Dave Cawley: A human skull rolled down a brushy hill between a suburban neighborhood and a busy Utah highway. The cranium came to rest in a litter of decaying leaves, at the base of a barren scrub oak tree. It sat there for some time — hours, days, months — before a man walking his dog caught a glimpse of it.

DeAnn Servey (from February 5, 2015 KSL TV archive): The man who initially found it, uh, walks along this Frontage Road every day and noticed something in the bushes.

Dave Cawley: He wasn’t sure what it was at first, just that it appeared round and off-white: out of place amid the drab remains of last autumn’s long-fallen foliage. But it’d captured his curiosity. So, he went in for a closer look. Only then could he see the unmistakable shape of the hollow eye sockets, the six teeth still stubbornly lodged into the maxilla. This was once the head of a living human being. But judging by the brittle appearance of the bone, this person had been dead for quite some time. The man, recognizing the skull as the partial remains of a person, recoiled, then pulled out his phone and called 911.

Davis County sheriff’s deputies rushed to the site. They put up crime scene tape as the frigid dark of the February night descended. A sergeant fielded questions from curious reporters, her face lit by the hard lights of the TV cameras, her breath turning to fog in the chill.

DeAnn Servey (from February 5, 2015 KSL TV archive): You don’t know if an animal could’ve brought it from a different location. There’s so many factors that we’re going to try to piece together and find the origin of this skull.

Dave Cawley: In other words, they didn’t know much. In the days that followed, crime scene technicians scoured the hill for more bones. They uncovered a shallow grave at the top of that hill, just a few feet behind the backyards of several homes. The grave contained the skeletal remains of a young woman.

Guy Beynon (from February 6, 2015 KSL TV archive): It was a little disturbing to, to realize that there’s a, parts of a, remnants of a body there.

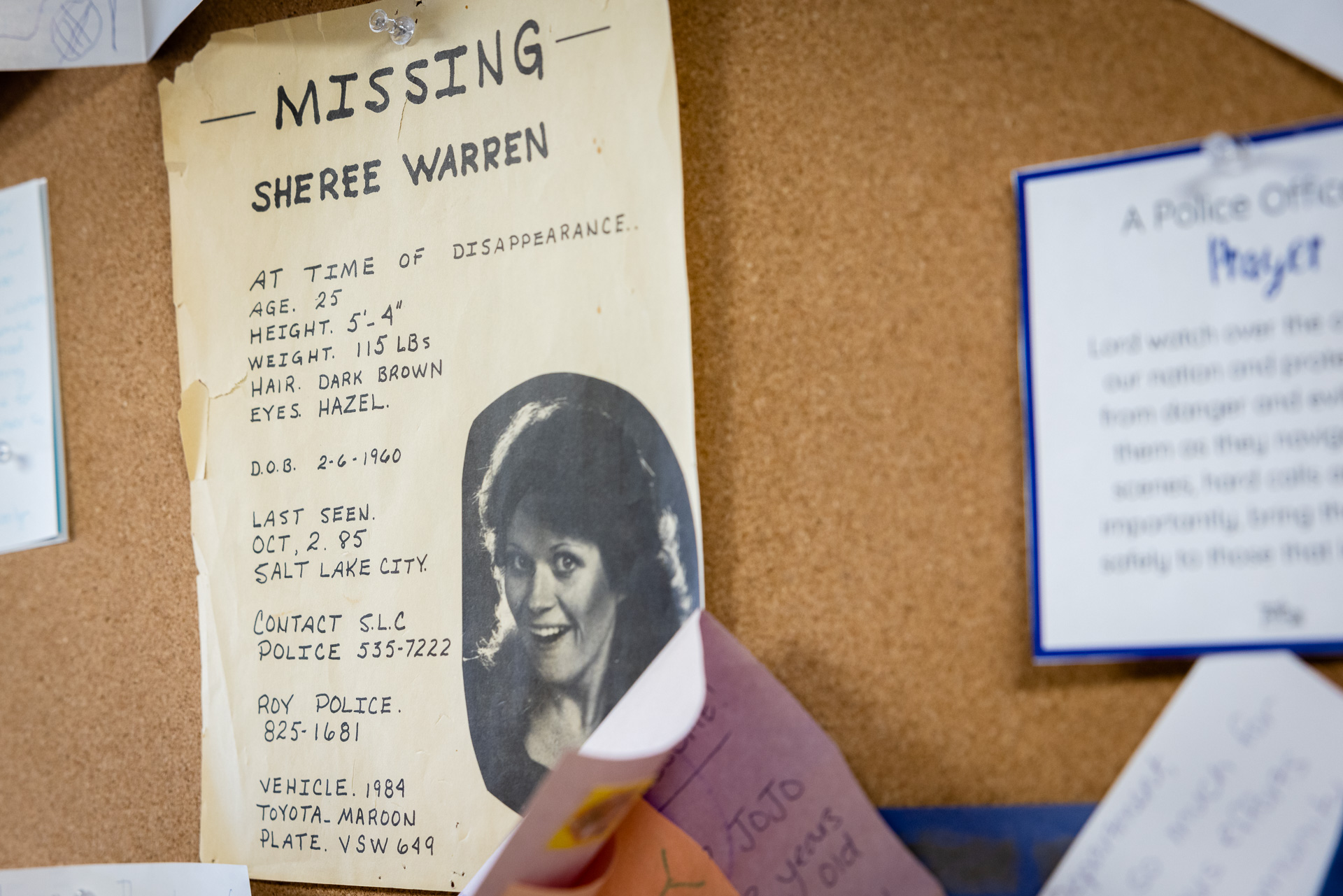

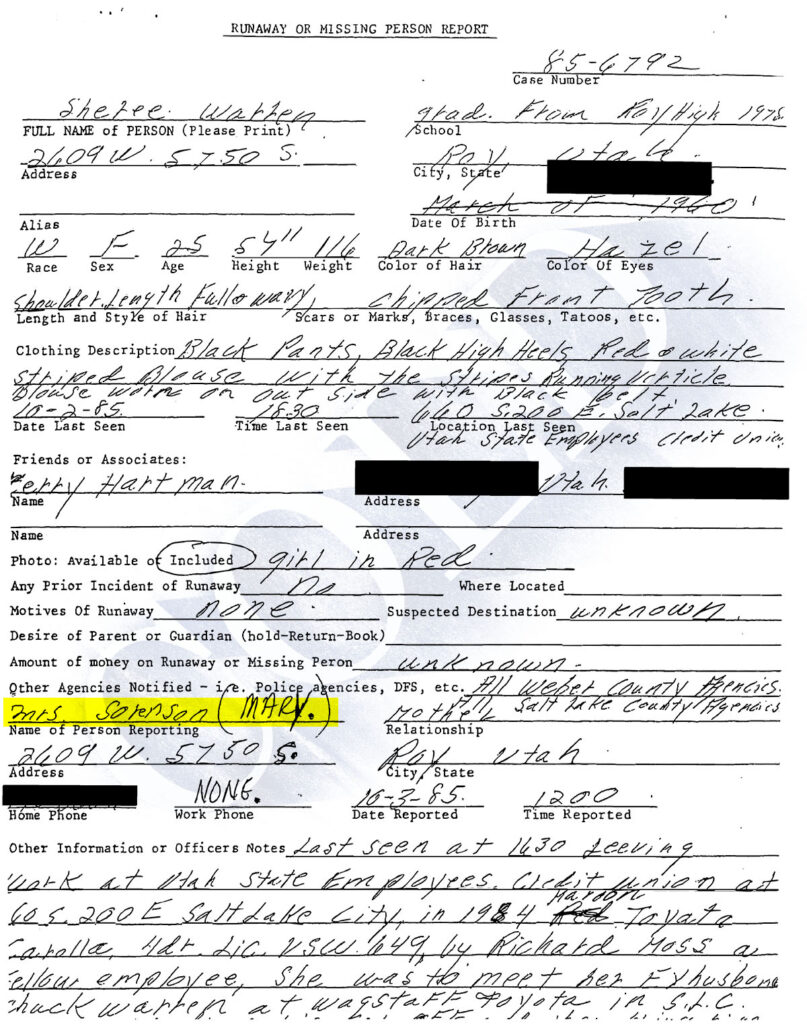

Dave Cawley: This discovery of a clandestine gravesite in early 2015 along U.S. Highway 89 between Salt Lake City and Ogden resulted in police agencies all across Utah questioning if the bones belonged to one of their missing people. Police in the city of Roy hoped the skull might belong to Sheree Warren. The grave sat midway between where Sheree had lived, and where she’d disappeared.

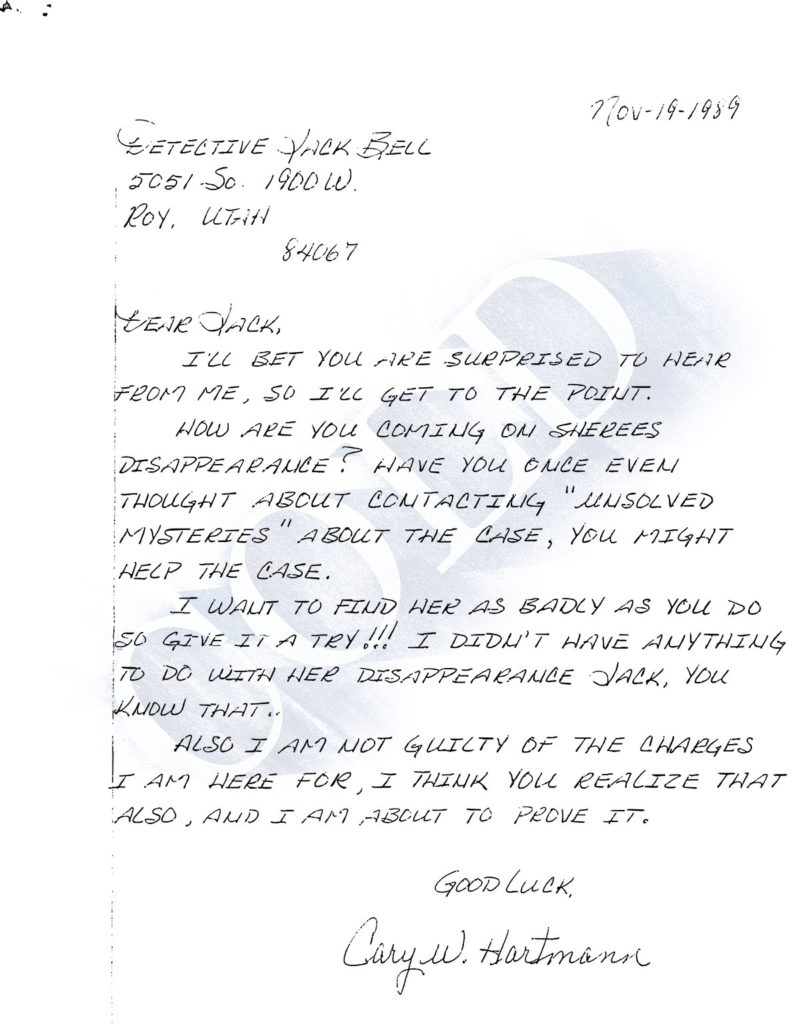

Jack Bell, the original investigator on the Sheree Warren case, had retired six years earlier, in 2009, as assistant chief for the Roy City Police Department. He’d never stopped wondering what’d happened to Sheree.

Jack Bell: The last time I talked to anybody out here about that case, they had a pretty good size cardboard box full of stuff.

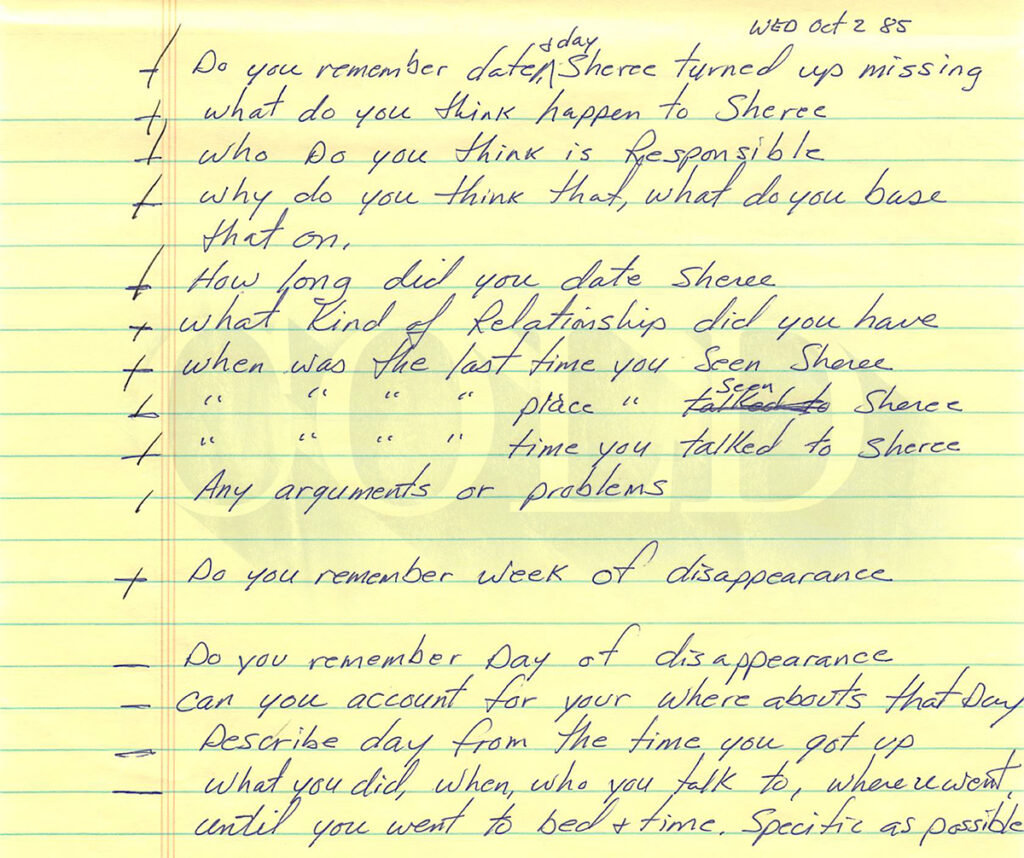

Dave Cawley: That “stuff” included Jack’s handwritten notes. Jack told me he’d at one time tried to type those chicken scratches into a computer.

Jack Bell: ‘Cause I wasn’t very proud of the work and I know my handwritings terrible. But, uh, I didn’t get very far, so…

Dave Cawley: …so the notes had gone back into the box and the box had gone onto a shelf, all but forgotten. It’d collected dust, until that skull rolled down a hill next to a busy highway between Salt Lake City and Ogden.

John Frawley: I was just in my office one day and my supervisor comes in with a box, one of those cardboard boxes and he said “hey they found, uh, remains in Davis County. So we’re reopening this cold case.” It was Sheree Warren and I didn’t, I honestly didn’t know much about the Sheree Warren case at all.

Dave Cawley: That’s the voice of detective John Frawley. He’d started with the Roy City police department in 2008, meaning his and Jack Bell’s paths crossed only briefly. John’d only been a cop about six years when he ended up with Jack Bell’s old box of Sheree Warren case files. He was still relatively new to investigations, but had a sharp, analytical mind.

