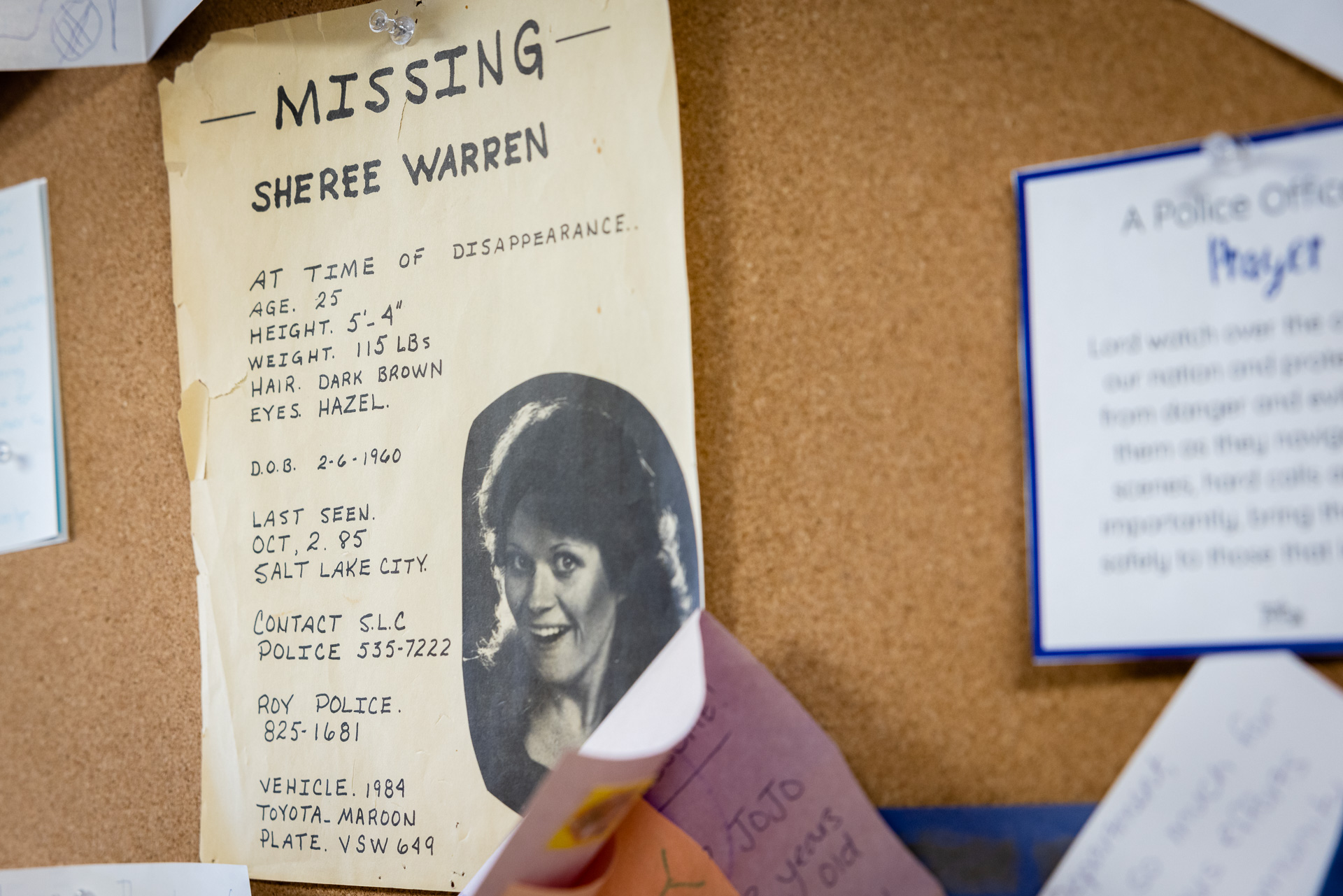

The search for Sheree Warren had sat cold for nearly a decade. But an unexpected discovery reignited the investigation at the start of 2015. A man walking his dog along a busy Utah highway spotted a human skull in a patch of oak brush.

Deputies from the Davis County Sheriff’s Office responded to the site and soon located a shallow grave at the top of a nearby hill. From it, they recovered the skeletal remains of an unidentified woman.

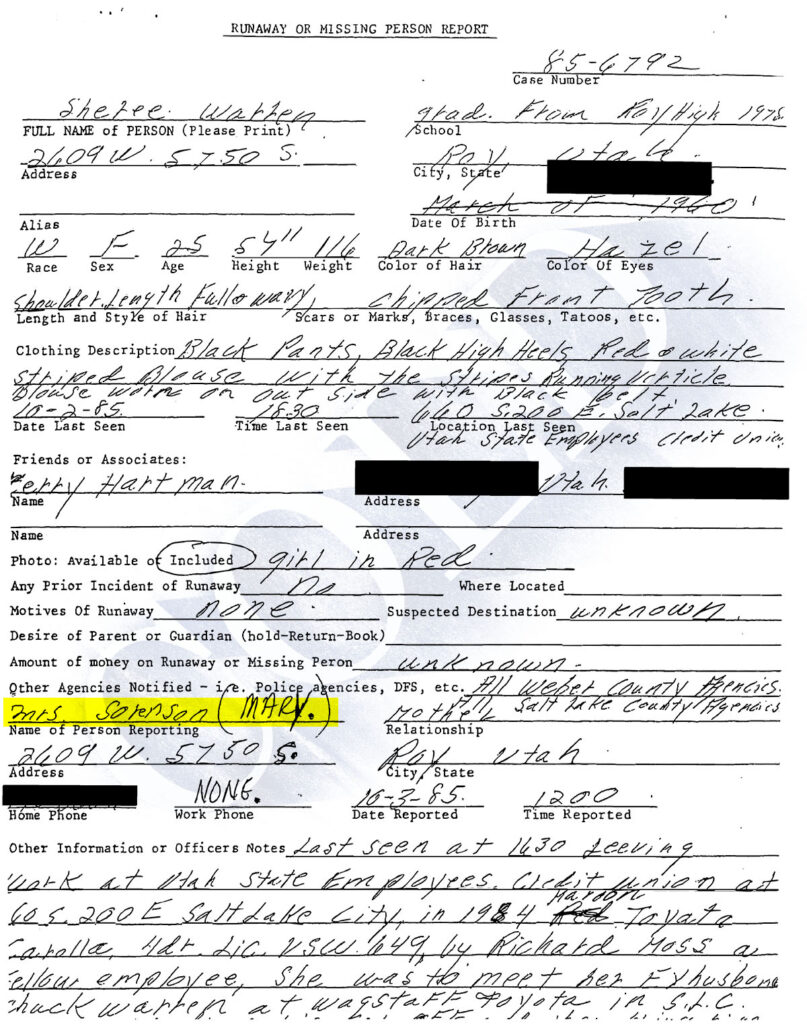

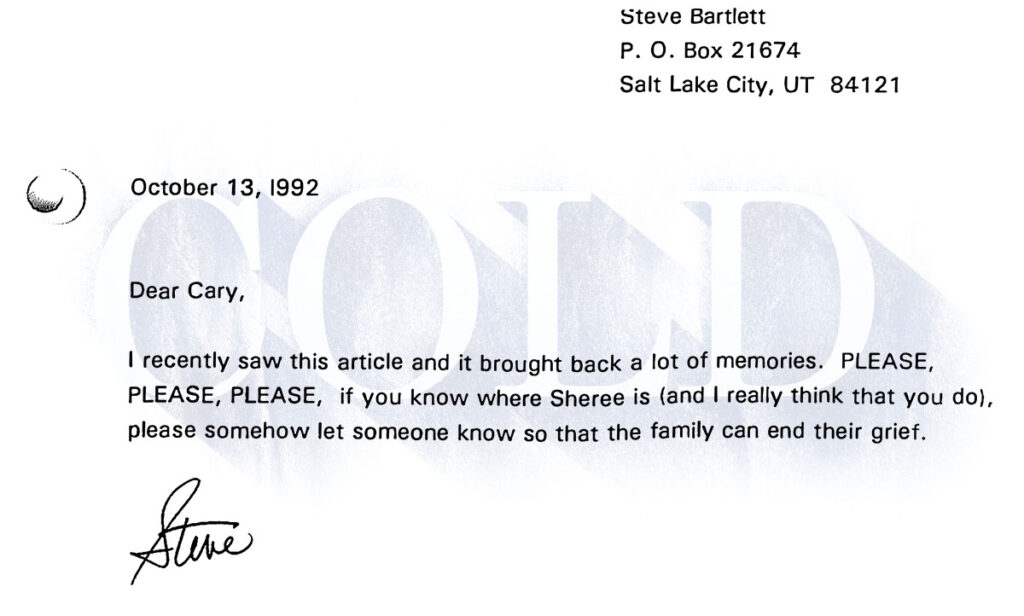

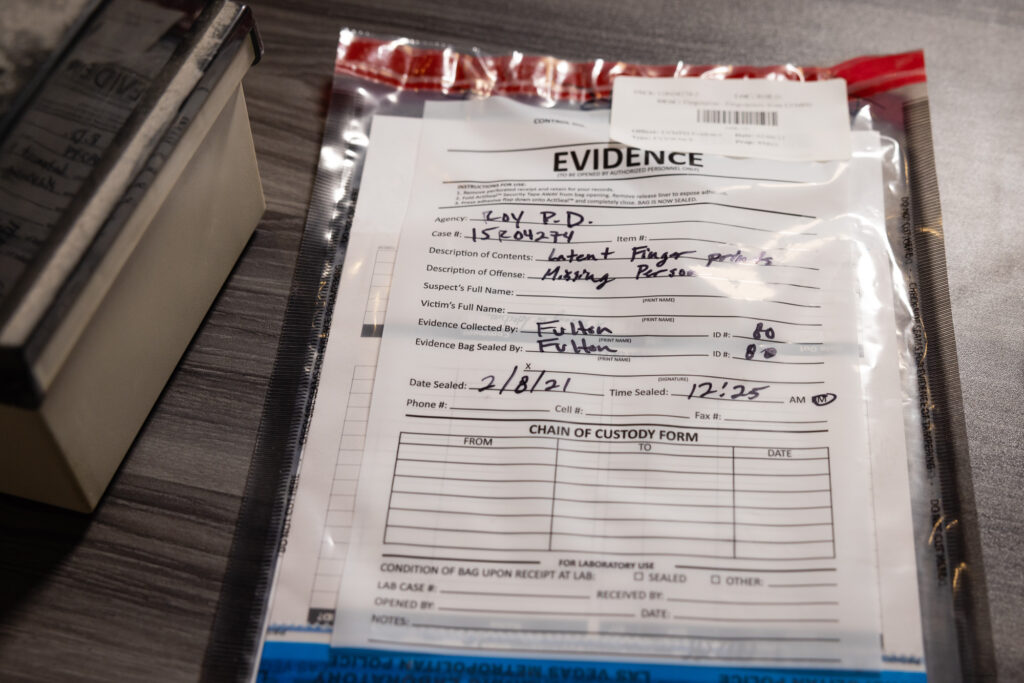

The discovery led to police across northern Utah reviewing their cold case files, looking to see if the Jane Doe might be one of their missing people. A detective in the city of Roy named John Frawley did the same. He took a dusty box of Sheree Warren case files off a shelf and began to read.

“I just became fascinated with it,” John Frawley said in an interview for COLD. “I felt like there was more I could do on it.”

John met with Sheree’s family to collect DNA for comparison purposes. He learned Sheree’s mom, Mary Sorensen, had died just shy of two years earlier.

“What we’re driven for is to get the family some answers,” John said.

Remains identified

Detective John Frawley only had the Sheree Warren case for a few weeks before the Utah Bureau of Forensic Services obtained a dental record match on the unidentified remains. The bones did not belong to Sheree Warren.

Instead, the remains located alongside U.S. Highway 89 were those of Theresa Greaves. Like Sheree, Theresa had disappeared in the 1980s. Police had long suspected she’d been murdered, but no suspects were ever identified.

For Roy police and the Sheree Warren investigation, the news came as another in a long line of setbacks. John’s supervisor told him he could return the box of old case files to the records department. But John wasn’t ready to give up on the case and soon discovered he had an ally.

In March of 2015, Roy City hired Carl Merino to serve as chief of police. Merino told his detective to forge ahead with the Sheree Warren investigation.

“That’s what I wanted to do,” John said.

