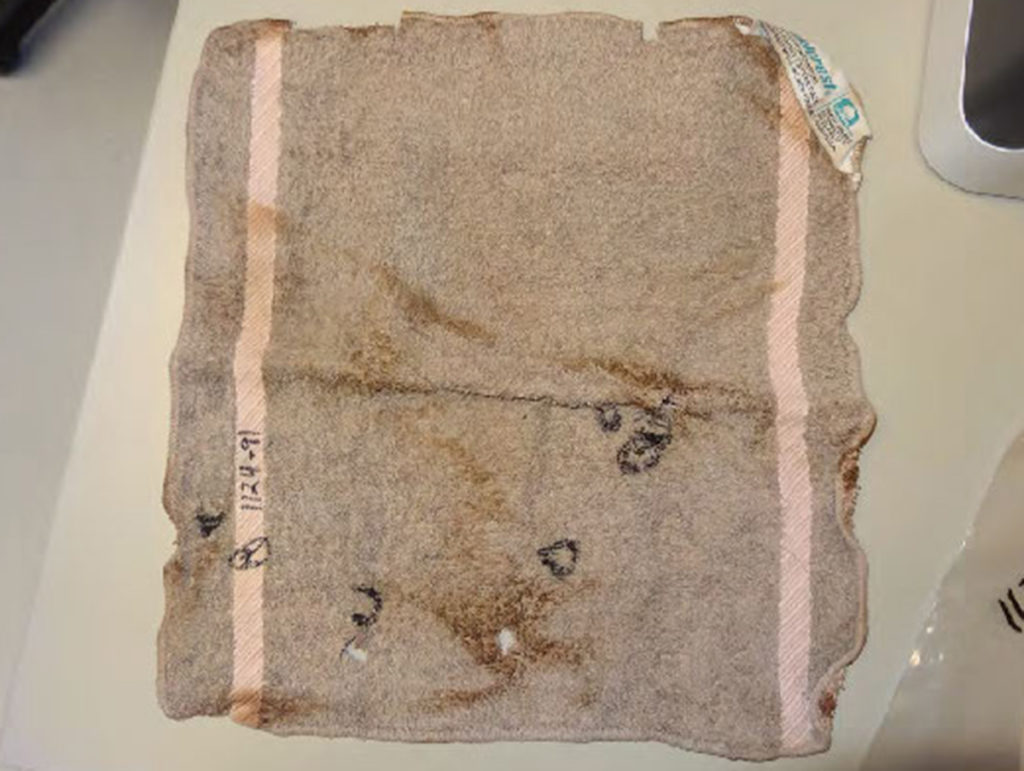

Brad had discovered that a fish and game officer had encountered Doug and Rhonda Lovell in the Monte Cristo Range east of Ogden the prior autumn, after Joyce Yost had disappeared but prior to Doug’s conviction in the sexual assault case.

Poaching stop at Monte Cristo

The Monte Cristo region of northern Utah was a popular spot for summer camping, fall leaf peeping and winter snowmobiling. It’s frequented in the autumn months by hunters who seek deer and elk that spend time in the uplands.

A state highway crossed the southern end of the range, connecting the rural communities of Huntsville on the west and Woodruff on the east. Monte Cristo’s popularity with hunters meant that highway corridor also drew significant attention from the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, which patrolled the area in search of poachers.

One such officer had come across Rhonda Lovell sitting by herself in a vehicle on a snowy day in late 1985. He had stopped to talk with her and Rhonda had reportedly told the wildlife officer she was traveling alone.

A short time later, the same officer had observed Rhonda’s vehicle coming down the highway eastbound toward Woodruff. There appeared to be a second person with her. The officer stopped the vehicle and questioned Rhonda a second time. The man with her, she had supposedly said, was just a hitchhiker.

This seemed unlikely. Utah State Highway 39 was not a thoroughfare where pedestrians would often thumb rides. In fact, the man had not been a hitchhiker. The man with Rhonda during her second conversation with the wildlife officer was her husband, Doug Lovell.