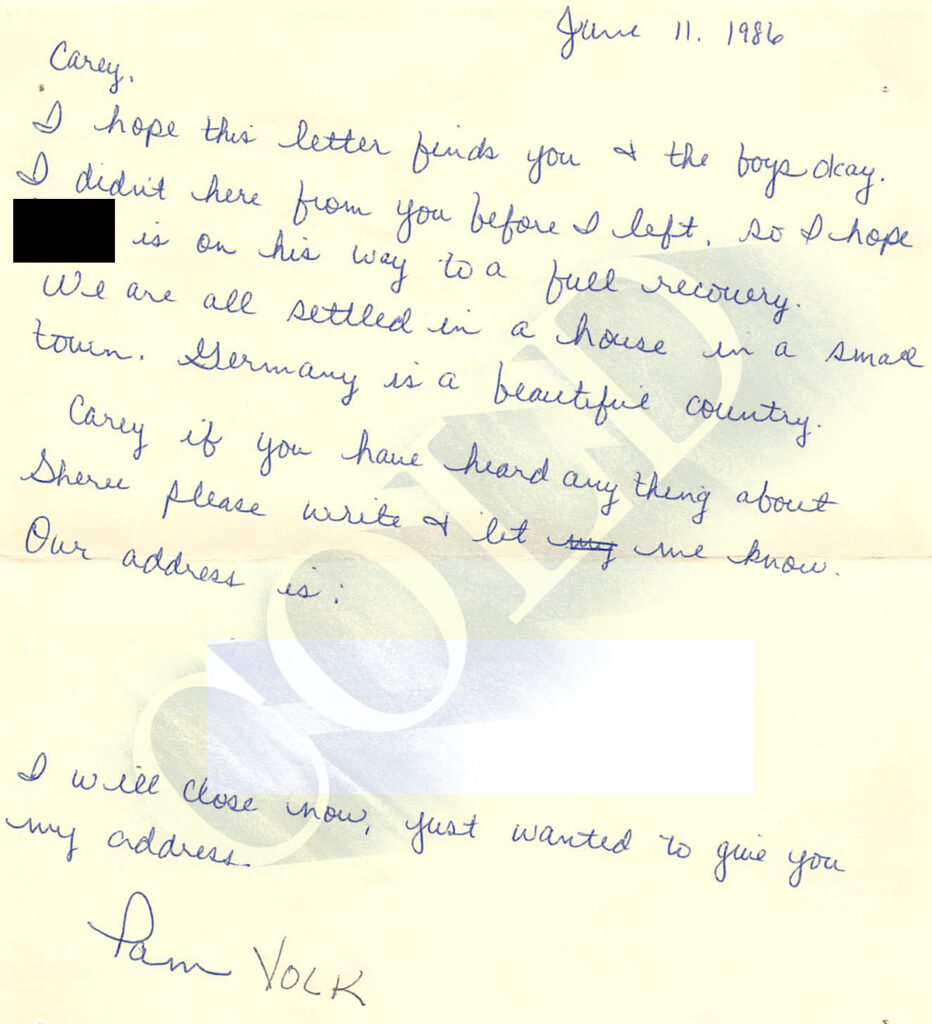

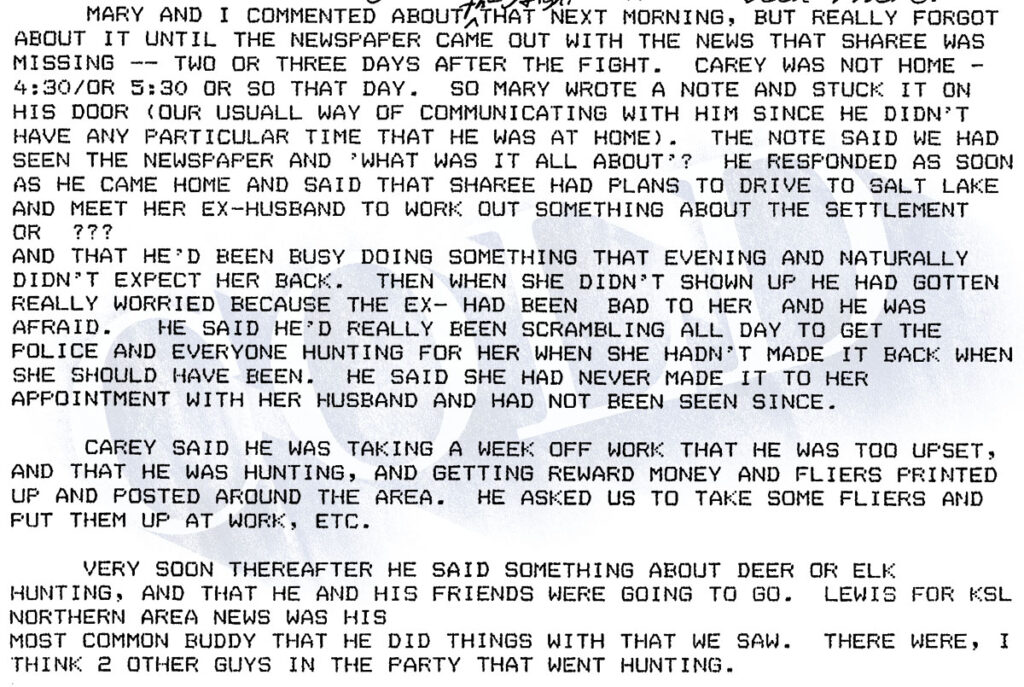

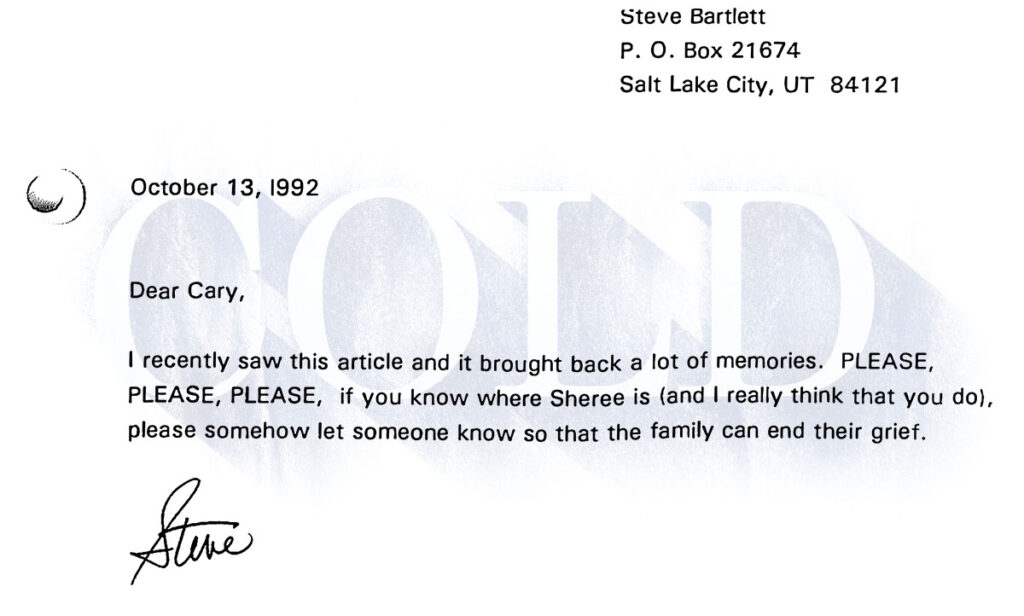

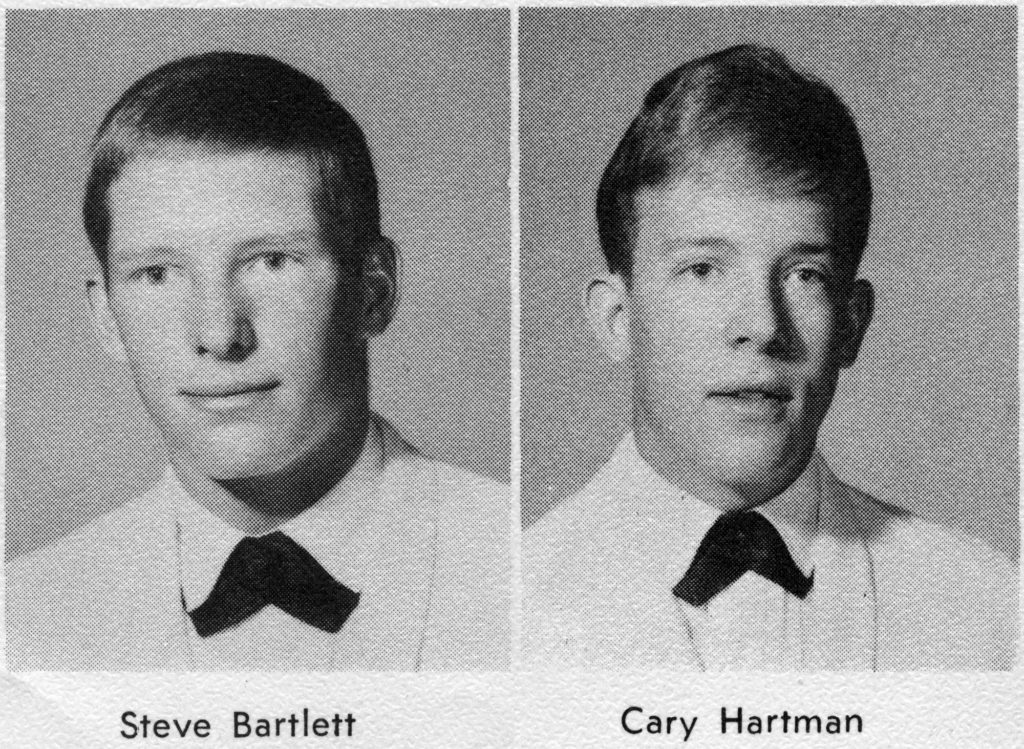

The box contained Jack Bell’s notes, a copy of the statement Cary Hartmann had given to his private investigator, reports from Las Vegas police about the discovery of Sheree’s car and a few other tidbits. John told me he’d seen Sheree’s face hundreds of times, without ever realizing it.

John Frawley: Sheree Warren’s picture was actually in a display case in our lobby and, uh, I never made the connection.

Dave Cawley: John’d never stopped to study that old missing persons flier. It looked a lot like the one Cary Hartmann had carried into Jack Bell’s office almost 30 years earlier. The box also contained one of those old fliers Cary Hartmann had printed. John looked at it, seeing again the photocopied picture of a smiling Sheree Warren. He picked through rest of the cardboard box, pulling out Jack’s notes, struggling to decipher the former detective’s handwriting. John read the original missing person’s report. It described how Mary Sorensen had called police the day after Sheree failed to return home from work one October evening.

John Frawley: Mary really kept her finger on the pulse of the case, y’know, and was involved.

Dave Cawley: John decided Roy police needed to reconnect with Sheree’s relatives.

John Frawley: I met with some of Sheree Warren’s family members and just to collect some DNA so we had something to compare to.

Dave Cawley: In the process, he learned Sheree’s mom, Mary, had died about two years earlier.

John Frawley: Umm, I was, I was never able to meet her and talk with her.

Dave Cawley: But he did meet Sheree’s dad, Ed Sorensen, as well as her son.

John Frawley: In talking with, with her son, he asked about that. He said, y’know, “is her picture still out in the lobby?” And I was, I said “yes.” And y’know, it’s important to them.

Dave Cawley: These interactions drove home to John just how frustrating the years with no answers must’ve been to the people who cared most about Sheree. So, John went back to that banker’s box of old case notes and reports.

John Frawley: Yeah, literally. Taking it off the shelf, yeah.

Dave Cawley: The box didn’t have everything, only a fragment of the Sheree Warren case, covering the first year-and-a-half of the investigation. That’s because, as I’ve mentioned before, the case had been split between investigators from Roy, Ogden and Salt Lake City. So, John didn’t yet have a full picture of the case but he found himself fascinated by what he’d seen.

John Frawley: I was taking it home and reading it, y’know it was just, I was hooked on it.

Dave Cawley: Yeah, I know the feeling, John. Meanwhile, the Office of the Utah State Medical Examiner was trying to identify the bones found on that hillside. John sent the medical examiner one of the items he’d found in the box — Sheree’s dental records — for the sake of comparison.

John Frawley: Everything sort of fit. Meaning, the timeframe, it was a female, it was the same stature that Sheree Warren was.

Dave Cawley: Sheree’s case had been dormant nearly a decade when the discovery of these skeletal remains infused detective John Frawley with a desire to find answers for Sheree’s family.

John Frawley: And I felt like, I felt like there was more I could do on it. As an investigator, that’s what you’re driven to do, y’know, dig in.

Dave Cawley: This is Cold, season 3, episode 9: A Picture in the Lobby. From KSL Podcasts, I’ve Dave Cawley.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: Roy police detective John Frawley had picked up the Sheree Warren cold case in February of 2015, after the discovery of unidentified skeletal remains in a clandestine grave.

John Frawley: I started reading through this information in this box, and that’s how the cold case started.

Dave Cawley: John couldn’t get Sheree’s case out of his head. He’d done some preliminary research and re-established contact with Sheree’s family, but he wanted to do more. So, he’d gone to talk to his boss.

Carl Merino: Carl Merino. C-A-R-L and Merino, M-E-R-I-N-O.

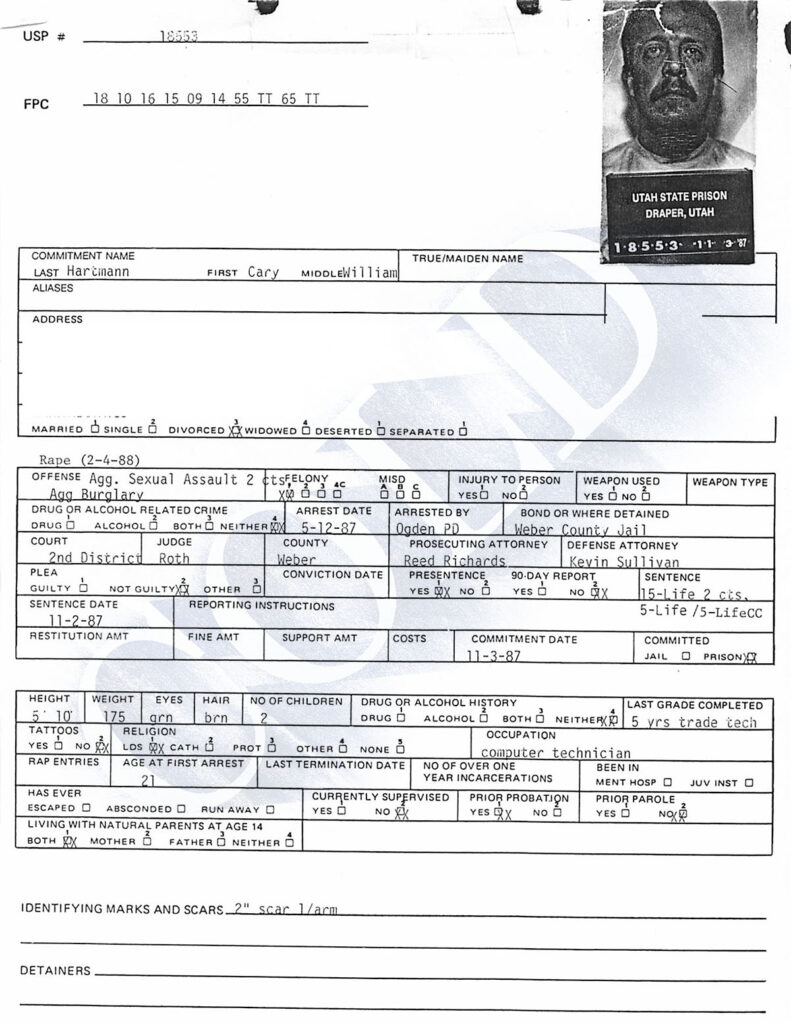

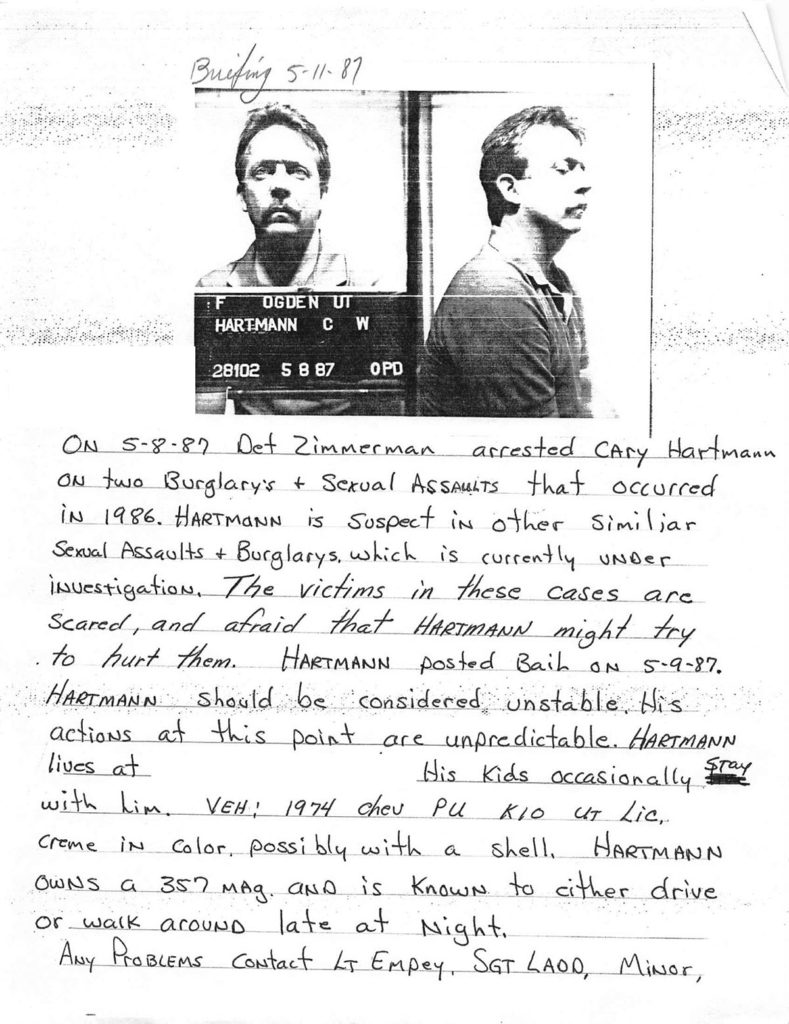

Dave Cawley: Carl Merino served as chief of police for Roy from March of 2015 to May of 2021. We’re going to spend a little time diving into Carl’s background now, to help you better understand his philosophy on cold cases. It’s important because it shows why he was willing to green light John Frawley’s continued work on the Sheree Warren case. And he’d bumped up against the Sheree Warren case — and one of the two suspects, Cary Hartmann — several times over the years.