Interviewing Sheree Warren’s ex-husband

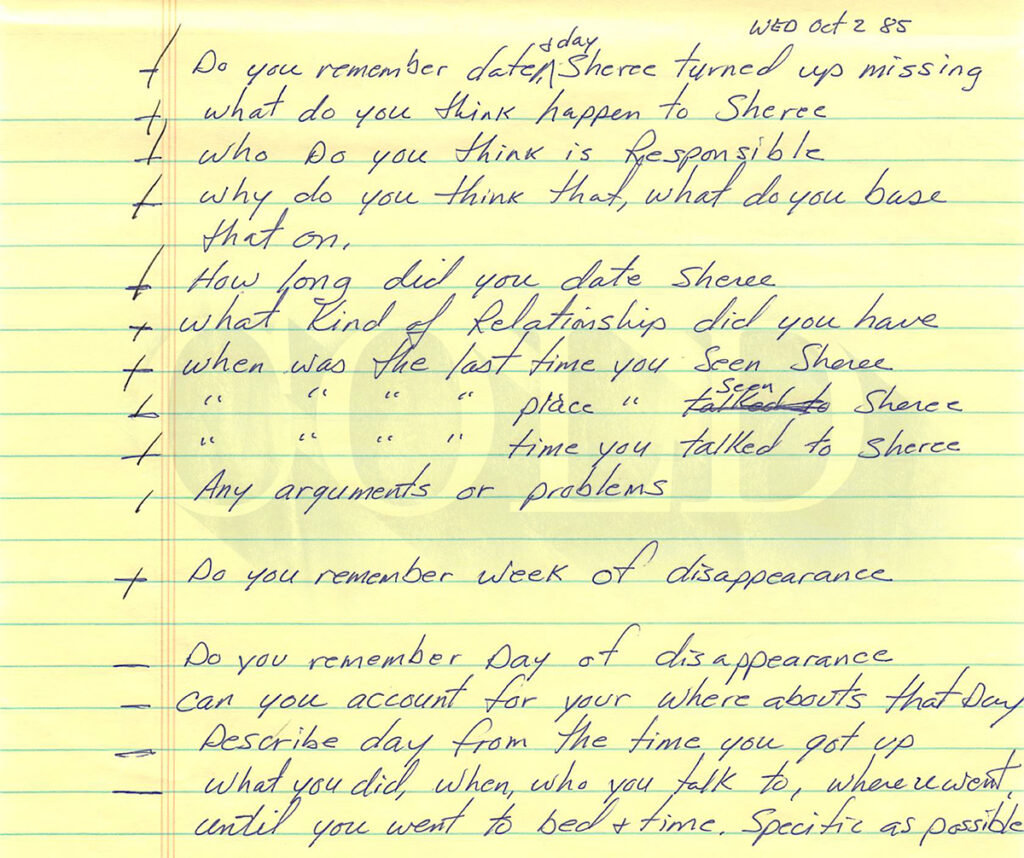

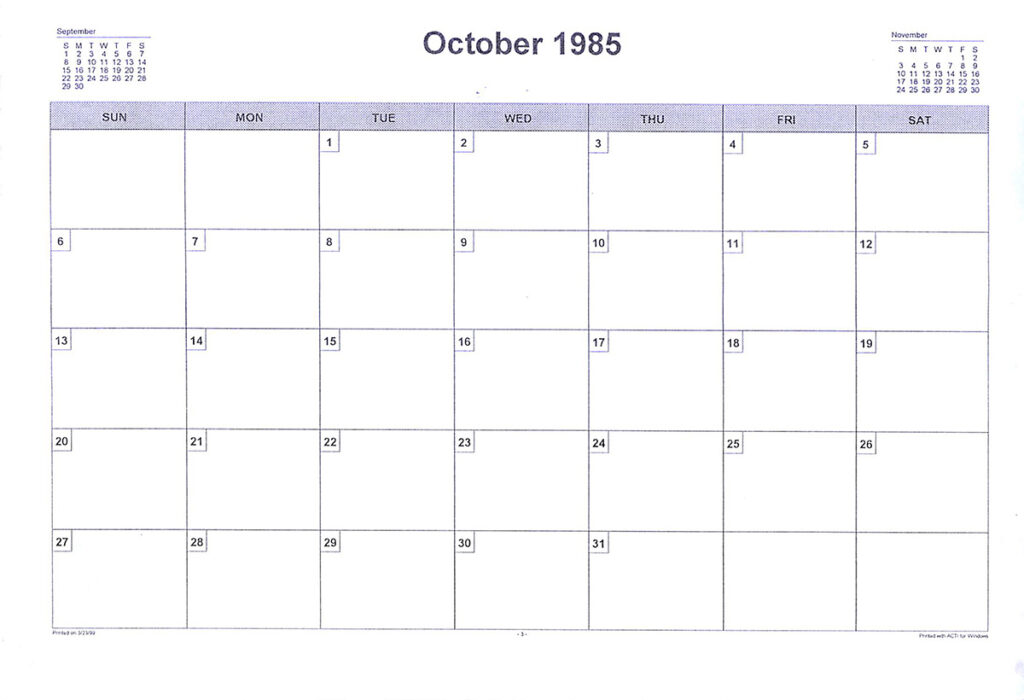

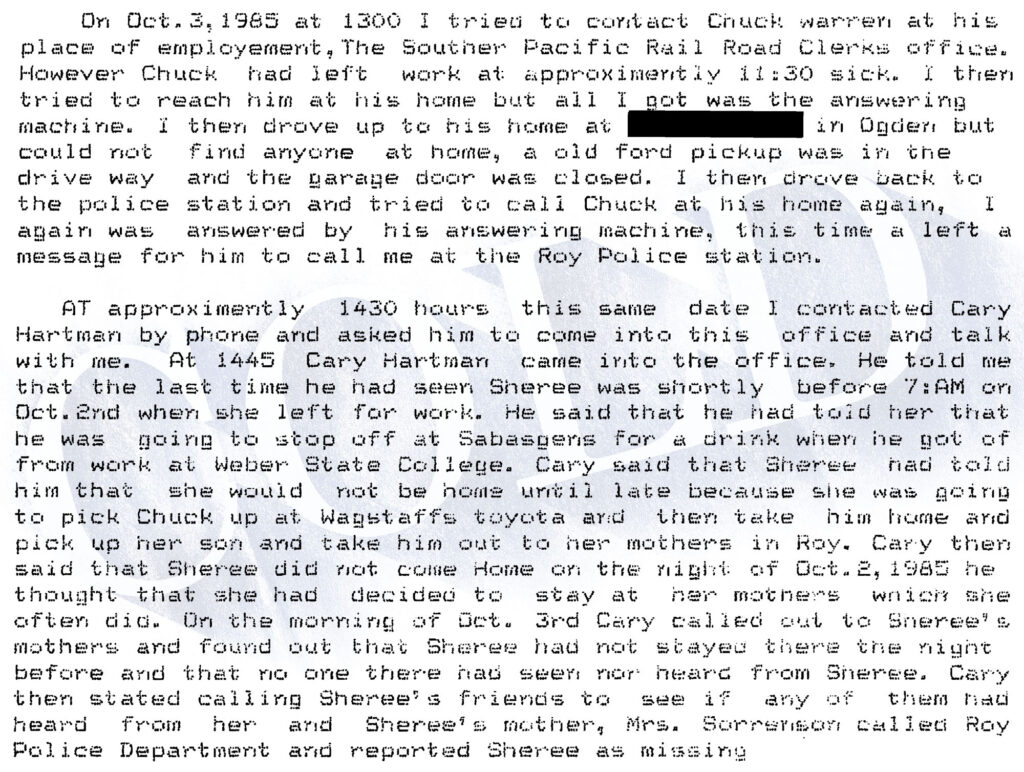

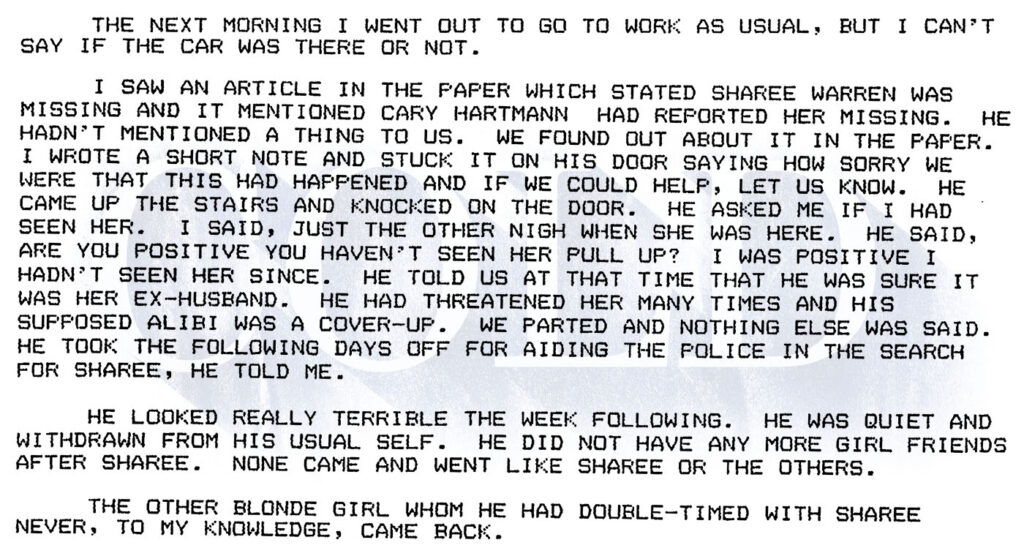

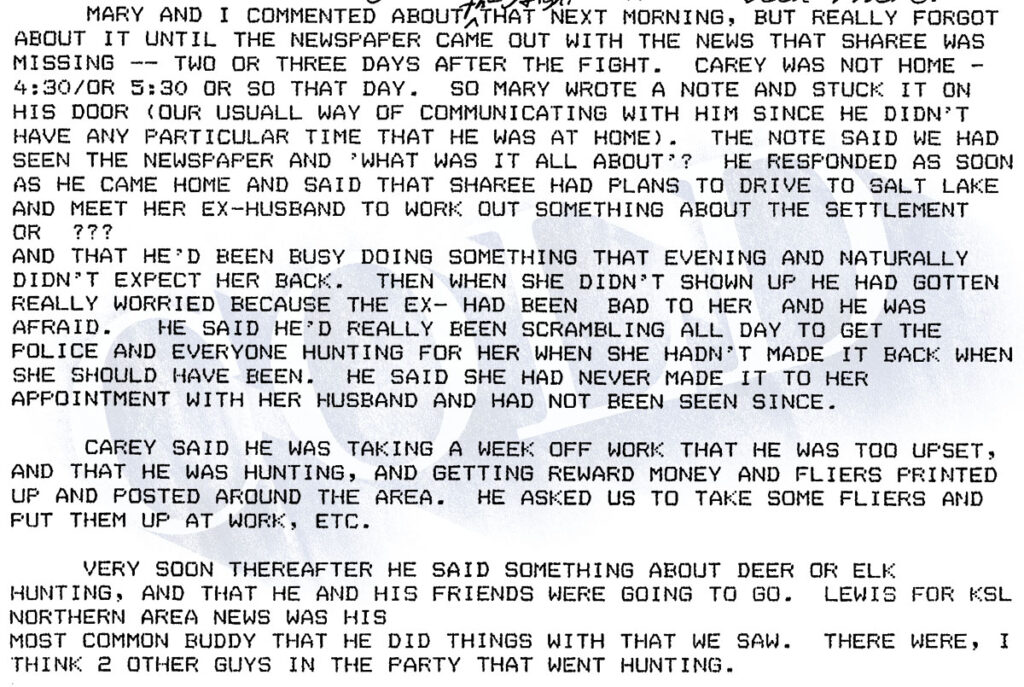

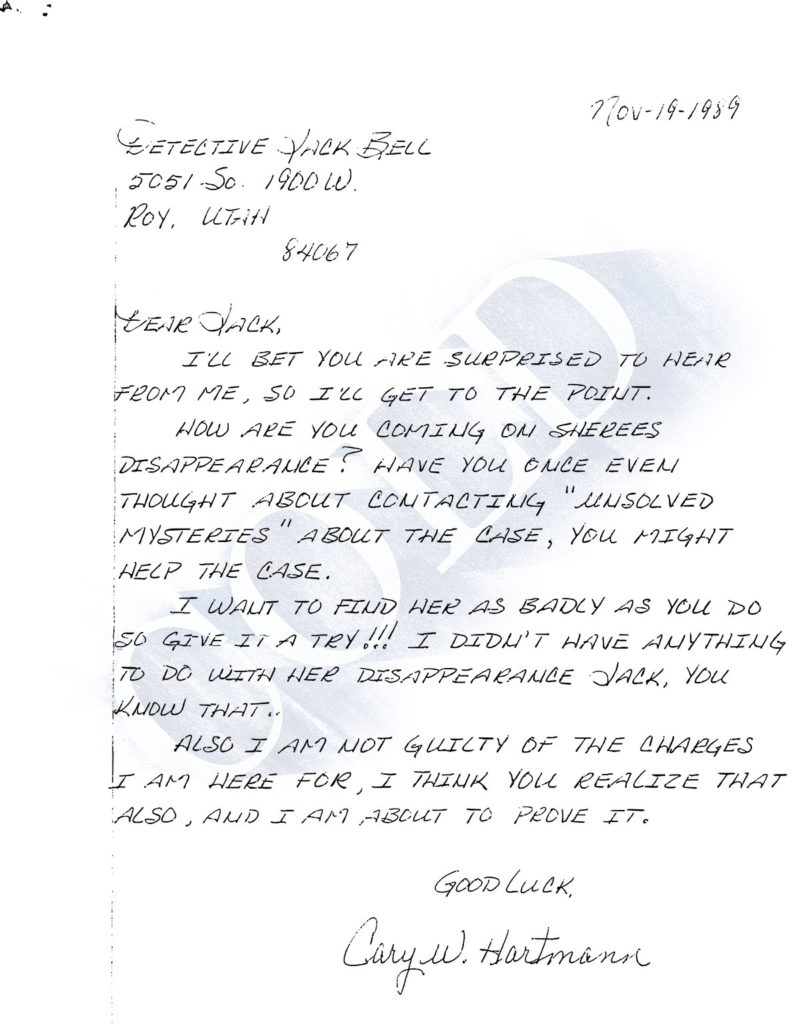

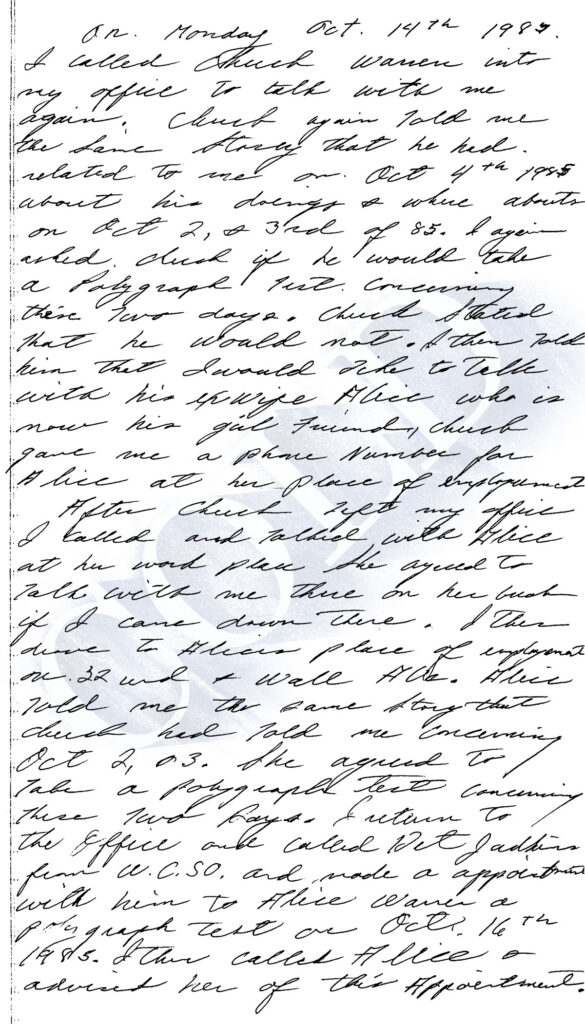

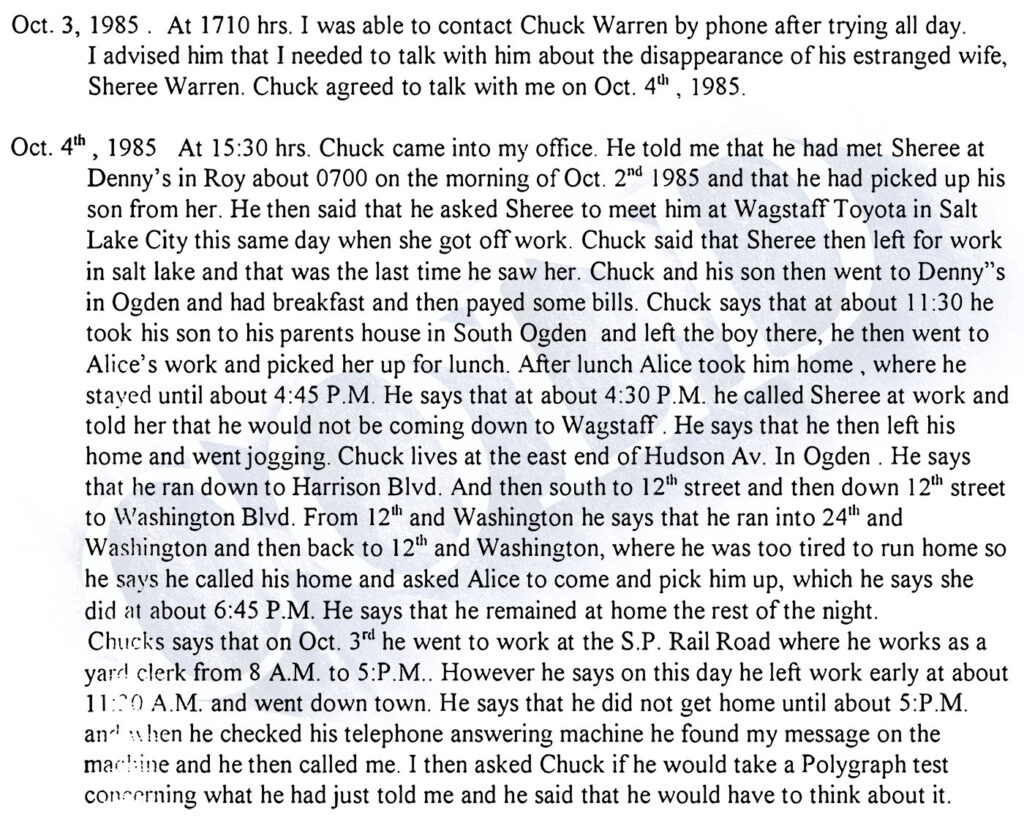

The initial investigation of Sheree’s disappearance on Oct. 2, 1985 had fallen on the shoulders of a detective named Jack Bell. By 2015, Bell was on the road to retirement. But John Frawley studied Jack’s notes and reports. He learned Jack had initially suspected Sheree’s estranged husband, Charles “Chuck” Warren, might’ve killed her.

Jack Bell told COLD he’d interviewed Chuck Warren one time, but Chuck stopped cooperating once he was asked to submit to a polygraph examination.

John Frawley felt the time had come to try and interview Chuck Warren again. So, on June 23, 2015, John went to speak with Chuck at his home on the eastern end of Hudson Street in Ogden. He was met at the door by Chuck Warren’s wife, Willow Hendricks.