The lost records

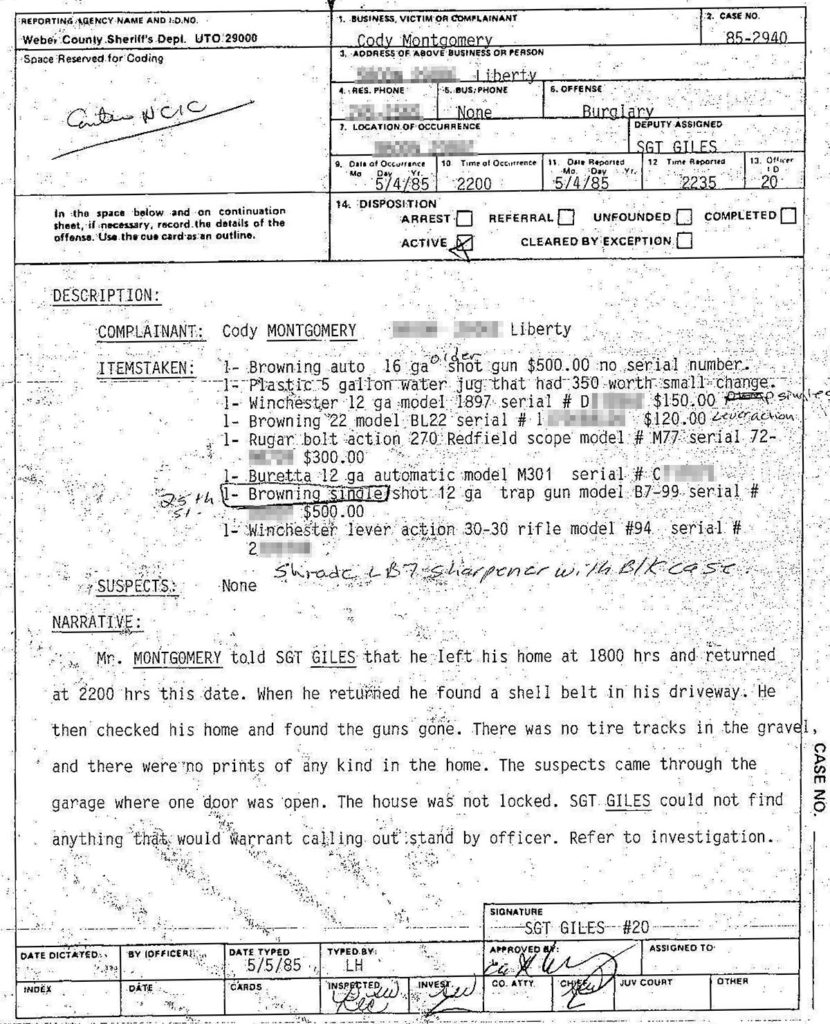

The date of the encounter on Monte Cristo is not clear from available records. Some time passed between that day and the date when the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources is said to have discovered an animal carcass which had been poached in the Monte Cristo region. The agency screened charges with a prosecutor in Utah’s Rich County, which led to the filing of charges against Doug and Rhonda Lovell.

The charging documents filed in Rich County Circuit Court are no longer available, having at some point in the 35 years since been purged in accordance with state record retention rules. The probable cause statement which would have included an outline of the factual basis for the charges has not been preserved by the court.