Carl Merino: It’s been really interesting to think how that case and my career have interacted.

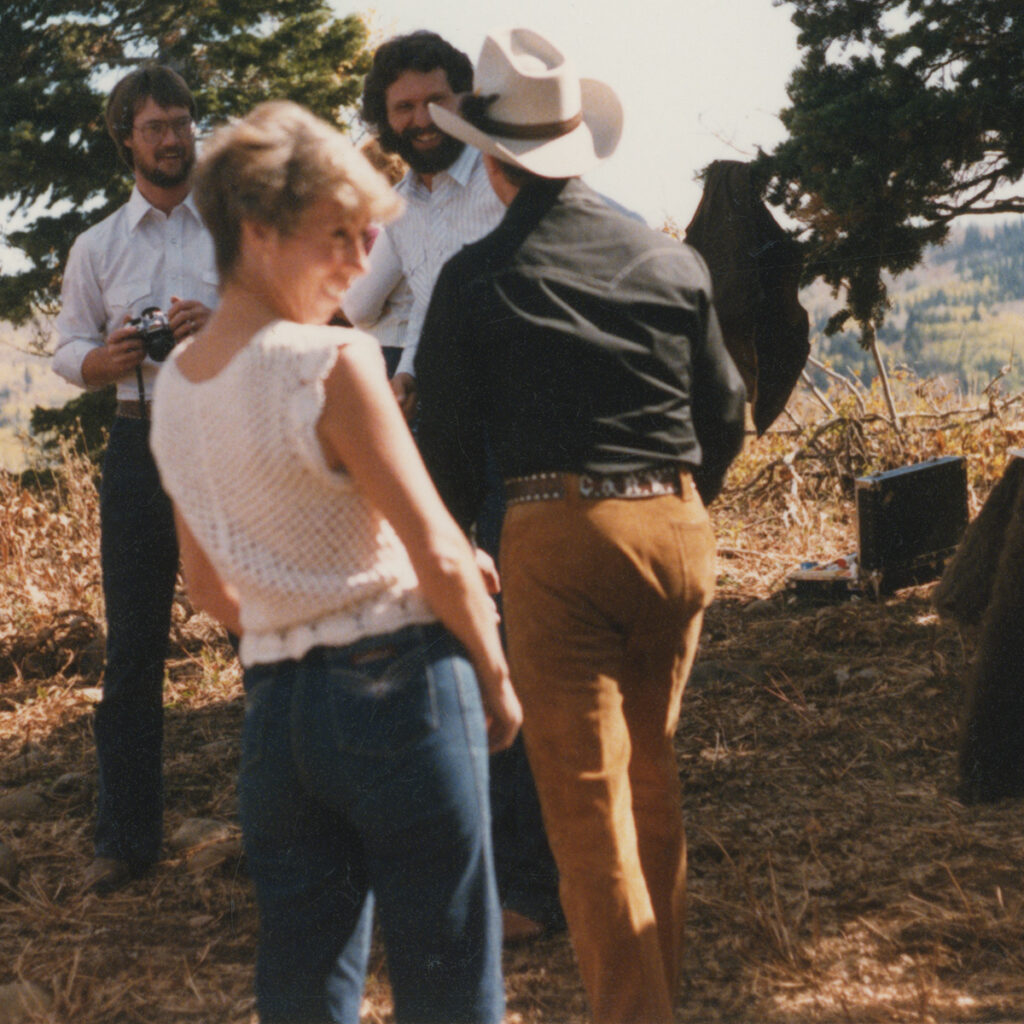

Dave Cawley: So let’s look at Carl Merino’s history with the Sheree Warren case. Carl started as a cop in 1983, when he took an unpaid, volunteer position as a reserve officer with the Ogden Police Department. He signed onto the reserve corps right after Ogden police brass kicked Cary Hartmann out of it. Carl told me he’d known Cary back then, from his day job.

Carl Merino: He would come in where I worked as an industrial supplies sales rep and so I knew him from there. We had talked a little bit, but not much. He was a really outgoing guy. Uh, came across always as very confident. You got the feeling that he thought he was better than everybody else. And kind of that feeling of he had a scam going everybody. You know how somebody’s always getting over, that was kind of the way he came across.

Dave Cawley: It wasn’t until a few years into Carl’s time as an Ogden reserve officer that he came to see Cary Hartmann in a different light.

Carl Merino: I was at work the one day and I got called by our coordinator who coordinated with the reserves and he said “I need you to come to the police station and bring your gun.” And that usually means you’ve done something wrong and y’know, they’re taking your gun away and y’know, not let you volunteer anymore. And I thought “I can’t think of anything I could’ve done that would’ve done that.” So I went home and got it and took it up to Ogden Police Department and he said “your gun was issued to Cary Hartmann when he was a reserve with Ogden. And he has intimated that he used a gun with several of his rapes and we’re thinking it was probably this gun so we’re taking it back to use as evidence in case we, we can actually prove something with that.”

Dave Cawley: He only knew from reading the newspaper Cary’d also been dating Sheree Warren when she’d disappeared.

Carl Merino: Y’know it’s easy to imagine that something happened between the two of them that got out of hand.

Dave Cawley: Two years later, Carl took a full-time, paid position as a police officer.

Carl Merino: August of ’89, I got hired with Roy PD.

Dave Cawley: By that point, the Sheree Warren case was already four years old and well on its way to going cold. Five more years went by before, in 1994, Carl switched departments. He became a detective for Salt Lake City.

Carl Merino: I was assigned to homicide. And while I was assigned there we started to, to work cold cases.

Dave Cawley: Carl had arrived in Salt Lake right at the end of that department’s search for a suspected serial killer, a search that’d soaked up a lot of money and manpower without much to show for it.

Carl Merino: Nothing was getting solved.

Dave Cawley: As we’ve already seen in past episodes.

Carl Merino: I was assigned to, to look into some of those cases from the mid-‘80s. And that’s the same time that Sheree Warren went missing from Salt Lake.

Dave Cawley: Carl saw how jurisdictional politics had made Sheree’s case a hot potato from the start.

Carl Merino: The last place she was known that people knew where she was was Salt Lake so the case should’ve been handled out of Salt Lake, uh, but they said “no, she’s a Roy citizen and so we’re not gonna work it.”

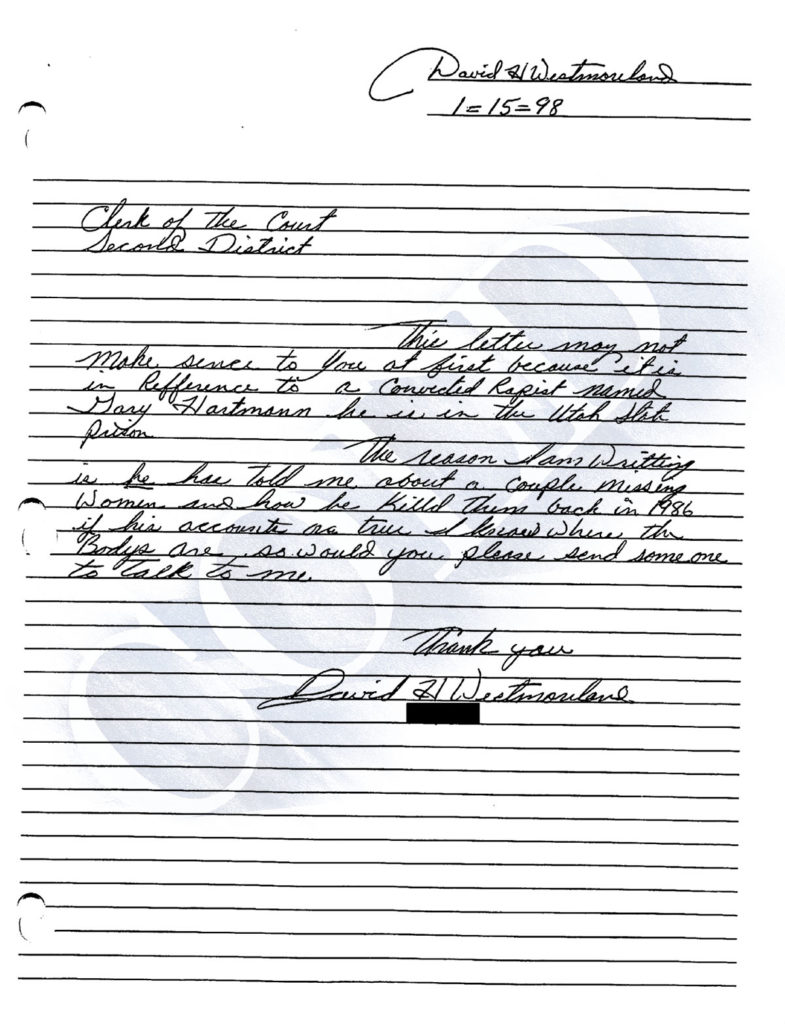

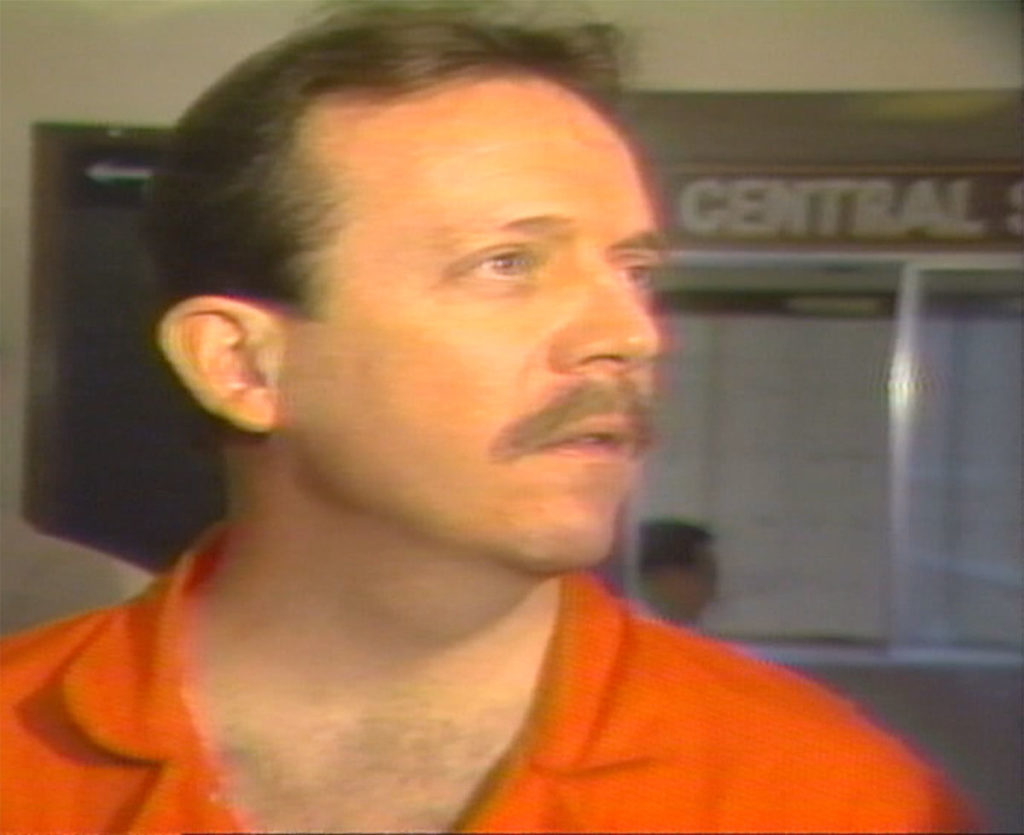

Dave Cawley: Roy police detective Jack Bell had worked Sheree’s case for a few years, before handing it off to the Ogden Police Department, where it promptly went cold. Ogden detective Shane Minor had picked Sheree’s case up again in 1998, honing in on Cary Hartmann as his lead suspect.

Carl Merino: And so they thought that there was a connection there since he was, y’know, a convicted rapist as well.

Dave Cawley: But Shane’s investigation had itself stalled in 2006, leaving Sheree’s case cold once again. All the information Shane’d gathered up to that point remained with him. His report didn’t find its way into the hands of Salt Lake detectives, like Carl Merino. Shane told me he’d taken part in a few cold case conferences over the years. He’d presented the Sheree Warren case, hoping to drum up some help.

Shane Minor: You put a bunch of guys together, a bunch of cops especially and everybody’s gonna have great ideas but then there’s the follow-through of “ok, who’s gonna do what?” And “make sure this gets done.”

Dave Cawley: It’d felt like doing a group project in school: a lot of people had great ideas, but no one seemed interested in doing the actual work. Years passed. Carl Merino was approaching retirement from his job in Salt Lake City when one day he saw yellow crime scene tape out of the corner of his eye while driving home from work.

Carl Merino: The body on the east side of the, of 89.

Dave Cawley: The spot where the dog walker had found that skull.

Carl Merino: I was still in Salt Lake they found her.

Dave Cawley: Carl followed the news of the discovery, wondering if the bones might belong to Sheree Warren.

Mike Headrick (from March 12, 2015 KSL TV archive): Deputies aren’t saying who they’ve questioned in this current case and they’re not disclosing the cause of death at this time.

Dave Cawley: Dental records allowed the medical examiner to identify the skeletal remains as those of a missing woman, who’d disappeared during the 1980s. But the medical examiner told detective John Frawley the bones did not belong to Sheree Warren.

John Frawley: The remains were later identified as Theresa Greaves.

Mike Anderson (from March 12, 2015 KSL TV archive): She was 23 years old when she disappeared back in 1983 and right now deputies here in Davis County are investigating this as a homicide case.

Dave Cawley: If this sounds familiar, it’s probably because the discovery of Theresa Greaves’ remains also came up in Cold season 2. We don’t have time to repeat Theresa’s story here, but I’ll note her case still remains unsolved.

Mike Headrick: Greaves had left her home in Woods Cross and told a roommate that she was taking a bus into Salt Lake City for a job interview.

Dave Cawley: Salt Lake detectives had at the time declined to work Theresa’s case, leaving it to investigators in the much smaller suburb of Woods Cross, where Theresa’d lived. Why did the Salt Lake detectives turn their back on Theresa in the 1980s? Perhaps a mixture of big-city cop elitism and a desire to keep their crime stats down. The majority of missing persons cases resolve quickly with the missing returning home. But those that don’t, like Theresa Greaves’ case, can linger for decades.

