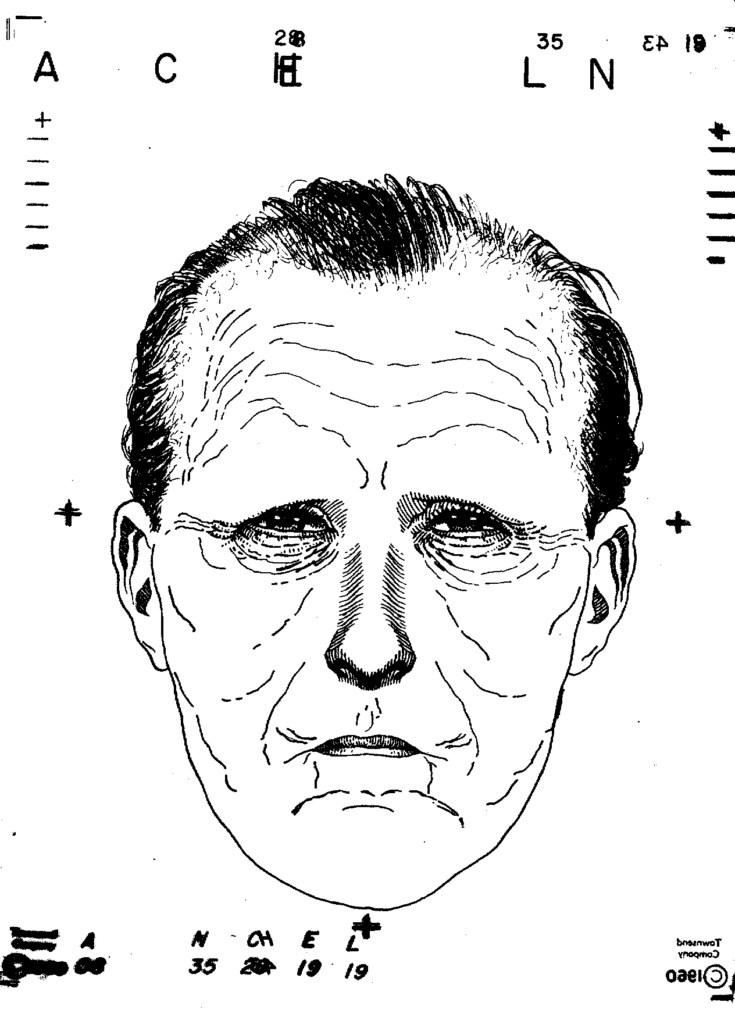

Dave Cawley: Serial killer Ted Bundy spent years denying what he’d done. From his initial arrest in Utah…

Reporter (from November 21, 1975 KSL TV archive): You said you were surprised when you went to jail. For better or for worse?

Ted Bundy (from November 21, 1975 KSL TV archive): Hey listen, uh, we do have to go. Surprised? I don’t know. I didn’t know what to expect. I’ve never been in a jail before, never been arrested before.

Dave Cawley: …to Ted Bundy’s murder convictions in Florida…

Ted Bundy (from July 24, 1979 KSL TV archive): Police officers, they want to solve crimes and sometimes I don’t think really, they really try to think things through. … And they’re willing to take the convenient alternative. And the convenient alternative is me.

Dave Cawley: …Ted Bundy maintained his innocence. But Bundy wasn’t innocent.

John Hollenhorst (from January 24, 1989 KSL TV archive): The Ted Bundy story is in part a historical odyssey stretching thousands of miles from one corner of the country to the other. It’s part crime drama, spanning most of two decades.

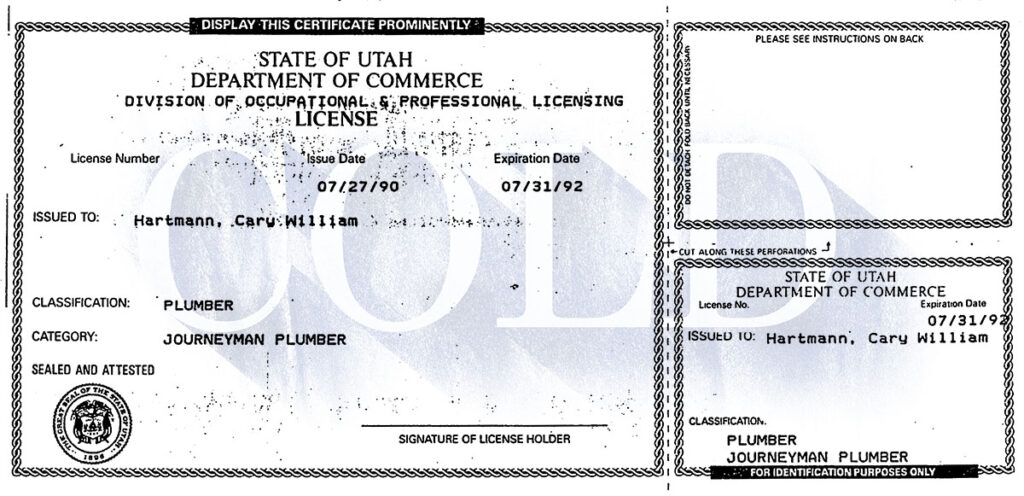

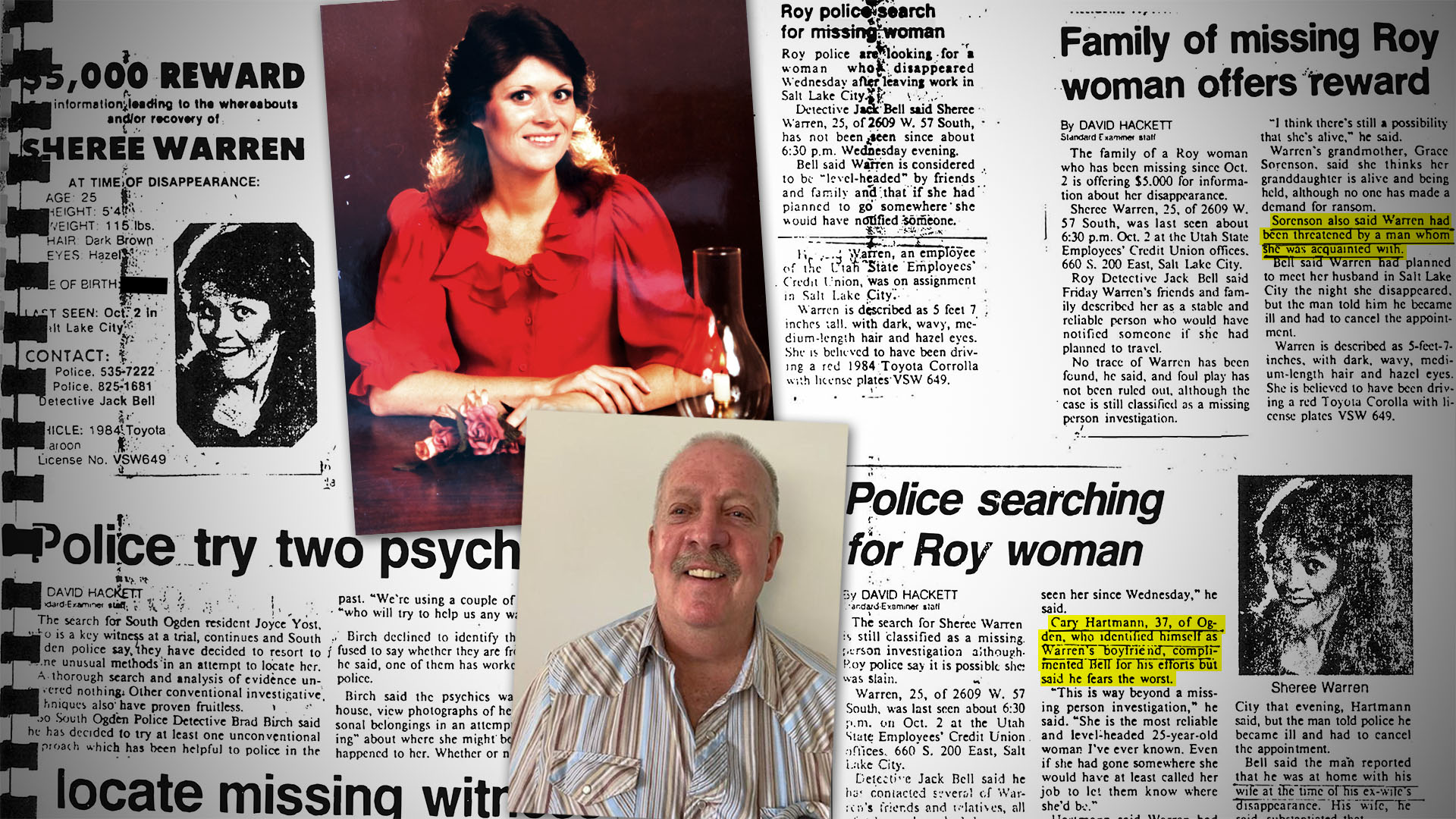

Dave Cawley: In Cold season 3, we heard how Cary Hartmann, one of the two suspects in the disappearance of Sheree Warren, had been fascinated by Ted Bundy.

John Hollenhorst (from January 24, 1989 KSL TV archive): But most of all, it’s a psychological mystery about a man who lived in two worlds: an everyday world of shining opportunity and a dark world of madness and violence.

Dave Cawley: Ted Bundy was a charismatic young law student with a promising future in politics when he moved from Washington state to Utah at the end of summer in 1974. At that same time, police in and around Seattle were looking into a string of disappearances and deaths.

John Hollenhorst (from January 24, 1989 KSL TV archive): The press began talking about a lookalike killer who seemed to select women simply because they were young and pretty.

Dave Cawley: By his own later admission, Bundy killed at least 30 women during the 1970s. To this day, many remain unidentified and in some cases, were never located.

Bundy’s final murders, in Florida, landed him on death row in 1979. A flurry of legal appeals followed but by 1986 it appeared Bundy would be executed. As the scheduled date approached, investigators from across the country traveled to Florida in the hopes of interviewing him about their unsolved cases.

Richard Bingham (from February 5, 1986 KSL TV archive): Here in Utah he’s a suspect in the murders of Melissa Smith and Laura Aime. Also the disappearance of Nancy Wilcox and Nancy Baird. Salt Lake County Sheriff Pete Hayward has been involved in the case from the beginning.

Pete Hayward (from February 5, 1986 KSL TV archive): There’s no doubt in my mind that he’s responsible for the Smith girl and the Aime girl that was found in American Fork Canyon. Uh, we have two other girls that we feel strongly that he’d have to be considered as a prime suspect in and that would be the Wilcox girl and a young lady that was taken out of a gas station up in, I believe it was Layton.

Dave Cawley: It’s that last young woman we’re going to focus on in this episode. Bundy was only willing to talk if it played to his advantage. He intended to barter information about his crimes as a last resort to stave off execution. But he didn’t have to do that in 1986 because the courts granted him a reprieve.

Pete Hayward (from June 27, 1986 KSL TV archive): Bundy at that time made the comment that it wouldn’t be in his best interest to talk to us at this time. But did not say that he wouldn’t talk to us at all.

Dave Cawley: That narrow escape from the electric chair only added to the Bundy mystique.