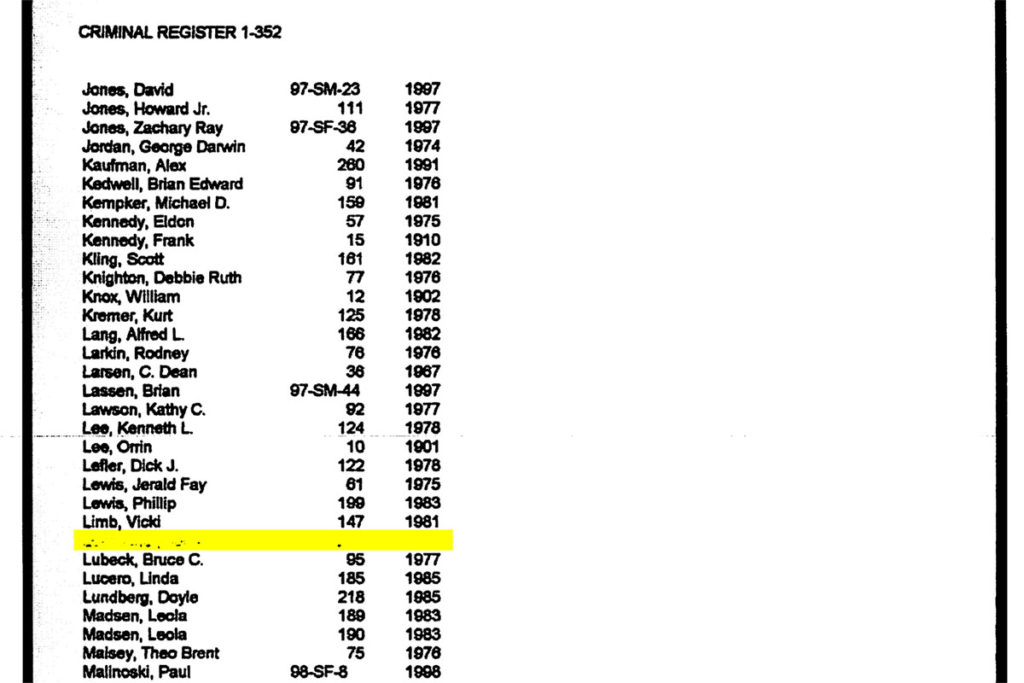

In response to a public records request from the Cold team, Rich County Attorney Ben Willoughby said the county had only kept a scanned copy of a register of court cases from that time period. The document, titled Index to Criminal Register of Actions 1896 to 1998, included names, case numbers and years for criminal cases filed in the county’s court.

“However, it does not contain a case file for Rhonda Lovell,” Willoughby wrote in an emailed response to Cold’s record request. “The spot in the index where her case should be alphabetically referenced appears to have been whited out prior to being scanned.”

Hunt for the Wildlife Resources officer

A subsequent public records request to the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources likewise failed to uncover any paperwork underlying the arrest warrant, though that’s not unusual considering the age of the case, the lack of computerized record systems at the time and government rules which allow for the destruction of some paper records on a prescribed schedule.

The Cold team made contact with several current and former DWR employees in an attempt to identify the wildlife officer who encountered Rhonda Lovell in 1985. Those included sworn law enforcement officers known to have participated in poaching patrols of the Monte Cristo region in 1985. None specifically recalled being involved with the case or suggested who might have been.

[Editor’s note: After this article was first published, a source came forward and stated the wildlife officer who’d stopped Rhonda Lovell was conservation officer LaVon Thomas. Thomas is deceased.]

It remains unclear how word of Doug and Rhonda Lovell’s encounter with the wildlife officer made its way to South Ogden police or why Brad Birch, and not the wildlife officer, served the arrest warrant on Rhonda on March 19, 1986. However, Joyce Yost’s daughter Kim Salazar said she was aware of the plan to arrest Rhonda before it occurred.

“I know that they were trying to get information [about Joyce] so they used this poaching as a way to talk to Rhonda, to put some pressure,” Kim said.

Rhonda Lovell’s interview

Brad brought Rhonda to South Ogden police headquarters and sat her down in an interview room. He read Rhonda her Miranda rights. Then he and another detective, Terry Carpenter, began to ask questions.

“They kept saying, ‘If you know something [about Joyce Yost], we’ll let you go if you tell us. … Otherwise we’re going for a long ride.’ I said, ‘Well let’s go.’”

Rhonda Buttars (Lovell), on her 1986 interview with South Ogden police

Both Brad and Terry filed written reports following their interview with Rhonda. The reports said she denied having knowledge of or part in any poaching scheme. Rhonda reportedly told the detectives that Doug had been out of the car defecating when the wildlife officer had first approached her. She’d felt embarrassment over this, which is why she had instead claimed to be alone. She did not have an explanation for why she had later told the same officer Doug was a hitchhiker.

The reports said Rhonda claimed to have been headed to Woodruff with Doug at that time for a snowmobiling outing with friends. But she declined to identify those friends, saying she didn’t want to get them involved.

The detectives also took the opportunity to question Rhonda about the disappearance of Joyce Yost. Rhonda, the reports said, claimed no knowledge of what had happened to Joyce. She denied Doug’d had anything to do with it.

“Rhonda asked some questions about the trial which were answered by Sgt. Birch,” Terry’s report read. “Rhonda was asked if Doug had any firearms. She stated that he only had one rifle that she was aware of. That being a Weatherby 300.”