Carl Merino told me Salt Lake detectives did the same thing two years later, with Sheree Warren’s case. They pushed that investigation off onto the Roy police department. But Roy did not at the time have the resources to conduct a robust investigation 40 miles away.

Carl Merino: I wonder if they spent the time in Salt Lake to gather all the evidence down here that they could have.

Dave Cawley: Carl’d started out in Roy, then gone to work in Salt Lake City. He’d seen both sides of the coin over the course of his career. But that career took an interesting turn in March of 2015, just weeks after the discovery of those skeletal remains on a hillside next to the highway. Carl Merino returned to the Roy City Police Department.

Carl Merino: They had an opening for Chief of Police and I applied and, uh, they selected me.

Dave Cawley: And so that’s how Carl became detective John Frawley’s boss, just weeks after Frawley’d re-opened the Sheree Warren cold case.

John Frawley: I did have one supervisor say, y’know, after, after the remains were identified “well ok, well we’re, we’re done, we can kind of just move on.” But there was a separate supervisor said “y’know, you don’t have to put that back on the shelf, you can still work it.” And that’s what I wanted to do. I just felt like there was more to do on it.

Dave Cawley: Carl told me he believes cold cases matter. And as chief, he vowed to put money and manpower behind that belief.

Carl Merino: Detective Frawley came to me and said “are you ok if I work this Chief?” And I said “yeah, y’know, let’s get going.”

Dave Cawley: Detective John Frawley had both a personal desire and a mandate from his new boss to dig into the Sheree Warren case. He started by examining the facts: what did he know for sure about Sheree’s final day?

John Frawley: What did she plan on doing? She planned to meet Charles Warren at Wagstaff Toyota and give him a ride back to Ogden.

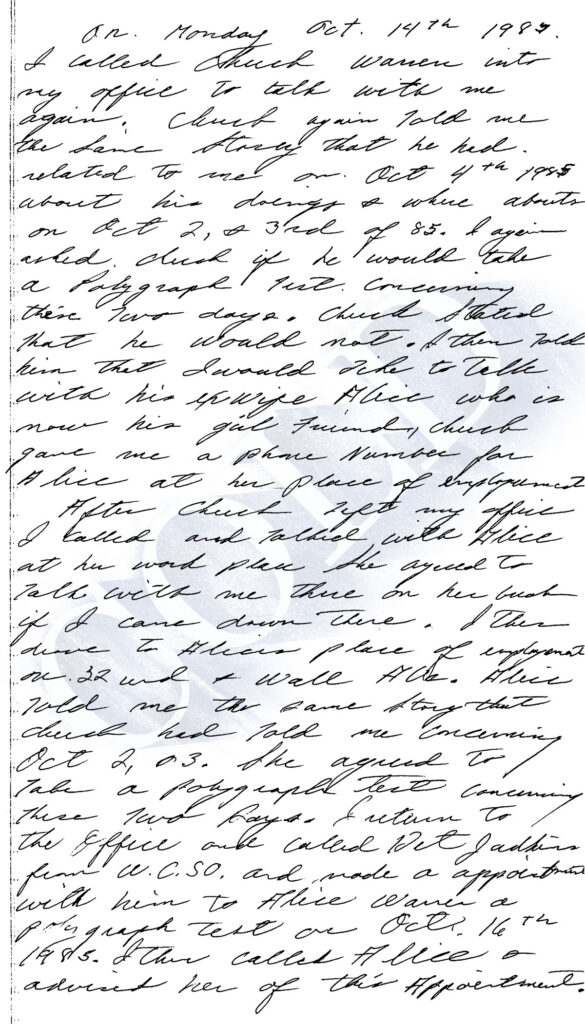

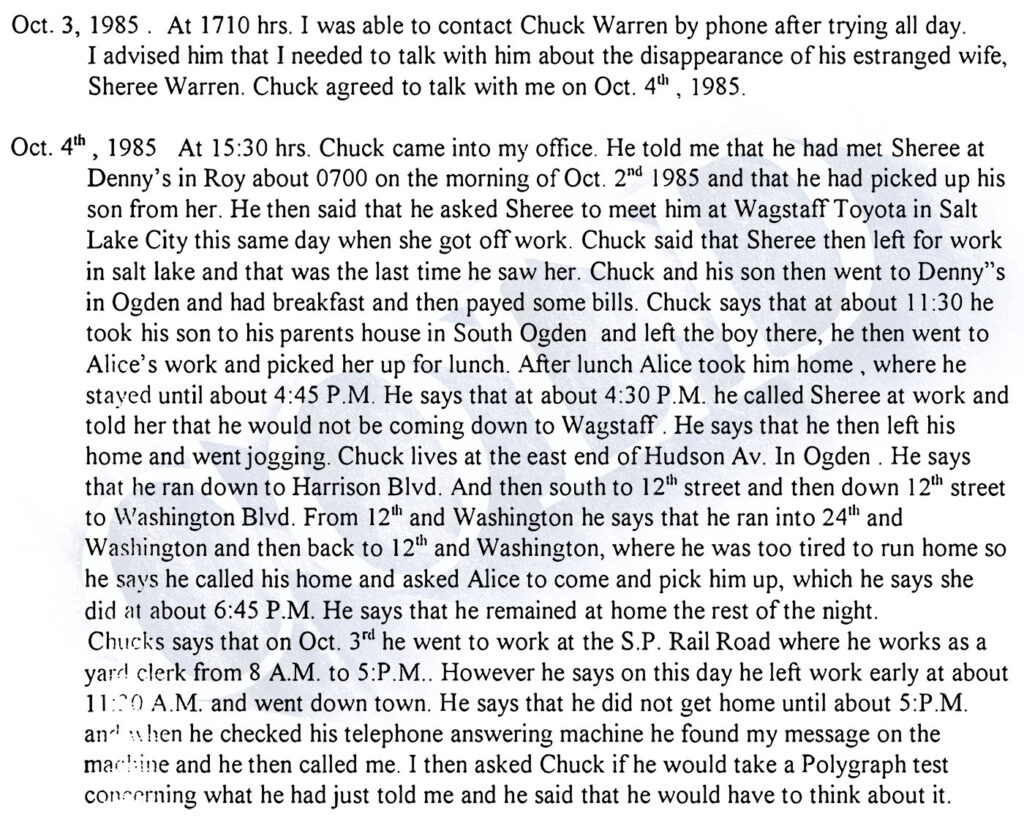

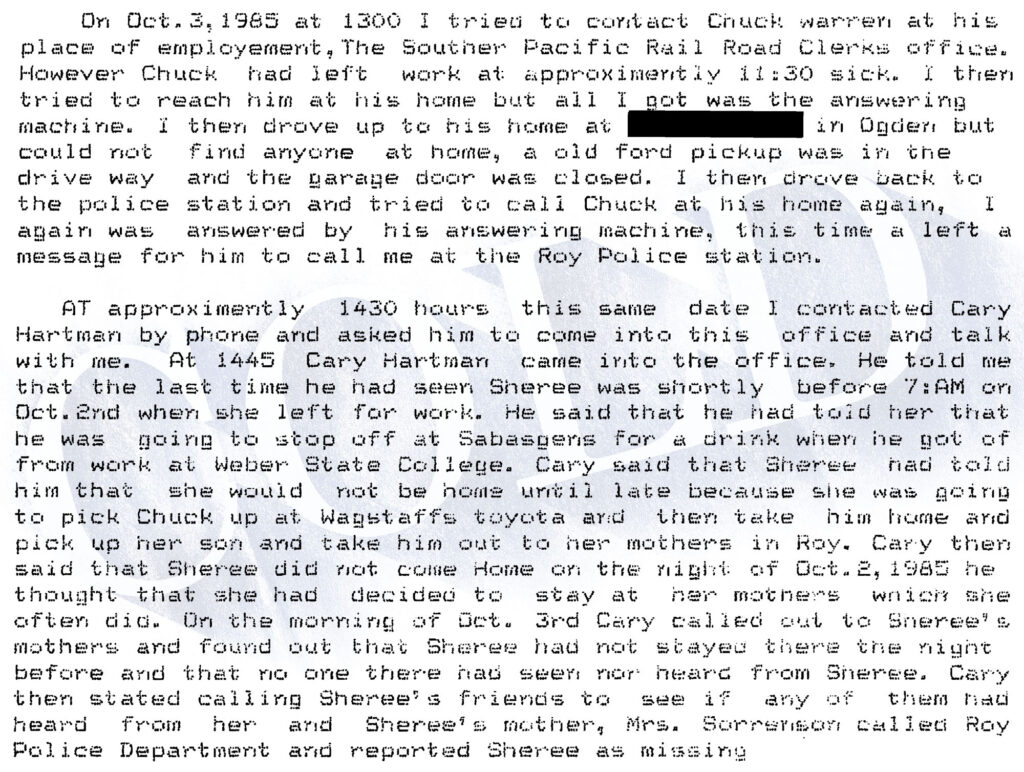

Dave Cawley: John knew from reading detective Jack Bell’s notes Chuck Warren had talked to Jack a couple of times.

John Frawley: He told detective Bell he never made it to Wagstaff’s. He became ill, he went for a jog. At the end of that jog he was too tired to go home and he called his previous wife, Alice, to come pick him up. Umm, to me that, that makes no sense at all.

Dave Cawley: It seemed like a shaky alibi. In John’s mind, Sheree’s ex-husband also had motive.

John Frawley: There’s a divorce. They’re in the process of a divorce. So there’s a house, a pension, a child. All these things are involved.

Dave Cawley: John could see a hypothetical scenario in which Chuck Warren killed Sheree in an act of domestic violence, seeking to put a quick end to their fight over alimony and child support. But did Chuck have opportunity?

John Frawley: The last person to see Sheree Warren was a co-worker whose name was Richard Moss.

Dave Cawley: We met Richard in episode 2. He was the credit union manager Sheree’d been training the day she disappeared.

Richard Moss: I never saw what car she got into or, her own car or another car or (laughs). I never saw her again.

Dave Cawley: John called Richard in June of 2015.

Richard Moss: And he wanted to know or refresh or see if, what I could remember.

Dave Cawley: It marked Richard’s third round of questioning over a span of nearly 30 years: first by Jack Bell, then by Shane Minor and now by John Frawley.

Richard Moss: Three conversations over the telephone.

Dave Cawley: Richard lived in Richfield, a rural community about 200 miles from Roy. He told me I was the first person in nearly 40 years to come interview him face-to-face about Sheree Warren.

John Frawley: Interestingly enough, I did speak to Richard Moss. He never did see Sheree get in her car.

Dave Cawley: Richard’s story remained consistent from the start, through his telephone conversation with detective John Frawley and my eventual meeting with him in 2021.

John Frawley: He was of the understanding that Sheree was gonna leave work and pick up her ex-husband give him a ride back home to Ogden.

Dave Cawley: Chuck Warren had said he’d called off that meeting. But that’s not what Sheree’d told Richard as they’d parted ways that evening in the garage behind the credit union office.

John Frawley: I need to get past this plan that she had to meet him.

Dave Cawley: John came across a report in the box of Roy police records. It talked about a tip that’d come in about four months after Sheree disappeared. A credit union employee had told police Chuck Warren’d made a cash advance on his credit card, in person, in Salt Lake City, on the day of Sheree’s disappearance. If that was true, it would mean Chuck’d lied about where he was that day.

John Frawley: Charles Warren was asked by detective Bell, if he would submit to a polygraph regarding his alibi.

Dave Cawley: And as we know, Chuck Warren’d refused that lie detector test. The tipster had told police she’d also heard Chuck’d made credit card transactions in Nevada, days before Sheree’s car surfaced in Las Vegas. I mentioned this tip in passing, way back in episode 2. But here, in 2015, detective John Frawley couldn’t find any indication his predecessor, Jack Bell, had ever verified it.

John Frawley: So, umm, that needs to be looked into.

Dave Cawley: John wrote a search warrant targeting Chuck Warren’s financial records. He wanted account statements, copies of checks or any details of transactions posted to Chuck’s account during September, October or November of 1985. A judge signed off on the warrant and John sent it to the credit union.

John Frawley: And a lot of that information was gone because of the timeframe.

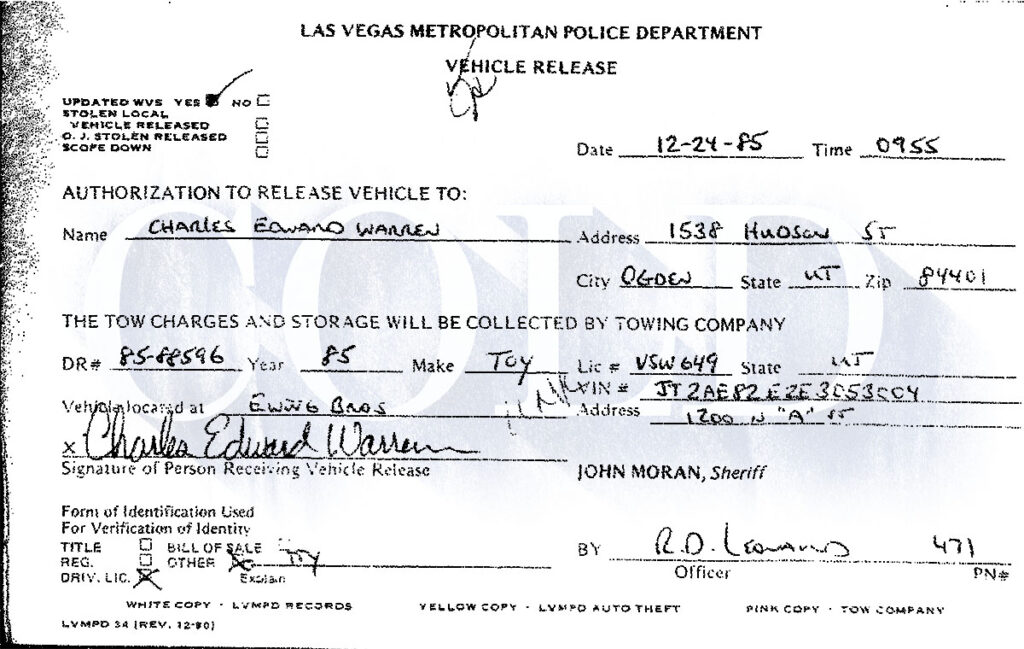

Dave Cawley: The credit union no longer had Chuck Warren’s checks. But it did have his credit card statements. I haven’t seen them, so I can’t tell you everything they revealed. But I do know the statements showed Chuck’d made a purchase in Elko, Nevada on November 4th, 1985 followed by another at the Circus Circus hotel and casino in Reno, Nevada on November 8th, 1985. That’s a little over a month after Sheree disappeared, and a matter of days before staff at the Aladdin hotel and casino in Las Vegas found her car abandoned in their back lot.

John Frawley: I felt that it was a significant development.

Dave Cawley: Because, John suspected, Chuck might’ve made those transactions while riding the train back to Ogden, after dumping Sheree’s car in Las Vegas. But, there were some problems with this idea. Las Vegas sits at the far southern tip of Nevada. Elko and Reno are in the north. They’re both nearly as far from Las Vegas as Ogden, Utah is. And there are no railroads directly connecting Elko or Reno to Las Vegas. And consider the timing. John’d read the Las Vegas police reports about the car’s discovery.

John Frawley: They say it looks like it’s been there for some time based on dirt, debris.

Dave Cawley: Chuck’s transactions occurred on November 4th and 8th. Sheree’s car turned up on the 11th. So that’s a week, a most, not long enough for the car to’ve gathered a thick coat of dust. So, Chuck Warren’s credit card transactions in Nevada probably didn’t have anything to do with dumping Sheree’s car in Las Vegas. But John still found them suspicious. So did I, frankly, when I first found out about them. I wondered if Chuck’d gone on gambling jaunts just weeks after his wife disappeared. If so, I didn’t expect to get a straight answer about it. In fact, I thought I’d never hear Chuck Warren’s side of the story. Turns out, I was wrong.

[Ad break]

Dave Cawley: Roy city police detective John Frawley drove into Ogden on June 23rd, 2015. He carried a small voice recorder in his pocket, and he started it rolling as he pulled up to the curb outside an orange brick house. John stepped out of his car and walked past the driveway, noticing an old Toyota Supra parked there. He headed to the front door.