COLD obtained an audio recording of the interview John conducted. What follows is a transcript of the Charles Warren interview.

June 23, 2015 interview transcript

John Frawley: Hi, how are you?

Willow Hendricks: Good.

John Frawley: Good, can I come in?

Willow Hendricks: (Laughs)

John Frawley: (Laughs)

Willow Hendricks: I’m assuming you’re the detective?

John Frawley: Yeah, I am. My name’s John. John Frawley. Nice to meet you.

Willow Hendricks: Nice to meet you. He was just getting his shirt buttoned up.

John Frawley: Awesome.

Willow Hendricks: Come on in, Chuck. (Cat meows) What? No, you’re not going outside. (Cat meows) But, yeah? You’re not going outside. No. (Unintelligible)

(Willow in next room with Chuck, before Chuck enters)

John Frawley: Hello.

Charles Warren: Hey (unintelligible).

John Frawley: Doing well.

Charles Warren: (Unintelligible)

John Frawley: Oh, you’re fine, sir. My name’s John Frawley. I’m one of the detectives in Roy.

Charles Warren: Uh huh.

John Frawley: Appreciate your time, appreciate you letting me come over and talk to you. Uh, is, is there somewhere we could talk for a couple minutes?

Charles Warren: Sure.

John Frawley: It’s your house, I’ll follow you.

Charles Warren: Go where?

Willow Hendricks: I’d say go to the front room. (Laughs)

John Frawley: (Laughs)

Willow Hendricks: It’s the cleanest house, the cleanest room in the house.

Charles Warren: Ok. Come on and sit down.

John Frawley: Thanks.

Charles Warren: Oh.

John Frawley: Should I call you Charles or—

Charles Warren: Sure.

John Frawley: ‘Kay. I’ll just put my radio over there ‘cause, in case somebody calls me on it.

Charles Warren: Ok.

Charles Warren interview: Jack Bell’s notes

John Frawley: Umm, so uh, I’m here to talk to you. I’ve just, I was assigned a case a few months ago. Umm, Sheree Warren. Umm, what’d happened is, uh, some remains were found in Davis County. I don’t know if you saw that on the news or not.

Charles Warren: I didn’t.

John Frawley: Ok. It came down to, umm, a few different possibilities. Umm, and anytime something like that happens a lot of old cases are kind of re-opened and so the case was assigned to me. Umm, and I read through it and, uh, these, what they’d found turned out to be someone, y’know, obviously someone else but the case is reopened and, umm, I read through it and was wanting to know if I can just talk to you and help me answer some questions and clear some things up. I know that you’d talked to, (noise) umm, detective Bell, what, that was about 30, not quite 30 years ago but—

Charles Warren: Damn near.

John Frawley: (Laughs)

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: I—

John Frawley: And so, yeah. Go ahead Charles.

Charles Warren: I, (laughs), his notes would probably be the best source.

John Frawley: (Laughs)

Charles Warren: I, I uh [medical information redacted by Roy City Police Department].

John Frawley: Sorry to hear that.

Charles Warren: And uh, sometimes I can remember, uh, things of—

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: —but, what I said at that time, I, y’know, he’d have it all down, I would think—

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: —with how good he was at taking his notes—

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: —y’know.

Willow Hendricks: [Personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department]

Charles Warren: Well, that’s what I was telling—

John Frawley: Yeah, he was just telling me.

Willow Hendricks: Some of the things are kind of.

Charles Warren: Well, I have trouble remembering how to say different words.

John Frawley: Oh, ok.

Charles Warren: Y’know?

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: And sometimes I don’t. But it’s really funny how all this, like, I can’t remember, uh, stuff like that, y’know?

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: But, that far back, I, I, I was worried about my son because of the thing out in, in Roy, the shooting out there.

John Frawley: Oh, ok.

Willow Hendricks: The family dead.

Charles Warren: The family dead.

Willow Hendricks: The four dead.

Charles Warren: And it’s right close to where he lives, him and his grandfather.

John Frawley: Oh, really?

Charles Warren: And so I went out there yesterday—

John Frawley: Oh.

Charles Warren: The reason I drove out there is ‘cause I couldn’t remember their phone number. And I used to have a photographic memory where I could remember, I had a phone number—

John Frawley: Right.

Charles Warren: Y’know—

John Frawley: Right.

Charles Warren: I could remember it forever.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: Or even numbers off of cars.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: (Unintelligible) [Personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department]

John Frawley: Well I’m sorry, sorry to hear that. But I was wondering if, y’know actually reading through that, through that report I, I have, I, I, more questions, actually. I, and so that’s why I, y’know, it’s like “I’ll call Charles and—“

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: —“and maybe talk to him.”

Charles Warren: Well, ask me and I’ll see what—

John Frawley: Yeah. Well, I’d like to, if we could, maybe just go back to, umm, start from, start from the day that Sheree disappeared. Umm, October 2nd, 1985, I think that was a Wednesday. Umm, in the notes, umm, it says that, uh, you, you had, you had a child [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] at the time and that, uh, you guys did kind of a custodial exchange—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: —early, early that morning. Do you remember that, Charles?

Charles Warren interview: Sheree Warren’s last day

Charles Warren: Yeah. What I remember is we, every day, she went to work at, during the day and I, I went to work at night. And I, I would, uh, I would uh, (laughs), drop him, or, I’d go to, we’d go to Denny’s—

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: —is where we would go. She would drop him off at Denny’s. We’d have coffee together and she’d go to work.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: And then, the same in the afternoon. Uh, that was just the Monday through Friday of her—

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: —y’know.

John Frawley: Uh huh.

Charles Warren: Unless she had to work Saturday, too. But—

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: Y’know, I don’t remember whether she ever worked Saturday or, seems like she did but I don’t remember.

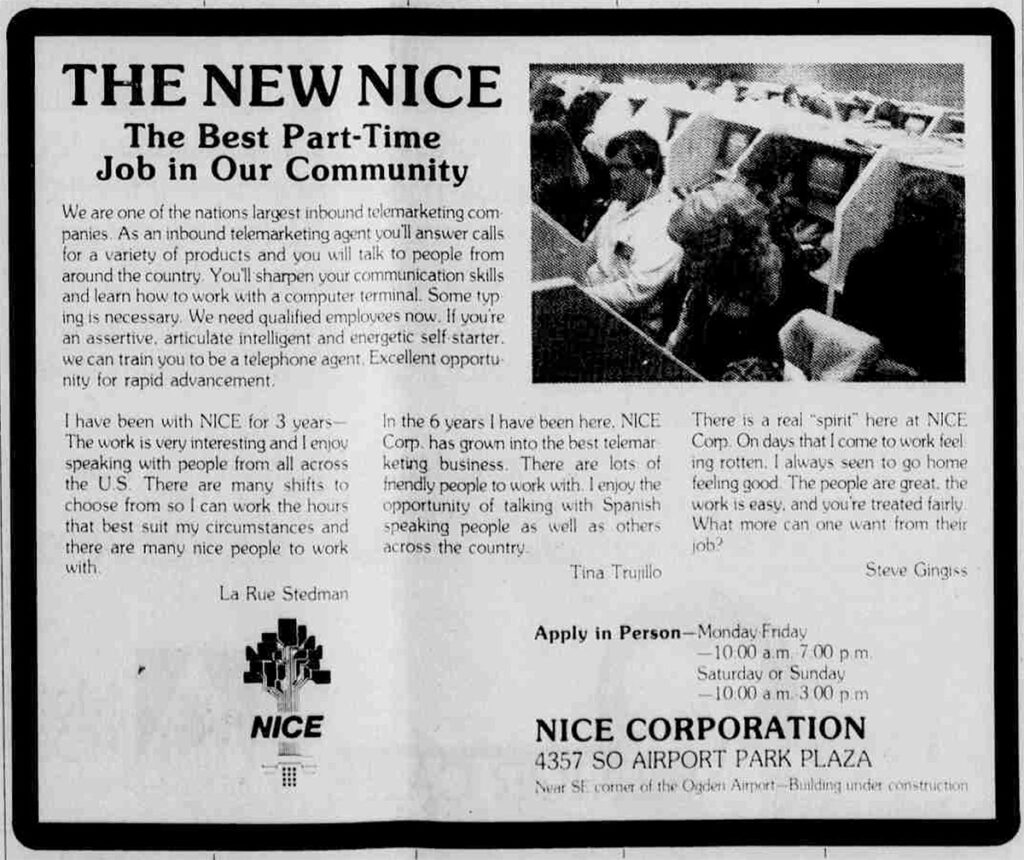

John Frawley: And so she was working down, she just got her new job down in Salt Lake?

Charles Warren: Yeah, she was becoming a manager, was gonna become a manager, something like that.

John Frawley: Yeah. To start training down there.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Umm, and then that, you had asked her to pick you up at Wagstaff Toyotas, or something like that?

Charles Warren: Yeah, yeah.

John Frawley: Ok. Can you tell me more about that?

Charles Warren: (Sighs) Well, I don’t, I never made it down there—

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: —and I called and told her—

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: —that uh, y’know, I wasn’t going to make it—

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: And uh, (pause), but I just never made it down there.

John Frawley: You never made it down there.

Charles Warren: Yeah. All I remember’s I, just never went down like I was supposed to but I did call her and uh, so I, y’know, I uh, I, I don’t know whether I talked to her or not. Seems like I did, but I can’t remember.

John Frawley: ‘Kay. You called down to the, you called I guess the bank?

Charles Warren: The bank, yeah.

John Frawley: But you’re not sure if maybe you talked to her or not or maybe?

Charles Warren: Uh, I, I think I did. It seems like I did, but—

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: —I’m not positive.

John Frawley: Ok. Umm—

Charles Warren: What, y’know, I probably told him what I did then, y’know?

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: He should, it should be in there.