Mary King (from July 2, 1986 KSL TV archive): Florida State Prison.

John Hollenhorst (from July 2, 1986 KSL TV archive): Bundy’s notoriety has prompted many hundreds of phone calls to the prison in recent weeks, mostly from women.

Mary King (from July 2, 1986 KSL TV archive): They want to talk to him, or they want to know his address so they can write to him, or they want to congratulate on us on having nerve enough to try to burn him.

Dave Cawley: This building of a serial killer into a cultural icon was gross then and it remains so today. And I’m hesitant to play into that by talking about Ted Bundy in this podcast. But it’s important to understand just how pervasive Bundy was in the minds of police and the public during the late 1970s and through the 1980s for the story you’re about to hear.

Florida scheduled a new execution date for Ted Bundy, in January of 1989. This time, Bundy’s legal challenges were swept aside. And so, with no other option to forestall his appointment with the electric chair, Bundy started to talk. He spoke with investigators in the hopes of delaying his impending death.

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Ok, I’ve turned the recorder on.

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): We’ll do what we can.

Dave Cawley: That’s how a detective named Dennis Couch from the Salt Lake County Sheriff’s Office in Utah ended up sitting down with Ted Bundy on January 22nd, 1989. This audio comes from that interview.

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): That’s my first and foremost reason for being here, for those three girls that are missing and—

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): And some more.

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): From Utah?

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Yeah.

Dave Cawley: The tape recording of this interview is sometimes difficult to understand. But during their 90 minutes together, Bundy told detective Couch he was responsible for five murders in Utah.

Joel Munson (from January 24, 1989 KSL TV archive): Along with the Kent and Wilcox murders, Couch says Bundy gave useful information that should help investigators solve the murders of Melissa Smith and Laura Aime.

Dave Cawley: Police had already found two of the bodies: those of Melissa Smith and Laura Aime. Bundy tried to tell them where they might find two others: Debra Kent and Nancy Wilcox. But that left one victim unidentified.

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Sorry—

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): No, that’s ok.

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): —you’re catching me when you are—

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Yeah, I’m just getting quite anxious myself, y’know.

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): I hear you, I hear you. We’re all up against some deadlines.

Dave Cawley: I don’t bring all this up simply to relive the past. I want you to hear what Ted Bundy said when detective Dennis Couch asked him about a specific unsolved case.

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Further up was Nancy Baird who worked at a gas station. July 4th.

Dave Cawley: The disappearance of Nancy Perry Baird.

Joel Munson (from January 24, 1989 KSL TV archive): But Couch did not get the answer he was hoping for regarding another Utah murder, that of Nancy Baird of Layton. Bundy insisted he had no part in that killing.

Dave Cawley: Nancy Baird’s name might sound familiar. It came up in passing during our discussion of the Sheree Warren case in Cold season 3, but I couldn’t take too deep of a diversion into it then. So, we’re going to do that now.

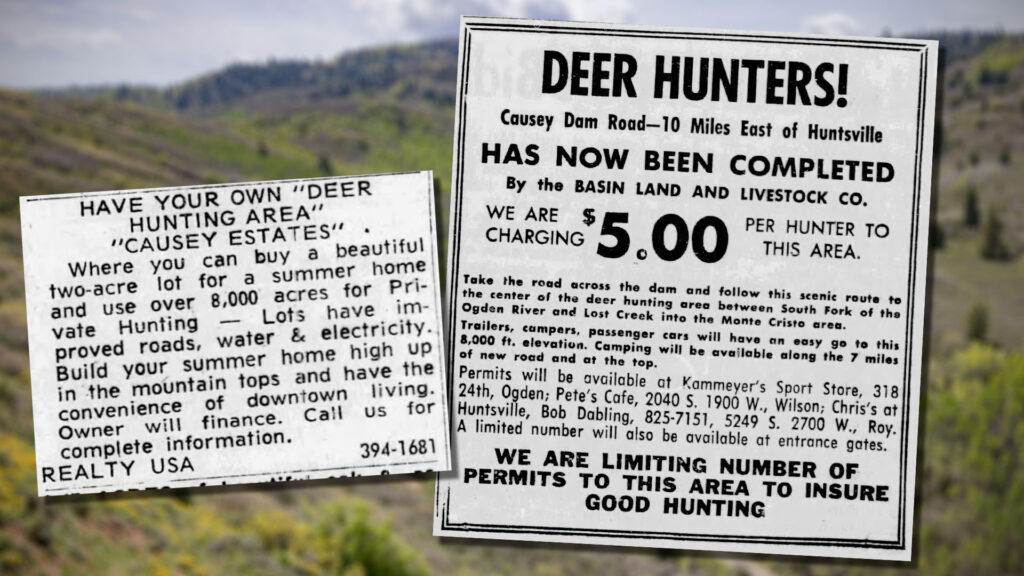

Nancy Baird vanished from a gas station where she worked in East Layton, Utah on the evening of July 4th, 1975. In the years that followed, many people came to the conclusion Ted Bundy abducted and killed her.

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Do you recall, umm, what type of place it was she was working at or where it was located? On which highway?

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): No, I didn’t have anything to do with that.

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Nancy Baird?

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): No.

Dave Cawley: Even today, Nancy Baird’s name appears in online lists of suspected Ted Bundy victims. Many of Nancy’s own relatives even believe Bundy killed her. But Bundy said he wasn’t responsible.

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Well that, no. I don’t know anything about that disappearance.

Dave Cawley: Nancy Baird’s body has never been found. The detective who interviewed Bundy, Dennis Couch, is retired now. I’ve talked to him. He declined my request for a recorded interview. But he told me he hadn’t been personally familiar with the details of the Nancy Baird case back in 1989, when he’d questioned Bundy. Nancy Baird’s disappearance had happened in a different county and deputies there had just asked detective Couch to show Nancy Baird’s picture to Bundy and ask what he’d done to her. Bundy’d seemed not to recognize the photo, or the name Nancy Baird.

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Can we go back to Nancy Baird? You, you indicated that—

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Now, Nancy Baird, who’s that?

Dave Cawley: Days after the interview, on January 24th, 1989, Florida executed Ted Bundy by electrocution.

John Hollenhorst (from January 24, 1989 KSL TV archive): The prison was shrouded in darkness when smoke began to pour from the backup electrical generator used during executions. By then, demonstrators were arriving by the hundreds to watch the spectacle of a killer’s death.

Demonstrator (from January 24, 1989 KSL TV archive): I would like to be right in there and see him fry.

Dave Cawley: Public attitudes about Ted Bundy were broadly negative, for obvious reasons. Yet many people who hated Bundy found themselves fascinated by the story. Bundy embodied a strange duality: an outward charisma protecting a depraved core. His execution was a major news event.

John Hollenhorst (from January 24, 1989 KSL TV archive): The demonstrators invaded the media center. Some, wearing costumes, waving frying pans, sporting gruesome slogans. Songs about the despised serial killer added to the carnival atmosphere.

Crowd (from January 24, 1989 KSL TV archive): (Singing) Now we’re all ecstatic Ted Bundy is dead.

John Hollenhorst (from January 24, 1989 KSL TV archive): So the Bundy saga is over now, except those who will pick through it to figure out what it all means.

Dave Cawley: “What it all means.” It means a lot for the still-unsolved disappearance of Nancy Baird. In season 3 episode 6, I shared the story of a jailhouse informant who claimed Cary Hartmann had been seeing Nancy Baird around the time she disappeared. That informant was probably not credible, and I’ve not found any direct evidence linking Cary Hartmann to Nancy Baird.

But that story thread started me down a new line of investigation into Nancy Baird’s case. In the process, I obtained never-before-released case files. I spoke to relatives, witnesses and investigators. And I came to the conclusion Ted Bundy was probably telling the truth when he said he didn’t know anything about the death of Nancy Baird.

But Ted Bundy cast a long shadow and because of it, no one did any significant work on Nancy Baird’s case for decades.

This is a bonus episode of Cold, season 3: The Convenient Alternative. From KSL Podcasts, I’m Dave Cawley.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: The 4th of July fell on a Friday in 1975. It marked the start of a long, hot holiday weekend. Many Utahns hit the road, hoping to escape the heat by heading to the mountains. Denzle Williams, on the other hand, spent the day at home with his wife and kids. He lived in a town called Kaysville, midway between the cities of Salt Lake and Ogden.

A little after 5 p.m. on the afternoon of July 4th, Denzle drove from his house to a gas station a couple of miles up the road, in the neighboring town of East Layton.

David Williams: We had to get gas for a rototiller.

Dave Cawley: That’s the voice of Denzle’s son, David Williams. He was a few weeks shy of his 14th birthday when he accompanied his dad on this errand in 1975. They drove together to the gas station which sat alongside U.S. Highway 89.

David Williams: The Fina station, I remember, it was, y’know, green and white.

Dave Cawley: Denzle pulled his Dodge Dart to a stop next to one of the pumps. David stepped out onto the blacktop, followed by his little sister, nine-and-a-half-year-old Jana. David and Jana told me as kids, the Fina station was a favorite stop for…

Jana Williams Grow: Pop and—

David Williams: Chips.

Jana Williams Grow: —chips and candy.

David Williams: Candy.

Dave Cawley: Jana dashed into the store, while David retrieved a small gas can from the car’s trunk. He filled it, then handed the hose off to his dad. Denzle started filling the car. He planned to take his son David golfing the next morning and wanted to start their trip to the golf course with a full tank.

David Williams: I was excited because I was a teenager able to go play golf with my father at that time, because we didn’t get out and do that very often together.

Dave Cawley: Denzle gave David his credit card, and told him to go inside and pay for the gas. This was long before technology allowed for pay-at-the-pump. David followed his little sister Jana through the door into the Fina station’s convenience store.

Dave Williams: As, as you walk in there were, I recall, two men at the end of the counter talking to Nancy.

Dave Cawley: Nancy Perry Baird, the clerk, was 23 years old. She was petite, standing only five-foot-two, and had long, strawberry-blonde hair. She appeared younger than her age and she caught David’s eye.

Dave Williams: I believe she had a halter top on and shorts. I’m like “oh, she’s cute.”

Dave Cawley: David stood there for a moment, holding his dad’s credit card, looking at the two older guys who were talking to Nancy.

David Williams: I didn’t want to interrupt this conversation they were having. The one guy, he did have kind of longer hair. Umm, like a, a Levi jacket that was faded. I think they both had longer hair.

Dave Cawley: Jana, meanwhile, wandered down between the shelves of candy, toward a case of chilled drinks.

Jana Williams Grow: And I do remember walking through the store and I just remember seeing one man.

Dave Cawley: After a moment, Nancy took notice of David. She paused her conversation with the two men at the counter and took the credit card from David.

David Williams: And as I was doing the transaction they were just kind of there.

Dave Cawley: Nancy placed the card on a device known as an “imprinter.”

David Williams: She takes it, puts it on a little uh, yeah machine.

Dave Cawley: In the days before tap-to-pay or even magnetic stripes on credit cards, clerks used imprinters—or click-clacks as they were sometimes called—to make physical rubbings of the raised letters and numbers on each customer’s card.

David Williams: And then she writes down how much it was. And if you bought anything else, she would add that to it. And then you had to physically sign the paper. And she gave you a copy and then she kept a copy.