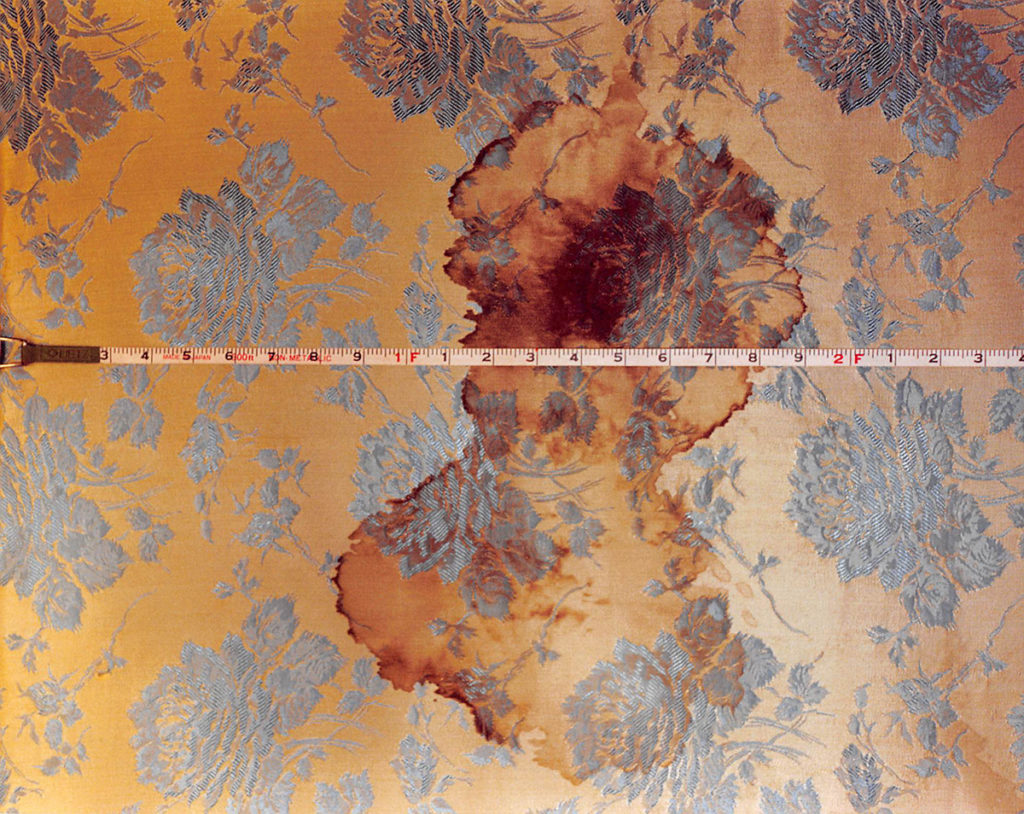

This was untrue, as Rhonda had been with Doug and his friend William “Billy Jack” Wiswell when they had buried a cache of stolen guns behind a cabin in Utah’s Deep Creek Mountains. The South Ogden detectives were unaware of that fact at the time.

Rhonda Lovell’s stay in jail

At the conclusion of the interview, Brad and Terry informed Rhonda they would be taking her to the Rich County jail in Randolph, Utah for booking on the poaching warrant. They allowed her to make child care arrangements for her daughter before starting the 100-mile drive.

“Rhonda was seven or eight months pregnant and so we transported her and tried in about every way to help her as much as we could,” Terry told me in an April, 2021 interview.

Terry recalled Rhonda being cordial, in spite of the circumstances. His 1986 report had described her as “very sociable and willing to talk about anything else.”

Rhonda did not crack under the pressure. Her husband acted as her lawyer when their case went before a judge the following May. Doug Lovell succeeded in having the charges dropped.

An anonymous call

Doug and Rhonda Lovell’s encounter with the wildlife officer would take on new significance for investigators a year later. On April 3, 1987, a man called police in Roy, Utah and reported finding a body in the mountains near Causey Dam. In a subsequent call to the Weber County Sheriff’s Office, the anonymous caller said he’d observed a woman’s purse next to the body.

Causey is accessed by way of the same highway Doug and Rhonda had been traveling at the time of the poaching stop at Monte Cristo.

Numerous searches of the area around Causey failed to turn up any human remains. The anonymous caller was never identified. Detectives who investigated the report believe the man was being honest but were unable to recover the body without his further assistance.

Hear the the anonymous caller’s voice in episode 5 of Cold: Garden Variety

Episode credits

Research, writing and hosting: Dave Cawley

Audio production: Nina Earnest

Audio mixing: Trent Sell

Additional voices: Saige Miller (as Rhonda Lovell), Ethan Millard (as Archie Smith), Alex Kirry (as Murray Miron)

Cold main score composition: Michael Bahnmiller

Cold main score mixing: Dan Blanck

KSL executive producers: Sheryl Worsley, Keira Farrimond

Workhouse Media executive producers: Paul Anderson, Nick Panella, Andrew Greenwood

Amazon Music team: Morgan Jones, Eliza Mills, Vanessa Rebbert, Shea Simpson

Episode transcript: https://thecoldpodcast.com/season-2-transcript/garden-variety-full-transcript/

KSL companion story: https://ksltv.com/460854/anonymous-call-may-have-led-to-joyce-yosts-body-near-causey/

Talking Cold companion episode: https://thecoldpodcast.com/talking-cold#tc-episode-5