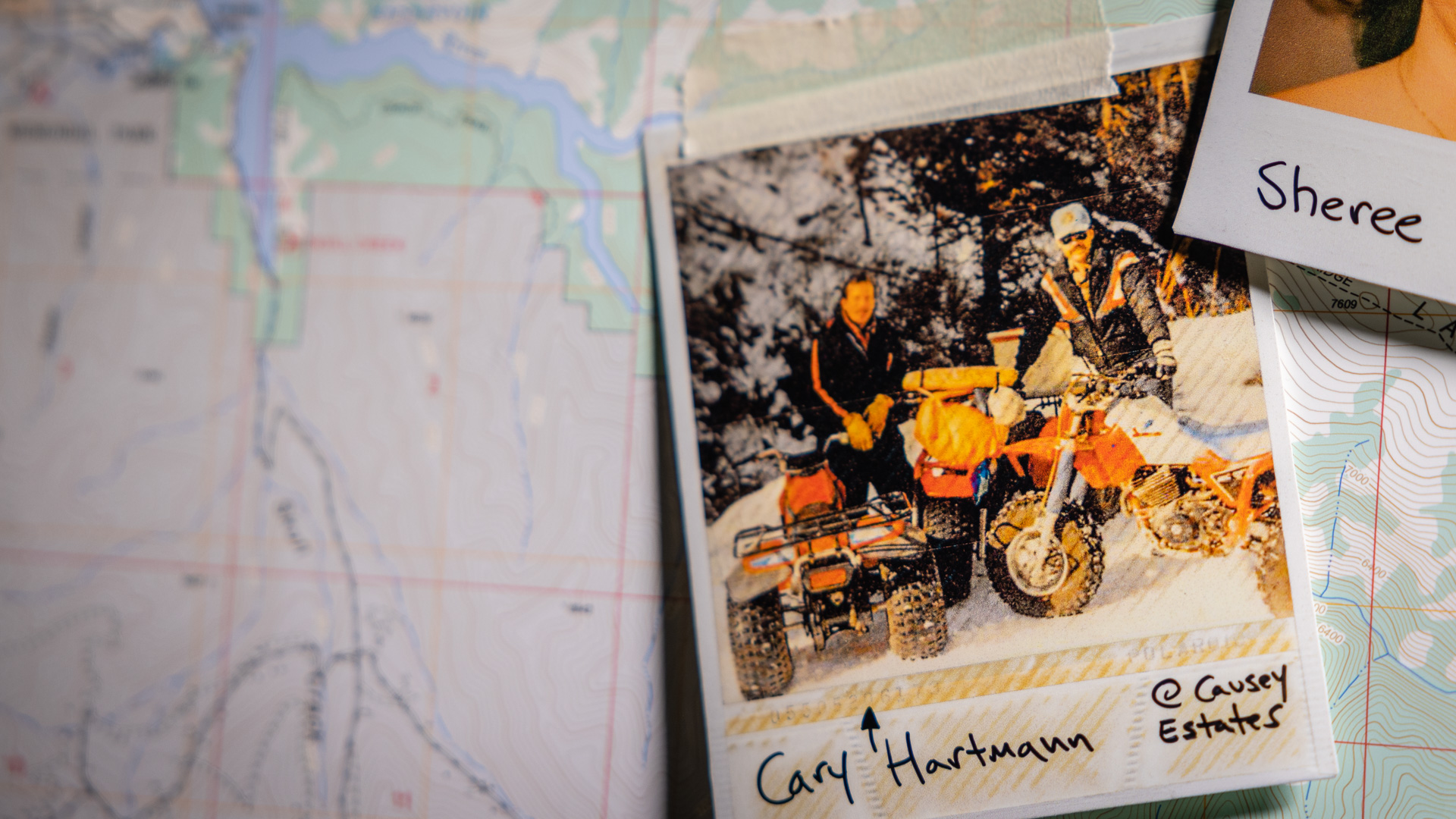

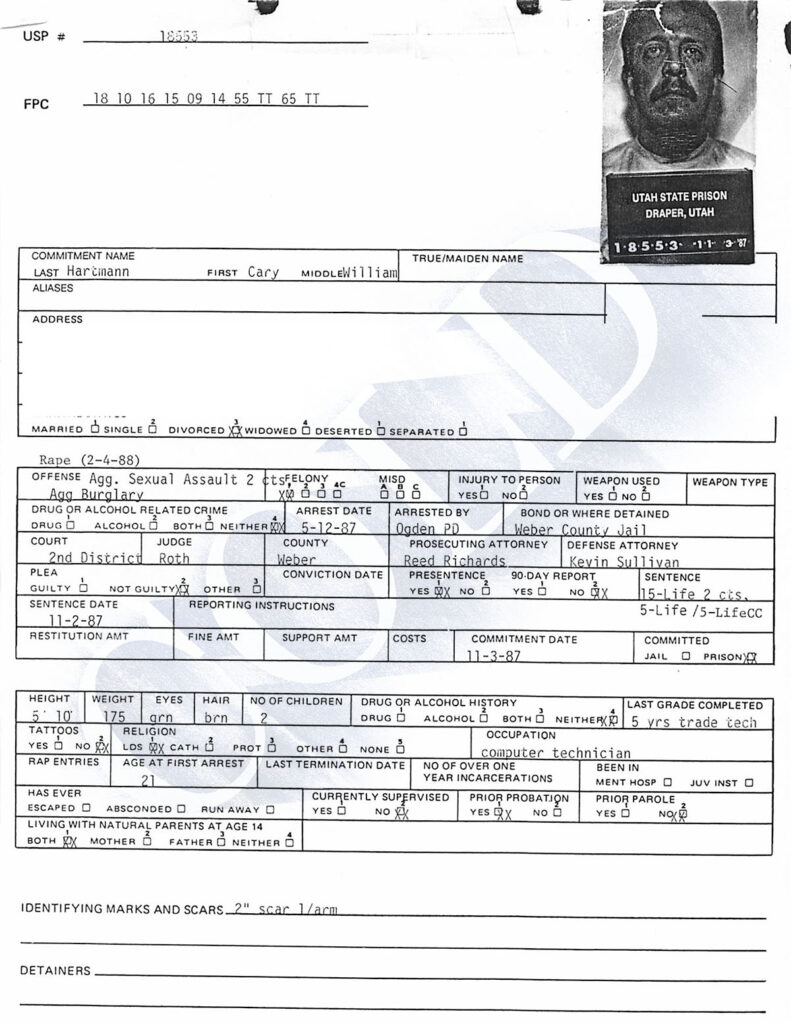

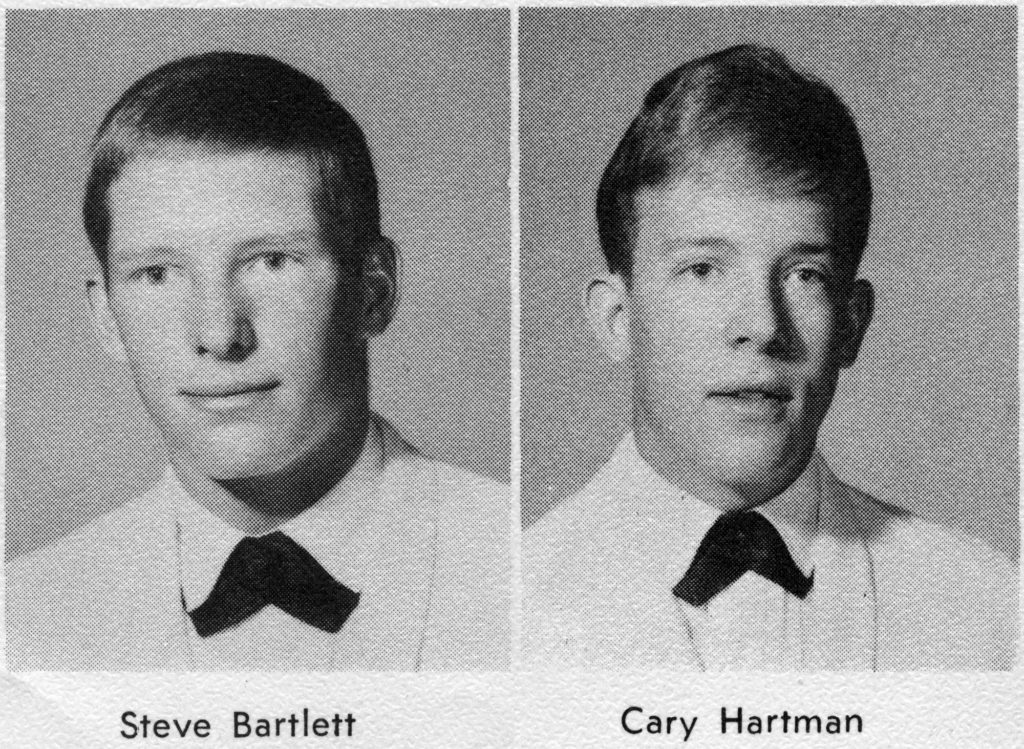

John Frawley: Ok. And so, and I understand at the time, umm, she was also dating, umm, a man named Cary Hartmann.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: How, how do you know Cary Hartmann?

Charles Warren: I don’t.

John Frawley: Oh, ok. (Laughs)

Charles Warren: I’ve never seen him before—

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: —I don’t, uh, I don’t know what even he looks like.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: So, where is he, by the way?

John Frawley: Cary Hartmann?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: I think he’s incarcerated right now, so—

Charles Warren: Still?

John Frawley: Yeah. Had uh, but had she ever, did you know about him at the time. I mean, did you know that she was dating him or?

Charles Warren: (Sighs) I can’t remember.

John Frawley: Can’t remember that?

Charles Warren: Uh, I, yeah, I just can’t remember if she—

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: —uh, when he got arrested it seemed like, and uh, then I heard something about that she’d been dating him.

John Frawley: That she’d been dating him, afterwards?

Charles Warren: And I think that’s how I found out, but I don’t know.

John Frawley: After—

Charles Warren: She’d never said anything to me about it.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: And I’d never asked—

John Frawley: Right.

Charles Warren: —so, y’know, ‘cause I was dating a lot of girls at the time.

John Frawley: Right. ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: So—

John Frawley: I’ve just got to make sure I can hear this radio. Umm, in the, do you, do you remember, in, in uh, detective Bell’s report he said that, umm, Alice [personal information removed by COLD] had picked you up, somewhere. Do you remember that at all?

Charles Warren interview: Out for a jog

Charles Warren: Uh, yeah. Yeah, I was out jogging. That’s what I was doing, I was out jogging.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: I, I went too far—

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: —and, uh, she picked me up at Denny’s—

John Frawley: Oh, ok.

Charles Warren: —on 12th.

John Frawley: 12th and?

Charles Warren: Washington.

John Frawley: Oh, ok.

Charles Warren: 12th Street and Washington. I was in there—

John Frawley: So you were in the Denny’s. Did you call her from the Denny’s to come get you?

Charles Warren: Yeah. Or, yeah I think I did. I must have. (Laughs)

John Frawley: ‘Kay. It’s a long, I’m brining you back pretty far here, Charles.

Charles Warren: Yeah, I must have—

John Frawley: (Laughs)

Charles Warren: I can’t remember whether I had a cell phone or not then. I know I was, don’t think, I don’t know. I don’t think I did—

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: —but maybe I did, I don’t know.

Willow Hendricks: Oh, you had a lot of the first ones that came out so you might’ve but—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

Willow Hendricks: —I don’t know.

John Frawley: What, so you did have a cell phone a long time ago?

Charles Warren: I, I did a long time ago but I don’t know whether I had it that time. That was, uh, ’85?

John Frawley: Yeah, ’85.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Did you have a cell phone in ’85?

Charles Warren: I don’t know for sure.

John Frawley: Possibly?

Charles Warren: Seems like, I don’t know. I can’t remember what year I actually got it.

John Frawley: Would’ve been one of the first ones coming out, and—

Charles Warren: Yeah, yeah.

John Frawley: —I mean, I remember those big ones.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: (Unintelligible)

Charles Warren: Well, see and, that’s when they were out and I didn’t get one until they come out with the StarTac.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: So—

Willow Hendricks: (Unintelligible)

Charles Warren: —that was the first one I had.

John Frawley: StarTac?

Charles Warren: Yeah, it was a Motorola—

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: —think it was StarTac. Or star, wasn’t Star Trek but it was StarTac. They were playing off it, and — I think, I don’t know. But it was, it was still about that big—

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: —and uh, but it was round and about that long.

John Frawley: Uh.

Charles Warren: And I don’t know what year I had it.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: If I, and it had to’ve been later. I know I had it in ’88.

Willow Hendricks: Is it the one I still have down the hall?

Charles Warren: Might be, yeah. Might be.

John Frawley: It’s your very first one and you still have it?

Willow Hendricks: (Laughs)

Charles Warren: Yeah.

Willow Hendricks: He, he keeps everything.

Charles Warren: I saved all of ‘em except the ones that got stolen.

Charles Warren interview: A change of plans

John Frawley: Can you, can you tell me, Charles, how, what changed, what changed your plans. Why didn’t you go to Wagstaff? Do you remember that?

Charles Warren: Uh, I was looking at cars, I think and uh, I uh, or something was wrong with my car. I can’t remember. And, umm, I don’t know. Shit. I don’t know.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: I remember calling her, I think I was calling her to tell her I wasn’t coming. Yeah, seemed like it was right around 4 o’clock or something that I called. I’m not sure.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: Somewhere in there.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: And he should have a record of that.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: Uh, ‘cause I’m sure he checked phone numbers, phone calls.

John Frawley: ‘Kay. Umm, so you [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] then, right?

Charles Warren: Uh, no. Her parents [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department].

John Frawley: I thought you guys exchanged early in the morning.

Charles Warren: We, we usually did but I was busy doing something else.

John Frawley: Oh, ok.

Charles Warren: Oh wait a minute, I [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department]. Yep. That’s sure. Yeah.

John Frawley: Did you find it strange that she didn’t come and pick [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] that night?

Charles Warren: Well, that’s when I called her parents about 9 or 10 o’clock at night. Somewhere in there.

John Frawley: Is that when she was supposed to pick him up?

Charles Warren: No, no. She was supposed to come pick him up, uh, when she got off work.

John Frawley: So that’s—

Charles Warren: So—

John Frawley: —that’s odd, then, right? I mean, that would’ve been strange.

Charles Warren: Yeah. Well, yeah but, y’know, uh, you had no other way of getting ahold of her, so—

John Frawley: She didn’t have a—

Charles Warren: —y’know, you have to wait ‘till she comes. I don’t think so.

John Frawley: She didn’t have a StarTac. (Radio noise) 10-4, thanks.

Charles Warren: Yeah, I didn’t [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department]. I remember that.

Willow Hendricks: Was Alice helping you out—

Charles Warren: Alice was here, too.

Willow Hendricks: —helping you with the boys at that time?

John Frawley: So did Alice also watch, watch the boys?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Ok. But, but the plan was that Sheree would [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] —

Charles Warren: Right.

John Frawley: —and bring him back to Roy, right?

Charles Warren: Yeah, ‘cause that’s where she, she was living with her, or she had an apartment, didn’t she?

John Frawley: She was living with Ed and—

Willow Hendricks: Mary.

John Frawley: —Mary.

Charles Warren: Mary.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: I remember her having an apartment, though. Somewhere.

Willow Hendricks: But was that at that time?

John Frawley: I think, I think—

Charles Warren: I don’t, I don’t know.

John Frawley: —I think for a short time, she did but at that time she was living with Ed and Mary.

Charles Warren: Ok.

John Frawley: Umm.

Charles Warren: Must’ve been, ‘cause that’s why I called them.

Charles Warren interview: Putting pieces together

John Frawley: ‘Kay. Alright, so this, this helps quite a bit, Charles, actually put these pieces together because, umm, y’know, I’m working off of a report from a long time ago—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: —y’know, you, you say you can’t remember too much but, y’know, you’re doing pretty good. You—

Charles Warren: Well as you’re bringing it up, I can remember a few things.

John Frawley: Awesome.

Charles Warren: Umm, but I’m not positive about, y’know.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Willow Hendricks: He’s been a pretty easy-going guy, too. So when she didn’t actually come pick him up at that time he probably wasn’t too worried about it. She’d be there eventually.

John Frawley: She, if she didn’t come right after work she would probably come—

Willow Hendricks: Just because he’s, y’know, because so easy-going, if you go do something it’s ok, just, but that’s, that’s probably why he didn’t worry at that time. Because he’s that kind of a person.

Charles Warren: Well, I (unintelligible) worrying about it one way or the other. But uh—

Willow Hendricks: Because that’s how you are.

Charles Warren: Yeah, until it got around 9, 10 o’clock.

Willow Hendricks: Yeah.

Charles Warren: So.

John Frawley: So what did you do when you started worrying about it, Charles?

Charles Warren: Well, I got on the phone and called her mom.

John Frawley: Oh, you did. ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: And umm, talked to her and she didn’t know anything or, so.

John Frawley: Did she become concerned?

Charles Warren: Uh, yeah, yeah. She was. She was, I believe, yeah. I don’t remember what I said to her, but, umm, I just don’t know. Umm, it was like, uh, I don’t know. I don’t remember—

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: —what I said to her.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: I remember calling her to find out where she was at—

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: —that’s what I was interested in.

John Frawley: Because generally, [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department], stay the night with, with them? Correct?

Charles Warren: Yeah, yeah.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: Because I’d be going to, normally I’d be going to work at uh, what time did I go to work? Midnight.

John Frawley: Oh, ok.

Charles Warren: Midnight to 8.

John Frawley: You worked 12 to 8, midnight to 8?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Oh, ok.

Charles Warren: Yep, and then uh—

John Frawley: So there’s no way you would’ve—

Charles Warren: —it was just 8 straight hours. I’d be off at 8, just right at 8 and then I pick him up.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: She didn’t have to be to work until 9 or 10. I can’t remember which. 9 I think. And I think it was 9.

John Frawley: She had to be there at 9?

Charles Warren: I think so. I don’t know. Anyway, we had an hour to, ‘cause we usually sat in Denny’s and I had coffee there with her—

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: —y’know, so.

John Frawley: That makes more sense. ‘Cause if you met there, what time did you say you met there that morning? Would’ve been like—

Charles Warren: Well, it would’ve been right after 8 o’clock.

John Frawley: Oh, ok.

Charles Warren: A few minutes after 8, ‘cause I worked on 28th Street and I always got off right on time or a little early, y’know, and so I’d just go down to wherever we were gonna meet and, and then uh, just sit there and drink coffee.

John Frawley: Oh, ok. So, so when she doesn’t come up, what did, what did you end up [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] and Adam. What happened with him?

Charles Warren: Well, he stayed with me.

John Frawley: He did stay with you.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: I kept him until her parents, I can’t remember what the deal was. Umm, I just don’t remember.

Willow Hendricks: He had Alice here with [Charles and Alice’s son] George though—

Charles Warren: Yeah, and Alice was with George.

Willow Hendricks: —and he’d probably stay with Alice.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Because you had to work.

Charles Warren: Yeah, I worked at midnight, yeah.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: But I wouldn’t have him then, see. She’d, she’d have him.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: But after that, y’know, uh, Alice didn’t work ‘till 8 or 9. I can’t remember if she was even working at the time. I don’t remember—

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: —whether she was even working at the time.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: But uh, umm, anyway, uh, but, uh, (sighs) anyway, umm—

Charles Warren interview: Sheree’s car

John Frawley: So, so Charles, it sounds like, umm, she was driving that Corolla.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Umm, by the way, where’s that Corolla now, do you know?

Charles Warren: I don’t.

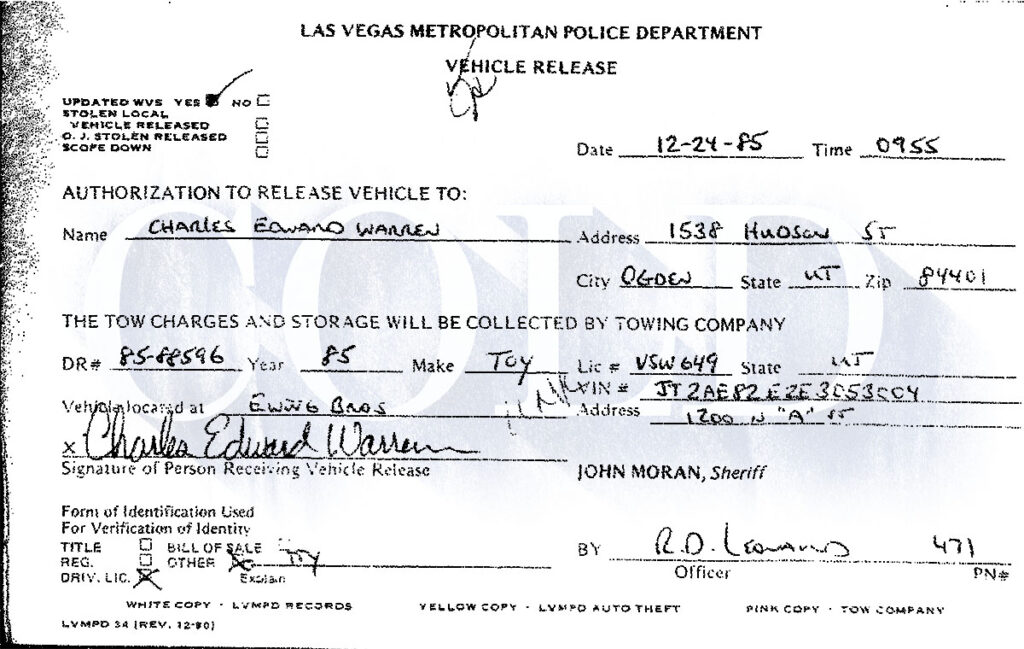

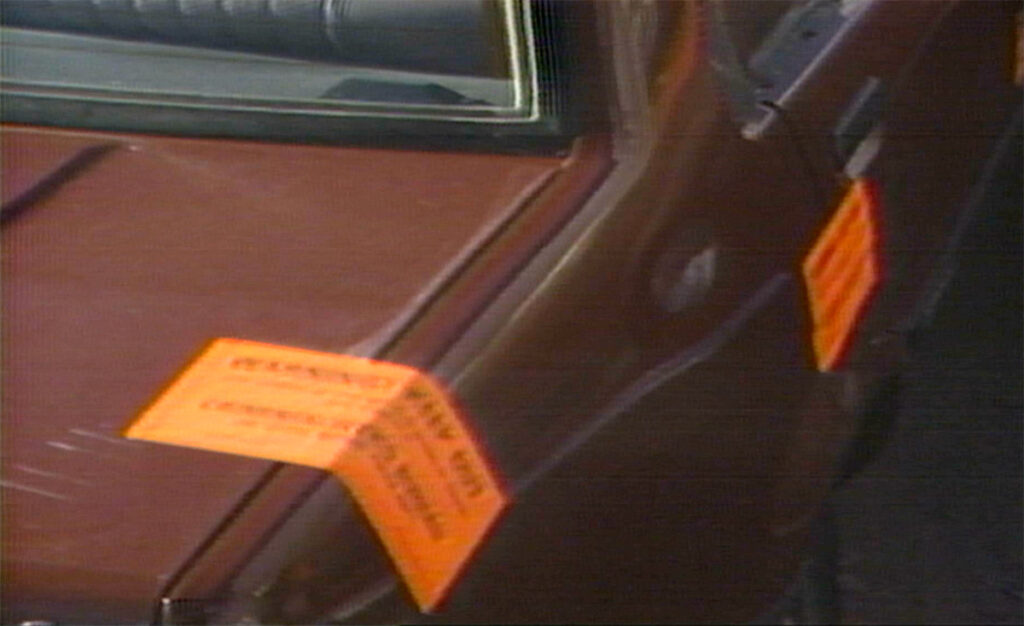

John Frawley: Ok. So she’s driving that Corolla and then the Corolla’s found, uh, November 11th in, at the Aladdin Hotel in Las Vegas. Umm, did you go down and pick that up ‘cause wasn’t it still registered to you?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: So you go down to pick it up. When did you go to pick that up?