Dave Cawley: As Nancy imprinted the card for David, Jana approached her brother carrying a bottle of raspberry soda.

Jana Williams Grow: I was getting a drink. You wouldn’t pay for it.

David Williams: Nope.

Jana Williams Grow: So I had to pay for my own. And I remember she was a very nice clerk.

Dave Cawley: David headed back outside into the heat with the credit card receipt, while Jana handed Nancy Baird the chilled bottle of soda. The total came to 29 cents. Jana counted out her pennies and she only had 28. With a smile, Nancy told her young customer not to worry about the extra cent. She’d take care of it. Jana then followed her brother outside, not realizing she would be the last person known to ever see Nancy Baird.

Except, I can already see the emails and DMs I’m going to receive from people who Google Nancy Baird’s name, then message me to say I’m wrong on this fact. Jana Williams wasn’t the last person to see Nancy Baird, they’ll say. If you look up Nancy Baird on NAMUS, the U.S. government’s missing and unidentified persons database, you’ll read Nancy was last seen by a “patrol officer” 15 minutes before her disappearance. There’s no mention in the database of David or Jana Williams. So which account is correct? They both are, sort of.

East Layton was a town with a population of about a thousand people in 1975. The little bedroom community, speckled with cherry orchards, sat against the foot of the Wasatch Mountains. U.S. Highway 89 crossed through East Layton from north to south, linking it to larger cities nearby.

The highway was the only reason East Layton had any tax base to speak of. There were only three businesses in the town, two of them being gas stations on opposite sides of the highway at a cross street called Cherry Lane. One of those gas stations was the Fina where Nancy Baird worked.

Nancy spent the first part of her life in the nearby city of Ogden. The Perry family moved to East Layton in about 1964. Nancy attended high school in Layton City proper, graduating in the class of 1970.

Toward the end of her senior year, shortly after her 18th birthday, Nancy became pregnant. The father was a young man named Floyd Dee Baird, who was about six months older than Nancy.

Floyd and Nancy married in April of 1970. They welcomed their son that October. The young Baird family spent a few rough years together and ultimately divorced around the start of 1974. Floyd would later tell police he and Nancy remained on good terms after the split, finding they got along better as exes than they had as husband and wife. Nancy maintained custody of their son. She divided her time between caring for him and working to support herself and her child.

Going back through old newspaper archives, I found a help wanted ad for the Fina station from 1973. It advertised an hourly pay rate of $1.70. That’s about the same as a job offering $11.30 an hour in early 2023. Nancy probably made less than that, considering even today U.S. Census Bureau data shows adult women working full-time in Utah earn, on average, only 72% as much as their male counterparts.

And there’s evidence in the record to support the idea Nancy Baird was underemployed. Case files show she told an employment counselor in March of 1975 she felt unhappy and wanted a better opportunity for herself. But that opportunity hadn’t yet materialized when she headed to work at the Fina station on the afternoon of the 4th of July, 1975.

She’d spent that morning with her parents, siblings and son at the house in East Layton where she’d grown up. Just before 3 p.m., Nancy left her four-year-old boy with her parents and drove to the Fina station a mile down the road.

She was scheduled to stay at the Fina until midnight, running the register on what promised to be a busy holiday evening. With any luck, she might catch a glimpse of fireworks out over the valley after dark.

(Sound of distant fireworks)

Dave Cawley: Nancy’d been on shift a couple of hours when, just after 5 p.m., a familiar face came through the door. It belonged to a guy named Dave Anderson, East Layton’s lone full-time police officer. His primary responsibility was writing tickets to lead-footed motorists on the highway. He often parked his patrol car outside the Fina station, as it provided an inconspicuous place to monitor traffic.

According to a report officer Dave Anderson later wrote, he stopped into the Fina station around 5:10 p.m. on the 4th of July to buy a drink. He chatted briefly with Nancy, and said everything seemed “10-4.” That’s police dispatch code for “roger” or “understood.” In the context of this report, it appears Anderson meant “ok,” as in, he didn’t notice anything out of the ordinary.

The report says officer Dave Anderson then received a radio call about a situation at the other gas station, just on the other side of the highway, kitty-corner from the Fina station. So, at about 5:20 p.m., Dave went to his car, drove across the four lanes of traffic, and confronted two men suspected of driving drunk. He reportedly pulled their licenses and radioed their information to dispatch.

This timeline provided by officer Dave Anderson in an official report put him at the Fina station during the same period of time David and Jana Williams, the two child witnesses, were there with their dad. But the Williamses never mentioned seeing a police officer.

David Williams: I’ve never read the report but what did surprise me when I, I heard is that there was an officer across the street and I don’t recall if they have a timestamp on that.

Dave Cawley: The two timelines conflict with one another. And when the story of Nancy Baird’s disappearance first made the news, it was officer Dave Anderson’s version that was publicly reported. But based on my review of the records, it seems likely officer Anderson left the Fina station before the Williams family arrived, because they did not see a police car there.

Jana Williams Grow: I remember thinking it was a, not very many, it was a quiet time.

David Williams: No, it was, there weren’t many vehicles there.

Dave Cawley: At about 5:30 p.m., while officer Dave Anderson was still across the highway dealing with the suspected drunk drivers, a woman named Bonnie Peck dropped by the Fina station. She was the manager, Nancy Baird’s boss. Bonnie went to the cash register to grab a few bucks, only to find an irritated man waiting there.

“Did you go for a beer or something,” he quipped.

Bonnie shot the man a quizzical look.

“Isn’t she here,” Bonnie asked, referring to Nancy.

Bonnie looked around and realized Nancy was not at the station.

Officer Dave Anderson reported he looked back across the highway at the Fina station at about 5:35 p.m. He saw a green van parked out front, with several “hippie types,” as he described them, milling around. Anderson said he drove back across the highway to the Fina station to “check it out.”

It’s not clear why he believed a van parked outside a gas station amounted to a situation that needed checking out. And officer Anderson’s report doesn’t say anything about these hippie guys and their van after that. Instead, he described stepping inside the convenience store to see a frazzled Bonnie Peck standing at the register.

“Have you seen Nancy,” Peck reportedly asked officer Anderson.

“Yeah,” Anderson said. He’d seen her about 15 or 20 minutes ago, when he’d bought a soda from her. She wasn’t around?

“No,” Bonnie said. But Nancy’s purse and keys were both still inside the Fina station, so it didn’t appear Nancy had left on her own. Officer Anderson peered outside and saw Nancy’s car. Another clue suggesting Nancy had not driven away by herself.

Officer Anderson picked up the telephone and dialed his chief, a man named Ray Adams. It rang with no answer. Anderson wrote in his report he then dialed the phone number of Floyd Dee Baird, Nancy’s ex-husband. Anderson didn’t explain how he knew who Nancy’s ex was, so this could be an indication he knew Nancy as more than just an acquaintance. In any case, Floyd Dee Baird didn’t answer, either.

Anderson keyed his radio, connecting with dispatch in the neighboring city of Layton. He asked an officer there to call the local hospitals, to see if Nancy Baird might’ve had a medical emergency. Then, with no better idea of what to do, officer Anderson stepped outside and started to search the area around station for any sign of Nancy.

The Fina station faced east, toward the highway and the Wasatch Mountains. To the north was Cherry Lane, a quiet street lined with single family homes. To the south…

David Williams: South was just an orchard.

Jana Williams Grow: Just vacant, yeah, it was an orchard.

Dave Cawley: A few small outbuildings sat on the edge of the orchard. Anderson poked around them, as well as a set of storage sheds tucked behind the Fina station. He didn’t report finding anything.

At around 7 p.m., an hour-and-a-half from when Nancy Baird was last seen, Nancy’s older half-sister Norma dropped by the Fina station to talk to Nancy. She instead ran into officer Anderson, who was still searching the grounds. Norma asked where Nancy’d gone. Officer Anderson didn’t have an answer.

Norma took officer Anderson up to her parents’ house. Anderson asked Nancy’s parents if anything had seemed amiss that day. They said no, Nancy’d been in good spirits. And they were still tending her four-year-old son. They didn’t think Nancy would’ve taken off without him.

Dave Anderson was out of his depth. He didn’t have the training or experience to know how to investigate a case like this. So he drove down to his police chief Ray Adams’ house and picked him up.

Ray Adams wasn’t much more of a cop than officer Dave Anderson. But Adams lived around around the corner from a Davis County Sheriff’s deputy named Bud Cox. Adams briefed Cox on the situation and asked what he and officer Dave Anderson ought to do about it. In a report, deputy Cox wrote he thought the situation warranted “serious investigation.”

“What if she doesn’t come back by morning,” chief Ray Adams reportedly asked.

Deputy Cox said in that case, they should perform an all-out search. Assume the worst and hold nothing back.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: Early on Saturday July 5th, 1975, the morning after Nancy Baird vanished, a group of deputies and detectives from the Davis County Sheriff’s Office received a page. One of them was a man named Kenny Payne.

Kenny Payne: All the sudden we got a notice that says that Lieutenant Egbert wants a meeting with these people at 9 o’clock in the morning down at the Sheriff’s Office.

Dave Cawley: Kenny arrived at the sheriff’s office to find a group of about 10 of his colleagues there. East Layton’s police chief Ray Adams and the town’s lone full-time officer, Dave Anderson, were there, too.

Dave Cawley (to Kenny Payne): What was your opinion at the time of the East Layton Police Department?

Kenny Payne: Well, umm, inexperienced would be one.

Dave Cawley: Many of the Davis County deputies did not hold their colleagues from East Layton in high regard, for reasons we’ll explore in more detail a bit later. It’s enough to know for now East Layton lacked the manpower and know-how to run a major missing persons investigation. And that’s why the Davis County Sheriff’s Office stepped in to help.

Officer Dave Anderson briefed the deputies about the circumstances of Nancy’s disappearance. He told them she’d left her car keys and purse behind, with 167 dollars in cash still in her wallet. That struck Kenny as odd.

Kenny Payne: Then her just disappearing, you say “well ok that’s,” y’know, “something’s happened.”

Dave Cawley: Officer Anderson said the night prior, he’d gone to Nancy’s house and retrieved an address book containing names and numbers of Nancy’s friends. He’d also obtained a photo album, which included pictures of Nancy and some of the men she’d dated since divorcing her ex-husband, Floyd Dee Baird.

Sheriff’s lieutenant Dean Egbert handed out assignments. One of the deputies would go up in a helicopter to visually scan for any sign of Nancy along the highway. Others would make contact with Nancy’s friends and romantic partners, past and present.

Two names had risen to the top of that list: Floyd Dee Baird, Nancy’s ex-husband, and Dennis Forsgren, a recent divorcé Nancy’d spent time with. Deputies soon learned both men had alibis. Floyd Baird had gone to Jackson Hole, Wyoming with a friend for the 4th of July holiday weekend. Dennis Forsgren was traveling as well, with his parents in Phoenix, Arizona. They’d both left the state at least a day before Nancy vanished.

Floyd Dee Baird and Dennis Forsgren are both deceased, so I can’t talk to them. But it’s clear from the case records they didn’t remain persons of interest very long. Their alibis were quickly verified.