(Sound of knocking on a door)

Dave Cawley: John had come alone to the house belonging to Chuck Warren. The same house Sheree Warren had herself called home for a few brief years back in the early ‘80s. But it was a different woman who greeted John at the door.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Hi, how are you?

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Good.

Dave Cawley: The microphone on John’s audio recorder sometimes rubbed against his clothing as he moved, making a lot of noise. So I’ll just tell you, the woman who answered the door identified herself as Willow, Chuck Warren’s wife. A cat slinked between Willow’s legs as she told John Chuck was in the other room.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): He was just getting his shirt buttoned up, so.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Awesome.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Come on in, Chuck. (Cat meows) What? No, you’re not going outside. (Cat meows)

Dave Cawley: The house looked much the same as it had when Sheree’d lived there more than 30 years earlier: same carpet, same everything. Only now, Willow lived there as Chuck’s wife, instead of Sheree. Chuck had met Willow Hendricks at a restaurant in Ogden called “The Stagecoach” in the late 2000s. He was a regular customer, she was working there as a server. They had a significant age gap — 27 years — but hit it off and began dating. Willow’d soon moved in with Chuck. They were married in 2013, and soon after held a ceremony at an Elvis impersonator “chapel” — if you can call it that — in Las Vegas. So, Chuck and Willow’s wedding had come just a couple of years before detective John Frawley showed up on their doorstep in 2015. Chuck stepped into the room after a moment to meet the detective.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Is, is there somewhere we could talk for a couple minutes—

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Sure.

Dave Cawley: This is the first time you’re hearing Chuck Warren’s actual voice in this podcast. None of his prior interactions with police in this case were recorded.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I’m here to talk to you. I’ve just, I was assigned a case a few months ago. Sheree Warren. What’d happened is, uh, some remains were found in Davis County. I don’t know if you saw that on the news or not.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I didn’t.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Ok … and anytime something like that happens a lot of old cases are kind of re-opened and so the case was assigned to me. I read through it and was wanting to know if I can just talk to you and help me answer some questions and clear some things up. I know that you’d talked to detective Bell, what, that was about 30, not quite 30 years ago but—

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Damn near.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: John said “I know that you had talked to detective Bell not quite 30 years ago.” Chuck replied “damn near.”

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): And so, yeah. Go ahead Charles.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I, (laughs), his notes would probably be the best source.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: In case you didn’t catch that, Chuck said detective Jack Bell’s notes from 30 years earlier would be the best source for his story. Chuck said he’d recently suffered a stroke. It’d impacted his memory.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Sometimes I can remember, uh, things of—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —but, what I said at that time, I, y’know, he’d have it all down, I would think—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —with how good he was at taking his notes. … I used to have a photographic memory where I could remember, I had a phone number—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Right.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Y’know—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Right.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I could remember it forever.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Or even numbers on cars.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Well I’m sorry, sorry to hear that. But I was wondering if, y’know actually reading through that, through that report I, I have, I, I, more questions, actually. I, and so that’s why I, y’know, it’s like “I’ll call Charles and—”

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): “—and maybe talk to him.”

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Well, ask me and I’ll see what—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah. Well, I’d like to, if we could, maybe just go back to, umm, start from, start from the day that, that Sheree disappeared.

Dave Cawley: They went through the child custody arrangement Chuck and Sheree had worked out during the summer of 1985, after they’d separated. Chuck said he’d worked graveyards at the railroad and Sheree’d worked days at the credit union. They’d met each morning to trade custody of their son.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): She would drop him off at Denny’s. We’d have coffee together and she’d go to work.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): ‘Kay.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): And then, the same in the afternoon.

Dave Cawley: Chuck told John he’d worked midnight to 8, and he’d gone to meet Sheree at the Denny’s shortly after that. But Jack Bell’s notes said something different.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): In his report, he says that, umm, you, you and Sheree met at the Denny’s at 7 a.m., around 7 a.m.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Couldn’t have been 7.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Couldn’t have been 7?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): No, I’d be, I worked ‘till 8.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Ok.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I wouldn’t have left an hour early. (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: There were other small inconsistencies between Jack’s notes and what Chuck Warren told detective John Frawley in this interview. Jack’s notes described Chuck taking his and Sheree’s son to breakfast, before dropping the boy off with Chuck’s parents for the day. But Chuck told John he didn’t remember doing that. He thought he’d given the boy to Alice, his first wife.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Then it, it actually says that you and Alice go to lunch.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Uh, that day?

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I don’t remember that, but—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): ‘Kay.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —but we could’ve, I don’t know.

Dave Cawley: John asked what Chuck’d planned to do later that day, on the afternoon of Sheree’s disappearance.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): You had asked her to pick you up at Wagstaff Toyotas, or something like that?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah, yeah.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Ok. Can you tell me more about that?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): (Exhales) Well, I don’t, I never made it down there—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —and I called and told her—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Ok.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —that uh, y’know, I wasn’t going to make it—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): And uh, (pause), but I just never made it down there.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): You never made it down there.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Can you, can you tell me, Charles, how, what changed, what changed your plans. Why didn’t you go to Wagstaff? Do you remember that?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Uh, I was looking at cars, I think and uh, I uh, or something was wrong with my car. I can’t remember. And, umm, I don’t know. [Expletive]. I don’t know.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): ‘Kay.

Dave Cawley: “I can’t remember, I don’t know.” Not a very satisfying answer. Chuck said he’d called Sheree at the credit union sometime around 4, which was consistent with what he’d told detective Jack Bell back in 1985. Chuck told detective John Frawley he couldn’t remember what he’d done after making the call to Sheree. John said according to Jack Bell’s notes, Chuck’d gone for a jog. Chuck said that was right. He’d jogged from his house into downtown Ogden, but the sun’d gone down so he’d stopped.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah, yeah. I was just going to say, do you always run in the dark? (Laughs)

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): No, no. No, it seemed like it got dark and that’s why I went to Denny’s.

Dave Cawley: A different Denny’s, not the Denny’s where he’d picked up his son from Sheree earlier that morning. Chuck said he’d ordered a cup of coffee and called his first wife, Alice, asking her to come pick him up.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Oh ok, that makes, that makes, so you go, you go for a jog and then you’re there at the Denny’s having some coffee and she picks you up.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah, I drank a lot of Denny’s coffee.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): (Laughs) Do you still drink it?

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): He does. Yes, he does.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

Dave Cawley: Chuck Warren’s story left him with a roughly two-hour window on the afternoon of Sheree’s disappearance for which he had no real alibi. He’d told Jack Bell in 1985 he spent those two hours jogging. Just jogging.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): And you actually give your whole jogging route to him.

Dave Cawley: That route took Chuck four miles from his house into the heart of downtown Ogden, then another mile-and-a-half back to that Denny’s restaurant. Chuck hadn’t provided any specific destination for his “jog” back in 1985 and he didn’t volunteer one now, either.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Well I appreciate you talking with me. Umm, like I said, this case, y’know, it’s open. It’s an open case but I, questions come up, y’know and—

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I can’t help you with ‘em.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Oh you did, actually. You helped me quite a bit.

Dave Cawley: Detective John Frawley asked Chuck what he’d done that night, after his jog. Chuck said he’d spent the evening at home with his first wife, Alice.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I went to bed early.

Dave Cawley: “I went to bed early.” But wait, didn’t Chuck work graveyards? John asked about this inconsistency and Chuck became confused. He said he couldn’t remember whether he’d gone to work that night, or if he’d stayed home with Alice.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): That I can’t tell you.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): It’s a long time ago.

Dave Cawley: But Chuck remembered wondering where Sheree was, why she hadn’t come to pick up their son. He said he’d called Sheree’s mom, Mary Sorensen.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): It was before 10 o’clock and after 9:30. That’s all I remember—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Ok, between 9:30 and 10 p.m. You’re—

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —somewhere in there.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —you call Mary and—

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —say “hey, where’s she at?”

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): ‘Kay.

Dave Cawley: This was different from what Chuck had told detective Shane Minor in 1999. Back then, Chuck said Mary’d called him looking for Sheree, not the other way around. And there’s no record in the case files Mary ever mentioned talking to Chuck on the phone that night.

John moved on, to the day after Sheree disappeared. He said according to Jack Bell’s notes, Chuck’d gone to work that day, on the dayshift.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): And you worked for the railroad. What did you do for the railroad?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I was a clerk at that time.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): But this wasn’t like you getting on a train and traveling around—

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): No, no.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —this was you working in an office.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Just right there on 28th.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Ok.

Dave Cawley: Jack Bell’d tried to call Chuck at the rail yard that day. Chuck hadn’t been there. A coworker had reportedly told Jack Chuck’d come in that morning, but left sick a bit before noon. Detective John Frawley asked Chuck if he had, in fact, left work sick that day.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): The only time I took off work is, uh, is uh, when I was going partying. If I was sick, I went to work, y’know?

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): (Laughs) Yeah.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): So, I used my sick leave to go partying, not—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Ok.

Dave Cawley: Chuck didn’t explain what he meant by “partying.” John pressed: why hadn’t Chuck gone to police detective Jack Bell about his missing wife?

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I guess he’d tried to call you. Did he, did he leave messages for you to call him?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I wouldn’t have left work in the middle of the shift.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Ok.

Dave Cawley: But according to Jack’s notes, Chuck’d described leaving work and going into downtown Ogden the day after Sheree disappeared, to more or less the same place he’d gone while out “jogging” the afternoon prior. That seems a bit strange to me. I know from talking to police who worked Ogden in the ‘80s, the area where Chuck said he’d jogged to the evening of Sheree’s disappearance — then returned to the following day — happened to be a hot spot for prostitution.

I bring that up, because while researching Chuck Warren, I learned Salt Lake police cited him for sexual solicitation in April of 1993. That’s a fancy way of saying he got a ticket after being caught in a prostitution bust. The court record doesn’t provide much detail, beyond saying Chuck pleaded guilty and paid a $200 fine. All in all, a pretty petty crime. But embarrassing, the kind of thing a guy might want to keep hidden from a nosy detective.

Now think back to that tip I mentioned several minutes ago: a credit union worker’d told police she’d heard Chuck took a cash advance on the day Sheree disappeared. Why would Chuck have needed cash? This all leads me to wonder if Chuck might’ve met someone while out for that “jog.”

Detective John Frawley needed to pin down as much of Chuck’s timeline as possible, but Chuck said he couldn’t remember anything specific about that day after Sheree disappeared. His wife, Willow, interrupted to ask if any of his old coworkers might remember.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Who’s one of the railroaders that worked with you at that time that would remember when—

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): They’re all dead, honey. (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: No one could say for sure where Chuck Warren was or what he’d done the day after his wife disappeared.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Do you keep any, uh, timecard records from that time? Do you have any records like that?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): No. (Laughs)

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I know, she said you kept everything, so. (Laughs)

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): No, no. Just phones.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I have lots of checkbooks.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): (Laughs)

Dave Cawley: I wasn’t in the room, but I can just imagine detective John Frawley’s face when Chuck Warren’s wife, Willow, said she had Chuck’s old checkbooks. Those were just the kinds of records John wanted.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): How far back do your checkbooks go in the closet?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Uh, I don’t know. I think just the ‘80s.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): (Laughs) That’s the time period honey. Want me to go look for a minute—

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): No, no.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —see if there’s anything?

Dave Cawley: Checkbooks weren’t all Chuck had in his closet. He said he still had his very first cell phone.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): It’s your very first one and you still have it?

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): (Laughs)

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): He, he keeps everything.

Charles Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I saved all of ‘em except the ones that got stolen.

Dave Cawley: “He keeps everything,” Willow said. But Chuck couldn’t remember if he’d had that cell phone in 1985.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Oh, you had a lot of the first ones that came out so you might’ve but—

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —I don’t know.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): What, so you did have a cell phone a long time ago?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I, I did a long time ago but I don’t know whether I had it that time.

Dave Cawley: John didn’t let this go.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Did you have a cell phone in ’85?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I don’t know for sure.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Possibly?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Seems like, I don’t know. I can’t remember what year I actually got it.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Would’ve been one of the first ones coming out, and—

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah, yeah.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —I mean, I remember those big ones.

Dave Cawley: The Motorola DynaTAC was the first commercially-available cell phone. Today, most people just know it as “the brick.” It hit the market in 1983, two years before Sheree disappeared. Chuck said he’d for sure had a cell phone in ’88. But he wasn’t sure about ’85. John Frawley wondered what evidence a digital forensics lab might be able to scrape from a device that primitive, if Chuck Warren had owned one when Sheree disappeared.

I can tell you from my work on the Susan Powell case in Cold season 1, cell phone forensics are a critical tool in many modern investigations. But cell phones of the 1980s are dinosaurs compared to the smartphones of today. The Motorola DynaTAC didn’t have a camera, GPS or SIM card, let alone apps or a web browser. Still, you never know what you might find, unless you look.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Is it the one I still have down the hall?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Might be, yeah.

Dave Cawley: John didn’t tell Chuck he’d already obtained his old bank statements with a search warrant, but he tipped his hand just a bit to ask about something specific.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): You had a financial transaction in Elko, Nevada. In the, in the beginning of, of November.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Financial transaction in Elko?

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Elko, Nevada, yeah.

Dave Cawley: Chuck said he’d started commuting between Ogden and Roseville, California, just outside of Sacramento, at some point after Sheree disappeared. He’d driven I-80 across Nevada every two weeks. Elko sat on that interstate.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Whatever that was in Elko, I probably would’ve stopped there for gas. That was that waypoint, y’know? If you looked every two weeks you’d probably see a receipt there.

Dave Cawley: But he couldn’t say for sure. And Chuck’s own brother has told me this timeline doesn’t match up. He said Chuck was living and working in Roseville, California during the 1970s, not the ‘80s. So what were those transactions in Elko and Reno? I don’t have a good answer. Maybe Chuck’d gone “partying” one month after his estranged wife disappeared.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): When I heard you worked for the railroad, I thought you were like actually traveling from state to state on the railroad. But that’s not what you did?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): No, no, no.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Ok.

Dave Cawley: This seemed to further discredit the theory Chuck might’ve used his railroad access to hitch an untraceable ride home from Las Vegas after dumping Sheree’s car there. But Chuck hadn’t managed to allay many of detective John Frawley’s other suspicions. And he certainly hadn’t cleared himself as a suspect. To the contrary, his actions on the day of Sheree’s disappearance and the day after remained questionable.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Hey Charles, is it ok if I come by and talk to you or call you again if I have any questions?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Is that alright? I do appreciate your time and talking with me.

Dave Cawley: Chuck apologized for his faulty memory and again said he believed Jack Bell’s notes were the best source for his story. John tossed another question at Chuck, almost as an aside.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): How do you know Cary Hartmann?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I don’t.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Oh, ok. (Laughs)

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I’ve never seen him before—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Ok.

Dave Cawley: Chuck said detective Jack Bell had dropped by to talk to him once, after Cary’s arrest in the rape case. Jack’d reportedly told Chuck how Cary’d come in a week or so after Sheree disappeared. At that time, Cary’d described a coworker of his having a psychic dream.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): He had a dream that she’s up in the mountain?

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Yeah, yeah. That they’d find her up there. You ought to, if he didn’t put it in there, then—

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): ‘Kay.

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): —I don’t think I dreamed that up.

John Frawley (from June 23, 2015 police recording): (Laughs)

Chuck Warren (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I remember him telling me that, though. ‘Cause I remember that something about Cary, uh, him or his buddy had a vision of something.

Dave Cawley: Enough. Chuck was just regurgitating the same stories we’ve heard before: Cary’s coworker had a dream about Sheree’s death, an anonymous psychic sent KSL a letter about it. Only now, it’d gone a few steps through the rumor mill and was being fed back into the investigation. This how misinformation poisons investigations. Detective John Frawley wasn’t going for it.

John Frawley: Could be great information, could be very interesting but does it get us to our goal?

Dave Cawley: John did not intend to entertain psychics and seances.

John Frawley: We’re gonna stick to the evidence and what we can absolutely say we know and filter everything else out.

Dave Cawley: Jack Bell, the original investigator on the Sheree Warren case, had tried to put the screws to his lead suspect — Chuck Warren — working the human angle.