Charles Warren: (Sighs) I don’t know. Can’t remember, uh, it was awhile, y’know? I had to, y’know, go down on my days off.

John Frawley: Oh, ok.

Charles Warren: And uh—

John Frawley: So it wasn’t right when they—

Charles Warren: No.

John Frawley: —told you it was there.

Charles Warren: No, no. Umm, but I wanted to get down there as soon as I can ‘cause they were charging storage and I can’t remember what it was.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: But it cost 300 or 400 dollars. Something like that, to get it out.

John Frawley: That was a lot of money right then.

Charles Warren: It was.

John Frawley: Umm, did you take any time off work after she’d been reported disappeared?

Charles Warren: No, I don’t remember doing that.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: I don’t remember doing that. But I, no I don’t think I did.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: The only time I took off work is, uh, is uh, when I was going partying. If I was sick, I went to work, y’know?

John Frawley: (Laughs) Yeah.

Charles Warren: So, I used my sick leave to go partying, not—

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: —y’know.

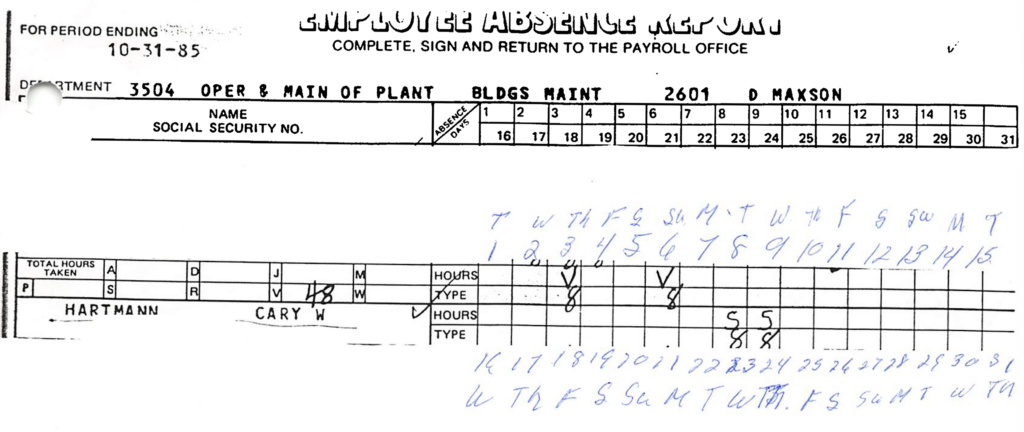

John Frawley: Umm, and you worked for the railroad. What did you do for the railroad?

Charles Warren: I was a clerk at that time.

John Frawley: Was that kind of in an office or was that traveling around?

Charles Warren: Uh, 28th Street yard office.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: Basically.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: I was the chief clerk there and, uh, on the afternoon shift for awhile and uh, for awhile on the midnight shift and, y’know, ‘till I got bumped and stuff like that. Umm, I think I only worked one day shift. But uh—

John Frawley: But this wasn’t like you getting on a train and traveling around—

Charles Warren: No, no.

John Frawley: —this was you working in an office.

Charles Warren: Just right there on 28th.

John Frawley: Ok, ok.

Charles Warren: So.

John Frawley: Ok. Umm, so you hadn’t heard about Cary Hartmann until actually after he is arrested.

Charles Warren: Right.

John Frawley: That, that Sheree had been dating him.

Charles Warren: It seems like somebody come up and asked me questions about him. Maybe it was [Jack] Bell.

John Frawley: Oh, ok.