The sheriff’s deputies did hone in on a third man though, whose alibi wasn’t quite as solid. His name was Monty Torres. So now, I’m going to tell you how deputies identified Torres as a person of interest.

Sheriff’s detective Kenny Payne received an assignment as well on that Saturday morning.

Kenny Payne: My assignment was to go up to Park City where Mr. Williams and his family were playing golf.

Dave Cawley: Earlier, we heard from the Williamses, David and Jana.

Kenny Payne: Apparently they were the last persons to see anybody in the store.

Dave Cawley: But how did investigators know this? The credit card receipts. East Layton police had retrieved receipts from the Fina station. They found the imprint of Denzle Williams’ card that Nancy’d made, using that imprinter device, mere minutes before she vanished. They’d called Denzle, only to learn he and his son David were not at home.

Kenny Payne: I asked the lieutenant, I said “ok, now what are they doing?” “They’re playing golf.”

(Sound of a golf swing)

Dave Cawley: Young David Williams was on the golf course with his dad when someone approached.

David Williams: The assistant or person up there came out and said “there is a detective who would like to talk to you about about, uh, a missing persons.” And we’re like “who?” And they indicated that it was this, this girl from the Fina gas station and we were the last people to see her.

Dave Cawley: Detective Kenny Payne joined the Williamses.

David Williams: Rode with us in the golf cart and interviewed my father and I. He would just talk to us after every shot.

Kenny Payne: 18 holes, y’know, and I didn’t want to give any golfing advice, ‘cause I don’t golf.

David Williams: We’d get in and he’d ask questions and that’s kind of what I remember.

Dave Cawley: It all seemed surreal to David Williams.

David Williams: And I was thinking “that’s got to be a mistake. I just saw her. I was just, I saw her, she was fine,” and I couldn’t believe, really, that she was gone.

Dave Cawley: I have a copy of a report Kenny Payne wrote about this interview. It says Denzle Williams described pulling up to the pump and seeing an older man entering the restroom at the Fina station.

David Williams: The restroom was a separate building.

Dave Cawley: The guy came out a couple of minutes later, while the Williams children were still inside paying for the gas and a soda. The restroom guy was tall, skinny, dark-haired and wore cowboy boots. He walked a bit funny, and might’ve been drunk. Denzle wasn’t sure where that older man ended up, but he didn’t recall seeing this cowboy enter the convenience store.

David Williams told Kenny Payne about the two men he’d seen inside the store. Kenny pressed for specifics about their appearances.

Kenny Payne: Y’know, we’d talk about eyes and then they’d get off and go hit the ball and then get back on. We’d talk about more eyes or more ears, hair.

Dave Cawley: David described them. The word “hippie” came up. I can’t believe I have to explain this, but for younger listeners, hippies were part of a counter-culture movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Think tie-dye, psychedelic rock, free love and anti-war sentiment.

The two men seen talking to Nancy Baird might not have been actual hippies. But they were bearded, with long hair and wore a lot of denim.

David Williams: Yeah, what they would say a hippie vibe that they—

Dave Cawley (to David Williams): Not uncommon.

David Williams: —right.

Jana Williams Grow: Right, right.

David Williams: Not uncommon in the ‘70s, right?

Dave Cawley: Kenny Payne learned Jana Williams had likely seen these two men as well. He asked Denzle if he could meet with the kids later that evening, so they could put together composite sketches of the men, to assist in identifying them. Denzle agreed.

Jana Williams Grow: I just remember he and my mom coming to me and saying “we have to go because you were the last one to see her.” Which really stuck in my mind, ‘cause that was a scary thing. I, I didn’t know how someone could take a pretty lady like that and she’d just gone missing.

Dave Cawley: Jana sat with her brother, parents and sheriff’s detective Kenny Payne on that Saturday night. Kenny brought a wood box with him. I brought a similar box when I went to interview Kenny.

Dave Cawley (to Kenny Payne): So Kenny, tell me what we’re looking at here.

Kenny Payne: This is an Identi-kit.

Dave Cawley: Identi-kits were invented in the 1960s. Police agencies could use them to create composite images of suspects, without needing to hire a sketch artist. Each Identi-kit composite started with an interview.

Kenny Payne: Did he have any particular facial features that really stood out?

Dave Cawley: Kenny posed this question to young Jana Williams.

Jana Williams Grow: I remember explaining his eyes. So I must have looked at his eyes and his eyebrows.

Dave Cawley: Each Identi-kit came with a booklet that served as an index for each part of the face. Kenny handed the booklet to Jana, while asking another question.

Kenny Payne: Can you look through some of these and find some eyes that look like what you remember? What they’d do is they’d say well “hey yeah, I really like this one.”

Dave Cawley: Each image in the booklet was coded by letter and number. E for eyes, L for lips, H for hair and so on. The investigator would take note of those codes, then dig into that wood box I mentioned a moment ago. It held a few hundred sheets of transparent plastic. Kenny calls them “foils.”

Kenny Payne: The foil is numbered down here at the bottom, if you look right here. See this is 01. Y’know, eyes.

Dave Cawley: By stacking and aligning the transparent foils, an investigator could build a two-dimensional face, feature-by-feature.

Kenny Payne: When you get all of this done, then you’ll be able to read a code across the bottom of it which is just a composite of all the, all the numbers that come across there and I umm, obviously wrote down the codes in my report.

Dave Cawley (to Kenny Payne): Mmhmm.

Kenny Payne: And I commend you for, y’know, tracing down an Identi-kit ‘cause that’s almost an impossibility anymore.