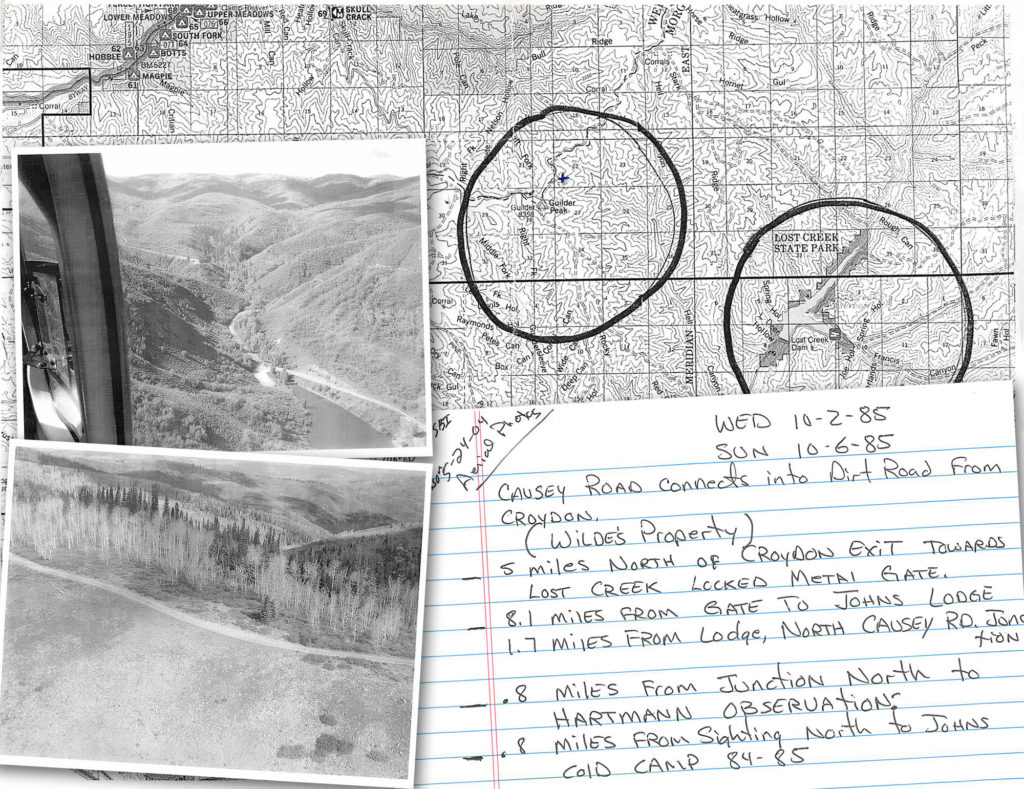

Shane Minor, the former Ogden cop who’d taken up the Sheree Warren cold case in 1998, had focused on trying to find her remains on the mountain where the second suspect — Cary Hartmann — might’ve dumped her.

John Frawley brought a new approach. He wanted to prove the case by the record: show who had motive, means and opportunity.

John Frawley: Really, uh, dissect the involved parties’ stories.

Dave Cawley: And John suspected there was more to Chuck Warren’s story than Chuck was willing to admit.

[Ad break]

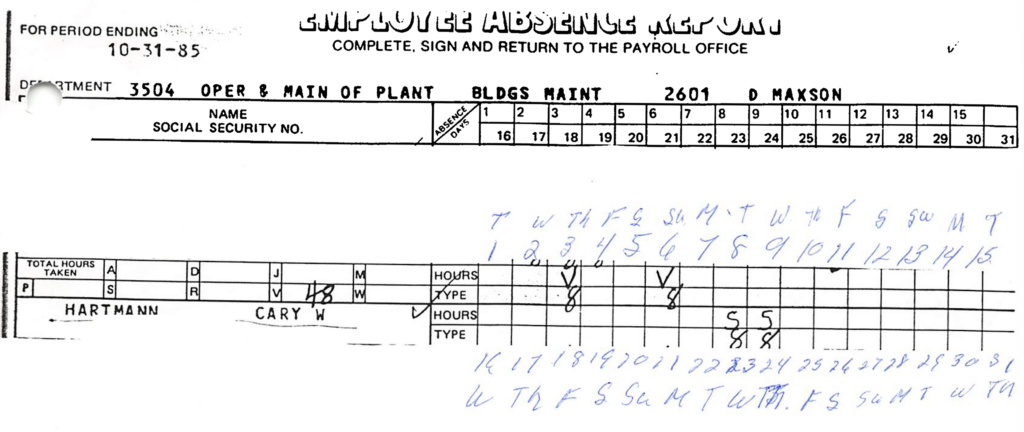

Dave Cawley: Roy City police detective John Frawley had found several inconsistencies with Chuck Warren’s story about the disappearance of his ex-wife, Sheree Warren. John wanted Chuck’s old timecards, to see if they might shed light on where Chuck was the day Sheree turned up missing.

John Frawley: That was, that was difficult.

Dave Cawley: The railroad Chuck’d worked for, Southern Pacific, had merged with Union Pacific in the mid-‘90s. By 2015, the old railroad’s daily employee records were long gone.

John Frawley: There’s things that we couldn’t get that were lost like uh, persons of interest, their, their timecards. Y’know, things like, y’know were they at work?

Dave Cawley: Chuck’s timecards might’ve revealed whether he’d gone to work at all the morning after Sheree vanished. Without them, John could only wonder.

John Frawley: You’re really behind.

Dave Cawley: If Chuck’d gone to work on the dayshift that morning, as he’d originally told police in 1985, he would’ve started around 8 a.m. In a past episode, we did our math homework, the story problem about how much time it would’ve taken to get Sheree’s car to Las Vegas on the night of her disappearance, then return home to Utah. Making to Ogden by 8 a.m. would’ve been nearly impossible. But we can’t say for sure if Chuck did or didn’t go to work that day without his timecard.

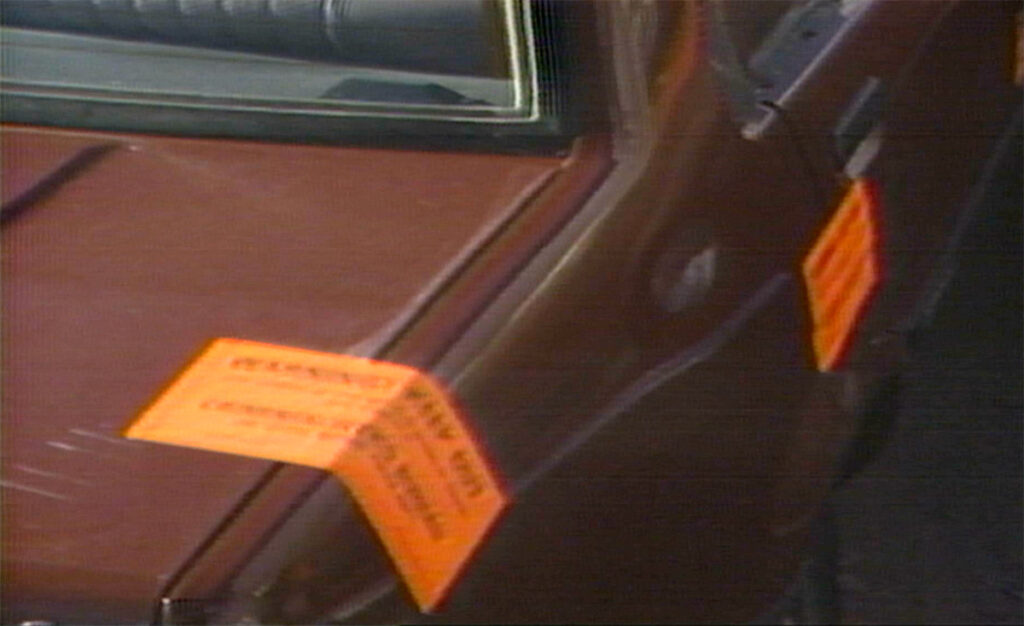

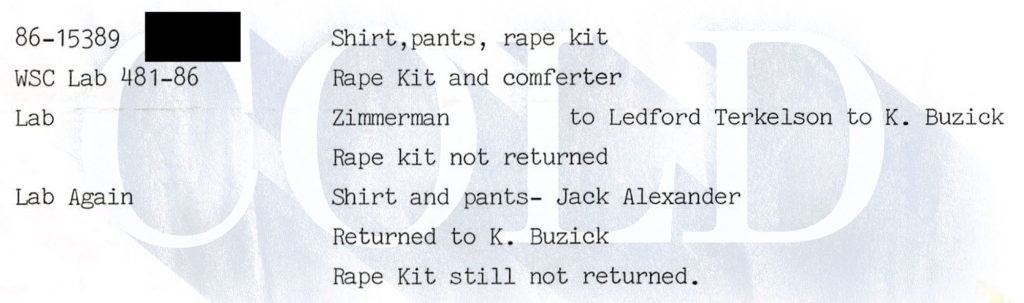

John Frawley: Her car is found at the Aladdin Hotel and Casino on November 11th and, uh, it’s processed by Las Vegas police.

Dave Cawley: “Processed” means scouring the car for evidence. Today, forensic technicians would vacuum the car for hair or fibers, use chemical reagents to look for blood, check for fingerprints or maybe even use a cadaver dog to sniff for a whiff of human decomposition. Collecting DNA evidence wasn’t yet standard practice in 1985. The Las Vegas police records I’ve obtained only mentioned searching for fingerprints.

John Frawley: There is a print on the window and they collect that print.

Dave Cawley: The Las Vegas police records say it appeared the print came from a woman. But they’d never linked them to anyone specific. In fact, detective Jack Bell had never seen those prints.

John Frawley: Because like I said, my bosses didn’t want me to go down there.

Dave Cawley: Jack’d tried to find a copy of Sheree’s fingerprints to compare against way back then, but had come up empty.

Jack Bell: Y’know, I got a lot of faith in Las Vegas’ PD.

Dave Cawley: It’s baffling to me police didn’t show more interest in Sheree’s car at the time.

Jack Bell: There’s paperwork in one of the reports of what they found.

Dave Cawley: In an alternate universe, Jack would’ve written a search warrant for the car, then had a wrecker haul it back from Las Vegas. Sheree’s car would’ve ended up in evidence and crime scene technicians here would’ve torn it apart. Who knows what they might’ve found. Maybe they would’ve kept the car all these years, giving John Frawley an opportunity to examine it again today, with better techniques and technology. Instead, the car just sat in a Las Vegas impound lot.

John Frawley: And then the car is later given back to Charles Warren.

Dave Cawley: Records show Chuck picked the car up on Christmas Eve of 1985. Six months later, he’d traded it in to a dealer. John wanted to know where Sheree’s car had gone from there. He ran the car’s VIN number and was able to follow it for a few years before losing the trail.

John Frawley: We tried to track it down and it’s long gone.

Dave Cawley: Whatever secrets Sheree’s car might’ve held, they’re lost to us now.

John talked to Chuck and Sheree’s son, Adam, in October of 2015. Adam remembered his dad visiting casinos in Reno when he was a kid. Adam also specifically recalled going to Las Vegas one time with Chuck, when he was about seven years old.

John Frawley: And he told me that the Aladdin Casino was a place that his father frequented.

Dave Cawley: The trip Adam described would’ve happened in 1989, four years after Sheree disappeared.

John Frawley: And Adam actually remembered his father taking him there on a vacation to the Aladdin.

Dave Cawley: Why would Chuck Warren have taken his and Sheree’s son to the Aladdin, of all places?

John Frawley: So I found that significant.

Dave Cawley: John kept thinking about those old checkbooks squirreled away in Chuck Warren’s closet: decades of financial documents that might reveal where Chuck’d gone, and when, in the fall of 1985. He again went to talk to his chief, Carl Merino.

Carl Merino: We found out that there were a lot of mistakes made early in the investigation.

Dave Cawley: Carl told me, in his experience, cops often resist sharing information with the public, victims, witnesses and even with other officers. And there can be good reason for that. Giving out too much info can tip off suspects or taint an investigation.

Carl Merino: It’s a balancing act. You’ve got to know what you can release.

Dave Cawley: But Carl told me “police egos” sometimes cause investigators to be overprotective. That can lead to turf battles that stymie investigations.

Carl Merino: When you’re trying to solve crimes, it’s not a competition. Except between law enforcement and whoever committed the crime.

Dave Cawley: Carl believed jurisdictional squabbles were part of what’d gone wrong with the Sheree Warren case. There wasn’t a big, flashing neon sign saying “murder” with an arrow pointing to a body in Salt Lake, where Sheree’d last been seen. So, the Salt Lake City police department had declined to put much effort into what it viewed as a Roy City missing persons case.

Carl Merino: I think there should’ve been more pressure put on Salt Lake to, to help with it. I have no idea even what evidence might have been collected there.

Dave Cawley: There are no witness statements in any of the Sheree Warren case files from employees at Wagstaff Toyota, where Sheree’d planned to meet Chuck on the afternoon of her disappearance. Likewise with patrons of the bar where Cary Hartmann supposedly spent that evening. No one identified or questioned them. The dealership was in Salt Lake City. The bar was in Ogden. The Salt Lake and Ogden police departments could’ve helped the much smaller Roy police department by gathering those statements.

Carl Merino: There were opportunities for evidence gathering.

Dave Cawley: But both Salt Lake and Ogden had at first wiped their hands of the Sheree Warren case. It wasn’t their problem. Carl agreed with his detective, John Frawley: they needed to chase the evidence. And they now knew at least some of that potential evidence was sitting in Chuck Warren’s closet. With his chief’s blessing, John wrote up another search warrant. This time, he asked a judge for permission to go into Chuck’s home, the same house Sheree’d once lived in, and hunt for any financial records from 1985. John also wanted Chuck’s old cell phones.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): Those phones down there, the phones there, the old radios they used at the railroad, the two-way radios.

Dave Cawley: Chuck’s wife, Willow, had told John she and Chuck kept everything, including his old cell phones, amid all her clutter in the basement.

Willow Hendricks (from June 23, 2015 police recording): I thought that’s where we had the brick phones too but it’s not. I know I’ve seen ‘em down, probably in your other closet.

Dave Cawley: John served the warrant on December 14th, 2015. He and others from the Roy Police Department scoured Chuck’s house, taking five checkbooks, a pile of floppy disks, bank statements, mortgage papers and more. But they didn’t find any old cell phones. Where those had gone, I can’t say. I also don’t know what Roy police learned from looking through all of Chuck’s old financial papers. Chief Carl Merino told me that evidence has to remain private.

Carl Merino: You’re right. You do have to keep certain things back.

Dave Cawley: What I can tell you is the search warrant didn’t lead to an arrest. Nothing police found provided probable cause to book Chuck Warren into jail for his ex-wife’s presumed murder. Detective John Frawley was learning just how crushing the Sheree Warren case could be.

Carl Merino: And then detective Frawley got transferred to undercover narcotics.

Dave Cawley: Frawley’d had Sheree’s case for about a year. He’d done more than anyone else had in a decade. And he’d only just started getting some momentum, when he’d had to turn away.

John Frawley: Yeah. It is tough because your day-to-day caseload doesn’t stop.

Dave Cawley: John handed the box of Sheree Warren case files back to chief Carl Merino.

Carl Merino: The box would get passed and it just kept getting overlooked and so the case moved on to another detective, Ryan Reid. And he worked it some but he was, y’know, it was, again, he had all of his other duties and so it didn’t get worked a lot.

Dave Cawley: The Sheree Warren case lapsed into inactivity once again. For Carl Merino, it felt like going back on a promise.

Carl Merino: It’s not ideal, but for a smaller department, you can’t task somebody with just working an old case like that. You just don’t have the staffing to do that.

Dave Cawley: Former Ogden City detective Shane Minor had himself spent years driven to find answers about what’d happened to Sheree Warren. He’d picked up that torch in 1998. But his flame had sputtered in 2006, after a series of setbacks.

Shane Minor: Like I said a lot of stuff I did on this case was when I had time to work on it and—

Dave Cawley (to Shane Minor): And that time got more and more precious?

Shane Minor: Right.

Dave Cawley: Shane’d documented all his contacts, building a list of potential witnesses. He’d kept notes, newspaper clippings and all sorts of other records. And he’d compiled a 30-plus page summary of the case, making it ready for any future investigator who might one day take over.