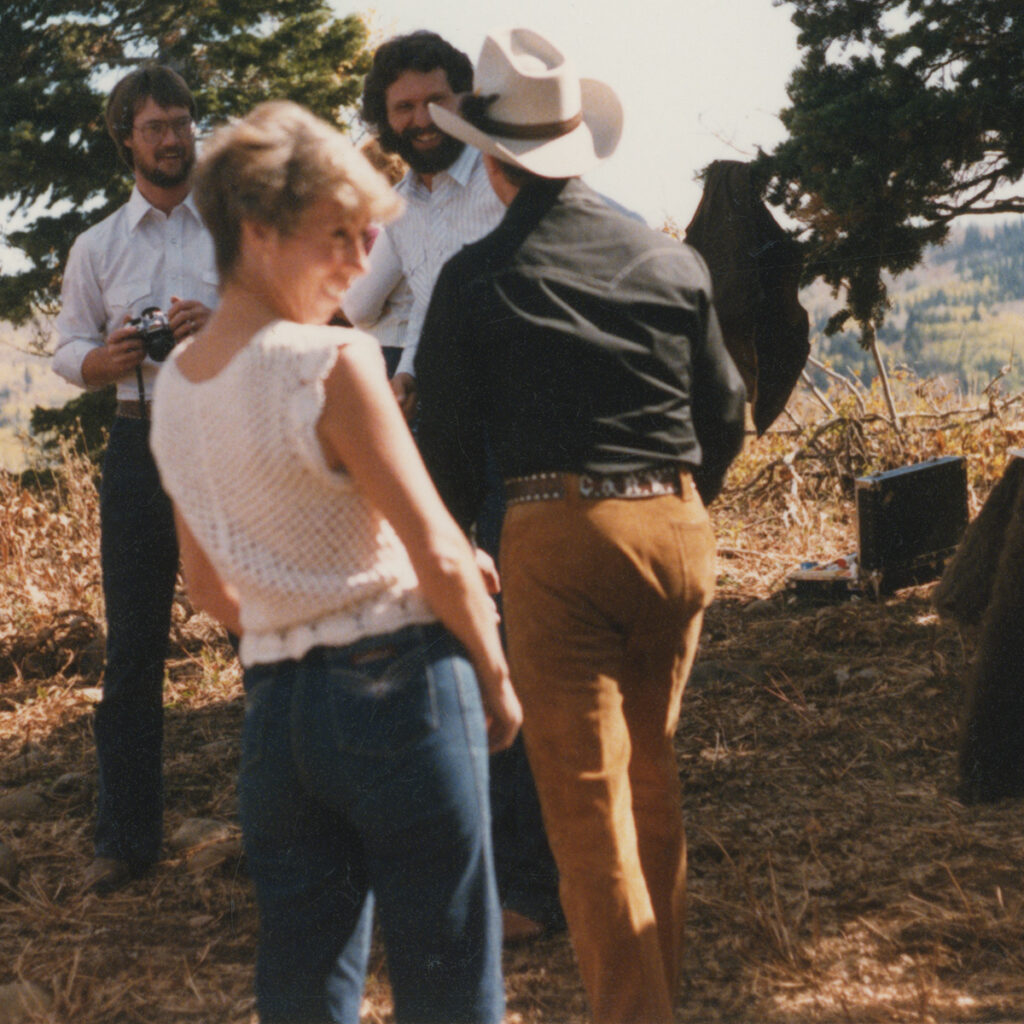

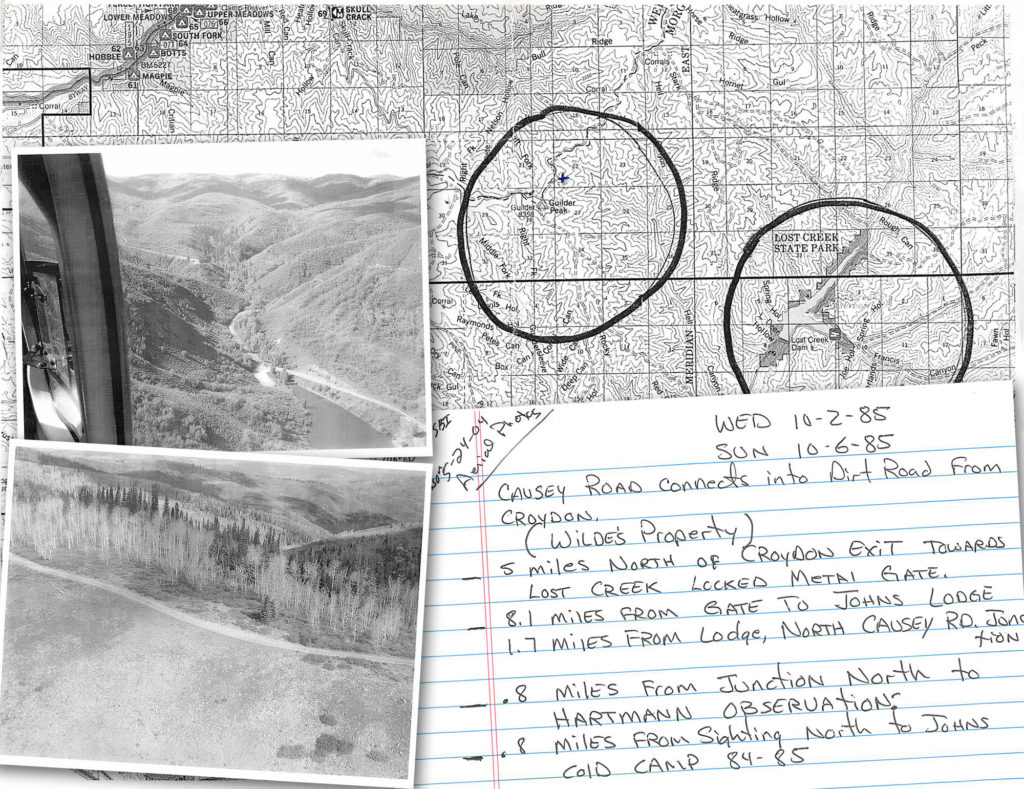

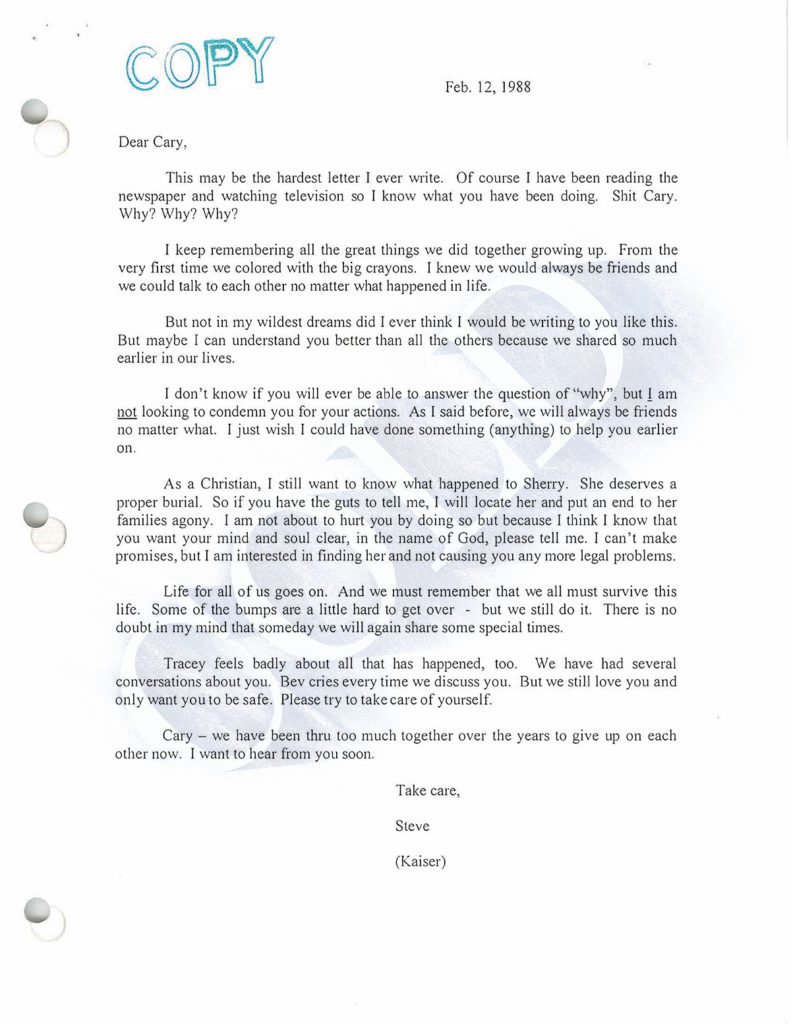

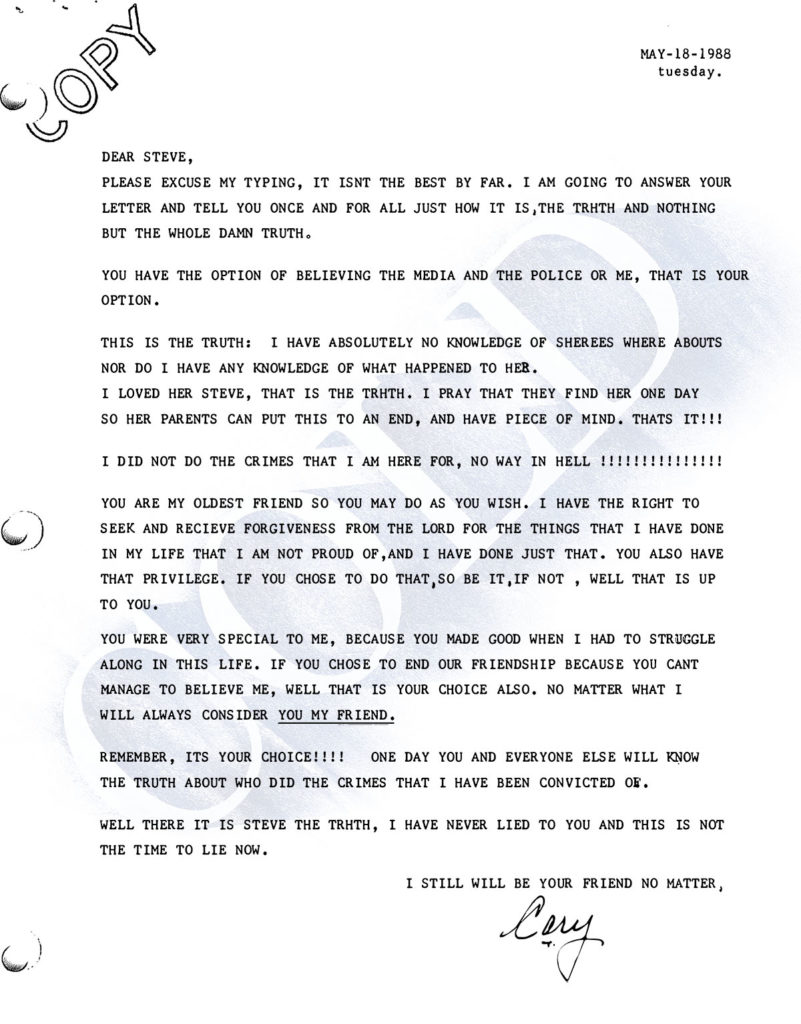

Charles Warren interview: Cary Hartmann’s psychic stories

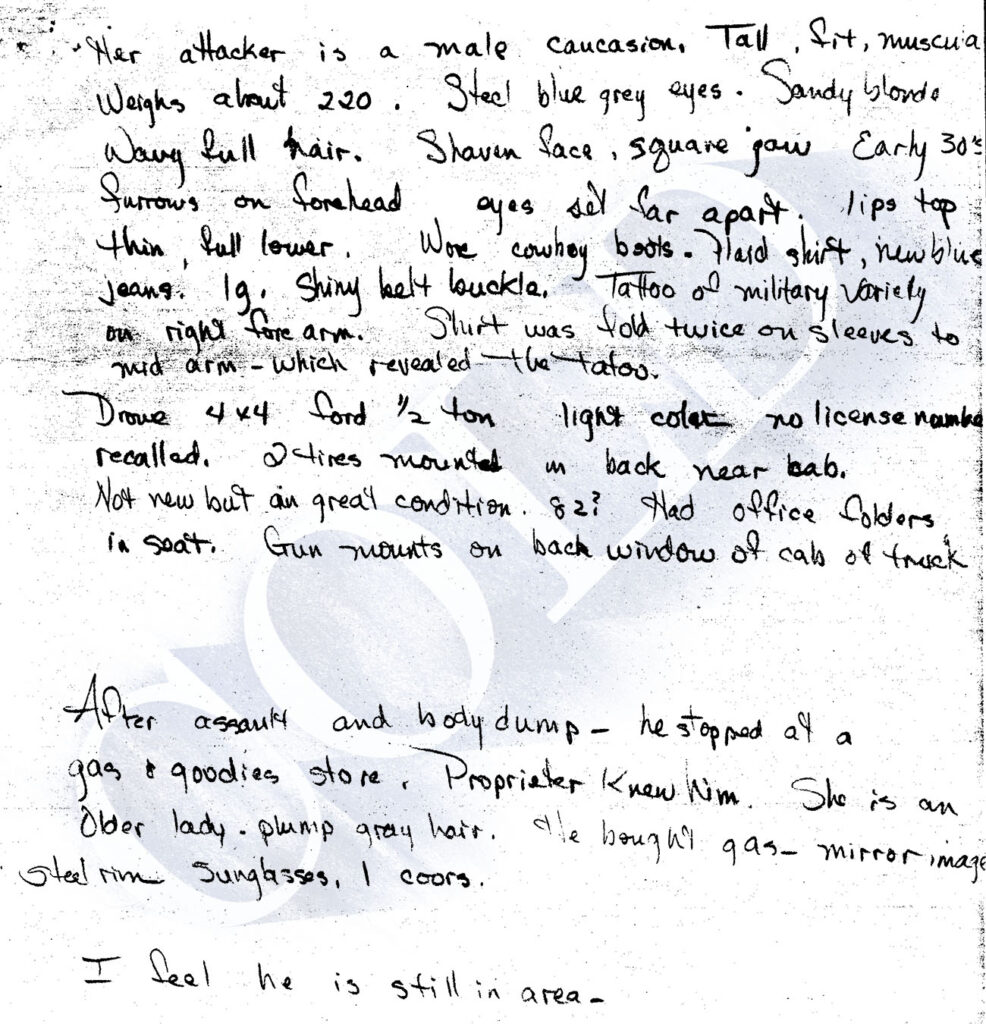

Charles Warren: I remember him telling me something about Hartmann had been telling him about, he had a dream, some sort of a dream about finding her up in Ogden Valley somewhere.

John Frawley: That he had a dream?

Charles Warren: He had a dream or one of his friends had a, he didn’t right that down, huh?

John Frawley: I’ll have to review that one. Umm, that she’s up in the mountain? He had a dream that she’s up in the mountain?

Charles Warren: That, yeah. Yeah. That they’d find her up there.

John Frawley: Hmm.

Charles Warren: And they was, I, I don’t know. You ought to, if he didn’t put it in there, then—

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: —I don’t think I dreamed that up.

John Frawley: (Laughs)

Charles Warren: I remember him telling me that, though, about some sort of a dream. Umm, something to do with a 4×4 pickup and uh, but I don’t know.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: I don’t, I can’t remember. That thought just jumped in there.

John Frawley: ‘Kay. Umm, he did, he did write that, I guess you went and talked to him on the 4th, would’ve been just a couple days after. He said that, in his report he said that, umm, so Sheree disappears on the 2nd. On the 3rd, you’d left work early ‘cause you weren’t feeling well or something like that. About 11:30 a.m., that you left work early and you, I guess he’d tried to call you. Did he, did he leave messages for you to call him?

Charles Warren: I wouldn’t have left work in the middle of the shift.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: Uh, not unless somebody called me and said they were in the hospital. And I don’t remember that. Umm, might’ve went to lunch. We had, supposedly a 20-minute lunch but sometimes I took an hour or so.

John Frawley: Take a little longer lunch.

Charles Warren: Yeah. Nobody, well everybody did. Everybody took an hour and a half. I tried, most the time I tried to stay under an hour.

John Frawley: Under an hour. ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: Uh—

John Frawley: So about 11:30’s probably the time you, is that, does that sound like the time—

Charles Warren: No—

John Frawley: —you took a lunch?

Willow Hendricks: He wouldn’t—

Charles Warren: —yeah, I could’ve, could’ve went to lunch at 11:30. But I don’t remember working days back then. And see—

Willow Hendricks: He wouldn’t have been at work at that time.

John Frawley: Do you keep any, uh, timecard records from that time? Do you have any records like that?

Charles Warren: No. (Laughs)

John Frawley: I know, she said you keep everything, so. (Laughs)

Charles Warren: No, no. Just phones.

Willow Hendricks: I have lots of checkbooks.

Charles Warren: (Laughs) Uh, let’s see here, uh, I can’t remember leaving work except (unintelligible) my dad once when he was in the hospital. I, oh, y’know Willow Hendricks:at I did one (sigh) ’88, ’89, ’89—

Willow Hendricks: So that wouldn’t have been—

Charles Warren: —no, it would’ve been ’90, ‘cause my mom died (unintelligible). My dad died in ’90 and I think the only time I ever left work, and I wasn’t working days then, but I was the agent.

Willow Hendricks: It wouldn’t have been the same time period, though.

Charles Warren: No, but that’s the only time I remember leaving—

John Frawley: So you weren’t—

Charles Warren: —go pick my dad up.

John Frawley: —you weren’t working 8-to-5’s in 1985? You weren’t working days?

Charles Warren: No, no. I don’t think so. I could’ve had one shift in there somewhere.

John Frawley: Oh, I see.

Charles Warren: I was, y’know, I worked, I bid jobs in but I couldn’t hold dayshift.

John Frawley: What were your days off?

Charles Warren: Uh, (laughs) depends on which jobs I was on.

John Frawley: Oh, I see.

Charles Warren: (Laughs) Most the days off I had was (unintelligible). Uh, shit.

Willow Hendricks: (Unintelligible)

Charles Warren: Monday and Tuesday or Tuesday and Wednesday. Stuff like that. I couldn’t hold weekends at all.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: Uh, and let’s see, I, uh, I, uh, like I said, I do remember leaving on a day shift one time to get my dad but back then, I wouldn’t have, I wouldn’t have left unless it was a total emergency.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: Uh, and if I was working a day shift at that time, it would’ve been extra, would’ve been overtime. I used to work, umm, I used to work 8, uh, how does it work? I worked, uh, 16 hours (unintelligible) I have 8 hours off. I’d go back to work again, I’d work another 16 and 8 off. Then I’d work 32, err, 24 straight and 8 off. And uh, uh, then I, uh, anyway, it amounted to I had, uh, a 32-and-a-half day half. In other words, I’d have, I got paid for equivalent of 32 shifts, uh, and, of overtime.

Willow Hendricks: Is that during the time (unintelligible).

Charles Warren: No that was, that was before she was gone.

John Frawley: But it seems like you remember—

Charles Warren: I remember certain things, yeah.

John Frawley: (Radio noise) 10-4, thanks. But it, but you’re, it sounds like you’re positive that you were working 12-to-8s, is that, is that what you’re saying? At that time?

Charles Warren: No, I’m not positive. What I remember—

John Frawley: Oh, ok. Ok.

Charles Warren: —no, I said if I, but I was, but y’know if I was working 24 hours, I worked days. That day, I’d be, uh, and I never, when I was working like that, I uh, never took off to lunch because I was really tired and the only way I could stay awake working that kind of hours is working on a computer, keeping my mind busy. And without doing that, that’s out right there. ‘Cause I can sleep just like this.

John Frawley: (Laughs)

Charles Warren: Y’know? But uh—

John Frawley: But, but you’re sure that she was, you’re sure that Sheree was supposed to come back and pick Adam [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department].

Charles Warren: Oh yeah.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: Yeah, there was no question about that. That’s why—

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: —I would’ve called.

John Frawley: And it was around, I’m sorry, forgive me, tell me again, 9 or 10 that you’re like “ok.”

Charles Warren: I know it was after, it was before 10 o’clock and after 9:30. That’s all I remember—

John Frawley: Ok, between 9:30 and 10 p.m. You’re—

Charles Warren: —somewhere in there.

John Frawley: —you call Mary and—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: —say “hey, where’s she at?”

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: And that’s, I don’t know what she did after that.

John Frawley: Mary?

Charles Warren: Yeah. If she got her kids out looking. (Laughs)

John Frawley: I, I think, y’know, I’ll have to review the case again, I think, y’know, I think she does call around, yeah, try to figure out where she’s at because I’ve talked to Ed. Ed said that she told them that morning “hey, don’t worry I’m not, I’ll be a little late, I’m supposed to meet Charles at Wagstaff Toyota”—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: —so she wanted to let ‘em know that she was going to be a little later getting over there.

Charles Warren: Mmhmm.

Charles Warren interview: Plan to meet at Wagstaff’s House of Toyota

John Frawley: Was that something you’d talked to her before that day?

Charles Warren: Oh yeah.

John Frawley: Ok. That was planned the whole—

Charles Warren: Set up.

John Frawley: —set up?

Charles Warren: Yeah, before. And uh, and uh, then it didn’t happen, so—

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: —I called and told her I wasn’t gonna make it. So.

John Frawley: Ok. You don’t remember why you didn’t go down though, right?

Charles Warren: I don’t.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: Nope—

John Frawley: Was it—

Charles Warren: —it might’ve been a shift that came up or, no, it couldn’t have been a shift. Nope. I don’t remember.

John Frawley: Is this the Supra right out here on your driveway? Is that the one you were gonna go bring down to get fixed, that’s Toyota’s—

Charles Warren: No.

John Frawley: —oh, ok.

Charles Warren: No, it was a black, uh, ’85.

John Frawley: Oh, ‘kay.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

Willow Hendricks: (Unintelligible)

Charles Warren: That’s the one I should’ve kept.

John Frawley: Is that a Supra, too?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: And then the other one I should’ve kept was an ’88 turbo I had—

John Frawley: Oh wow.

Charles Warren: —I really should’ve kept. It was leased—

John Frawley: Oh.

Charles Warren: —I couldn’t afford to pay double for it.

John Frawley: Right. They kind of get you on that—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: —the whole lease program.

Charles Warren: And then after that, Supras got too expensive and I couldn’t afford. (Laughs)

John Frawley: (Laughs) Well, you’ve got this one out here still.

Charles Warren: Well, I was only paying 8 and $10,000 for it—

John Frawley: Ah.

Charles Warren: —or no, I was paying 12 to $14,000 for it. For maybe ’83 to ’85 and then after that the price went way up—

John Frawley: Oh did it?

Charles Warren: —after the—

John Frawley: For like what?

Charles Warren: —yeah, I paid $25,000 for my, my uh, turbo, ’88 turbo.

John Frawley: Oh.

Charles Warren: And that was a lease, y’know. So, y’know they went up above $30,000 to buy. (Laughs)

John Frawley: Yeah, yeah.

Charles Warren: By ’88, so, that’s the reason I leased it.

John Frawley: Well I appreciate you talking with me. Like I said, this case, y’know, it’s open. It’s an open case but I, questions come up, y’know and—

Charles Warren: I can’t help you with ‘em.

John Frawley: Oh you did, actually. You helped me quite a bit. Umm—

Charles Warren: Like I say, there are bits and pieces but, of everything.

Willow Hendricks: Alice might be able to fill some in, too. ‘Cause she was around helping [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] too. Especially after she went missing.

Charles Warren: Yeah, and that was after.

Willow Hendricks: Yeah, but she was still [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department]. You told me that.

Charles Warren: Well, she was actually living down the street at that time.

John Frawley: At that time, Alice was just down the street?

Charles Warren: Yeah, (unintelligible) house. Then she come up after that. And uh, stayed here. Or, I think that’s how it went. Can’t remember whether she came up here first or went down there first. I can’t remember. But anyway, she was here, uh, watching uh [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] that night for sure. Y’know. Uh, because she came and picked me up—

John Frawley: After your—

Charles Warren: —at Denny’s.

John Frawley: —after your jog.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: She picked you up at the Denny’s.

Charles Warren: Yeah. And then, uh, let’s see, what’d I do? I don’t remember doing anything that night after that. Went to bed early. I don’t remember when I went to work the next day or if I did. I don’t know. (Laughs) That I can’t tell you.

John Frawley: It’s a long time ago.

Charles Warren: Yeah, but uh, (sighs) I remember when I start talking to [Jack] Bell, whether it was a week after or, and uh (noise) can’t remember. What day did, did it show he interviewed me the first time.

John Frawley: October 4th.

Charles Warren: So—

Willow Hendricks: Two days after.

Charles Warren: —two days after, then.

Charles Warren interview: Chuck’s whereabouts

John Frawley: Yeah, so this is his, in his report he said that, umm, uh, he, he’d been, uh, calling, leaving messages on your phone. He actually even stopped by, you lived here, right? You were here—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: —so he stopped by here, couldn’t get you at the door. Uh, that was on the 3rd, October 3rd. Umm, he, he, he’d, he was under the impression you left work early and then, you went to the police department on the 4th and talked to him.

Charles Warren: I see.

John Frawley: And uh, in his report, he says that, umm, you, you and Sheree met at the Denny’s at 7 a.m., around 7 a.m.

Charles Warren: Couldn’t have been 7.

John Frawley: Couldn’t have been 7?

Charles Warren: No, I’d be, I worked ‘till 8.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: I wouldn’t have left an hour early. (Laughs)

John Frawley: So, so he’s saying it’s around—

Charles Warren: So he’s off there if it’s what he wrote down.

John Frawley: —it’s around 7 a.m., umm, you guys do a custodial exchange, you talk to Sheree about Wagstaff, picking, picking you up at Wagstaff Toyota down in Salt Lake, giving you a ride, she agrees to that. She drives to Salt Lake, you bring, umm, [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] to the Denny’s in Ogden, I guess, and have breakfast at the Denny’s in Ogden.

Charles Warren: Uh, no she brought [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] to Denny’s and I picked him up there.

John Frawley: No, in Roy.

Willow Hendricks: In Roy.

Charles Warren: Oh, in Roy. Yeah. Yeah and that’s—

John Frawley: —I’m just—

Charles Warren: —that’s the way we’d go—

John Frawley: —I’m just telling you what—

Charles Warren: —I didn’t remember Roy but I think that’s right.

Willow Hendricks: I remember you telling me Roy.