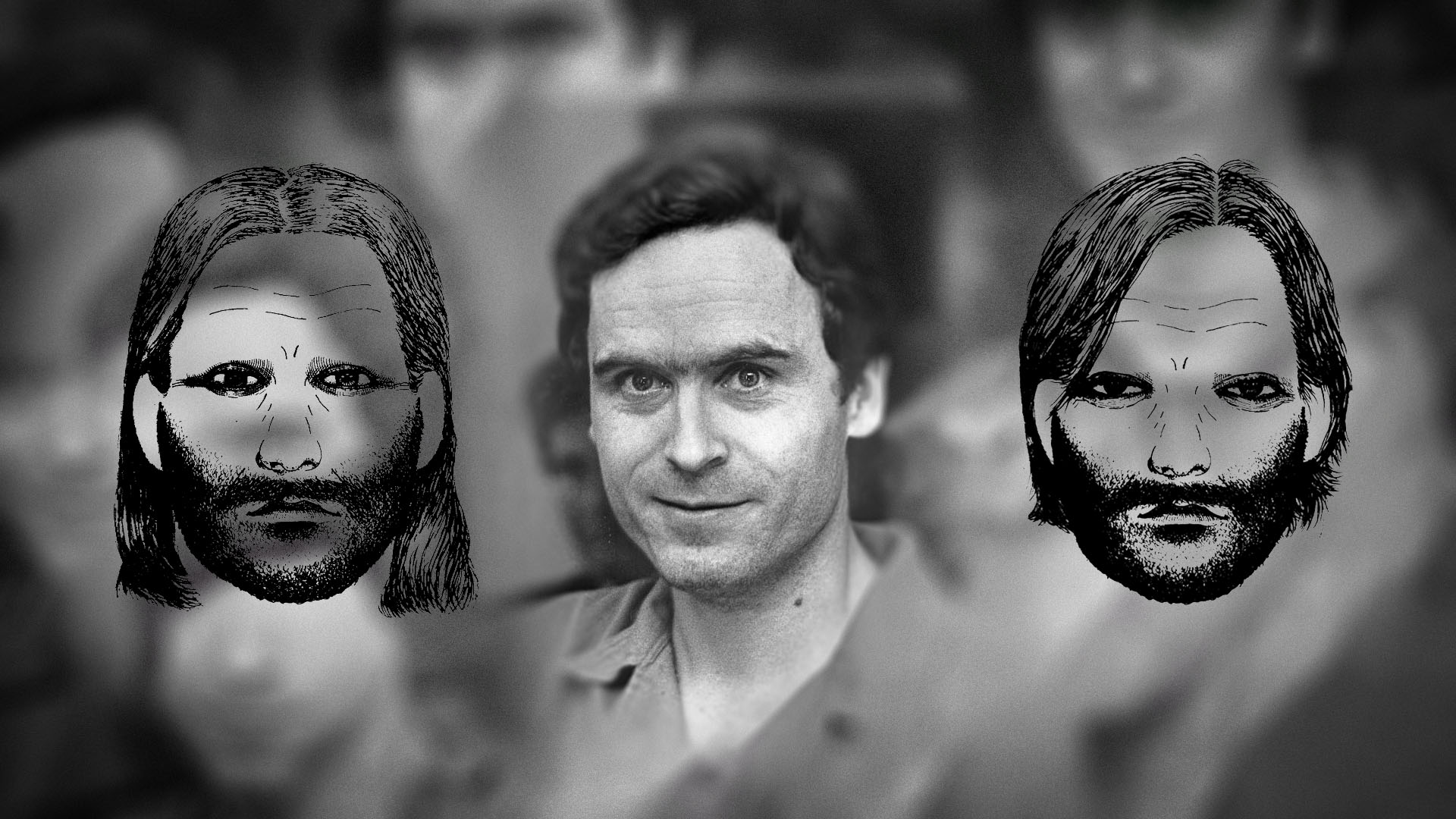

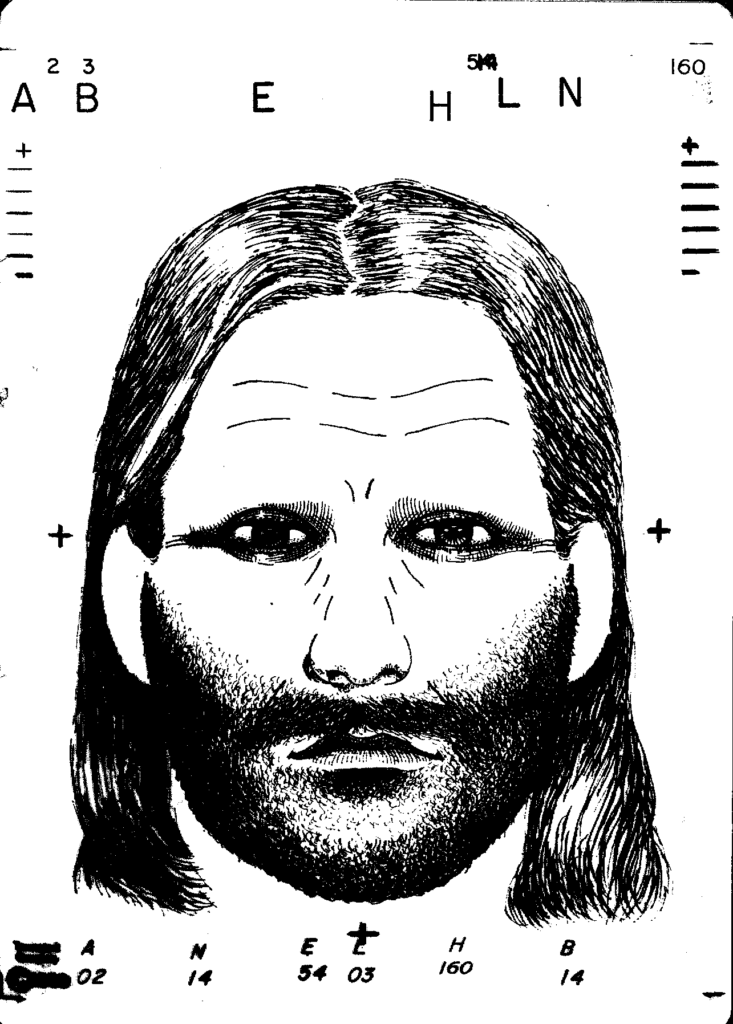

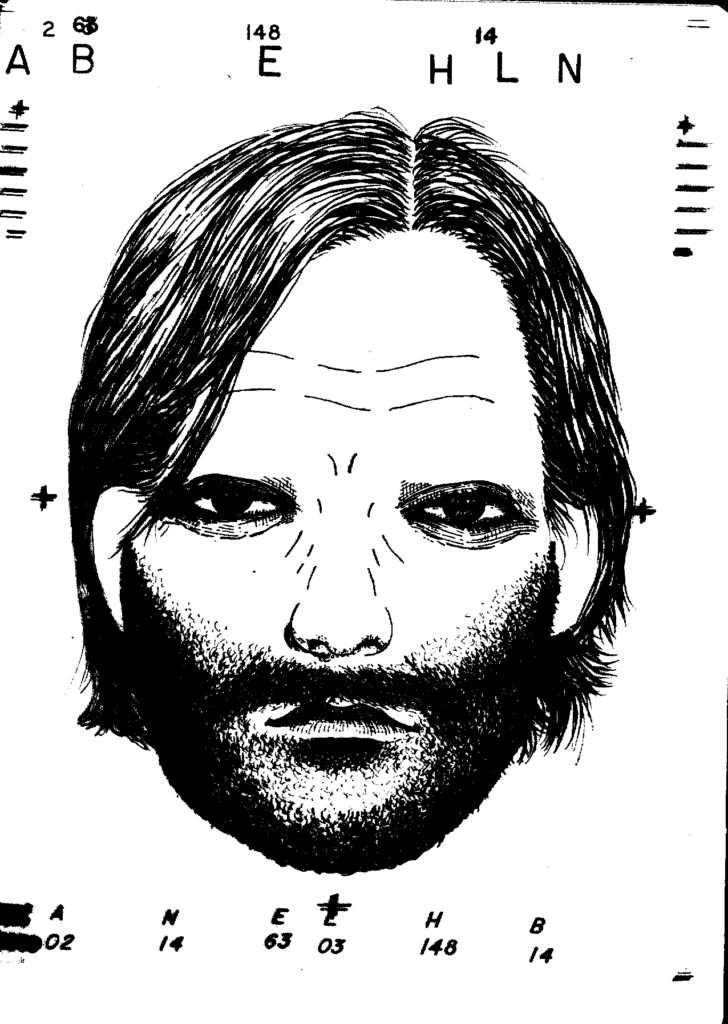

Dave Cawley: I failed to mention, when I first obtained the Nancy Baird case files, they included Kenny Payne’s report about building three Identi-kit composites based on the descriptions provided by the Williams family. His report had the codes, but not the images.

I soon learned I could recreate the images using those codes, if I could find an old Identi-kit. But that’s not easy, because they’re antiques and most were long ago destroyed. I spent months waiting for one to pop up on eBay. I can now tell you what those three composites Kenny Payne built back in 1975 looked like. There’s an old, craggy-faced fellow. He was the cowboy in the parking lot outside the Fina station.

Kenny Payne: But the ones who were talking, actually talking to Nancy were these two.

Dave Cawley: The composites of the other two “hippie type” men look very much alike. They used the same nose, lips, beard and age lines. Only their hair and eyes set them apart.

Kenny Payne: Y’know, I told the lieutenant, I said “they, they could very well be brothers.”

Dave Cawley: Davis County deputies compared the composites to the pictures in Nancy Baird’s photo albums. They noticed one of the two “hippie type” composites looked an awful lot like a man in one of Nancy Baird’s pictures. And that photo was marked with a name: Monty Torres.

I’ll stress here, Identi-kit composites were far from exact. They might get an investigator in the general neighborhood, but were far from photorealistic.

Kenny Payne: I wish they would’ve had better technology back in the, in the days. But they, we had what was best at the time.

Dave Cawley: I’m publishing these three Identi-kit composites from the Nancy Baird case at thecoldpodcast.com, so you can see them and judge for yourself.

Case files say deputies showed the photo of this man, Monty Torres, to their witness, Jana Williams. Jana “positively identified the picture of Monty Torres as one of the hippie type individuals.” Clearly, the Davis County detectives needed to talk to Monty Torres. They quickly learned Torres was at that time staying in Pocatello, Idaho, about two-and-a-half hours away. The deputies reached out to a detective in Bannock County, Idaho and asked him to find Torres and interview him. The detective did, and according to a report, the Idaho detective described Torres as acting “quite jittery.”

Monty Torres reportedly told the Idaho detective he had an alibi for the evening of July 4th. He said he’d been vacationing at Lava Hot Springs, a resort and waterpark just outside of Pocatello. Torres gave the detective a name of someone who could supposedly confirm his story. But by the time deputies in Utah brought that man in for questioning, they learned Torres had already called him and coached him on what to say.

Here’s what Davis County sheriff’s lieutenant Dean Egbert told the Deseret News about it, his words read by a voice actor.

Aaron Mason (as Dean Egbert from July 10, 1975 Deseret News article): We are not satisfied with this deal in Idaho, and we are considering asking the man to undergo a polygraph test next week.

Dave Cawley: That’s exactly what happened. Deputies hauled Monty Torres in for a polygraph examination about two weeks following Nancy Baird’s disappearance. I’ve searched for records that would reveal the specific questions asked, as well as Torres’ responses, but I’ve so far been unable to find them.

All I can tell you comes from old news reports, that say all of the persons of interest in Nancy Baird’s disappearance had alibis or passed polygraph examinations. In other words, investigators believed Monty Torres excluded himself as a suspect by passing a polygraph. It surprised me to see how much weight the investigators placed on this single polygraph exam. Polygraphs are not fool-proof.

Kenny Payne: Your biggest thing is if I get to interview you face-to-face and umm, y’know when I start talking to you, I’m usually talking to you when I’ve got a loaded question and I, I know what the answer is. I’s just going to see what your answer is.

Dave Cawley: I can’t judge how convincing Monty Torres’ responses were during the polygraph, because I don’t even know what investigators asked him. But Kenny did tell me he recalled some division among investigators afterward.

Kenny Payne: Some people they ruled him right out and other people said “no I, I don’t think so.” And so I, y’know I, I haven’t given up on that one either.” (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: The story of these two “hippie type” guys seen talking to Nancy Baird just before she disappeared matters more than you might realize. What I’m about to say has never been publicly revealed. It’s been secret of the Nancy Baird case file for nearly 50 years.

Nancy had a friend named Deloris Drake, who lived in the city of Ogden. A Davis County sheriff’s deputy interviewed Deloris early in the investigation. Deloris said on the night of July 2nd , less than 48 hours before Nancy Baird disappeared, she, Nancy and a friend of theirs named Peggy went out on the town. Davis County sheriff’s lieutenant Dean Egbert summarized Deloris’ account in a report. Here’s what he wrote:

Aaron Mason (as Dean Egbert from July 14, 1975 police report): Deloris mentioned Rigos and the Iron Horse.

Dave Cawley: Those were two bars in Ogden, where Nancy, Deloris and Peggy stopped that night. Peggy headed home around 10:30 p.m., but then Nancy and Deloris went back out…

Aaron Mason (as Dean Egbert from July 14, 1975 police report): …and had driven in the area of Washington Boulevard until approximately 2:30 and Nancy had taken Deloris home. At approximately 0300 on the morning of the 3rd, Nancy had returned to Deloris’ apartment and appeared to be quite shaken and frightened … that this fellow named “Tom” in a yellow van had followed her home and was molesting her.

Dave Cawley: The report doesn’t say if the word “molesting” was a direct quote from Deloris, or the lieutenant’s interpretation. In this context, the word carries some ambiguity. “Molest” means to pester or harass, but it can also mean to physically sexually assault. It’s not clear which meaning lieutenant Egbert intended. In any case, he continued:

Aaron Mason (as Dean Egbert from July 14, 1975 police report): Deloris reported that Tom had said that “you’re going to [expletive] or else” as she opened the door. Deloris ordered this Tom from the premises and during the commotion, Deloris’ father, who lives across the street, had come from his home and that this time Tom had left in the yellow van.

Dave Cawley: This fellow “Tom” wasn’t alone.

Aaron Mason (as Dean Egbert from July 14, 1975 police report): There was also another individual who was riding a motorcycle.

Dave Cawley: Two men, one driving a Volkswagen van. Remember, East Layton police officer Dave Anderson reported seeing a van parked outside the Fina station moments before discovering Nancy Baird had disappeared. Earlier, you heard from David and Jana Williams, who as children were the last people known to have seen Nancy Baird alive. David told me he remembered reading the newspaper reports recounting officer Anderson’s version of events.

David Williams: The officer looks over and sees that there’s people that are trying to buy gas or trying to pay for snacks.

Dave Cawley: When I interviewed David and his sister Jana, I pressed them, asking if they remembered seeing any other cars outside the Fina station.

Jana Williams Grow: I don’t remember a lot of vehicles there.

Dave Cawley: David appeared lost in thought for a moment, as if seeking back through the fog of distant memory.

David Williams: I think there, there may have, like, a van, brown in color. Umm, that kind of looked like a hippie van which is, kind of, that was parked on the, uh, north side.

Dave Cawley: My ears perked up when David said this. He hadn’t mentioned a van when interviewed by detective Kenny Payne on the golf course back in 1975. And I’d scoured the archives of several Utah newspapers from the time. The articles published back then did not include officer Anderson’s detail about seeing a van. That tidbit was a guarded piece of the investigation, not publicly revealed. So I don’t think it’s possible for David Williams’ memory to have been tainted by news reports.

This is significant, for two reasons. First, it bolsters East Layton police officer Dave Anderson’s story of having seen a van from across the highway. But more significantly, this van at the Fina station could be the same one a man used to chase Nancy Baird to the doorstep of her friend Deloris’ house, less than 48 hours before Nancy disappeared.

Deloris told a deputy she recognized this man, “Tom.” She gave investigators his last name, Stone, and said he lived nearby. A solid lead and yet, the investigators appear to have done nothing with it.

There’s no indication in the Nancy Baird case files I’ve obtained East Layton police ever followed up on this lead Davis County uncovered about Nancy being stalked and potentially sexually assaulted two nights before she disappeared. In fact, on July 28th, 1975, East Layton police chief Ray Adams told the Deseret News his department was “at a dead-end” in the search for Nancy Baird. The chief said they’d exhausted their leads and would have to brainstorm a new “route to travel” in the investigation.

That’s absurd. Less than a month had passed since Nancy’s disappearance and already East Layton police were ready to throw in the towel? What the public didn’t yet know was the tiny department with a staff of just four—a part-time chief, a full-time officer and two part-time reserve officers—was on the brink of meltdown.