Shane Minor: It’s who’s gonna pick up that case on the shelf and start looking into it, because of the time that’s involved and costs that could be involved, so.

Dave Cawley: By the time the remains of Teresa Greaves emerged on a hillside in 2015, Shane was deep in preparation for a capital murder trial.

Shane Minor: There’s a couple other cases I was involved with that was very demanding.

Dave Cawley: One of them was the case we covered in Cold season 2, the disappearance of Joyce Yost. At the start of 2015, Doug Lovell, the man who’d killed Joyce, was asking a Weber County jury to take him off death row. Shane had spent months working with prosecutors, helping them prepare for Lovell’s trial. The Joyce Yost case consumed Shane’s time and attention, so he didn’t take part in Roy City’s renewed Sheree Warren investigation in 2015, though he was aware of it.

Shane Minor: They did pick it up and assign a detective to start doing some stuff on it.

Dave Cawley: “Doing some stuff like” interviewing Chuck Warren.

Shane Minor: They were just kind of reiterating, re-doing the same stuff that had been done.

Dave Cawley: And getting nowhere. Then, Roy detective John Frawley moved into undercover narcotics. As I said, the investigation went dormant for two years. John returned from his undercover assignment with a renewed desire to close the Sheree Warren case.

John Frawley: What our goal and what we’re driven for is to get the family some answers, y’know?

Dave Cawley: So, in February of 2018, he invited Shane Minor to come brief the Roy City Police Department about his work on the case.

Shane Minor: Yeah, I took it over to them and I’m like “y’know, I’m done” and I felt uncomfortable about (sighs) just looking for that one piece.

Dave Cawley: John Frawley’d operated under the assumption Chuck Warren was his prime suspect, and for good reason. That’s the conclusion most people would draw by reading Jack Bell’s old case notes. The notes do mention Cary Hartmann, first as a witness and then later as a serial rapist, but Jack’s notes don’t give the impression Cary had any motive to murder Sheree. Shane Minor had learned a lot more about Cary during his years working the case. Shane told John about Cary’s ties to the Ogden Police Department.

John Frawley: He’s a reserve police officer, y’know, he understands police work more than your typical person.

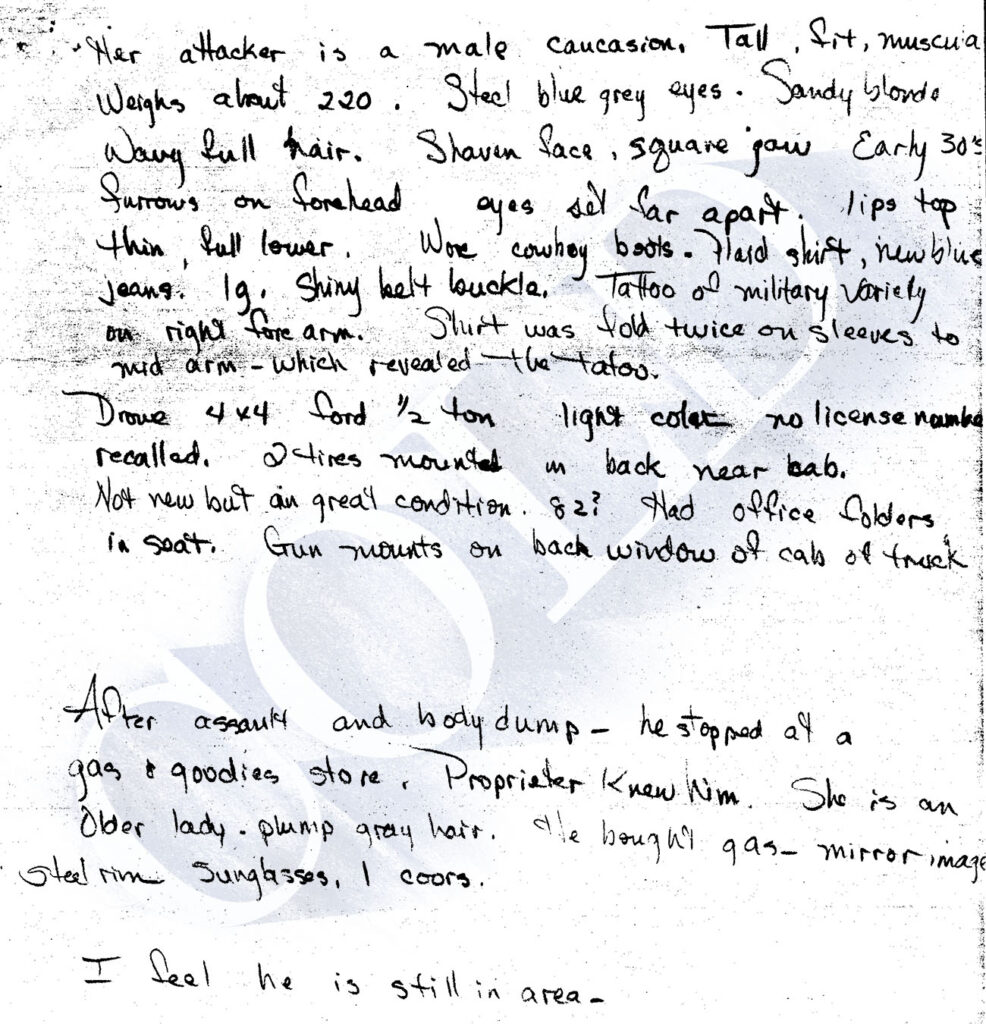

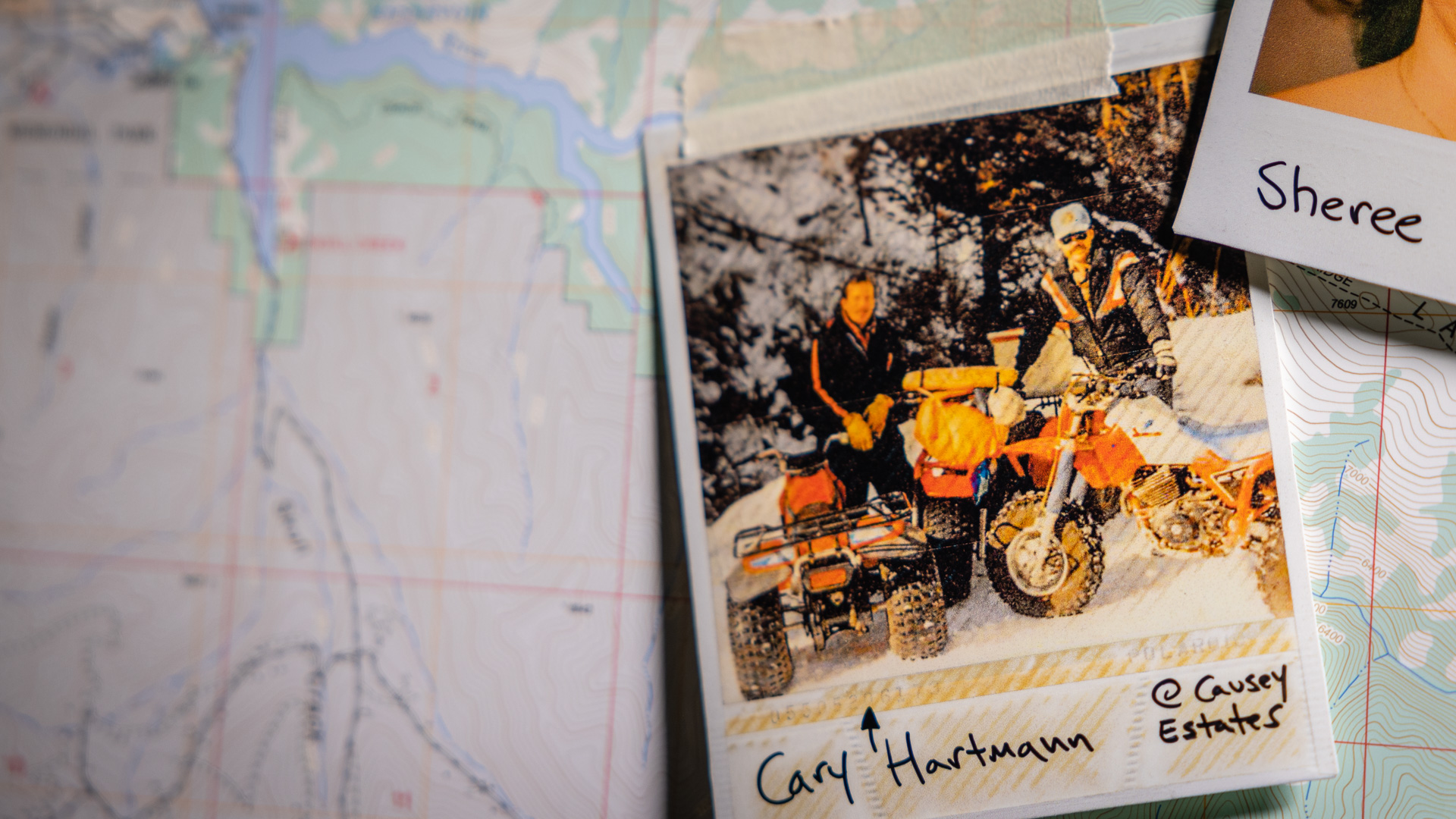

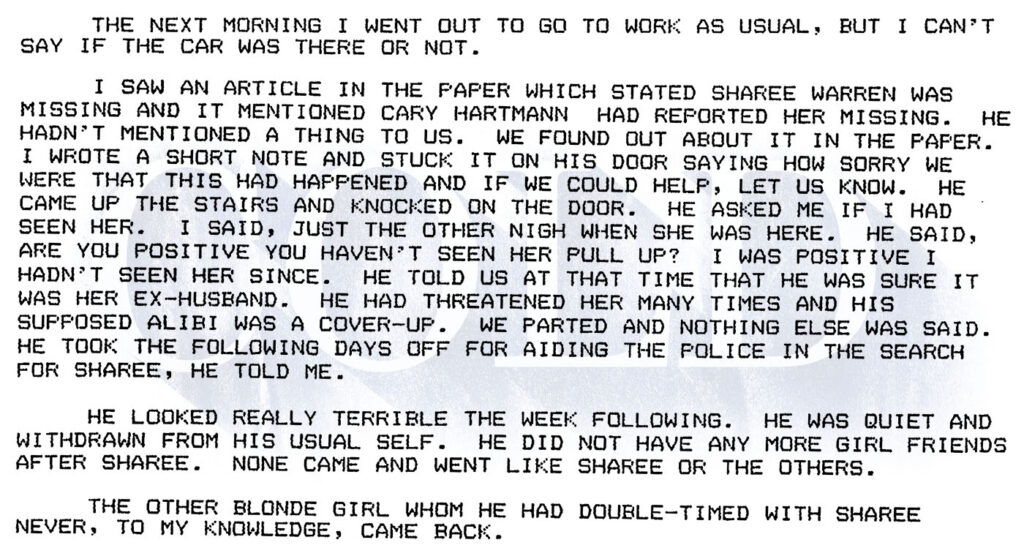

Dave Cawley: Shane told John about the two women who’d lived above Cary at the time of Sheree’s disappearance, who’d reported Sheree coming to their house one night in early October, 1985.

John Frawley: They heard her voice, they knew her voice. They saw her car outside, they knew her car.

Dave Cawley: Shane told John about how Cary’d met up with his TV reporter friend Larry Lewis a few days later.

John Frawley: They were actually riding 3-wheelers up in the foothills.

Dave Cawley: And Shane said just one day after that, the elk hunting guide Fred Johns had seen Cary and another man on the mountain behind Causey Reservoir.

John Frawley: Fred Johns was positive that this was Cary Hartmann. He knew him.

Dave Cawley: Shane told John he’d confirmed Cary knew his way around that mountain.

John Frawley: It was private land but he had a key from a friend, he had access to that area.

Dave Cawley: The same general area where an anonymous caller had in 1987 told police he’d stumbled across a body…

Anonymous caller (from April 3, 1987 police recording): I’m reporting a body that I found.

John Frawley: He described this, this decomposing body, uh, with a purse next to it.

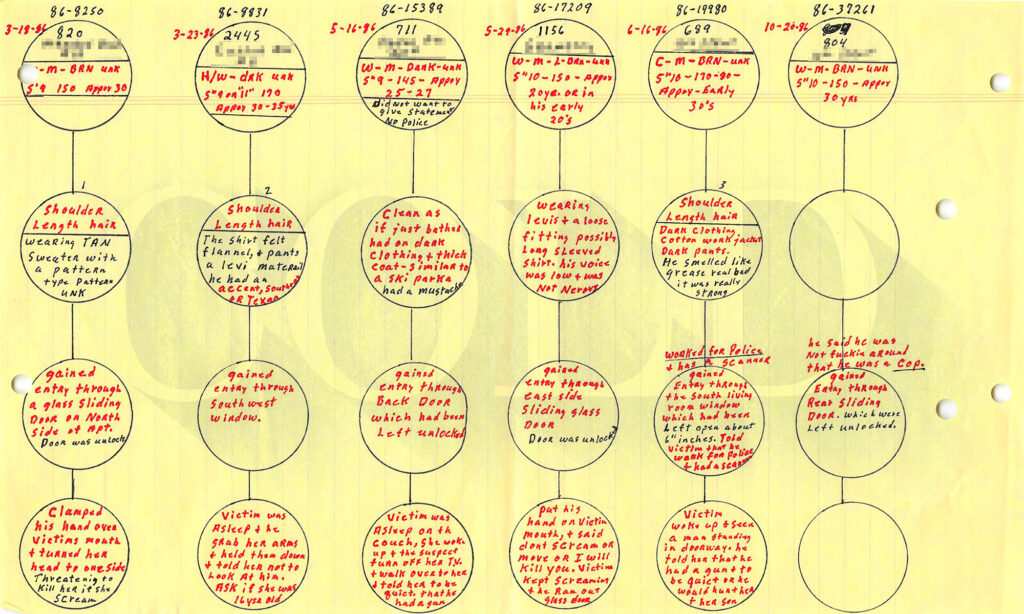

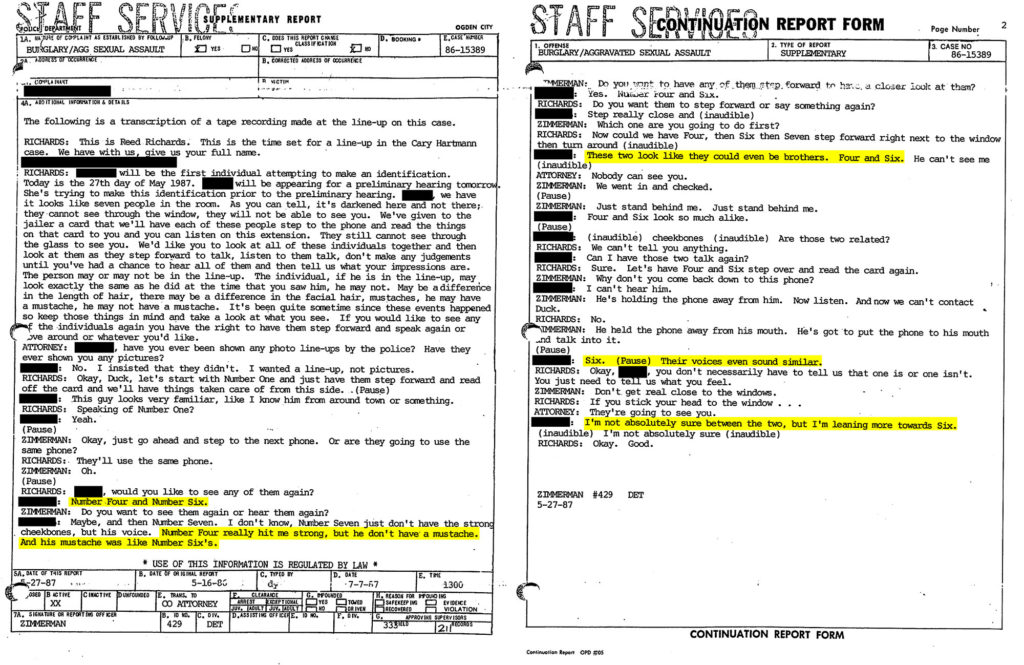

Dave Cawley: …human remains which had still not been found. Shane told John about how he’d served a pair of search warrants at Cary’s apartment, after Cary became the key suspect in the Ogden City Rapist investigation.