Charles Warren: Ok. I must’ve, I must’ve used to drive out to Roy and, and drop him off there, exchange him back.

Willow Hendricks: Because it’s close to her house.

John Frawley: Umm, so I’m just telling you what’s in the report.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: And so, and then—

Charles Warren: Well, I must’ve, because I, I don’t remember it but I do, it must’ve been—

John Frawley: The report—

Charles Warren: —that way.

John Frawley: —the report says you actually drop [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] house.

Charles Warren: No, no. Uh, once in awhile I would but—

John Frawley: But actually, Alice said she had [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] so does that—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: —does sound more correct to you?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Ok. Uh, then it, it actually says that you and Alice go to lunch.

Charles Warren: Uh, that day?

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: I don’t remember that, but—

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: —but we could’ve, I don’t know.

John Frawley: Then, you called the bank at around 4:30.

Charles Warren: Somewhere in there.

John Frawley: Yeah, 4:30. And uh, after that you go for a jog and you actually give your whole jogging route to him.

Charles Warren: Mmhmm.

John Frawley: Told him where you jog and how you ended up down on 12th and Washington. I didn’t know it was a Denny’s but—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: —that probably, that sounds about right.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: That you’re saying the same thing. Umm, so, and then Alice picks you up at 12th and Washington and brings you here.

Charles Warren: Mmhmm. Yeah. And I can’t even remember what time that was, though. It was probably around 6? I don’t know. I don’t know. 7 or, 7 or 8. Somewhere in there.

John Frawley: That she picked you up at 12th and Wash?

Charles Warren: Yeah. Might’ve been before that. Seemed like it was dark, though.

John Frawley: It was dark when she picked you up?

Willow Hendricks: Well, it would’ve been getting dark about 6 or so then.

Charles Warren: Yeah, it was dark or something but, I umm, yeah. That’s why I decided I didn’t want to walk home.

John Frawley: Yeah, yeah. I was just going to say, do you always run in the dark? (Laughs)

Charles Warren: No, no. No, it seemed like it got dark and that’s why I went to Denny’s and had coffee and then I called her and had her come pick me up.

John Frawley: Oh ok, that makes, that makes, so you go, you go for a jog and then you’re there at the Denny’s having some coffee and she picks you up.

Charles Warren: Yeah, I drank a lot of Denny’s coffee.

John Frawley: (Laughs) Do you still drink it?

Willow Hendricks: He does. Yes, he does.

Charles Warren: Yeah. That’s where I’m going.

John Frawley: For lunch?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

Willow Hendricks: You’re going to meet a friend.

Charles Warren: Yeah, Joe.

John Frawley: Ok, well I don’t want to, I don’t want to hold you up. I—

Charles Warren: What time is it? Uh, oh it’s (unintelligible) time.

John Frawley: Awesome.

Charles Warren: (Unintelligible)

Charles Warren interview: Save the detective’s number

John Frawley: Awesome. Umm, you’ve actually helped me quite a bit. Uh, Charles, would you mind if I, if I have other questions could I call you? Would that be ok?

Charles Warren: Yeah, yeah.

John Frawley: Umm, it’s a lot to, to go through, as you can probably imagine.

Charles Warren: (Laughs)

John Frawley: (Laughs)

Charles Warren: Yeah I, let’s see here. Umm—

Willow Hendricks: Are you looking at—

Charles Warren: —I got to put his phone number in my—

Willow Hendricks: —save his number?

Charles Warren: —phone book.

Willow Hendricks: Save it so that you know who’s calling.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

Willow Hendricks: Yeah, that’s the other thing. Sometimes when we don’t know who’s calling we won’t answer it.

John Frawley: I don’t blame you.

Charles Warren: Well, it’s always these God damn salesmen. Yours is the 10-0, 1066?

John Frawley: Yeah, 1066. Yeah, I called your phone like you said and it said “this phone number’s no longer in service” and I remember you saying call it again so I tried it again.

Willow Hendricks: That’s when he was in the shower, so. I don’t usually answer his phone. He doesn’t answer mine.

John Frawley: When I heard you worked for the railroad, I thought you were like actually traveling from state to state on the railroad. But that’s not what you did?

Charles Warren: No, no, no.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: And your name is?

John Frawley: John.

Charles Warren: John, eh?

John Frawley: Yeah, you can call me John. John Frawley, is my last name.

Willow Hendricks: This is one time that I, like, ‘cause he’s just (unintelligible).

John Frawley: You want to grab it and do it for him. (Laughs)

Willow Hendricks: ‘Cause he, he never used to be like this. “How do I do this, how do I do that.” Then he’d get frustrated with it.

Charles Warren: Think I got it saved now.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: And I better put a ringtone on it.

Willow Hendricks: Just let it ring normal, honey.

Charles Warren: Well no, ‘cause it’ll indicate that it’s one of them guys calling, y’know.

John Frawley: (Laughs)

Willow Hendricks: He’ll be another 10 minutes now.

Charles Warren: (Unintelligible)

Willow Hendricks: (Laughs)

Charles Warren: Let’s see, you’ve got to find it in here.

Willow Hendricks: Yeah, he’s a real easy-going person, so.

John Frawley: Well I appreciate it.

Charles Warren: Make sure it saved it. It should be right there.

Willow Hendricks: Just go to your call logs.

Charles Warren: Huh?

Willow Hendricks: Right there.

Charles Warren: Oh, ok.

John Frawley: (Radio noise) 10-4, thanks.

Charles Warren: Ok. Let’s see. Let’s give you—

Willow Hendricks: Those phones down there, the phones there, the old radios they used at the railroad, the two-way radios.

John Frawley: Oh the, yeah, like this right here?

Willow Hendricks: Yeah.

John Frawley: Motorola?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

Willow Hendricks: Heck, they’re still doing that thing, too.

Charles Warren: Oh, they’re bigger than that.

Willow Hendricks: One’s about that size, the other two, they’re a little bit bigger. I thought that’s where we had the brick phones too but it’s not. I know I’ve seen ‘em down, probably in your other closet.

(Ringtone music plays)

Charles Warren interview: Picking up Sheree’s car

John Frawley: There we go. Alright Charles. So, so, but you didn’t take any, you didn’t take any time off from, from October to November. Is that what you’re saying, or do you remember that?

Charles Warren: Uh, I don’t remember taking any time off. Oh, I took some time off to go get the car.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: But you says that was how long after?

John Frawley: So, November 11th is when, is when I have the car being found.

Charles Warren: And it was some time after that. I don’t know exactly whether it was one or two days, uh, it seemed like I was in a hurry to get down there and get it, to get it out of impound.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: Umm.

John Frawley: But up until that time, were you still, you were still here though. Is that what you’re saying?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Did you travel at all? You didn’t travel at all?

Charles Warren: No, no. The only travel I made was to get the car.

John Frawley: ‘Kay. ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: Let’s see. That was ’85. Oh, y’know what?

Willow Hendricks: You don’t have (unintelligible)

Charles Warren: I eventually had to go to California.

Willow Hendricks: And that was later on that year.

Charles Warren: Yeah, it was later on.

Willow Hendricks: It was ’86, wasn’t it?

Charles Warren: Yeah, maybe it was ’86.

Willow Hendricks: I think it was beginning of ’86 you went to Roseville.

Charles Warren: I don’t remember.

John Frawley: What did you have to go to California for?

Charles Warren: Well, the (unintelligible) washed out and they laid us all off. And I had seniority as far as Sacramento—

John Frawley: Oh, ok.

Charles Warren: —so I just bumped that job down there and I actually had to work days on the ramp. I loved it. Yeah, umm, worked 10 to 6 with the weekends off. Couldn’t believe it.

Willow Hendricks: I almost want to say that was ’87 or ’88.

Charles Warren: I don’t know—

John Frawley: Would that’ve been, did you—

Charles Warren: —that was, that was that year. ‘Cause see I went to, what year did I, I went to Hawaii. Oh, I can’t remember what year I went to Hawaii.

Willow Hendricks: I think it was before.

Charles Warren: Yeah, oh it was, it was July. (Sighs)

John Frawley: Yeah, you’re—

Charles Warren: —it was June. ‘Cause Richard and I went camping at the end of May and somewhere around the 31st I flew to Hawaii with, uh, six other people. Well, five other people. There was six of us. And then—

Willow Hendricks: ‘Cause I seem to remember you telling me you were down in California for Christmas, or right after Christmas.

Charles Warren: —yeah, I can’t remember—

John Frawley: So, so Charles, did—

Charles Warren: —then after I come back—

John Frawley: —did you go to California between October and November of that year?

Charles Warren: I can’t remember.

John Frawley: Is it a possibility?

Charles Warren: Well, no because I was up here in October. I think I was still, I’m sure I was still working. Y’know, I just don’t remember how it worked out.

John Frawley: Could you have gone to California just before the car was reported found?

Charles Warren: It might’ve been that way, yeah. But anyway, I went to California to work.

Willow Hendricks: That was clear up in Sacramento.

Charles Warren: Yeah, Sacramento. And Alice was bringing the kids down to, to see me. And uh—

Willow Hendricks: (Unintelligible)

Charles Warren: —I traded the old Corolla in on a new Corolla. An ’86. Brand new ’86. I think that one was an ’84. And bought a brand new Corolla and she was driving that to bring the kids down to see me in Roseville and they, she crashed, wrecked it and she rolled it over about the, the police said about 10 times.

John Frawley: Oooh.

Charles Warren: Left the road at 70.

John Frawley: Alice did?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Was that in ’85?

Charles Warren: Yeah, well—

Willow Hendricks: I think that was ’86. I think you were down there in ’86, honey.

Charles Warren: —it may’ve been ’86. I don’t know, I don’t know. But it seems like it was right—

John Frawley: Well—

Charles Warren: —it had to’ve been when I had the new Corolla. Uh, it had to’ve been ’86 or ’85. It was towards the end of the year because, well, y’know—

John Frawley: It was after you got the Corolla back, is what you’re saying.

Charles Warren: Yeah, it was after that because I traded that Corolla in on a new ’86.

John Frawley: And I’m trying to, I’m just trying to lock in October and November, just right there. So you, you’re talking afterwards because you hadn’t even picked the Corolla up yet, right?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

Willow Hendricks: Yeah.

John Frawley: So—

Charles Warren: So, I probably went down, I’m just guessing, two or three days after I was told it was down there.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: Whatever the date was. I worked it out to go down there. I went down and, and got it and drove it back. I don’t remember how I got down there. Somebody’d have to drive me down there. Might’ve been Alice, I don’t know. Anyway, I went down and picked it up. I got it out of, and drove it home. And uh, drove for, ’round town for awhile to make sure everything was ok.

John Frawley: Ah.

Charles Warren: And uh, then I uh, I uh, took it down and traded it in.

John Frawley: That same, in ’85 you traded it?

Charles Warren: Yeah, ‘cause I bought, yeah ‘cause it’s sort at the end of the year. The ’86’s were out.

John Frawley: Oh ok.

Charles Warren: See, so I bought the ’86—

Willow Hendricks: He has to have, gettin’ a new car about every two years—

John Frawley: Ok.

Willow Hendricks: —if not every year.

Charles Warren: I used to do it every year, but. ‘Cause I was actually selling ‘em for Menlove Dodge Toyota. So I’d buy a Supra and sell that one to somebody and then buy another one.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: So—

Willow Hendricks: And he’s still that way.

Charles Warren: —now—

Willow Hendricks: —we’ve, we’ve gotten about every two years now.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Gotten back to every two?

Willow Hendricks: Can’t afford it as much anymore.

Charles Warren: But uh—

Charles Warren interview: A transaction in Elko

John Frawley: I did notice, umm, in the report there was, uh, you had a financial transaction in Elko, Nevada. In the, in the beginning of, of November.

Charles Warren: November in Elko?

John Frawley: And that’s why when you say you were going down to Sacramento, maybe that’s, is that a possibility?

Charles Warren: Financial transaction in Elko?

John Frawley: Elko, Nevada, yeah. Used your, your credit, your Visa card. Or your deb—whatever kind of card it was.

Charles Warren: Well, I drove back and forth between here and, uh, Roseville, uh, every two weeks.

Willow Hendricks: When you got transferred down there or when—

Charles Warren: Yeah, when I got transferred down there, when I bid down there. Or bumped down there, actually bumped down there. Umm, so I drove back and forth every two weeks because, uh, Alice was here with uh, George [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department]—

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: —and uh, she had her sister living with her, too.

John Frawley: Oh, ok.

Charles Warren: And her sister’s kid was a thief which, I really don’t know how much I lost because I didn’t care to look. But uh, I figured all my cell phones would’ve been gone and—

John Frawley: Oh.

Charles Warren: —and anything he could sell, uh, but anyway.

Willow Hendricks: But he’s trying to figure out would you’ve been in Elko the first of November.

Charles Warren: Yeah I would’ve, I would’ve been down there.

Willow Hendricks: Had you been transferred by then?

Charles Warren: Yeah, yeah. I was down there, sure. I was driving back and forth.

Willow Hendricks: But you didn’t pick up the car from Vegas until November 11th.

John Frawley: After the 11th. Couple, few days after.

Charles Warren: November 11th. Well yeah, but, I would’ve been down there, so I’d be driving back and forth in that Supra.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: Y’know, uh—

Willow Hendricks: But were you already down in Sacramento—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

Willow Hendricks: —at that time?

Charles Warren: —I was in Sacramento. I would’ve had to’ve been. ‘Cause I used all my vacation time and all my, uh, I had some other type of leave—

Willow Hendricks: But you were working in October?

Charles Warren: —whatever it’s called.

Willow Hendricks: You were working in October when she went missing?

Charles Warren: I can’t remember whether I was here.

Willow Hendricks: Did you maybe at that time go down to set up your trailer and your living situation with your uncle or whatever that was down there?

Charles Warren: No, no.

Willow Hendricks: Before you started working down there?

Charles Warren: Let’s see, I went down there. I, I took my dad’s trailer and uh, and put it in my uncle’s, or my cousin’s back yard. He had hooks up—

John Frawley: In Sacramento?

Charles Warren: —well, yeah. It’s actually in, uh, what’s the—

Willow Hendricks: It’s a suburb of Sacramento.

John Frawley: Roseville? You said Roseville.

Charles Warren: Well, it’s not even Roseville. It’s a—

John Frawley: Suburb.

Charles Warren: —suburb of that. Uh, actually but—

Willow Hendricks: He always refers to it as Roseville because that’s what the railroad refers to it as.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

Willow Hendricks: Just like Roper.

Charles Warren: That was a—

Willow Hendricks: It’s not Salt Lake, it’s Roper.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: But anyway, uh, I, when I got, when I got the job, I, when I bumped on the job I had to be there a certain date. So I took the truck and everything down a little bit ahead of time because all that time before, uh, I uh, was getting ready to, to go, see.

John Frawley: So, late October, early November you were, you were traveling between Utah and Sacramento to get set up down there.

Charles Warren: Uh, no. Like I say I can’t, I don’t think we, seemed like, God, I don’t know. I don’t know. Umm—

Charles Warren interview: Chuck’s railroad timecards

Willow Hendricks: Who’s one of the railroaders that worked with you at that time that would remember when—

Charles Warren: They’re all dead, honey. (Laughs)

Willow Hendricks: Want me to call (unintelligible) to see when it was?

Charles Warren: He wouldn’t know. He was a, he was not even working at that time. He uh, got fired or something.

John Frawley: Is there any way to go back and look at records from, from the railroad, or—

Charles Warren: Not that I know of, I don’t think they kept that, that old.

Willow Hendricks: But he’s retired now from it.

Charles Warren: Well, it was a different railroad. It was Southern Pacific. Sure Union Pacific didn’t keep any of their records. I wouldn’t think.

Willow Hendricks: How far back do your checkbooks go in the closet?

Charles Warren: Uh, I don’t know. I think just the ‘80s.

Willow Hendricks: (Laughs) That’s the time period honey. Want me to go look for a minute—

Charles Warren: No, no.

Willow Hendricks: —see if there’s anything?