Chief Adams needed an alternative explanation, other than his own department’s incompetence, to explain what’d happened to Nancy Baird. Only a couple of weeks later, a trooper 30 miles south on the outskirts of Salt Lake City would arrest a young law school student named Theodore Bundy.

John Hollenhorst (from July 24, 1979 KSL TV archive): For a long time, residents of Utah, Colorado and Washington have been following an incredible mystery story: a story of murder, imprisonment and escape. And all along there has been one fascinating question: could a handsome, articulate, intelligent law student—with a promising career in politics—could Theodore Bundy be a crazed sex killer, responsible for the brutal murders of perhaps dozens of young women all across the West?

Dave Cawley: Serial killer Ted Bundy’s downfall began in the state of Utah. In November of 1974, Bundy tried to abduct a woman named Carol DaRonch from a shopping mall in the suburbs of Salt Lake City. Carol fought back and managed to escape, still carrying the handcuffs Bundy tried to place on her.

Richard Bingham (from February 5, 1986 KSL TV archive): Bundy is also a suspect in the disappearance of Debi Kent from Viewmont High in Bountiful.

Dave Cawley: On the same evening as his failed attempt to abduct Carol DaRonch, Bundy drove north to the city of Bountiful, Utah. He kidnapped a teenage girl named Debra Kent, plucking her from the parking lot outside Viewmont High School. Police found a handcuff key on the asphalt there. It matched the cuffs from the Carol DaRonch case. But no one could find Debra Kent.

Ted Bundy wasn’t arrested until many months later, in August of 1975. He stood trial for the attempted kidnapping of Carol DaRonch in early 1976. Bundy wasn’t charged with the murder of Debra Kent because police hadn’t been able to find her body. I attended the same high school as Debra Kent, though many years later. I remember hearing whispered conversations among classmates even then, in the late ‘90s, full of rumor and exaggeration about Ted Bundy.

Tiffany Jean: And it’s become such a big story, that there’s even become kind of a mythology built up about the case.

Dave Cawley: That’s the voice of Tiffany Jean. She’s a government archivist, based in Texas. In 2019, Tiffany watched a Netflix documentary called “The Bundy Tapes.”

Tiffany Jean: And I’d heard the name before. I think everyone’s heard that name before. I didn’t really know much about the case.

Dave Cawley: Tiffany found herself fascinated, particularly by cases like Nancy Baird’s, where Ted Bundy was suspected but never proven as the killer.

Tiffany Jean: Because he confessed to at least 30 murders, but only 21 have been identified. And that’s always been a special interest of mine is seeing if I could shed any light on who those other women could be.

Dave Cawley: Earlier, you heard clips from an interview Ted Bundy gave days before his execution. He admitted in that recording to killing Debra Kent.

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Was she in any way dismembered? Was she buried whole, or?

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Yeah. I mean, yes. You should find all of it.

Tiffany Jean: As far anyone can tell, all of his final confessions right before he was executed were truthful. And that’s because he had some self-interest. He was trying to keep himself alive by giving investigators true information to buy himself some more time. It was his bones-for-time strategy, is what it was called.

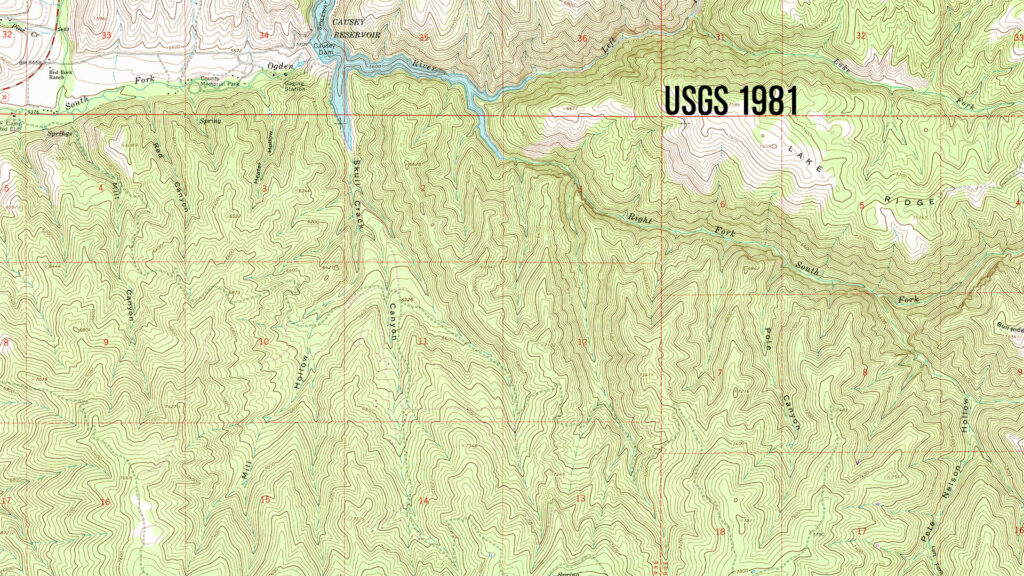

Dave Cawley: Bundy hoped police would search where he indicated, find Debra Kent’s remains, then pressure Florida into delaying his execution so they could look for other victims.

Tiffany Jean: He gave a pretty detailed description of where he buried her.

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Did you go back down through Salt Lake again?

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Oh yes, yes, yes, yes.

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Oh did you?

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Yes.

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): And you went farther south?

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Yup.

Dennis Couch (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Past Provo?

Ted Bundy (from January 22, 1989 police interview recording): Yup.

Dave Cawley: Florida never had any intention of delaying Bundy’s execution. Bones-for-time was a bust for Ted Bundy. Police did later search in the area he’d indicated.

Searcher (from May 6, 1989 KSL TV archive): Ok, let’s go.

Joel Munson (from May 6, 1989 KSL TV archive): Serial killer Ted Bundy said he buried the Bountiful youth somewhere in this area nearly 15 years ago. So with shovels in hand and metal detectors humming away, search and rescue crews went back to work. This is the sixth time they’ve combed the area.

Dave Cawley: It took several tries, but in the end they found a single human bone: a patella, or kneecap.

Allison Barlow (from July 29, 1989 KSL TV archive): They did find some unidentified human remains at the site where Bundy claimed he buried Debra Kent.

Dave Cawley: Years later, DNA analysis would confirm that patella belonged to Debra Kent. Ted Bundy had told the truth in his final days. And, as we’ve already heard, Bundy denied any knowledge of Nancy Baird during that interview.

Tiffany Jean: So when he denies Nancy Baird, that makes me think maybe he was actually telling the truth in this situation.

Dave Cawley: Over the last few years, Tiffany Jean has filed public records requests for case files in the states where Ted Bundy is known and suspected to’ve murdered women.

Tiffany Jean: And some of those turned into a fight. (Laughs) And I just, it was more on the principle than anything else, that they weren’t going to turn over these records that I really felt like they should.

Dave Cawley: In Utah, Tiffany repeatedly won the release of records, many of which had never before been shared publicly. She feels strongly, and I agree, it’s important these records be preserved and studied, with an emphasis on the unsolved cases. Records are a matter of putting facts ahead of mythology.

Tiffany Jean: I want to know what the real story of what happened. And when you’re reading only secondary sources, you don’t really get the whole picture. And that’s what I wanted to do. I wanted the whole picture.

Dave Cawley: Tiffany’s developed a repository of well-sourced, factual information about the crimes of Ted Bundy. She’s published portions of that on her website hiimted.blog.

Tiffany Jean: I just want the most complete archive of the case that exists, just kind of a, that’s kind of my goal at this point.

Dave Cawley: I reached out to Tiffany in 2022. I knew she’d requested the Nancy Baird case file from the Davis County Sheriff’s Office, and been refused, because it’s technically still an open case. I’d also requested the Baird case file and likewise been refused.

Tiffany Jean: I didn’t write a GRAMA appeal like you did, though.

Dave Cawley: GRAMA is Utah’s open records law. After my initial denial, I appealed by arguing Nancy Baird’s case was open, but not active. The public interest for transparency weighed in favor of releasing the records. That argument proved persuasive, and I became the first person outside of law enforcement to review the Nancy Baird case file in nearly 50 years.

Tiffany Jean: So you beat me. (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: I shared what I’d obtained of the Nancy Baird case file with Tiffany. We both knew the public consensus has long been Ted Bundy was somehow responsible.

Tiffany Jean: Which is interesting, because in that case file that you shared with me, his name doesn’t appear at all.

Dave Cawley: This is true. But it’s worth noting all of the files in the records I obtained are dated July of 1975, weeks before Bundy’s first arrest.

Tiffany Jean: And that’s another thing that jumped out at me was how they really didn’t do enough work on this case, or maybe the record’s incomplete. But it doesn’t seem like they followed all the leads that were there at the time.

Dave Cawley: Former Davis County Sheriff’s detective Kenny Payne collected evidence from Nancy Baird’s apartment in the days following her disappearance.

Kenny Payne: Y’know, I remember going down to her house and umm, things that I was really interested in was trying to find something that would be identifiable to, to her.

Dave Cawley: Where East Layton police were tossing up their hands in defeat, Davis County detectives like Kenny Payne were thinking ahead to some day in the future when they might come across Nancy Baird’s remains.

Kenny Payne: And so what I wound up recovering was, uh, two hair brushes.

Dave Cawley: With strands of Nancy’s strawberry blond hair still tangled in the bristles.

Kenny Payne: They’re still in evidence down at the sheriff’s office.

Dave Cawley: Several weeks later, after Ted Bundy’s arrest, police in neighboring Salt Lake County worked with the FBI to scour Bundy’s car. The items they gathered also ended up in evidence boxes.

Con Psarras (from January 24, 1989 KSL TV archive): In the boxes, clues to two killings and a glimpse of a bigger picture: hundreds of hair samples vacuumed from the interior of Bundy’s little green Volkswagen. The hair of at least 100 different people. How many of them victims?

Dave Cawley: Davis County sent Nancy Baird’s hair to the FBI for comparison to the hairs collected from Bundy’s Volkswagen Beetle. The lab did not come up with a match. None of the hairs from the car belonged to Nancy Baird.

Tiffany Jean: So that kind of made me think maybe it wasn’t Bundy maybe it was someone that she knew she was willing to go with.

Dave Cawley: Who might Nancy have trusted? Perhaps a familiar young man dressed in a police uniform.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: One of the people I’ve most wanted to talk to about the Nancy Baird case is former East Layton police officer Dave Anderson, the man who first reported Nancy missing.

Dave Anderson is one of the only people who could’ve successfully lured Nancy Baird out of the Fina station during the narrow window of five or ten minutes between when she was last seen by David and Jana Williams and when her manager showed up and discovered she was gone. The chief should’ve sidelined officer Anderson until he could be cleared as a person of interest. But that didn’t happen. And I can’t confront former officer Dave Anderson about this, because he’s dead. Regardless, let’s explore officer Anderson’s background so you can see why I view him in such a critical light.