John Frawley: A gray leather suede jacket was found and placed into evidence at the Ogden Police Department.

Dave Cawley: Shane told John how, years later, he’d pulled that gray suede jacket out of evidence and showed it to Sheree’s mom, Mary Sorensen.

John Frawley: And Mary identified that jacket as to what she was wearing on October 2nd when she went to work.

Dave Cawley: Or at least, that’s what Mary thought Sheree might’ve worn that day. There’s some ambiguity on this point.

John Frawley: And that jacket was located in Cary Hartmann’s closet.

Dave Cawley: John was coming to understand the potential significance of the gray jacket. If it’s what Sheree left the house wearing on the morning of her disappearance, it couldn’t have ended up in Cary’s possession, unless Cary and Sheree had met at some point later that day.

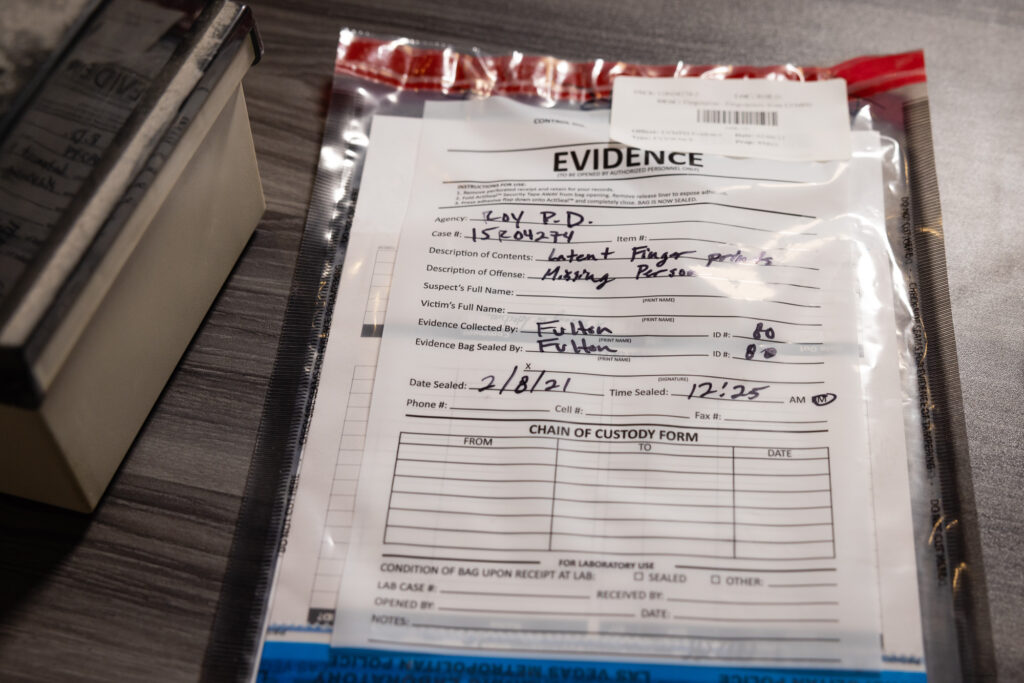

Shane Minor passed the baton of the Sheree Warren case over to John Frawley. That meant Roy police assumed custody of the gray suede jacket. I told John I wanted to see it for myself, hoping I might be able to match it an old family photograph of Sheree. I could only do that if I knew what it was I was looking for.

It’s September of 2022 and I’m in the basement of Roy City police headquarters. I follow an evidence technician named Chelsea Scott through a locked door…

(Sound of key in door lock)

Dave Cawley: …into a small room. It stinks of marijuana. Metal shelving lines the walls. Chelsea points to a box on the top of the shelf in the back of the room. It says Office Depot on the lid.

Chelsea Scott: This contains the jacket.

Dave Cawley: The jacket police seized from Cary Hartmann’s apartment way back in 1987. Chelsea points to another, smaller box on the next shelf down.

Chelsea Scott: We have miscellaneous items here, we have fingerprints from the vehicle that was located, her vehicle that was located in Las Vegas.

Dave Cawley: And I can see a plastic case containing floppy disks off to the side, which I suspect came out of Chuck Warren’s house.

Chelsea Scott: I can bring this up. Anything you want me to bring up I’m happy to. Then you can get like, different shots.

Dave Cawley: Oh yeah, I’m carrying a still camera. And I’m accompanied by a TV videographer. Chelsea carries the boxes out of the evidence room and sets them on a conference table. Detective John Frawley’s there, and I invade his personal space while clipping a small microphone to his shirt collar.

Dave Cawley (to John Frawley): John excuse my uh—

John Frawley: No, go for it.

Dave Cawley: —familiarity here.

John Frawley: Uh, yeah. Not a problem.

Dave Cawley: John sits down in front of the Office Depot box, which is sealed by red plastic tape printed with the word “evidence” in black letters. John tears open the box…

(Sound of tape tearing and cardboard rustling)

Dave Cawley: …then pulls a brown paper bag out of it. I can see numbers written in red and black marker on the bag. I recognize them. They’re the Ogden police department’s case numbers for one of Cary Hartmann’s rapes and the Sheree Warren homicide. The words “coat” and “test fire bullets” are written on the bag as well, along with a barcode label from the Utah State Crime Lab. John pulls another item from the box.

John Frawley: So this was the hangar that the jacket was on.

Dave Cawley: Then, he opens the paper bag…

(Sound of paper bag opening)

Dave Cawley: …and removes the jacket. He sets it on the table, and I lean in for a closer look.

Dave Cawley (to John Frawley): That is not a men’s jacket.

John Frawley: No, it is not.

Dave Cawley: My first impression: the jacket’s smaller than I’d expected. It has a crop body and pinches in a bit toward the waist. There’s a tag on the inside that says 8. It’s on the smaller side of medium.

John Frawley: Yeah this, this is not gonna, in my opinion, not gonna fit a, even a medium-build man, let alone a larger-build man.

Dave Cawley: The jacket has a stand-up collar and ruffles that run vertically over each shoulder, a decidedly feminine touch. There are five buttonholes down the lapel, but only four buttons on the opposite side: the button that should be second-from-the-top is missing.

The suede leather fabric is colored a medium gray. It’s a neutral color that makes the jacket versatile. It would’ve coordinated well with a variety of outfits. But now, it’s crumpled, having spent decades wadded up in a bag. At some point, someone’s used a Sharpie to make markings on the inside of the jacket, toward the bottom of the front flap. John tells me he thinks it’s from when Ogden police sent the jacket to the crime lab 22 years ago.

John Frawley: And it was tested for any evidence of blood or hair or any sort of fibers that could be found on it.

Dave Cawley: We heard about that in episode 6. The crime lab hadn’t found anything.

John Frawley: Based on the technology of that time and, uh, that’s correct. It didn’t yield any results.

Dave Cawley: But I also know John recently re-submitted the jacket for another round of testing.

John Frawley: Yeah, I mean it’s 22 years, y’know?

Dave Cawley: He doesn’t tell me what, if anything, was different this time around. I’ve now gone back and looked at every photo I have of Sheree. There aren’t many, and the gray suede jacket’s not in any of them, but it does fit her style. It strikes me as perfectly plausible Sheree Warren might’ve worn that jacket to work on the morning of October 2nd, 1985.

John Frawley: But the whole hang up is that, Mary’s the only one that can say.

Dave Cawley: Again, Sheree’s mom, Mary Sorensen, told police she thought it was the jacket her daughter left the house wearing on the day of her disappearance. If that’s true, the jacket is evidence that potentially puts Sheree and Cary Hartmann together after Sheree was last seen. Mary’s since died. Police asked Sheree’s dad, Ed, and sister Marcie about the jacket.

John Frawley: Nobody can say whether she was wearing that or not. So the only person that could is now deceased.

Dave Cawley: Maybe not the only person. There’s one other who might know if Sheree was wearing it on that day. His name is Cary Hartmann. Detective John Frawley needed to pose this question to Cary. But Cary hadn’t said a word to police about Sheree Warren since 2005. And Cary had no incentive to talk to Frawley now.

John’d found himself mired in the middle of the Sheree Warren mystery, like all of us are now. He’d walked past Sheree’s picture in the police department lobby hundreds of times without giving it a thought. That’d changed once he’d looked inside the box.

John Frawley: It’s not just a picture in the lobby. It makes it very real.

Dave Cawley: Cary Hartmann had gone to prison at the end of 1987 on a sentence of 15-years-to-life. The prosecutor who’d put him there had expected Cary would only serve the minimum: 15 years. But as we’ve heard this season, Cary’s own unwillingness to take responsibility for what’d done resulted in a much longer stay.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): How long have you done in prison?

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): 32 years, sir.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): And how old are you?

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): I’m 72.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): Yeah, y’know you’ve thrown away a big chunk of your life. Just, I mean it’s just, it is sad.

Dave Cawley: This comes from a recording of Cary Hartmann’s hearing before the Utah Board of Pardons and Parole, on October 29th, 2019. If I had to describe Cary’s first trip before the board in 1992, I’d say “Cary, Cary, quite contrary.” You heard it yourself back in episode 6.

Cary Hartmann (from January 17, 1992 parole board recording): Cary Hartmann didn’t do it. There’s no way on this Earth.

Dave Cawley: But 27 years and a few more rejections from the Board had taught Cary how to speak to those who held his freedom in their hands, like parole board member Bradley Rich.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): Why do you think you were in here as long as you have been?

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): My choices.

Dave Cawley: Cary had learned to swap contrary for contrite.

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): It was a blessing to come to prison, sir.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): Yeah.

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): I deserved what I got.

Dave Cawley: Bradley, the parole board member, asked Cary what’d been happening in his life prior to his arrest, all those years ago. What had led him to break into women’s homes, to threaten to kill their children and to sexually assault them?

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): I operated on thinking distortions that, that were troublesome.

Dave Cawley: Troublesome thinking distortions. How wonderfully vague.

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): When I can’t sort out these distorted thinking errors, which I have learned to do at this point. I’ve worked really hard throughout these many years to correct those distorted thinking errors.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): Mmhmm.

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): I met my needs in unhealthy ways.

Dave Cawley: Like, he said, by impulse spending. Bradley said that answer didn’t quite hit the mark.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): You had, to my way of thinking, a very peculiar and dangerous response to stress. I mean, others might go out and get drunk or revert to the use of drugs or, y’know, binge spend or whatever it is. Y’know, go through a gallon of ice cream. Uh, you chose to violently rape under stress. And, and, and so I’m, I’m trying to make heads or tails of that.

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): Those were, those were parts of my life that were surrounded by pornography in those days.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): Mmhmm.

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): I described that as my drug of choice. When I, when I felt lowly and had no self-esteem, when my life was falling apart, I turned to pornography and masturbation. That led to cruising for women and choosing women to make victims.

Dave Cawley: Low self-esteem led to pornography, which then led to rape.

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): I wish to be defined as who I am now and not who I was. I’m a different man now than I was 40 years ago.

Dave Cawley: Cary’d lived nearly half his life in custody.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): As much sympathy as I feel for your victims, at the same time you’ve made yourself a victim as well and you’ve paid a heavy price for it.

Dave Cawley: But had he paid in full? That was up to the parole board to decide. Bradley went over the latest memo from Cary’s sex offender therapist. It said if paroled, Cary stood about a one-in-10 chance of committing a new sex offense, a three-in-10 chance of carrying out a violent crime, and a five-in-10 chance of committing any crime. In other words, 50-50 Cary would do something that might land him back in prison.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): And that makes you a, still kind of a, of a risk.

Dave Cawley: But, on the other hand, Cary’d obtained a new, more favorable treatment memo just a few months earlier. He handed it over to Bradley.

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): Treatment summary, Justin Clark. Right there.

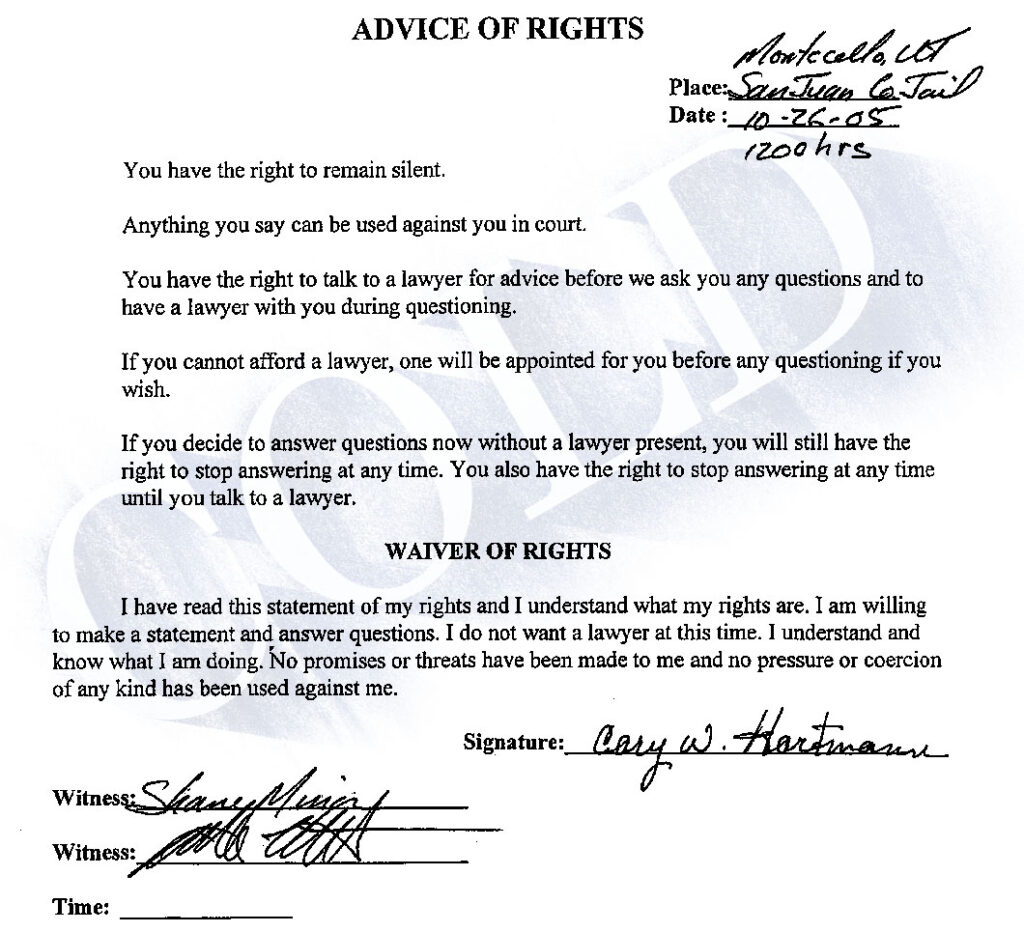

Dave Cawley: Sure enough, the updated report said Cary now presented a below-average risk to re-offend. The parole board had repeatedly teased Cary with a promise of release. But to earn it, he’d had to admit to rape. The board’d cajoled him into taking part in a police interview about Sheree Warren. And the board demanded Cary make several trips through sex offender therapy. Cary’d complied and now, the parole board seemed mollified.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): You’re going to get an opportunity to succeed or fail — my prediction — umm, in the not-too-distant-future.

Dave Cawley: No more fake-outs, no more demands: the parole board had nothing left to ask of Cary.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): Then all we can do is, is, is wish you the best. You have done a big chunk of your life, 32 years, in here. And uh, you’re not a young man.

Dave Cawley: Can you see where this is heading?

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): I wish you well and like I say, with or without a further hearing I think you’re going to get an opportunity. And then we’ll see if you’ve acquired the skills you need to stay out of trouble.

Cary Hartmann (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): Thank you so much.

Bradley Rich (from October 29, 2019 parole board recording): Alright.

Dave Cawley: Cary Hartmann left prison in March of 2020. His release escaped public notice, due to Covid-19 pandemic that was sweeping the globe. Cary quietly headed back to Ogden, to the same community he’d terrorized three decades before.