Charles Warren: Well, this is what I know. I know that when I went, let’s see, seemed like Alice [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] everybody went with me in the truck when I went down there.

John Frawley: At the end of October?

Charles Warren: Might’ve been. I don’t know. I just can’t tell you.

John Frawley: Maybe I’ll, I guess Alice is the only other person I can ask.

Charles Warren: Yeah, that’s the, (pause) yeah.

Willow Hendricks: [Personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] remember that year.

Charles Warren: Let’s see if she’s around.

John Frawley: Oh, I can give her a call, Charles.

Willow Hendricks: ‘Cause you said you’ve talked to her before?

Charles Warren: She can probably help you figure it out.

John Frawley: Yeah, I did. I can talk to her again, Charles.

Charles Warren: Ok, well, you can figure it out. What we did (laughs) and, and what time she had the accident.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: Y’know, and uh, ‘cause I can’t even remember, I’m sure I got a new Corolla, ‘cause it was totaled out after the accident. And, but they were seat belted in so none of ‘em got hurt.

John Frawley: Oh boy, I’ll tell you what, that’s—

Charles Warren: But.

John Frawley: —that’s lucky.

Willow Hendricks: I seem to remember you telling me that was sometime, that you went down there, right around Christmas or the New Year. But I—

Charles Warren: I don’t, I don’t remember. Nevada was hot and dry because I, y’know, I come across there—

Willow Hendricks: Nevada’s always hot and dry. (Laughs)

Charles Warren: I drove really fast to get there and got, picked them up out of the Elko hospital. I do remember that.

John Frawley: You had to pick them up at—

Charles Warren: Alice and—

Willow Hendricks: After the accident.

Charles Warren: —after the accident, yeah. Picked them up out of the Elko hospital. I don’t remember what date that was.

John Frawley: (Radio noise) 10-4, thanks. So that would’ve been—(radio noise)—negative. Umm, so that would’ve been Elko, then—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: —hospital.

Charles Warren: I drove from Roseville to Elko, picked them up—

Willow Hendricks: When they had their accident.

Charles Warren: —yeah. And brought ‘em—

John Frawley: But you were already in California at that time?

Charles Warren: But I can’t even remember bringing them, whether I brought ‘em back to California with me or brought ‘em here. Must’ve, I’m pretty sure I brought ‘em, feels like I brought ‘em to California. But maybe.

John Frawley: I’ll give Alice a call—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: —and talk to her.

Charles Warren: She, she can probably remember better than I can.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: So, that’s the only think I can think.

Charles Warren interview: A friend in failing health

John Frawley: Ok. Alright, Charles. Well, I appreciate you talking with me. I don’t want to take your whole morning here. I know you’ve got to meet your friend there.

Charles Warren: Yeah.

Willow Hendricks: That’s all he’ll do is talk with him, so.

John Frawley: (Laughs)

Charles Warren: Yeah he’s dying [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department].

John Frawley: Oh, boy.

Willow Hendricks: Getting worse and worse.

Charles Warren: Yeah, I can barely understand him over the phone now. It’s only been, what, two weeks since I’ve seen him?

Willow Hendricks: Yeah, keep trying to—

John Frawley: Just degrade, just getting worse?

Willow Hendricks: —he keeps degrading, gets worse and worse.

Charles Warren: Goes fast.

John Frawley: Fast?

Charles Warren: Most people, most people [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department].

John Frawley: Wow.

Charles Warren: And he’s 65 or 6, 66 or 7.

John Frawley: Sorry. He beat the odds then, sounds like.

Charles Warren: Well, he really didn’t start getting it until, what, 6 to 8 months? Might’ve been a year ago it started hitting him where he started slurring speech like he had a stroke. And that’s what I thought he’d had ’til he finally told me it’s [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department]. Because his hands started deforming.

John Frawley: Oh.

Charles Warren: He’d lose all the muscles.

John Frawley: Uh huh.

Charles Warren: And eventually it, your muscle, heart muscle and all that kinda just, so that’s how it kills you. Just degenerates it, y’know.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: So, but it starts in the hands.

Willow Hendricks: I think he’s the only one that puts up with him so—

John Frawley: Ah.

Willow Hendricks: —he calls every other day almost, says “lets go get coffee.”

John Frawley: He needs, he needs somebody to talk to, probably.

Willow Hendricks: Yeah, he’s a good guy.

John Frawley: Hey Charles, is it ok if I come by and talk to you or call you again if I have any questions?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: Is that alright? I do appreciate your time and talking with me.

Charles Warren: Yeah, ‘cause I hope I can, y’know I just don’t remember, y’know. (Laughs)

Willow Hendricks: If you do remember something I’m sure you could call him, too.

John Frawley: Yeah, you have my card, or my number, so if something jogs loose and you’re like “whoa,” please call me and—

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: —and talk to me.

Charles Warren interview: More on Cary Hartmann’s psychic stories

Charles Warren: Well, I’m sure I told him everything. If he just wrote it down, y’know? Umm, then it should all be there—

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

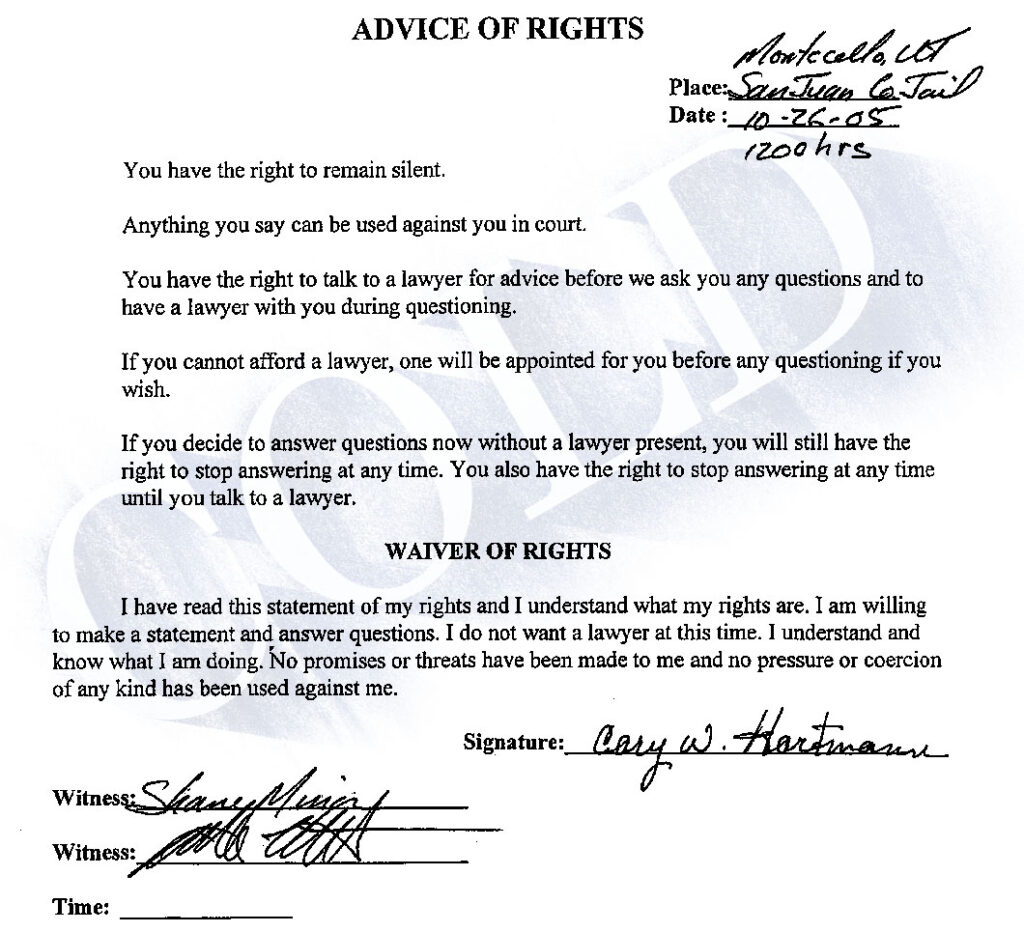

Charles Warren: —y’know, because, umm but, I don’t know. He may, I don’t know. ‘Cause I remember that something about Cary, uh, him or his buddy had a vision of something, y’know, about a pickup it seemed like. And then he told me, I remember him saying now that, uh, that, the pickup that this guy envisioned was Cary’s pickup, basically. And supposedly the guy that was driving that pickup did it. Whatever they did. So I don’t know. And that’s what he told me. I never got that from anybody else. And I can’t remember if he told, told me something else but I can’t remember what it was. It was about Cary. That was after they caught him and was trying to convict him. Or it might’ve been after they convicted him, I don’t know. But uh, but they, he said it was something like he was trying to confess to it (unintelligible) y’know, but I don’t know. Never worked out because him and another cop that worked there stayed friends with, I don’t know if he was an Ogden City cop or not—

John Frawley: Hartmann, or the friend?

Charles Warren: —uh, the, what was Cary’s name?

John Frawley: Hartmann, Cary Hartmann.

Charles Warren: Uh, and the friend was an Ogden City cop and they used to, he used to ride around with him after he, well, I guess before he went in prison. But they stayed good friends and I don’t know if they did after, I don’t know.

John Frawley: Hmm.

Charles Warren: They told me about, or Bell told me about him and this guy, him and this Ogden City cop, I’m pretty sure it was an Ogden City cop. I don’t think it was a Roy cop. But, anyway. I don’t know.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: I can’t remember. But so, if he didn’t write it down but I’m sure he probably didn’t now—

John Frawley: I’m not saying that, I’m just saying there’s a lot of, it’s, back then it was paper, y’know?

Charles Warren: Yeah.

John Frawley: And it’s, I’ve got to go through the paperwork. It’s not—

Willow Hendricks: Digitalized.

John Frawley: —it’s not all digitalized.

Willow Hendricks: They don’t have the cameras on the gas thing to say “yes, we can see you were here this day.”

John Frawley: Y’know, so I’m not saying that didn’t happen. I’m just—

Willow Hendricks: And it might be in Cary’s files instead of the Warren file.

Charles Warren: Well, y’know when, the thing about it is, I was driving, uh, back and forth every two weeks. Uh, from the time I got down to the Roseville area, uh, come home to, y’know, so whatever that was in Elko, I probably would’ve stopped there for gas. That was that waypoint, y’know? If you looked every two weeks you’d probably see a receipt there. Y’know? Uh, probably not at the same station but you would’ve seen it.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: And then once I got [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] stopped and we, uh, we didn’t live in the trailer very long because my dad come and got it to go down south to Phoenix with my mom and then we lived in a, or in a—

Willow Hendricks: Apartment.

Charles Warren: —apartment complex there. I almost remember the name of the town. Anyway, uh, yeah, uh, we lived in that apartment complex, uh, the first one I ever lived in and uh, we had a room on the bottom floor and it was, I think it was two bedrooms, so we had a bedroom and the kids had one and uh, that uh, that’s basically when we, she came down. Well, I know what it was. It was right after the accident. I must’ve brought them back with me and she went looking for (unintelligible). She’s the one that, she’s the one that got me to get this house and get an apartment, so, she went and got the apartment and—

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: —so, uh, but (sighs) I just don’t know.

Willow Hendricks: I don’t remember the time of year it was ‘cause—

Charles Warren: Nope.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Willow Hendricks: —Sacramento doesn’t have real seasons too much.

John Frawley: Right, it’s hard.

Charles Warren: Yeah, it’s like—

Willow Hendricks: A little bit, but not much.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: I wanted to stay down there, actually. But I didn’t, but uh, if I could’ve sold this house in that time, I probably would’ve ended up down there, ‘cause uh, it, it’s just the, I like the, the summer all year round—

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: —and the heat was, at 100, it’d get up to 106 every day down there. And 106 felt like 95 here. Y’know?

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: And uh—

John Frawley: I’ve got a brother living down there right now, in that area.

Charles Warren: Real dry, uh—

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: —real dry heat. But anyway, it felt like it. And matter of fact, when I came back here, this area was so much more humid I couldn’t believe it.

John Frawley: Huh.

Charles Warren: But we had the (unintelligible)—

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: —everything and uh, I remember that. I just felt terrible and I hated the lights. I run more red lights than—

John Frawley: (Laughs)

Willow Hendricks: (Unintelligible)

Charles Warren: I hated it. You’d be sitting there and nobody’s in sight you have to wait for a red light. In California you don’t do that.

John Frawley: You just go?

Charles Warren: Well no, in California the light’s always green for you if there’s no other cars on the road.

John Frawley: Oh, uh huh.

Charles Warren: It changes for you. That light system down there is 100 years ahead of ours up here.

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: 100 years ahead of ours as it is today, y’know. Geez.

Charles Warren interview: Sheree’s daily routine

John Frawley: Well you have helped me quite a bit, Charles, because it sounds like that day, I’ll try, I’m trying to figure out what her plan was that day. It sounds like her plan was, uh, leave work. You guys met in the morning, sounds like maybe you had time for coffee or something.

Charles Warren: Yeah. We usually had at least 30, 40 minutes before she left.

John Frawley: Umm, she was supposed to get you at Wagstaff Toyota but that didn’t happen. You were expecting her [personal information redacted by Roy City Police Department] and around 9:30 or 10 when that didn’t happen, you become concerned.

Charles Warren: Well she, she would always call me. Y’know?

John Frawley: And then you call Mary. Is that right?

Charles Warren: Yeah, I called her ‘cause (unintelligible).

John Frawley: Yeah.

Charles Warren: So, she want, it seemed like she wanted to get Adam that night and “well that’s ok, I’ll just hang onto him,” y’know? ‘Cause I had Alice there with me.

John Frawley: Let me ask you this, would Sheree’ve, do you, what would make Sheree deviate from that plan? ‘Cause it sounds like, was that more of a routine? It sounds like a routine.

Charles Warren: Yeah, it’s a routine we had every day.

John Frawley: That, that routine that I just explained is what you guys did every day?

Charles Warren: Right, except for that particular day, uh, I wasn’t working so she was just gonna come here and pick him up I would guess, I, but I just don’t know. I can’t remember talking to her about that.

John Frawley: ‘Kay. Alright, well, thank you.

Charles Warren: That was, that was a day I was off.

John Frawley: You were off that day?

Charles Warren: I was, or maybe I’d worked that night and got off that morning.

Willow Hendricks: You’re daytime.

John Frawley: So 12 to 8?

Charles Warren: Well yeah, 12 to 8 at working. So I would’ve got off—

John Frawley: Midnight to 8, or not, but you didn’t work ‘till 8, you’re saying. You’d leave—

Charles Warren: No, I’d go to work at midnight, get off at 8, meet her and then I’d wake up, I’d sleep, uh, if I could with the baby and I couldn’t then I’d sleep after I, after I dropped him off to her in the afternoon when she got Adam.

John Frawley: ‘Kay.

Charles Warren: But then I’d come back home and go to sleep until midnight.

John Frawley: Ok.

Charles Warren: So.

John Frawley: Alright Charles. Thank you, sir.

Charles Warren: Ok.

Willow Hendricks: I can get it.

John Frawley: Oh, you don’t have to get up. I’m going to get out of your hair. (Unrelated talk about cat furniture) Alright, well you have a nice day. And uh, I might call you with a question or two. Or stop by.

Charles Warren: Ok, sounds good.

John Frawley: Take care.

Hear where detective Frawley went next in Cold season 3, episode 9: A Picture in the Lobby

Episode credits

Research, writing and hosting: Dave Cawley

Audio production: Aaron Mason

Audio mixing: Ben Kuebrich

Cold main score composition: Michael Bahnmiller

Additional scoring: Allison Leyton-Brown

KSL executive producer: Sheryl Worsley

Workhouse Media executive producers: Paul Anderson, Nick Panella, Andrew Greenwood

Amazon Music and Wondery team: Morgan Jones, Candace Manriquez Wrenn, Clare Chambers, Lizzie Bassett, Kale Bittner, Alison Ver Meulen

Episode transcript: https://thecoldpodcast.com/season-3-transcript/a-picture-in-the-lobby-full-transcript/