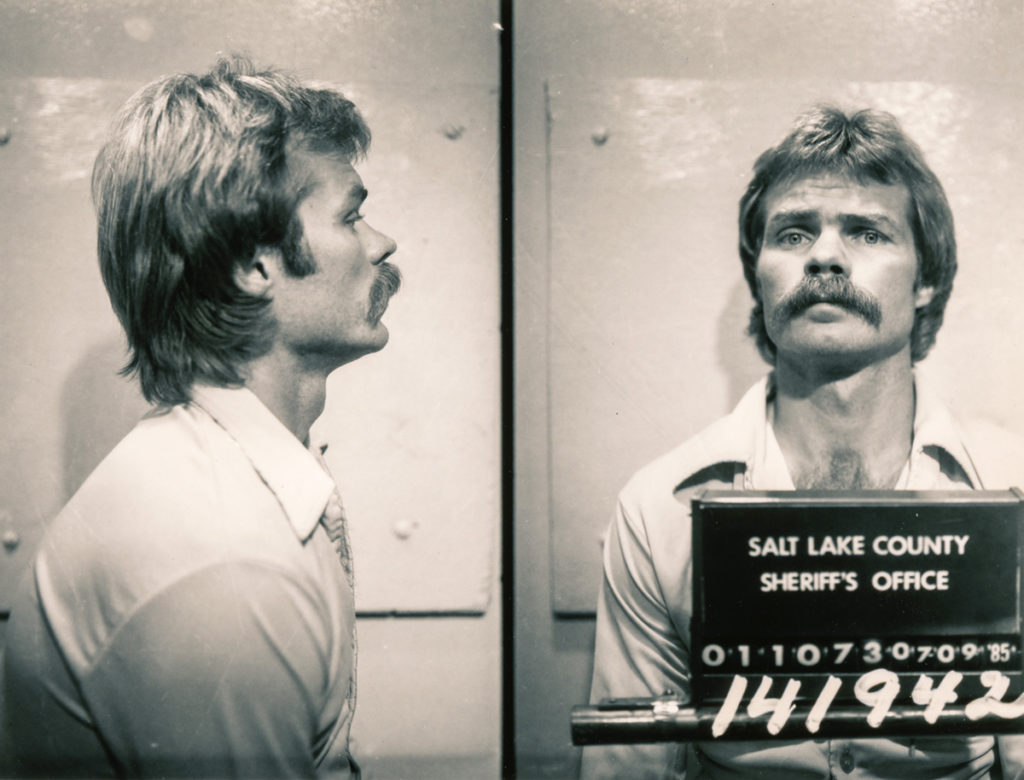

David Ray Anderson was born in May of 1951, the third of three children in his family. He never knew his older sister, because she died after being accidentally backed over by her father. But Dave Anderson did grow up with a brother, Earl, who was two years his senior.

When Dave was 8, his father moved their family to the city of Layton, Utah. Dave attended Davis High School, graduating in the class of 1969. That’s a different school and one year ahead of Nancy Baird, so I’m not sure if they would’ve crossed paths at that point.

A year later, in April of 1970, Dave married a woman he’d gone to high school with named Marilyn. He attended basic training for the United States Marine Corps that summer and in the fall, he and Marilyn welcomed their first child.

Dave’s parents moved away from Layton a short time later. They bought an old farm house 100 miles away, in the rural town of Nephi, Utah. Dave followed them, dragging his reluctant bride and their baby out to the countryside. The Andersons had a second child while living in Nephi. But all was not well behind the scenes. Dave Anderson’s marriage was on the rocks. His wife hated living in the sticks. And his older brother was about to throw the whole family into turmoil.

In June of 1972, Dave’s older brother Earl and a few other guys burglarized a business. Earl and his companions stole cash, credit cards, liquor and a handgun. Earl landed in the Utah State Prison on a felony conviction. Newspaper archives show while in prison in August of 1973, Earl set another inmate on fire, leaving that man with serious burns over most of his body. Prosecutors charged Earl with attempted homicide, and moved him out of the state prison to a county jail, for his own protection. It wasn’t enough. Retribution came in January of 1974, when a group of jail inmates jumped Earl. They allegedly forced Earl to swallow tranquilizer pills, then smothered him until he was dead.

Dave Anderson was just 22 when he buried his brother. I don’t know exactly how this experience impacted him, but it’s notable Dave immediately turned his career aspirations toward becoming a cop. And this was just a year-and-a-half before Nancy Baird disappeared.

Dave’s wife, meanwhile, had reached her breaking point. She separated from Dave and moved back home to Layton. A short time later, she filed for divorce. Dave followed his estranged wife and kids to Layton, finding a place of his own nearby. He enrolled in a criminal justice program at Weber State College and, in October of 1974, landed a job as a police officer for the town of East Layton. That was just 10 months before Nancy Baird disappeared.

As I said before, the majority of Dave’s hours were spent patrolling U.S. Highway 89. And he spent a lot of that time parked at the Fina station where Nancy worked. Anderson was a young, inexperienced cop with a complicated home life when he spoke to Nancy at the Fina station minutes prior to her disappearance. We have only his word that their conversation was polite.

It’s jump to go from there to seeing officer Dave Anderson as a suspect. But what piques my interest is what happened next: Anderson abandoned his budding law enforcement career just a couple of months after Nancy Baird disappeared. I’m not sure why.

Requirements to become a certified police officer in Utah during the 1970s were a lot more lax than they are now. Under the law at the time, a prospective officer was supposed to complete 200 hours of training at the academy within 18 months of being hired by a police agency. So when East Layton hired Dave Anderson as its only full-time police officer in 1974, it started a countdown clock ticking. He had a year-and-a-half to get certified, or he was out of a job.

Landing a spot at the police academy wasn’t easy. Prospective officers needed to be sponsored. So guys like Dave Anderson would often get hired by a small town, attend the academy on the town’s behalf, then quit the small town job to take a better-paying position at a bigger city department. Anderson’d probably hoped East Layton would sponsor him to the academy. But that never happened. I can’t find any record of him getting a police job anywhere else. He just walked away.

Anderson becomes very difficult to track after that point. Court records show his ex-wife, Marilyn, filed a lawsuit against him in 1989, seeking thousands of dollars in unpaid child support. Dave’s name appears in both of his parents’ obituaries during the early ‘90s. Then, he’s a ghost. I know he ended up just over the state line in Mesquite, Nevada during the early 2000s. But there, records show “officer” David Ray Anderson died in August of 2010. There’s no record to suggest he was ever challenged on the story he’d told about the disappearance of Nancy Baird.

Dave Cawley: It’s a windy day in the spring of 2023. I’ve spent the last few hours in the car with my boss and collaborator, Sheryl Worsley, headed to a remote community along the Snake River.

Dave Cawley (to Sheryl Worsley): Sheryl, for the record why don’t you state where we are and what we’re doing.

Sheryl Worsley: Well, we are, I’m not sure where we are, Dave. (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: Buhl, Idaho.

Sheryl Worsley: We are in Buhl, Idaho.

Dave Cawley: We’ve come, unannounced, in the hopes of talking to one of the other men who worked for the East Layton Police Department in 1975.

(Sound of seat belt click)

Sheryl Worsley: We’ll see. (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: See what kind of reception we get.

Dave Cawley: His name is Thomas Jackson, Junior. As we walk toward his door, a tall white-haired man steps out.

Dave Cawley (to Tom Jackson): Hi, how you doing? Are you Tom?

Dave Cawley: Tom Jackson can see the microphone in my hand. He asks “uh oh, what did I do now” with a bit of a laugh.

Dave Cawley (to Tom Jackson): You did nothing.

Sheryl Worsley: You didn’t do anything. (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: We’re doing a history project on the Nancy Baird case. From way back in—

Tom Jackson: Oh, Nancy Perry Baird?

Dave Cawley: You got it.

Tom Jackson: When I was a cop? Yeah.

Dave Cawley: Yeah.

Sheryl Worsley: Yeah.

Tom Jackson: Oh, that’d be great. Uh, you want to come in?

Dave Cawley: Is that ok?

Sheryl Worsley: Is that alright?

Dave Cawley: He ushers us inside and makes space on the couch.

Tom Jackson: I’m glad you’re here. Man, this is, just been exciting to know that her case is still open and is, I’m tickled.

Dave Cawley: Tom Jackson was about four years older than Nancy Baird. And he confirms, they knew each other as kids.

Tom Jackson: She was a pretty gal.

Dave Cawley: Tom’d lived just down the street from Nancy. In fact, he’d even married one of Nancy’s friends, a neighbor girl. They’d stayed in the neighborhood, living just off Cherry Lane, a little ways behind the Fina station where Nancy’d worked.

Tom worked a full-time job, but around the start of 1975 also accepted a part-time position as a reserve officer for the East Layton police department. His reserve role was a little different than Cary Hartmann’s, which we heard about in Cold season 3. East Layton was a lot smaller than Ogden City, so it asked much more of its reserves. As a result, Tom worked a more regular schedule, received a paycheck, and wrote a lot of tickets.

Tom told me on the day Nancy Baird disappeared, he’d been driving around in one of the town’s two police cars.

Tom Jackson: I didn’t even hear anything on the radio about it.

Dave Cawley: Which is a little strange, since officer Dave Anderson did describe radioing dispatch about Nancy in his report. In any case, Tom said he’d stopped by the Fina station that evening and found his chief, Ray Adams, and officer Dave Anderson there.

Tom Jackson: I pulled in, I was like “what’s going on?” And they said “Nancy’s gone.” I said “what the crap, what?”

Dave Cawley: Tom remembered going to Nancy’s house and helping retrieve her address book. According to a report, Tom and the chief then went and looked around a place called Fernwood Park, as the dark of night descended. Why Fernwood? Well, it was home to a sort of “lover’s lane,” a place in the hills where couples would park their cars and make out. The police found no sign of Nancy there.

Records show Tom Jackson didn’t have any involvement with the Nancy Baird case after that. He intentionally opted out.

Tom Jackson: At that time, I don’t think I was, I don’t know, I wasn’t a good cop, I would say. I wanted to, I wanted to let someone else handle it. I didn’t want to mess it up.

Dave Cawley: In spite of this, East Layton sent Tom Jackson to the Utah police academy in September of 1975. That’s only about two-and-a-half months after Nancy Baird disappeared. Why did Tom go to the academy, instead of officer Dave Anderson? I’m not sure. Tom didn’t remember.

I’ve talked to one of Tom’s academy classmates. He said Tom struggled a bit, but Tom did graduate the academy and was certified to work in law enforcement. He replaced Dave Anderson as East Layton’s full-time police officer. At some point in the middle of all this, Tom talked to the Davis County Sheriff’s Office about next-steps in the Nancy Baird investigation. East Layton had jurisdiction. It was their call.

Tom Jackson: The county asked me, says “you want to handle this?” And I says “no way! All we are is just little hick town cops here so if we’re gonna find her, you guys is the ones that’s gotta do it.”

Dave Cawley: Tom knew the county had already tracked down several of Nancy’s boyfriends, working off her address book.

Tom Jackson: They had the book and whatever name was in there, they went after ‘em.

Dave Cawley: But the boyfriend leads ran dry, right around the time Ted Bundy entered the picture.

Tom Jackson: Yeah, there was suspicion of him.

Dave Cawley: Tom’s mind didn’t settle on Bundy, though. He figured Nancy’s abductor could’ve been much closer.

Tom Jackson: This person must’ve been someone she knew and had some trust in him. That’s the other reason why I thought it was one of the cops, that one cop.

Dave Cawley: Former officer Dave Anderson. Tom remembered Dave Anderson spending a lot of time at the Fina station.

Tom Jackson: He spent too much time looking at women, too.

Dave Cawley (to Tom Jackson): Thinks he’s a lady’s man, maybe—

Tom Jackson: Yeah.

Dave Cawley: —a little bit?

Tom Jackson: He was a good-looking guy, so I’m sure he thought so.

Dave Cawley: This description of former officer Dave Anderson reminded me of Cary Hartmann and his brief time in the Ogden police reserve corps, which we talked about during Cold season 3. There are some people who are drawn to law enforcement jobs for all the wrong reasons. Dave Anderson, it seems, might’ve been one of them. This idea was overlooked though, probably because the East Layton police department was itself in crisis. Its chief, Ray Adams, shouldn’t have been chief. He’d wasn’t a cop. He’d secured his position through the good ol’ boy system. State law required he attend the academy, but he wasn’t willing to take a leave from his full-time job to do that.

So, in April of 1976, Ray Adams vacated the chief of police position. He instead became a justice of the peace for the town, a form of low-level judge, a job for which Adams was also not qualified. Officer Tom Jackson departed the East Layton police department not long after that. He decided to leave law enforcement entirely, and went into private security work. So within about a year of the disappearance of Nancy Baird, the entire East Layton police force turned over.

Tom Jackson: Real Mayberry thing. (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: There is one other point I need to acknowledge here: former officer Tom Jackson has a criminal record. In 1986, 11 years after the disappearance of Nancy Baird, Davis County prosecutors filed a criminal charge against Tom. He stood accused of sexually abusing two young girls. He pleaded guilty to a second-degree felony, which made him eligible for a sentence of up to 15 years in prison. But the judge only placed Tom on probation.

Tom’s wife divorced him in the years that followed. He left Utah, remarried, and then, in 1995, police arrested Tom Jackson again, this time on charges of lewd conduct with a child under 16 years of age. He again pleaded guilty, but the Idaho judge showed none of the leniency the Utah judge had. Tom received a life sentence. But Tom’s no longer in prison, clearly. He won an appeal that reduced his sentence to 15 years. He served that time, a fact he and I discussed at the start of our interview.

Tom confided he felt a bit nervous going on tape. He hoped I wouldn’t make a monster of him. I promised to treat him fairly. And Tom acknowledged his past complicates how we might see him.

Tom Jackson: I wouldn’t doubt if I was a suspect and all that. And that’s ok with me.

Dave Cawley: Because, Tom says, he’s taken polygraph after polygraph as part of his probation.

Tom Jackson: And one of the questions in there is “you committed any other crimes that we don’t know about?” And when I said “no, not at all.” And it come up true, so.

Dave Cawley (to Tom Jackson): I mean, it’s—

Tom Jackson: Y’know, that pretty much cleared me right there.

Dave Cawley: —it’s a lot of years, right? You would think if you were a suspect, someone would’ve come and talked to you a long time ago—

Tom Jackson: Yeah, yeah.

Dave Cawley: —right?

Tom Jackson: That’s true.

Dave Cawley: After Tom Jackson left his job at the East Layton Police Department a year following Nancy Baird’s disappearance, the town hired a new officer, a guy named Dave Davis. Town leaders quickly promoted Davis to chief. Davis told The Salt Lake Tribune he was “working wonders” with the small budget provided to him in a 1977 newspaper story comically headlined “Yes, East Layton has a police department.”

Gary McFarland: They just did not have the funding to take and keep somebody.

Dave Cawley: Chief Davis also inherited the Nancy Baird case. He did nothing with it until, in 1979, four years on from Nancy’s disappearance, Davis hired a new patrol officer named Gary McFarland.

Gary McFarland: And it came down to where it was just me covering 12 hours and the other, the chief would cover the other 12 hours. And there was a promise from the city that if I did that, they would send me to the police academy.

Dave Cawley: Chief Davis gave Gary former East Layton police officer Dave Anderson’s report about the disappearance of Nancy Baird.

Gary McFarland: There just wasn’t a lot. We were, y’know, a very small community. There was very few things going on. Property disputes, loose cows, loose, loose horses. (Laughs) That kind of thing. It just, that was, that was a pretty big case.

Dave Cawley: At this same time, Ted Bundy was standing trial for murder in Florida.

John Hollenhorst (from July 24, 1979 KSL TV archive): As the verdict approached, reporters, editors and photographers prepared for the climax of the trial. The Bundy case has generated vast amounts of publicity all over Florida and in the western states of Utah, Colorado and Washington. In all those places, Bundy is suspected of murders. All involving young women.

Dave Cawley: Gary, and many others, believed Ted Bundy might’ve killed Nancy Baird. It wasn’t much of a leap: Bundy had been in Utah the summer Nancy disappeared.

Gary McFarland: She had the appearance of some, the females that he preferred. That’s all we had, is the method of operation fit.

Dave Cawley: But that suspicion didn’t give Gary any direction as to where to look for Nancy’s remains.

Gary McFarland: It was becoming a cold case, basically.

Dave Cawley: A little kerfuffle erupted in East Layton around this same time. The mayor fired police chief Davis, who responded by telling the news media it was an attack on the entire department.

Dave Davis (from March 24, 1980 KSL TV archive): They may be looking into an outside agency to contract to and dissolve the police department as a whole.

Dave Cawley: I suspect you probably don’t much care about this small town political squabble, but I promise you, it’s relevant to the Nancy Baird case because of what happened in the end.

Gaylen Young (from March 26, 1980 KSL TV archive): Nearly 400 angry residents were in attendance at the city council meeting because mayor Delin Yates was not going to keep police chief Dave Davis on the job.

East Layton resident (from March 26, 1980 KSL TV archive): We don’t want a contract with Davis County. We don’t want a contract with Layton City. We want the police force we have with the responsible, interested service that we get from them.

Dave Cawley: This protest proved ineffective. East Layton dissolved its police department. Officer Gary McFarland, fresh out of the academy, no longer had a job. But it didn’t stop there. The residents of East Layton voted to disincorporate at the end of 1980. Their town ceased to be and neighboring Layton City swallowed it whole. The records of the East Layton police department were lost to time. All except for the report of former police officer Dave Anderson about the disappearance of Nancy Baird. Gary McFarland still had it.

Gary McFarland: It ended up with me. No direction as to what to do with it. But it was in my custody.

Dave Cawley: But with East Layton gone, who would inherit jurisdiction over Nancy Baird’s case? Did it belong to Layton City, which absorbed East Layton? Or did the Davis County Sheriff’s Office bear responsibility, given the work deputies there had done assisting East Layton early on?

Gary McFarland: Davis County provided a lot of the crime scene investigations because small communities could not provide that service.

Dave Cawley: As we saw with the Sheree Warren case in Cold season 3, victims fall through the cracks when police agencies fail to communicate. And that’s what also appears to have happened with Nancy Baird. No one took the initiative. It wasn’t Gary McFarland’s case, but he felt duty-bound to safeguard the reports.

Gary McFarland: Because it was one of those cases that you knew someday would have a lead.

Dave Cawley: Gary ended up taking another police job at a different agency. Year after year, he waited for a phone call that might break the case.

Gary McFarland: Nobody ever came forward. Nobody was ever found. Not one tip, not nothing.

Dave Cawley: Gary McFarland retired in 2012. He turned the East Layton police report on Nancy Baird over to the Davis County Sheriff’s Office.

Gary McFarland: They’d come up with some other theories, besides the only one that I ever came up with.

Dave Cawley (to Gary McFarland): Bundy?

Gary McFarland: Yeah.

Dave Cawley: Is that what you mean?

Gary McFarland: Yeah, ‘cause I’m stuck on it. It will, until I’m proven different.

Dave Cawley: Gary still believes Ted Bundy is the most likely suspect in Nancy Baird’s presumed murder. But he knows that’s not the only theory.

Gary McFarland: The theories were that it was possibly a law enforcement officer that worked in East Layton.

Dave Cawley: The story we’ve heard so far leaves me deeply skeptical about any conclusion regarding Nancy Baird’s death being the work of serial killer Ted Bundy. To my mind, there are too many other plausible scenarios. And, Tiffany Jean, the archivist, told me she’s unsure as well.

Tiffany Jean: I, I looked at the case a little bit. And I thought that it didn’t quite fit his M.O., with what I know about how he operated.

Dave Cawley: What was different? For one, the location. Ted Bundy was never known to abduct a woman from a gas station during daylight hours.

Tiffany Jean: And while Bundy was capable of doing that, he mostly operated at night. And he mostly avoided places where he could be seen or picked out.

Dave Cawley: In his early crimes in Washington state, Bundy sometimes approached women while claiming to be injured, needing help to put something in his car. Would Nancy Baird have taken that kind of bait?

Tiffany Jean: It seems unusual that she would have been willing to leave her post to do that when there was no one else at the station.

Dave Cawley: Bundy liked to lure women to his car—a light tan 1968 Volkswagen Beetle—then handcuffed them or knocked them unconscious. If he’d done something like that with Nancy Baird, it probably would’ve happened right in the parking lot outside the Fina station.

Tiffany Jean: And that seems like kind of a big risk for Bundy to have taken.

Dave Cawley: None of the witnesses from the Fina station reported seeing a Volkswagen Beetle like Bundy’s. And the descriptions provided by the Williams children didn’t match Ted Bundy, either.

Tiffany Jean: So, that’s another reason that seems unlikely that it would have been him.

Dave Cawley: Nancy Baird vanished from the Fina station within the space of just five or ten minutes.

Kenny Payne: Yeah I mean she’s just, she’s just gone.

Dave Cawley: No signs of a struggle, no indication she ran away.

Kenny Payne: I mean she’s got a, a child at home.

Dave Cawley: So retired sheriff’s detective Kenny Payne gets why even some of his former colleagues believe to this day Ted Bundy abducted and murdered Nancy Baird.

Kenny Payne: But then you have to try and figure out whether or not the first thought of “it’s gotta be Ted Bundy” well no, what can you find that tells me a story?

Dave Cawley: What Kenny’s saying is the elements necessary to build a narrative about Ted Bundy killing Nancy Baird just aren’t there.

Tiffany Jean also shared another, more compelling reason why she questions Ted Bundy’s supposed involvement. Bundy, she told me, might have an alibi for the day Nancy Baird disappeared. And Tiffany could be the first person to ever piece it together.

Ted Bundy first moved to Utah in September of 1974, having come from Washington state to attend law school at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Tiffany Jean: He had a steady girlfriend who lived in Seattle who was originally from Ogden. And she was probably the reason why he came to Utah in the first place, because she had roots there. And eventually they planned on settling down there, if they ever got married. But y’know, he was not a good person. (Laughs) So in addition to everything else bad that he did, he also cheated on her quite a bit.

Dave Cawley: In June of 1975, just a few weeks before Nancy Baird disappeared, Ted Bundy met a young school teacher named Leslie Knudsen at a party in Salt Lake City. Bundy and Leslie started seeing one another.

Tiffany Jean: And they dated until August, she saw that he was arrested and didn’t want anything more to do with him.

Dave Cawley: Leslie spoke to investigators back in 1975, but she was never called as a witness in court and has kept a very low profile all the years since. Her story is not well known, even among Ted Bundy experts.